Kabul to Kandahar

To the Abiding Memory of

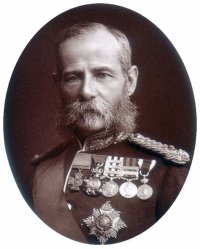

Field-Marshal

Earl Roberts of Kandahar

V.C., K.G., K.P., G.C.B, etc.

and to His Daughter

The Countess Roberts of Kandahar,

I Dedicate This Book

His life was gentle; and the elements

So mixed in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world — ‘This was a man.’

—Julius Caesar

Author’s Note

I have refrained from loading this brief record with footnotes and references: but all details are exact, even to spoken words—so far as history can be exact.

The last hours of the Guides, in Kabul Residency, can only be known from hearsay, but I have relied mainly on The Story of the Guides by Colonel George Younghusband, C.B. (Queen’s Own Corps of Guides) since the writer must have heard all that could be known.

To readers unfamiliar with India’s frontier policy, the following epitome statement may help to make my allusions clear.

The ‘forward’ policy in its widest sense—at the time I write of—implied active control of Afghan affairs, and the sphere of British influence extended right up to the Oxus. The ‘backward’ school—headed by John Lawrence—saw the Indus as India’s natural boundary; and aimed at a ‘closed frontier’ beyond it, even as regards the whole tribal area. Fight them when necessary: otherwise, let them be. Between these two extremes, a later school favoured a boundary known as the ‘scientific frontier’, outlined by Sir Mortimer Durand; British roads, railways, and influence covering the whole tribal area, and aiming at a friendly alliance with Afghanistan, avoiding active intervention or invasion. In fact, the ‘forward’ policy, in its moderate form, is the recognized Frontier policy to-day.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Guide to Pronouncing Indian and Afghan Names

a = u in ‘but’

ā = ar

i = ee

ir = eer

e = ai in ‘rain’

in = een

ai = as i in ‘vine’

ō = as o in ‘note’

u = oo

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Prelude

The story of the Second Afghan War is compounded of ingredients all too familiar in British annals. It is a story of political adventure and misadventure, redeemed by soldierly achievement; of a war reckoned unjust by some, inevitable by others; of a small, fierce independent state wedged between two great acquisitive powers: the eternal Asiatic triangle of Russia, England and Afghanistan.

Since the days of Peter the Great, Russia has aimed at capturing Indian trade, at destroying England’s ruling power in Asia; an aim never fulfilled, yet never abandoned to this day.

When the time was ripe for Russia’s rapid strides across Asia, England’s long trading period in India had passed into a period of war and expansion, that began with Clive and lasted till the time of the Mutiny. By then, she had annexed the Punjab and the Borderland beyond the Indus; while Russia had pushed her Eastern boundary to the frontier of North Afghanistan.

That lawless, fanatical country, always at war with itself, had become—as it was to remain—the traditional corn of wheat between two grindstones: Russia, a dreaded neighbour, England, a would-be ally, whose friendly advances might cloak possessive designs. Its three main provinces—Kabul, Kandahar and Herāt—had been ruled by rival chiefs all steeped in treachery, murder and intrigue, till there rose one man strong enough to weld them into a united Kingdom.

Handsome and virile, a just but iron-handed ruler, Dōst Mahomed Khan was known among his people as the Amir-i-Kabir—the Great Amir. First he conquered his weaker brother, Shah Shujah, who fled to British India for protection; then he pulled his faction-ridden kingdom together and won the allegiance of its quarrelsome chiefs. To establish his power, to check Russo-Persian designs on Herāt and Kandahar through a working alliance with Great Britain—such was his sane and politic ambition. Through England’s Agent, Alexander Burnes, he made it clear that he preferred British friendship to Russian promises. But it so happened that a new Viceroy had lately arrived in Simla: the cool and cautious Lord Auckland, chosen by the Whigs as ‘a safe man’. Like all new Viceroys, he depended, for counsel, on the Simla Foreign Office and a ‘forward’ group of secretaries, for whom ‘the Great Game’ in Central Asia had become an obsession.

To Dōst Mahomed’s genuine bid for friendship he turned a sceptical ear. He would promise nothing. He demanded all. And because Dōst Mahomed would not bind himself unconditionally to so lop-sided an alliance, he was written down ‘a hostile chief, harbouring schemes of aggrandisement injurious to the security and peace of India’s frontier’—which then lay south of the Punjab! And that was but the prelude. The safe man, unsafely led, called into being the ill-fated ‘Army of the Indus’; drove Dōst Mahomed from his throne and proceeded to force upon the Afghan people Shah Shujah, the Undesired—a mere pawn in the ‘Great Game’.

From one unprovoked act of injustice sprang disaster on disaster; loss of valuable lives, money and prestige; the massacre of a British army, and the murder of Shah Shujah by his own subjects: a chapter of tragedies, muddles and heroism unequalled in British annals. Followed the crowning irony: a deported Amir solemnly returned to his throne by those who had driven him from it three years earlier; while Russia, unperturbed by the upheaval, bided her time.

But British generosity covers many sins. The Dōst, in banishment, had a handsome pension and a fine house in Calcutta. He had seen British power broad-based on just government: had borne himself throughout with a kingly dignity and absence of rancour. Only at sight of his capital, half destroyed by Pollock’s avenging army—hatred inevitably flared up for a time; and another ten years were to pass before he achieved the alliance he had pleaded for in 1837.

Those ten years saw Russia paramount in Central Asia; England established in the Punjab—ably ruled by John Lawrence, the strong man of his day, who set his face like a rock against any more costly and disastrous Afghan adventures. But in the Sixties Russia swept on again with gigantic strides: Tashkent, Bokhara, Khokund, Kiva in vain resisted her onset. By ’76 her eastern boundary had reached the outlying Afghan provinces, while India’s policy was still governed by the ‘ backward ‘ school, who saw the Indus as her natural frontier. John Lawrence had been wise in his day; but even the wisest policy must change with changing times. His creed of masterly inactivity could not check the rising tide of Russian activity; and in the Seventies British India awoke to renewed concern for the fate of Afghanistan, no longer held together by the strong hand of its Amir-i-Kabir.

His successor, Sher Ali, resembled him only in a sincere desire to maintain British friendship and follow British counsel. Lord Lawrence—returned to India as Viceroy—had been good to him. Lord Mayo had helped him with a subsidy; and after Mayo came Lord Northbrook, a man of the ‘backward’ school, averse from any intervention—friendly or otherwise—in Afghan affairs. To him Sher Ali had appealed for the revision of a certain agreement between Russia and the British Foreign Office; but he had firