Poems of Henry Louis Vivian Derozio

A Forgotten Anglo-Indian Poet

Introduction by F. B. Bradley-Birt

In all the fascinating pages of Anglo-Indian romance there is no more brilliant and pathetic figure than that of the boy-poet—Henry Louis Vivian Derozio. His brief career, so full of effort and enthusiasm, flashes like an inspiration across the dull grey story of his unhappy fellow-countrymen. Recognized at eighteen, even among the select little inner circle of intellectuals who then held sway in Calcutta, as a poet and writer of outstanding ability, he wielded an influence among his own contemporaries and over the younger students of his day, that, even allowing for the spell of his compelling personality, can only be regarded as amazing. To all with whom he came in contact he made the same magnetic appeal. Beneath the impulsiveness and vivacity and enjoyment of the boy there lay the depth and strength and broad-mindedness of the man, and it was this happy combination of the grave and gay, of the spontaneity of youth and the wisdom of age, that constituted something of the secret of his wonderful charm. Yet behind them both there lurked always the tragedy that his birth and genius entailed. It is the note of sadness that everywhere predominates, and as one reads his beautiful lines and impassioned words one feels the deep-rooted melancholy of the writer and the presentiment that he himself had of the inevitableness of his impending fate. In the midst of his strenuous work and youthful enthusiasm the end came to him in his twenty-third year.

There are few facts more pathetic and more deserving of sympathy than the mixed race which Western dominion in India has created and from which Derozio sprang. Closely allied by blood to European and Indian alike, the Eurasian community has fallen helplessly between them, failing to win acceptance from either of the great races that gave it birth. Looked at askance by both, it has been denied the advantages that its kinship to both would seem to have given it as its birthright. A modern race, with few inspiring traditions and no cohesion, it is small wonder that its claims, but timidly advocated, have been overlooked in the greater issues that have gone to the building up of our Indian Empire. Yet, undistinguished as its history as a race has been, it has not lacked its distinguished individual members, men and women, who have written their names on the long roll of Indian history and whose fame has spread even to the furthest limits of the West. Skinner of Skinner’s Horse, the famous Sikh Corps that still proudly bears his name, de Souza, the millionaire-philanthropist, James Kyd, the shipbuilder, Charles Pote, the artist, and John William Ricketts, the founder of Doveton College, are but a few of the best known names which any race might claim with pride, while among the fairer sex, Kitty Kirkpatrick, the admired of Carlyle, worthily represents the race’s traditional beauty, which, if it quickly fades, is of surpassing brilliance in the heyday of its youth.

In all its three centuries of existence Derozio is the only poet of real distinction whom the Anglo-Indian community has produced. The adverse conditions which throttled its vitality and ambitions were not such as to inspire the imagination or develop literary talent, while even the wrongs which it has so keenly felt have failed, save in this one instance, to find lyrical expression. Only for a few brief years Derozio voiced the sorrows and aspirations of his race in verse, taking into his youthful hands—he was not yet eighteen—the ‘Harp of India’ which had so long been silent, and whose music he awoke again to such wonderful effect.

Why hang’st thou lonely on yon withered bough?

Unstrung for ever, must thou there remain;

Thy music once was sweet—who hears it now?

Why doth the breeze sigh over thee in vain?

Silence hath bound thee with her fatal chain,

Neglected, mute, and desolate art thou,

Like ruined monument or desert plain:—

Oh! many a hand more worthy far than mine

Once thy harmonious chords to sweetness gave,

And many a wreath for them did Fame entwine

Of flowers still blooming on the minstrel’s grave:

Those hands are cold—but if thy notes divine

May be by mortal wakened once again,

Harp of my country, let me strike the strain!

There was nothing in the birth and ancestry of Derozio to foreshadow the brilliance of his brief career. The house in which he was born in Calcutta, on April the 18th, 1809, was pulled down some twenty years ago, its site being now occupied by a fine modern residence, number 155 Lower Circular Road, a little to the north of St. Theresa’s Church. Large and substantial, its possession by Francis Derozio, the poet’s father, affords proof that the family was at that time in circumstances of considerable affluence. Michael Derozio and ‘Bridget his lawful wife’ are the first of the name of whom trace remains. Michael is described, in St. John’s Baptismal Register of 1789, as ‘a native Protestant’, but a few years later in 1795 he is given in the Bengal Directory the more dignified appellation of a ‘A Portuguese Merchant and Agent’. That he was a merchant of position is proved by the fact that at one time, as the Bengal Records show, he proposed to purchase the whole of the Company’s opium—no small undertaking. James, his eldest son, like so many of his fellow-countrymen sought service with the East Indian Company, eventually becoming an Examiner in the Board of Revenue. Francis, his second son and father of the poet, was born in 1779 and married in 1806 a Miss Sophia Johnson, the sister of an indigo planter in Behar who was destined to be still more closely related to the Derozio family in after years. In this alliance of an Englishwoman and the son of a ‘Portuguese Merchant’ all the pathos of a mixed race was destined to be exemplified. Every one of their five children seems to have inherited the weakness of constitution that but too often descends as a legacy of mixed European and Indian parentage, not one of them living to attain the age of twenty-four years. Francis, the eldest, is reputed to have been the musical genius of the family, but little is known of him beyond the fact that he is believed to have died by his own hand at the age of twenty. Henry Louis Vivian was the second son. Claude, the third, was the only one of the family to be sent to Europe for his education, a rare advantage for an Anglo-Indian in those days. Five years younger than his brother Henry, it was to him that the poet at the age of sixteen addressed the lines, ‘To my brother in Scotland’, which, while they breathe a spirit of deep tenderness and brotherly affection, seem weighted with the fear of what the future might hold in store ‘for the fond, beloved boy’.

‘The uncertain future wakes the fear

I feel, but must not, dare not tell—’

The haunting fear that runs all through the poem was amply fulfilled. The brothers never met again, Claude being still in Scotland at the time of his brother’s death. It was not till five years later that he returned, only speedily to follow his brother to an early grave at the same age of twenty-two. Of the two sisters of the poet, Sophia died in 1827 at the age of seventeen, while Amelia, to whom her brother was so deeply devoted, died in 1835 aged twenty-two, having married her cousin Arthur Derozio Johnson two years previously. Thus of the five children of Francis and Sophia Derozio, three died at the age of twenty-two, while a fourth died before completing his twentieth year and the fifth when only seventeen. It was a tragic record, the mother herself having died nine years after her marriage.

Francis Derozio was employed in the mercantile firm of Messrs. James Scott and Co. and the esteem in which he was held is evinced by the fact that Mr. John Hunter, one of the partners, stood sponsor to his younger daughter, depositing as a christening present the sum of one thousand sicca rupees in the bank in her name. His son Henry, who was destined to bring such honour to his name, was baptised in St. John’s Church on August 12th, 1809, by the same chaplain, the Rev. James Ward, D.D., who less than three years later was to baptise at the same font a yet more famous infant—the future novelist, William Makepeace Thackeray.

Apart from the grief that the loss of wife and mother brought, it was a happy contented household that dwelt in the big square house in Lower Circular Road. Throughout his brief life this was the only home that the poet knew. His own bright lovable disposition early won him in the home circle the affection he was to gain so fully in a wider sphere in later life, and no cloud of bickering or ill-feeling seems to have crossed the horizon of these first childish days. In the year following his mother’s death his father married again, his second wife being a Miss Anna Maria Rivers, about whom little is known, but who is said to have been an Englishwoman of good family. If that be so, it would seem that there must have been something of his son’s charm in this son of ‘a native Protestant’ to have won the love of two Englishwomen. In her own advertisement in the India Gazette of 1831, published after the death of her husband and stepson, is to be found in language that reads somewhat quaintly at the present day almost all that is known of the second Mrs. Derozio. It is headed “Private tuition, Circular Road, Calcutta”. Below, the advertisement runs: “In consequence of the lamented and untimely death of her son Henry, Mrs. Derozio thus early publishes her intentions without delay. She purposes receiving under her roof a few young ladies and instructing them in the following branches:— English and French, Reading and Writing, Geography, History, Arithmetic, the Elements of Mathematic and Physical Science, Needlework and Domestic Economy. As Mrs. Derozio has enjoyed the benefit of the best education in England and as she will be assisted in the duties of teaching by a very competent individual, she hopes to afford every satisfaction to the parents and guardians of the children entrusted to her care. Being also anxious to give the female education a higher character than it has hitherto possessed in India, it will be her aim to realize that object to the best of her ability. Every possible attention will be paid to the health and morals of the young ladies, music, dancing, and drawing at the usual charges.”

Mrs. Derozio seems to have been a woman of tact and common sense and she completely succeeded in winning the affections of her stepchildren. She survived all the members of her household many years, dying in Calcutta in 1851.

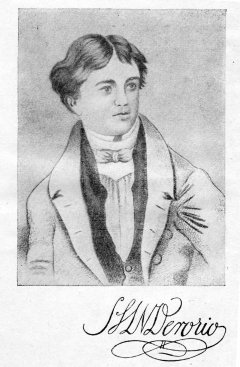

The year before his father’s second marriage, Derozio though only six years old had already begun his education at one of the most famous of private institutions in Calcutta, David Drummond’s Academy. For the next eight years he remained there, a wonderful understanding and friendship ripening between the honest plain-spoken Scotch dominie and the bright young lad in whom from the first moment that he took his place among his classmates the master recognized behind the childish intellect the touch of genius. Among his fellow-students and playfellows, as in later days amongst the intellectual society of Calcutta in which he moved, Derozio was always the leading spirit, throwing himself in those young days with wholehearted enjoyment into all a schoolboy’s joys and interests. His sympathetic smiling face, which the only existing portrait of him still presents, and his frank generous manners were an open sesame to all hearts. One who knew him well said he believed that Derozio never knew what ill-temper was. Only wrong-doing and injustice seemed to have the power to rouse his wrath. In the fullest measure from his earliest years he possessed that greatest of gifts that the gods bestow—the power of drawing all men to him in the bonds of friendship and affection.

II

The years during which Derozio was acquiring the rudiments of knowledge at Drummond’s Academy were a time of great intellectual awakening in Bengal. A famous centre of learning centuries before, the Province in these latter days had fallen a prey to political disturbances that left it little leisure for the calm pursuit of knowledge. The older days of Hindu patronage of learning had long since passed. Muhammedan authority in Bengal had from the first been too deeply engrossed in maintaining its hold over an unruly frontier province, its Viceroys too keenly bent on defying the Imperial power, to give much thought to the spread of general education which they themselves so little understood and so little valued. In the last decades of Muhammedan rule confusion had grown worse confounded and peace and progress seemed vain dreams. The Maharattas, formidable enemies of Islam, were thundering at its gates. Only the sudden rise to political power of the English Trading Company forestalled them.

Those first years of British rule are years of absorbing interest. Suddenly in the seventh decade of the eighteenth century there opened out a new and brighter era for Bengal. The first blessing that the distracted province craved was peace from active warfare; the second, a rule of law and order under which each man might go in security of life and property. There is nothing more remarkable, even in all the long and perplexing course of Indian history, than the speed with which these things were brought to pass. Where all was chaos and disorder, where the strong went armed and worked his will unchecked and the weak man went in fear and trembling, his life and property a prey to others, there suddenly arose at the command of a small commercial company from the west a marvellous network of administration, bringing peace and security and prosperity to the distracted land. The battle of Plassey, that great landmark in the story of Bengal, paved the way for these things in 1757. By the end of the century the English Company could look back upon a great work done. Into those few short years had been crowded a whole new chapter in Indian history. The little company that had so fearfully striven, in the midst of a lawless and disturbed province, merely to hold its own on the banks of the Hooghly as a private trading community had risen to supreme power, reducing the unruly to submission and imposing upon chaos the first principles of the rule of law and justice.

With the dawn of the new century internal peace and material prosperity opened the way to yet higher things. The influence of the west was slowly but surely finding its way into the innermost recesses of Bengal. In Calcutta, which in a century had grown from a cluster of native huts amidst the jungle to a fine and well-built city, the centre of Government and the headquarters of a busy trading company, western methods from the first had predominated. The city owed its very existence to the English Company. Here was no new civilisation imposed upon an ancient fabric. Rather here was a city of the west planted in the East clinging with pathetic persistence to western traditions and western methods, adapting itself only so far as the exigencies of climate and a six months’ voyage from the homeland necessitated. It was not so much the West planted in the East as the East gathering round the West, attracted by its success and eager to imitate its methods and adapt itself to its conditions.

The first training that the East had undergone at the hands of the West had been in business methods and the East had not failed to take advantage of it. With the rise of the Company to political supremacy still further opportunities opened out before it. The new system of administration required an army of subordinate officials and it was quickly realised that through Government service lay the surest road to place and power. The Hindu community, forced by necessity during long years of Muhammedan domination to adapt itself to circumstances, was the first to recognize the new order of things and to set itself to turn them to its own advantage. With ready perception it saw that a knowledge of English was the first essential to success and with praiseworthy energy and determination it set itself to acquire the strange language of its latest master. The Muhammedan community on the other hand, unaccustomed from long years of supremacy to adapt itself to new conditions, held for the most part aloof, with the result that it was hopelessly outdistanced, in the general progress that came to Bengal, by the race which it had so long ruled by force of arms.

With its final access to supreme authority and the subsequent settling down of the province, the real work of the East India Company had but begun. It was a task beset with difficulties. Deep-rooted racial prejudices stood everywhere in the pathway of reform. Yet with characteristic determination the Company set itself to the task, boldly facing even the unwelcome necessity of interfering with Hindu religious beliefs as in the abolition of Sati and the encouragement of medical science. Only the most recent and most difficult problem of all, arising out of its own success, it left unsolved. Hindus and Musalmans, who formed by far the larger portion of their new subjects, might present grave difficulties, but at least they were races long settled on the land with their own occupations, their own fixed places in the sphere of life. The English community, small and completely under the control of the Company which could still prevent the landing of an undesirable Englishman or tranship him back to England, offered no difficulties. But beside these three races there had begun to grow up another, a mixture of them all yet disowned of all. The Anglo-Indian problem is one of the heaviest legacies that British rule has left to India. For the most part the children of English fathers and Indian mothers, they occupied from the first moment of their existence as a race an anomalous position. The very circumstances of their birth placed them outside the pale. Into the rigid Hindu caste system it was impossible for them to enter even had they so desired. From the select little coterie of English officials among whom on social matters feminine influence reigned supreme, they were almost as rigidly excluded. Though many Anglo-Indian families traced their descent from legitimate marriages between Englishmen and Indians, the vast majority of them sprang from temporary alliances unrecognised by law and with no legal claim to the English blood which, nevertheless, gave them those deep-rooted instincts that prevented them from being absorbed in the native community and sharing its interests and occupations. The few exceptions to this general rule were mostly to be found among the children of Englishmen legally married to Indian wives who had consequently been brought up with the advantages of English home life and education. Among such families as these many distinguished names are to be found in the early part of the nineteenth century. But they were only a few of the more fortunate among the Anglo-Indian community. English in thought and upbringing, they were almost as far removed from the majority of Anglo-Indians as Englishmen themselves. And therein lay a further misfortune for the race. Families with only a small admixture of Indian blood and whose wealth of position placed them more or less within the ranks of the European community were for the most part eager to dissociate themselves as far as possible from their less fortunate fellow-countrymen. In their anxiety to hide their Indian blood and lay stress upon their European parentage they were entirely out of sympathy with their own race from which they desired so ardently to escape. The Anglo-Indian community was thus in the most unhappy position it is possible to conceive. Rejected by East and West it found itself promptly deserted by the majority of its own members who had in any way attained a position of eminence.

Unfortunate as its position was, however, the Anglo-Indian community had at the outset none but these intangible social disabilities to contend with. If they could only overcome the natural disadvantages of their birth and upbringing, practically every post in the Company’s service was open to them. They could aspire to enter and in fact did enter in considerable numbers all the Company’s services, civil and military. No actual or legal disability stood in their way until the year 1792. From that date onwards one career after another was closed to them. In the Gazette of June 1792 a notification was issued decreeing that no person, the son of a native, should henceforth be given any appointment in the civil, military or marine services of the Company. Three years later Anglo-Indians were excluded from admission to the European branch of the army in any capacity except as pipers, drummers, or bandsmen. Thus shut out from posts reserved henceforward exclusively for Europeans, they were equally debarred from other billets reserved exclusively for Indians, such as the prized and profitable appointments of Munsiffs and Sudder Ameens. Yet although Christians, almost without exception they were subject to the rule of Muhammedan law, save within the Presidency Town of Calcutta, and had neither the benefit of Habeas Corpus nor trial by jury. Under Regulation VIII of 1813 they were included as native subjects under the Company’s rule, thus suffering all the disadvantages imposed upon those who were not purely British. Moreover, though denied European advantages and forced to rank with Indians, they obtained none of the benefits conferred upon the latter in the way of education when the East Indian Company had leisure to turn its attention in that direction. Large grants were made towards the education of Indians, who also absorbed all the missionary effort which began to make itself felt in the early years of the nineteenth century. Practically no help at all was given to Anglo-Indians. Already labouring under heavy disabilities they were left almost entirely without part or lot in the general encouragement given to education. The result for them was disastrous, throwing them still further down the social scale. Indian youths, rapidly acquiring a knowledge of English and a considerable amount of general education, soon competed with them on their own ground and being able to accept clerkships on salaries on which it was impossible for an Anglo-Indian to live, they largely ousted them from the posts of which they had hitherto held the monopoly. As clerks in the big commercial offices and as ministerial officers in the Company’s service they had hitherto found posts eminently suited to their capacities. Now even these were taken from them by educated Indians on far smaller salaries. It seemed as if the last stronghold of the unfortunate Anglo-Indian community had been taken by assault.

Such was the position of his unhappy race, the knowledge of which was slowly borne in upon Derozio’s dawning intelligence as a youth in David Drummond’s school. There is small wonder that in his first songs written at the age of sixteen there is to be discerned that note of sadness from which his fettered spirit was never afterwards wholly able to escape.

My country! is thy day of glory past? A beauteous halo circled round thy brow, And worshipped as a deity thou wast— Where is that glory, where that reverence now? Thy eagle pinion is chained down at last, And grovelling in the lowly dust art thou: Thy minstrel hath no wreath to weave for thee Save the sad story of thy misery! Well—let me dive into the depths of time, And bring from out the ages that have rolled A few small garments of those wrecks sublime, Which human eye may never more behold: And let the guerdon of my labour be, My fallen country, one kind wish from thee!

III

During his eight years at Drummond’s Academy Derozio laid deep the foundations of his wonderful knowledge of English literature. It was a happy choice of his father’s that sent him for instruction to the zealous Scotch dominie. His was early marked out as one of the most promising among the many private schools that the sudden intellectual awakening in Bengal and the consequent demand for education had called into existence. Most of these private schools, whence emerged many of the distinguished men of the day, were set on foot by Anglo-Indians who seized upon this new profession as a godsend. In these schools Anglo-Indian and Indian students sat side by side, their interests for the moment identical—the eager pursuit of knowledge that should equip them in their struggle to keep pace with the rapid progress of the times. William Sherbourne, son of an Englishman and a Brahmin mother, was one of the first Anglo-Indians to take pride in his birth, and the school that he opened in a house in the Chitpore Road was long famous as one of the most successful seminaries of the day. Other well-known schools were Linstedt’s and Farrell’s, while Hutteman’s in Boitakhannah was famous for its classical learning and orthodoxy, ‘providing a sound educational training on traditional scholastic lines’. But of them all it was David Drummond’s school in Dhurrumtollah that counted the most distinguished roll. Drummond himself had come out from his home in Fifeshire with small prospects in 1813, obtaining as his first Indian billet an undermastership in a small school kept by Messrs. Wallace and Measures. From the first, however, it was obvious that he had found his calling and it was not long before he became sole proprietor of the school. Unfitted for an active life by a slight deformity, he threw himself heart and soul into the work of teaching, quickly proving himself a brilliant and original thinker, round whom gathered all the foremost intellectual leaders of the day. A classical scholar, a metaphysician, and a mathematician, he was the typical Scotch student of the early part of the nineteenth century, yet unlike most of his contemporaries he was not content with traditional learning but strove always after further and deeper knowledge. A man of strong individuality and keen intellect, his influence upon the youth of the day was immense. Calcutta, then only a small city compared with its later growth, offered a far narrower field in those days and personal influence was proportionately greater. Not only by his own force of character but still more through the youthful minds he imbued with his own enthusiasm he did much to encourage and direct the intellectual progress of his day. Like many other students Derozio was greatly indebted to his teaching.

From the first the classics had little attraction for Derozio in comparison with modern thought. Even in his early school days his knowledge of English literature was amazing. David Drummond encouraged theatrical performances among his boys as tests of memory and elocution, and Derozio was easily first amongst them all. “His very correct accent was extraordinary,” writes Dr. John Grant, Editor of the Examiner, quoting an original prologue that the youthful scholar of fourteen had recited “in a very becoming manner” at a prize-giving at Drummond’s Academy. On the same occasion Derozio received a medal with a descant on his merits ‘from his admiring master’. His popularity with both masters and schoolfellows is one of his most pleasing traits. David Drummond himself, the keen intellectual Scotchman not given to overmuch praise, wrote of him in the calm light of later days, seventeen years after the boy had left his charge as “the beloved of all who knew him”. There is a story that one day Derozio returned to school unexpectedly after a few weeks’ absence on account of illness and, the news of his return spreading into the classroom next to his own, where Drummond himself was lecturing, the youthful scholars rushed out, in spite of the awe-inspiring presence of the master, to welcome back their schoolfellow.

Among his playmates of those early years there were many who were destined to play distinguished parts in after life. Charles Pote, almost the only Anglo-Indian artist of distinction, whose fine picture of Lord Metcalfe is his best-known work, William Kirkpatrick, the kinsman of the famous “Kitty”, and Lawrence Augustus de Souza, whose name is destined to be for ever gratefully remembered for his kindly disposition of his wealth for the benefit of his community, were all Derozio’s early friends. Wale Byrne, the half-brother of Colonel John Byrne, C. B., Aide-de-camp to Lord William Bentinck and Lord Auckland, was a special friend of the boy-poet. With John William Ricketts, who so manfully supported the cause of the Anglo-Indian community before the British Parliament, he was destined to be still more closely associated in later days. There were many such who owed much to David Drummond’s teaching and example, but it was Derozio, their fellow scholar, with his brilliant intellect and deep earnestness, who fired their imaginations and inspired them with his own magnetic enthusiasm. Out of school hours he was still their leader, joining in all their boyish interests, swimming in the mornings in the Bamanbasti tank, playing cricket on the maidan in the afternoons, and passing the long winter evenings in rehearsing the plays for which their Academy was famous.

The circumstances that led his father to withdraw Derozio from school at the early age of fourteen are unknown. That there must have been some special reason for taking so promising a boy from his lessons at so immature an age seems obvious. It was, however, evidently his father’s first ambition that his son should follow in his own steps and join the same firm with which he himself had been so long and honourably connected. He had attained the responsible post of Chief Accountant and he doubtless looked forward to speedy promotion for his brilliant boy, under his own eye, in the same walk of life. So at the age of fourteen Derozio bade farewell to the school where he had spent eight happy years amidst congenial surroundings, and occupied an office stool in a mercantile office. It says much for his persistence and his respect for his father’s wishes that for two years he stuck to his uncongenial task, for if ever there was a youth whose inclinations and attainments unfitted him for the drudgery of office life it was Derozio. Full of life and energy, inspired with a passionate devotion to literature and the higher fields of thought, the daily tyranny of an office stool and the dull routine of clerical duties must have irked him almost beyond endurance. Even his father was forced at last to see that his son’s aptitude did not lie towards a business life, and a serious illness finally induced him to agree to his relinquishing it.

The next glimpse obtainable of Derozio reveals him in a new setting, in an indigo factory in Behar. It was to the house of his uncle, Mr. Arthur Johnson, at Bhagulpore, that his father sent him when the idea of a business career was finally abandoned. The uncle was an Englishman, born at Ringwood in Hampshire, who after some years in the navy had settled down at Bhagulpore at the then profitable profession of indigo-planting. He had married in 1810 Maria, the sister of Francis Derozio and aunt of the poet, and after her death in 1818 he had married her younger sister, Bridget. His own sister Sophia had married Francis Derozio in 1806, so that Arthur Johnson was three times over the uncle of the boy who was sent up to him to try his hand at indigo planting in 1825. Essentially a social being, eager to share his fellows’ joys and sorrows and already foremost among them, it might well have been imagined that the lonely factory would be almost as distasteful to him as the stool in a merchant’s office. The months he spent there, however, were destined to be of momentous import in his career. The solitude gave him time thoroughly to grasp and assimilate all that he had so rapidly learned and opportunity for deep and serious thought. Gradually as he grew to see things with greater clearness there came to him the revelation of his own exceptional gifts. In the midst of the primitive and picturesque scenes on the banks of the Ganges his gift of song first found expression and it was from the indigo factory, far removed from the surroundings to which he had always been accustomed, that he began to put forth those first literary efforts which were soon to attract the attention of all the leading intellects of his day in India.

The peaceful life of the up-country station made strong appeal to the town-bred boy. The common daily round of life as it had gone on in its changeless monotony for centuries was a new glimpse of human nature at its source to the youth who had been absorbed hitherto in his books. How vividly the smallest scenes and incidents appealed to him, the flood of poetry that from now onwards poured from his pen amply reveals. Here he was in touch with nature as he had never been before, and with nothing to distract his thoughts, he could watch with absorbing interest the whole ceaseless round of life in the changeless passing of the seasons—the ploughman urging his slow-moving bullocks through the rich, upturned soil: the sower going forth to sow, and the reaper gathering in his harvest: the happy nut-brown children, naked and unashamed, playing lazily in the dust and the sun: the housewife cooking her evening meal against her lord’s return or wending her way up from the river bank, her water-pot, filled to the brim, gracefully poised upon her head, her face averted beneath the close-drawn veil: the even rhythm of the oars upon the river: the cheerful throbbing of the drums: the sound of singing at the marriage feasts and the wailing of the women at the burning ghat—all these to the eager-minded boy were of abiding interest. To his poetic instincts they made instant appeal and his longest and most sustained effort, ‘The Fakir of Jungheera’, was directly prompted by these peaceful peasant scenes beside the Ganges. It was small wonder that the gigantic rock rising out of the midst of the river and towering over the low-lying alluvial plain with its air of mystery and romance impressed itself upon the boy’s quick imagination. “It struck me,” he wrote of it romantically, “as a place where achievements in love and war might well take place and the double character I had heard of the Fakir together with some acquaintance with the scenery induced me to form a tale upon both these circumstances.” Seventy feet it towers above the normal water level, its rocky formation in striking contrast with the sandy plain on either hand. So steep are its sides that only at one place can a boat put in. From there a precipitous and winding path leads to the summit which is crowned by a small hermitage, visited as a place of pilgrimage by wandering fakirs.

“Jungheera’s rocks are hoar and steep

And Ganges’ wave is broad and deep

And round that island rock the wave

Obsequious comes its feet to lave—

Those rocks, the stream’s victorious foes,

Frown darkly proud as on it flows,

Regardless of its haughty frown

The sacred wave flows hurrying down:

And fishers there their shallops guide

Upon the rosy-bosomed tide.

High on the hugest granite pile

Of that gray barren craggy isle,

A small rude hut, unsheltered, stands—

Erected by no earthly hands,

And never sinful foot might dare

To find its way unbidden there.”

It was from Bhagulpore that Derozio’s first efforts found their way into print. Dr. John Grant, the Editor of the India Gazette, quickly perceived the genius of the unknown young writer whose productions reached him from up-country, and from this time onwards dates the constant recurrence in the pages of his paper of the signature ‘Juvenis’, which the youth of sixteen with appropriate modesty adopted as his nom de plume. Dr. John Grant, who was destined to be the friend of his later years as David Drummond had been of his school-days, was a well-known figure in Calcutta and something of a character. “He was a man of great information and of infinite quotations,” wrote a contemporary, “could rap you out a paragraph of Cicero or half a page of Bolingbroke, simmered easily into poetry, and after dinner on his legs could pour you forth a stream of rhetoric which if it had had any religion in it would have done for a Scotch sermon.” Derozio’s brilliant and original style both in prose and verse was entirely after his own heart and so confident did he feel in the genius of his young contributor that he persuaded him not only to leave the indigo factory and come down to Calcutta, but to embark on that most venturesome undertaking for a budding poet—the publication of his verse in book form. In 1827, after two years amidst the peaceful country scenes on the bank of the Ganges which had done so much to foster his poetic genius, Derozio returned to Calcutta, definitely to embark upon a literary career.

With the publication of his first volume of verse, while still only in his eighteenth year, he suddenly found himself famous in the little world of Calcutta intellectual life. From the first moment of its appearance the success of the volume was assured. The extreme youth of the poet, his personal charm, and the promise of his verse, together with the fact that he was the first poet of a hitherto despised and ignored race, all combined to win for it immediate notice. The world of Calcutta was a small one, but for the moment a boy’s achievement was the talk of it. In spite of his youth his success gained him admittance into the little inner circle of keen intellects, both Indian and European, who were beginning to make their influence felt in society and politics. With all the keenness of his youth and enthusiasm Derozio seized the opportunities so suddenly and unexpectedly opened out to him. Into his literary work he threw himself with amazing activity. Appointed Assistant Editor of the India Gazette by his friend, the Editor, Dr. John Grant, he threw himself heart and soul into the congenial work.

Here at least his special talents had full play and he was soon not only doing the greater part of the editorial work of the Gazette but was seeking fresh scope for his activities. His contributions found their way into every paper in Calcutta, the Bengal Annual, the Calcutta Magazine, the Kaleidoscope, the Indian Magazine, and half a dozen other papers that sprang into existence on the wave of this new intellectual awakening that had come to Calcutta. A few months later, a youth still under twenty, he was starting a paper of his own, the Calcutta Gazette, with himself as editor and chief contributor.

But though a stream of literature in verse and prose, dealing with practically every topic of interest of the day, poured from his pen, it was inevitable that his eager sympathetic nature should seek a more personal outlet for its influence. The offer of an Assistant Mastership at the Hindu College, an unexpected honour for a youth not yet nineteen, came to him as a welcome opportunity, of which he enthusiastically availed himself. The Hindu College, founded in 1817 largely through the exertions of Ram Mohan Ray, Baidynath Mukerjee, Dwarka Nath Tagore, and David Hare, had already come to play a large part in the intellectual life of Calcutta and had won recognition from Government four years before. It was the first College, in the modern sense of the word, to be founded in India, and from its small beginnings may be traced the great network of educational institutions that now cover the length and breadth of the land. With its chief aim of imparting education on modern and western lines to the youth of India, Derozio was keenly in sympathy, and as Professor of English Literature and History he eagerly welcomed the opportunity of playing his part in the great work. His success was instantaneous. The power of his pen had already given him an influence out of all proportion to his years, but the power of his personal magnetism was to carry him still further. In less than two short years he succeeded in casting the glamour of his enthusiasm not only over his immediate pupils but over all that was best in the intellectual society of Calcutta. A born enthusiast, he possessed in full measure the gift of imparting that enthusiasm to others. His ready wit, his quick sympathy, his wide reading and originality of thought, and above all his personal magnetism riveted the attention of his pupils from the first, putting the acquisition of knowledge in a new light to their youthful minds as a pursuit of absorbing interest. How deeply he was devoted to them his lines addressed to the students of the Hindu College prove:—

“Expanding like the petals of young flowers

I watch the gentle opening of your minds,

And the sweet loosening of the spell that binds

Your intellectual energies and powers,

That stretch ‘like young birds in soft summer hours’ Their wings to try their strength. O, how the winds

Of circumstance, and freshening April showers

Of early knowledge, and unnumbered kinds

Of new perceptions shed their influence:

And how you worship truth’s omnipotence!

What joyance rains upon me, when I see

Fame in the mirror of futurity,

Weaving the chaplets you have yet to gain!

Ah! then I feel I have not lived in vain.”

Great, however, as his influence in the class-room soon became, Derozio realised that it was outside College hours, in the intimacy of their own homes or in his own, that his real opportunity lay. Round him in his father’s house in Lower Circular Road he gathered the most eager of his pupils, evening after evening discussing and debating, giving them of his best and drawing from them their best in return. The report of these informal gatherings soon went abroad and other than young college students were attracted to them. Such men as Captain Richardson, David Hare, and Oomacharan Bose eagerly welcomed this opportunity of friendly social intercourse which promised to raise a new intellectual bond of sympathy between the different races. So great became the desire for inclusion in them that Derozio determined to put them on a more formal and definite basis. The Academic Association thus evolved was one of the first associations of its kind in Bengal, its object being to form a common meeting-ground outside the restrictions of the class room where young men of whatever creed or caste might gather to discuss the multifarious topics that were absorbing the attention of the rising generation. In a garden house in Manicktolla the first meetings of the Association were held, Derozio’s wonderful gift of organization and inspiring enthusiasm making them an instantaneous success. Discussion ranged wide. Literature, art, philosophy, metaphysics practically every subject under the sun came under consideration. They were wonderful gatherings, these in the youthful days of the great city, a first tentative meeting of East and West, both for the first time united in the earnest search for truth. In the midst of the self-seeking and petty ambitions that so often mar the early struggles of those strenuous days, they come as a refreshing contrast of disinterested zeal and single-mindedness of purpose. The distinguished names in the social and official world of Calcutta, which appear among those who came to listen, testify to the widespread esteem in which Derozio was held. Derozio himself, young and brilliant, anxious only for the moral and intellectual progress of his boys and the improvement of his fellow-countrymen: Sir Edward Ryan, finding time in the midst of his heavy judicial duties to encourage by his presence these simple gatherings: Dr. Mill, Principal of Bishop’s College, mixing freely with his students out of College hours, respected and beloved: David Hare, the one-time watch-maker of Dundee turned educationalist, always sympathetic to youthful effort: Captain Byrne, A.D.C. to the Governor General, and Colonel Beatson afterwards Adjutant General, lending their social and official prestige, sat side by side in friendly converse and criticism with such men as Ram Mohan Roy, the great reformer and later the first orthodox Hindu to visit England, Mohes Chandra Ghose, one of the first converts to Christianity the year after Derozio’s death, Ram Gopal Ghose, part-founder in later days of the British India Association and the champion of his fellow-countrymen’s claims, Dakhinaranjan Mukharjee whose later adventurous career is worthy of a romance, and K. M. Bannerjee, a Kulin Brahmin of the highest caste yet later to become an ordained clergyman of the Church of England. And the life and soul of them all was Derozio, a youth not yet twenty.

It is difficult to realise such an influence in the Calcutta of to-day. Yet that it has not been exaggerated, not one but many contemporary writers bear witness. “Mr. Derozio’s disinterested zeal and devotion in bringing up the students in those subjects was unbounded, and characterized by a love and philanthropy which up to this day has not been equalled by any teacher either in or out of the school,” wrote Babu Hurro Mohan Chatterjee some years later. “The students in their turn loved him most tenderly and were ever ready to be guided by his counsels and imitate him in all their daily actions in life. In fact Mr. Derozio acquired such an ascendency over the minds of his pupils that they would not move even in their private concerns without his counsel and advice. On the other hand he fostered their taste in literature, taught the evil effects of idolatry and superstition: and so far formed their moral conceptions and feelings as to make them completely above the antiquated ideas and aspirations of the age. Such was the force of his instructions that the conduct of the students out of the college was most exemplary and gained them the applause of the outside world, not only in a literary and scientific point of view, but what was of still greater importance, they were all considered men of truth. Indeed the ‘College boy’ was a synonym for truth, and it was a general belief and saying among our countrymen, which those who remember the time must acknowledge, that ‘such a boy is incapable of falsehood, because he is a college boy.’”

This was the whole lesson of Derozio’s teaching. To pursue knowledge and seek diligently after truth must be the first aim of every serious student’s life and work. And for this purpose free discussion was essential. Criticism must range over the whole length and breadth and depth of human thought. In the meetings of the Academic Association there was no limit to debate. Beliefs that custom and superstition had held immune for centuries faded like mists before the rising sun in the light of knowledge and reason. It was inevitable that the rigidly orthodox should take fright. Vague rumours began to circulate among those who looked askance at this little company of earnest enquirers after truth, and it was not long before those who clung blindly to the accepted order of things saw that if the old beliefs were not to be seriously undermined, active measures must be taken. It was known among them that in these gatherings of brilliant students the Hindu religion with all its forms and ceremonies and superstitions was openly condemned, that female education was warmly advocated, and the practices of suttee vigorously denounced. Worse than this, orthodox Hindu students were ignoring caste distinctions, eating and drinking in common with their fellow-students of whatever religion or caste. Parents of an older generation, to whom the principles of modern western education were unknown, saw in Derozio’s teaching only its effect upon their religious beliefs, and, their religious antagonism once keenly aroused, they took strong measures to prevent the spread of what to them seemed only atheistical doctrines. The managers of the Hindu College, alarmed at the storm aroused and fearful of losing the students, many of whom their parents threatened to withdraw, were forced into a difficult position. On the one hand threatened with the loss of the prestige of the college, which they had laboured so hard to establish, they were certain on the other to be faced by a storm of criticism from the small but brilliant party of progress which controlled the press, if they attempted to check the flow of free thought and free discussion. In the interests of the College, however they considered that they were compelled to take action, though full well aware of the difficulties that beset them. Their first attempt only served to draw further attention to the matter. They issued a circular of mild expostulation. “The managers of the Anglo-Indian College, having heard that several of the students are in the habit of attending societies at which political and religious discussions are held, think it necessary to announce their strong disapprobation of the practice and to prohibit its continuance. Any students being present at such a society after the promulgation of this order will incur their serious displeasure.”

Even this mild expostulation roused a storm of criticism. It was recognized by both parties as the beginning of the battle and every newspaper in Calcutta devoted its leading columns to discussing it, all without exception condemning it in varying terms of opprobrium. “We regret much to see the names of such men as David Hare and Rosomoy Dutt attached to a document which presents an example of presumptuous tyrannical and absurd intermeddling with the right of private judgment on political and religious questions,” wrote one of the leading papers of the day. “The interference is presumptuous, for the managers, as managers, have no right whatever to dictate to the students of the institution how they shall dispose of their time out of college. It is tyrannical, for although they have not the right, they have the power, if they will bear the consequence, to inflict their serious displeasure on the disobedient. It is absurd and ridiculous, for if the students knew their rights and had the spirit to claim them, the managers would not venture to enforce their own order: and it would fall to the ground, an abortion of intolerance. We recommend the Managers to beware of pursuing the course they have begun. We are aware of their motives and if we saw any danger of the college passing under sectarian influence, we should be as stoutly opposed to such a result as we are to their present proceedings. But Christianity must not and shall not be put down by the means they are adopting. It must, at least, have a hearing from those who are willing to hear and this is all that its friends desire. They do not desire that any regulations should be made by the managers in favour of Christianity, but a Christian Government and a Christian community will not tolerate that the Managers of an Institution, supported in part by public money, should single out Christianity as the only religion against which they direct their official influence and authority. We hope that Messrs. Hill and Duff will revive the meetings if they have been discontinued and that their proceedings will henceforth be conducted on just and equal terms. We hope that the students of the Hindu College will continue to attend in spite of the prohibition and that the Managers will learn to keep within their own province, else they will have a storm about their ears which will be sooner raised than laid.” But it was a struggle of brilliancy and youth against wealth and influence and for a time at least it was evident that the latter held the upper hand. Twenty-five boys of the most respectable Hindu families were withdrawn from the College as a protest against the latitude allowed, while no fewer than a hundred and sixty were absent, reported sick, though it was obvious that they had been temporarily kept back from attending until it was seen what definite steps the Managers would take to restrict the college training merely to secular subjects, sternly repressing those unauthorised discussions on religious and philosophical subjects which had occasioned them so much alarm.

It is significant of Derozio’s extraordinary influence that there was never any question that it was this young teacher, then scarcely twenty years of age, who was the head and source of offence. The orthodox realized that if they could but secure his removal all would be well. He was the life and soul of this new spirit that so threatened their most cherished beliefs. Much as they misunderstood his methods of thought, they made no mistake as to his extraordinary power and influence over the minds of all those of a younger generation with whom he was brought in contact. Urged on from without, the managers of the college, realising the danger that beset their new and promising institution, met in solemn conclave to consider the situation. Among their number was Dewan Ram Comul Sen, one of those extraordinarily gifted men of that generation who rose from the smallest beginnings to great influence. Starting life as a compositor in a Mission Press on eight rupees a month, and ending by becoming famous as the author of the first English and Bengali dictionary and a member of every learned society in Calcutta, he was yet, in spite of his eager support of western education, found on the side opposed to Derozio. Not all his admiration of modern progress induced him to depart from the strictest orthodoxy. It was a curious triumph of the old over the new. While he did not fail to admire Derozio as one of the most brilliant products of western education, his strong underlying orthodoxy on religious matters rebelled against the younger man’s freedom of thought, and in their contest in Ram Comul Sen’s mind the latter instinct won the day. It was a momentous meeting for Derozio and it was obvious from the first that he had been judged unheard. One of the most orthodox among the managers proposed that Mr. Derozio, “being the root of all the evils and cause of public alarm, should be discharged from the college and all connection between him and the public cut off.” The discussion waxed keen, David Hare emphatically recording his opinion that “Mr. Derozio was a highly competent teacher” and that “his instructions have always been most beneficial.” Dr. H. H. Wilson, his firm friend throughout his career, also spoke strongly in his favour, but the majority of the managers was against him and his dismissal from his post, unheard, was decided upon. It was Dr. Wilson to whom fell the task of acquainting Derozio with this decision, though it appears from the latter’s reply that some opportunity of sending in what might read like a voluntary resignation had been offered him. Derozio, however, preferred to face the facts, declining to allow it to appear that he was giving up his work for any other reason except compulsion. The following was the simple and straightforward letter he wrote in reply to Dr. Wilson’s letter:

Calcutta, 25th April, 1831.

Dr. H. H. Wilson.

My dear Sir,—

The accompanying is my resignation, but you will observe that I have taken the liberty of departing from your suggestion of making it appear a merit on my part. If I had grounds to believe that my continued connection with the College could be really and permanently prejudicial to that institution, the spirit to leave it, without any suggestion but that of my own mind, would not be wanting. I do not conceive, however, that a temporary shock needs such a sacrifice: and I cannot, therefore, conceal from myself the fact, that my resignation is compulsory. Under these circumstances, I trust you will see the propriety of my declining to make that appear a merit which is really a necessity. Nevertheless, I thank you heartily for having recommended me to do so, because I perceive it to be the dictate of a generous heart anxious to soothe what it could not heal. But I dare not ascribe to myself a merit which I do not possess; and if my dismissal be considered a deserved disgrace by the wise and good, I must endure it.

As the intemperate spirit displayed against me by the Native Managers of the College is not likely to subside so completely as to admit of my return to that institution as speedily as you expect; and as the chances of life may shape my future destiny so as to bring me but rarely in contact with you, I cannot permit this opportunity to pass without recording my grateful acknowledgments to you for all the kindness you have shown me since I have had the honour and pleasure of being known to you. In particular, I must thank you for the delicacy with which you conveyed to me, on Saturday last, the resolution of the Managing Committee and for the sympathy which I perceive my case has excited in you.

Such circumstances, when genuine and unaffected, make deeper impressions on my feelings than those greater acts of favour, the motives for which we cannot always trace.

Believe me to be, my dear Sir, with sentiments of respect and regard,

Yours sincerely,

H. L. Derozio.

Derozio's formal letter of resignation which accompanied the letter to his friend is written in the same simple straightforward style, studiously moderate and not unmindful of the kindness he had received.

To

The Managing Committee of the Hindu College.

Gentlemen,

Having been informed that the result of your deliberation in close committee on Saturday last was a resolution to dispense with my further services at the College, I am induced to place my resignation in your hands, in order to save myself from the mortification of receiving formal notice of my dismissal.

It would, however, be unjust to my reputation, which I value, were I to abstain from recording in this communication certain facts which I presume do not appear upon the face of your proceedings. Firstly, no charge was brought against me. Secondly, if any accusation was brought forward, I was not informed of it. Thirdly, I was not called up to face my accusers, if any such appeared. Fourthly, no witness was examined on either side. Fifthly, my conduct and character underwent scrutiny and no opportunity was afforded me of defending either. Sixthly, while a majority did not, as I have learned, consider me an unfit person to be connected with the College, it was resolved, notwithstanding, that I should be removed from it, so that, unbiased, unexamined, and unheard, you resolve to dismiss me without even the mockery of a trial. These are facts. I offer not a word of comment.

I must also avail myself of this opportunity of recording my thanks to Mr. Wilson, Mr. Hare, and Baboo Sreekissen Sing for the part which, I am informed, they respectively took in your proceedings on Saturday last.

I am, Gentlemen,

Your obedient servant,H. L. V. Derozio.

Dr. Wilson’s reply, with its unexpected questions relating to the specific charges brought against Derozio, shows the writer’s friendliness and sympathy, and elicited from Derozio, who had never even been informed as to what the charges against him were, an indignant denial and a dignified confession of faith. Dr. Wilson wrote:—

25th April, 1831

Dear Derozio,

I believe you are right: although I could have wished you had been less severe upon the native Managers, whose decision was founded merely upon the expediency of yielding to popular clamour, the justice of which it was not incumbent on them to investigate. There was no trial intended—there was no condemnation. An impression had gone abroad to your disadvantage, the effects of which would not have been dispelled by any proof you could have produced, that it was unfounded. I suppose there will still be much discussion on the subject, privately only I trust, but that there will be; and I should like to have the power of speaking confidently on three charges brought against you. Of course, it rests entirely with you to answer my questions. Do you believe in a God? Do you think respect and obedience to parents no part of moral duty? Do you think the intermarriage of brothers and sisters innocent and allowable? Have you ever maintained these doctrines by argument in the hearing of our scholars? Now I have no right to interrogate you on these or any other of your sentiments, but these are the rumoured charges against you, and I should be very happy if I could say boldly they are false; or could produce your written and unqualified denial for the satisfaction of those whose good opinion is worth having.

Yours sincerely,

H. H. Wilson.

At last Derozio was face to face with the ridiculous charges that his enemies had brought against him and he was able to put in his defence. He wrote on the following day

26th April, 1821.

H. H. Wilson, Esq.,

My dear Sir,—Your letter, which I received last evening, should have been answered earlier but for the interference of other matters which required my attention. I beg your acceptance of this apology for the delay, and thank you for the interest which your communication proves that you continue to take in me. I am sorry, however, that the questions you have put to me will impose upon you the disagreeable necessity of reading this long justification of my conduct and opinions. But I must congratulate myself that this opportunity is afforded me of addressing so influential and distinguished an individual as yourself upon matter which if true, might seriously affect my character. My friends need not, however, be under any apprehension for me: for myself the consciousness of right is my safeguard and my consolation.

(1) I have never denied the existence of a God in the hearing of any human being. If it be wrong to speak at all upon such a subject, I am guilty, but I am neither afraid, nor ashamed to confess having stated the doubts of philosophers upon this head, because I have also stated the solution of these doubts. Is it forbidden anywhere to argue upon such a question? If so it must be equally wrong to adduce an argument upon either side. Or is it consistent with an enlightened notion of truth to wed ourselves to only one view of so important a subject, resolving to close our eyes and ears against all impressions that oppose themselves to it?

How is any opinion to be strengthened but by completely comprehending the objections that are offered to it, and exposing their futility? And what have I done more than this? Entrusted as I was for some time with the education of youth peculiarly circumstanced, was it for me to have made them pert and ignorant dogmatists, by permitting them to know what could be said upon only one side of grave questions? Setting aside the narrowness of mind which such a course might have evinced, it would have been injurious to the mental energies and acquirements of the young men themselves. And (whatever may be said to the contrary), I can vindicate my procedure by quoting no less orthodox authority than Lord Bacon:— “If a man,” says this philosopher (and no one ever had a better right to pronounce an opinion upon such matters than Lord Bacon), “will begin with certainties he shall end in doubt.” This, I need scarcely observe, is always the case with contented ignorance when it is roused too late to thought. One doubt suggests another, and universal scepticism is the consequence. I therefore thought it my duty to acquaint several of the College students with the substance of Hume’s celebrated dialogue between Cleanthes and Philo, in which the most subtle and refined arguments against Theism are adduced. But I have also furnished them with Dr. Reid’s and Dugald Stewart’s more acute replies to Hume,—replies which to this day continue unrefuted. This is the head and front of my offending. If the religious opinions of the students have become unhinged in consequence of the course I have pursued, the fault is not mine. To produce convictions was not within my power: and if I am to be condemned for the Atheism of some, let me receive credit for the Theism of others. Believe me, my dear Sir, I am too thoroughly imbued with a deep sense of human ignorance, and of the perpetual vicissitudes of opinion, to speak with confidence even of the most unimportant matters. Doubt and uncertainty besiege us too closely to admit the boldness of dogmatism to enter an enquiring mind: and far be it from me to say “this is” and “that is not”, when after the most extensive acquaintance with the researches of science, and after the most daring flights of genius, we must confess with sorrow and disappointment that humility becomes the highest wisdom, for the highest wisdom assures man of his ignorance.

(II) Your next question is, “Do you think respect and obedience to parents no part of moral duty?” For the first time in my life did I learn from your letter that I am charged with inculcating so hideous, so unnatural, so abominable a principle. The authors of such infamous fabrications are too degraded for my contempt. Had my father been alive, he would have repelled the slander by telling my calumniators that a son who had endeavoured to discharge every filial duty as I have done, could never have entertained such a sentiment; but my mother can testify how utterly inconsistent it is with my conduct, and upon her testimony I might risk my vindication. However, I will not stop there: so far from having ever maintained or taught such an opinion, I have always insisted upon respect and obedience to parents. I have indeed condemned that feigned respect which some children evince, as being hypocritical and injurious to the moral character: but I have always endeavoured to cherish the sentient feelings of the heart, and to direct them into proper channels. Instances, however in which I have insisted upon respect and obedience to parents, are not wanting. I shall quote two important ones for your satisfaction: and as the parties are always at hand, you may at any time substantiate what I say. About two or three months ago Dakhinarunjun Mookerjee (who has made so great a noise lately) informed me that his father’s treatment of him had become utterly insupportable, and that his only chance of escaping it was by leaving his father’s home. Although I was aware of the truth of what he had said, I dissuaded him from taking such a course, telling him that much should be endured from a parent, and that the world would not justify his conduct if he left his home without being actually turned out of it. He took my advice, though I regret to say only for a short time. A few weeks ago he left his father’s house, and to my great surprise engaged another in my neighbourhood. After he had completed his arrangements with his landlord, he informed me for the first time of what he had done: and when I asked him why he had not consulted me before he took such a step:— “because,” replied he, “I knew you would have prevented it.”

The other instance relates to Mohesh Chunder Sing. Having recently behaved rudely to his father and offended some of his other relatives, he called upon me at my house with his uncle Umacharun Bose and his cousin Nondolal Sing. I reproached him severely for his contumacious behaviour, and told him that, until he sought forgiveness from his father, I would not speak to him. I might mention other cases, but these may suffice.

(III) “Do you think marriages of brothers and sisters innocent and allowable?” This is your third question. “No,” is my distinct reply; and I never taught such an absurdity. But I am at a loss to find out how such misrepresentations as those to which I have been exposed have become current. No person who has ever heard me speak upon such subjects could have circulated these untruths: at least, I can hardly bring myself to think that one of the College students with whom I have been connected could be either such a fool as to mistake everything I ever said, or such a knave, as wilfully to mis-state my opinions. I am rather disposed to believe that weak people who are determined upon being alarmed, finding nothing to be frightened at, have imputed these follies to me. That I should be called a sceptic and an infidel is not surprising, as these names are always given to persons who think for themselves in religion: but I assure you, that the imputations which you say are alleged against me, I have learned for the first time from your letter, never having dreamed that sentiments so opposed to my own could have been ascribed to me. I must trust, therefore, to your generosity to give the most unqualified contradiction to these ridiculous stories. I am not a greater monster than most people, though I certainly should not know myself were I to credit all that is said of me. I am aware that for some weeks some busybodies have been manufacturing the most absured and groundless stories about me, and even about my family.

Some fools went so far as to say my sister, while others said my daughter, (though I have not one), was to have been married to a Hindu youug man. I traced the report to a person called Brindabone Ghosal, a poor Brahmin, who lives by going from house to house to entertain the inmates with the news of the day, which he invariably invents. However, it is a satisfaction to reflect that scandal, though often noisy, is not everlasting.

Now that I have replied to your questions, allow me to ask you, my dear Sir, whether the expediency of yielding to popular clamour can be offered in justification of the measures adopted by the Native Managers of the College towards me? Their proceedings certainly do not record any condemnation of me, but does it not look very like condemnation of a man’s conduct and character to dismiss him from office when popular clamour is against him? Vague reports and unfounded rumours went abroad concerning me; the Native Managers confirm them by acting towards me as they have done. Excuse my saying it, but I believe there was a determination on their part to get rid of me, not to satisfy popular clamour, but their own bigotry. Had my religion and morals been investigated by them, they could have had no grounds to proceed against me. They therefore thought it most expedient to make no enquiry, but with anger and precipitation to remove me from the institution. The slovenly manner in which they have done so, is a sufficient indication of the spirit by which they were moved: for in their rage they have forgotten what was due even to common decency. Every person who has heard of the way in which they have acted is indignant; but to complain of their injustice would be paying them a greater compliment than they deserve.

In concluding this letter allow me to apologise for its inordinate length, and to repeat my thanks for all that you have done for me in the unpleasant affair by which it has been occasioned.

I remain, etc.,

H. L. V. Derozio.

Deeply as Derozio felt the manner of his leaving his work in the Hindu College, there was some compensation in the greater freedom his independence gave him. In journalism he found a wider outlet for his energy and a larger audience to bring under the spell of his influence than as a teacher among his class of boys. He little foresaw when he plunged with youthful energy into journalism in the spring of 1831 that scarce eight months more of life remained to him. Though the same spirit of harmony still reigned, a change had fallen over the home circle in Lower Circular Road. Derozio’s father had died and the circumstances of the family were no longer as affluent as they had been in earlier days. His now widowed step-mother, whom if she had been his own mother he could not have regarded with deeper affection, and his sister Amelia, to whom he was devotedly attached, were now almost entirely dependent upon him and he settled down to what he believed would prove his life’s work with hope and confidence. Whatever lack of sympathy and injustice he had met with in the world without, he had never from the first experienced anything but perfect happiness in his home life and this to one of his sensitive, sympathetic nature was no mean cause for gratitude.

His first literary venture after his return to journalism was the production of The East Indian, the first newspaper to be devoted especially to the cause of the Anglo-Indian community. How ably it was run, Dr. John Grant testifies. There could be no difference of opinion, he wrote, as to “the talents, the perfect honesty and the unfettered views of the Editor.” Besides running his own paper he found time to contribute to almost all of the many other papers that the keen intellectual revival of the day had produced, The India Gazette, The Calcutta Literary Gazette, The Indian Magazine, The Calcutta Magazine, The Bengal Journal, The Enquirer and The Hesperus.

Derozio’s last act was to take part in the annual examination of the pupils of the Parental Academy, afterwards the Doveton College. On December 17th The East Indian gives a report of the Examination from Derozio’s pen, in all probability the last lines that he was destined to write. They are in the same fine large-hearted spirit that had breathed through all his brief but brilliant career. “The most pleasing feature in this institution is its freedom from illiberality,” he wrote. “At some of the Calcutta schools objections are made to natives, not so much on the part of the masters as of the Christian parents. At the Dhurrumtolla Academy it is quite delightful to witness the exertions of Hindu and Christian youths, striving together for academic honours. This will do much towards softening asperities which always arise in hostile sects: and when the Hindu and the Christian have learned from mutual intercourse how much there is to be admired in the human character, without reference to differences of opinion in religious matters, shall we be brought nearer than we now are to that happy condition when

‘Man to man the world o’er,

Shall brothers be and a ‘ that.’

“To those parents who object to the bringing up of their children among native youths, we desire to represent the suicidal nature of their conduct. Can they check the progress of knowledge at certain schools? Can they close the gates of the Hindu College, and other institutions? If not, is it not obvious that they cannot withhold knowledge from Hindu youths and if they manifest illiberal feeling towards those youths, are they not afraid of a reaction? In a few years the Hindus will take their stand by the best and the proudest Christians and it cannot be desirable to excite the feelings of the former against the latter. The East Indians complain of suffering from proscriptions, is it for them to proscribe? Suffering should teach us not to make others suffer. Is it to produce different effects on East Indians? We hope not. They will find after all, that it is their best interest to unite and co-operate with the other native inhabitants of India. Any other course will subject them to greater opposition than they have at present. Can they afford to make more enemies?”

These are fine last words. They were written with no inkling, as he penned them, that they were the last he was ever to give to the world. They breathe so true a spirit of large-mindedness and tolerance, and at the same time so accurately forecast coming events that it is with an effort one recalls to memory the writer's youth. The promise of spring was still upon him, for there wanted yet four months to the completion of his twenty-third year. In this enlightened warm-hearted boy lay the hopes of his fellow-countrymen. What might not his genius and enthusiasm have done for his neglected race? In him at last it had produced the brilliant advocate it had so long awaited. But it had produced only to lose. In his early death there is written the tragedy of his race. The inexorable law that its beauty quickly fades, seemed inevitably to apply to this exceptional beauty of soul. The qualities of the race were there, but not yet were they to find full expression and recognition.

The end came suddenly. It was the fell disease that lays low with such appalling suddenness, against which even the strongest constitution is of no avail. There had been much sickness that rainy season and cholera had done even more than its usual share in filling the graveyards of Calcutta, and keeping the burning ghats along the Hooghly always smouldering. Even when the rains had passed, it still lingered and in those days the unfortunate victim who once fell a prey to the disease seldom recovered. On Saturday, December 17th, the very day on which his last note appeared in The East Indian, Derozio was stricken down. At first it was hoped that it was only a mild attack and that his youth and buoyant spirit would bear the strain. For six days he fought manfully for life, racked with pain and delirious with fever, yet always thoughtful for those about him, the step-mother and the sister he loved, and the friends and pupils who had hung upon his words in days gone by and who now gathered round his bedside, realising in awe-stricken silence that they were watching the passing of him they loved. He died on the 26th of December 1831, in his twenty-third year.

It is impossible to say to what heights Derozio might not have risen had his life been spared. His writings are extraordinarily mature, considering his years, and his poems show a remarkable command of language and beauty of expression: and if, in spite of their unbounded enthusiasm, their wealth of imagery, and their passionate resentment of wrong, they lack something in originality and undoubtedly owe much to Byron and Moore, his contemporaries, it must be remembered that death at the age of twenty-three cut short the undoubted promise his youthful work evinces. It is difficult to believe that one who showed such early promise would have failed to attain to greater things with maturer years. Yet it may be that his was the brief spark of genius that flashes but for a moment—a spark too brilliant for the frail body that encases it and that by its very effulgence works its own extinction. There can be no doubt from his poems that his was one of those natures not made for happiness. He lived life too intensely, his sympathies were too widespread, his sensitive mind too much alive to the eternal sadness of things, for him ever to lead the ordinary life of his fellow-men.

“Good night! Well then, good night to thee,

In peace thine eyelids close;

May dreams of future happiness

Illume thy soft repose.I’ve that within that knows no rest,

Sleep comes to me in vain:

My dreams are dark —I never more

Shall pass ‘good night’ again.”

So it may be that death was a happy release to the ardent spirit that must always have chafed against the limits of this mortal life. He himself had written of ‘Death my best friend’, and he doubtless realised that only in another life could he attain the full knowledge and the full truth which he so diligently sought.

“Death my best friend, if thou dost ope the door,

The gloomy entrance to a sunnier world,

It boots not when my being’s scene is furled,

So thou canst aught like vanished bliss restore.

I vainly call on thee, for fate the more

Her bolts hurls down, as she has ever hurled;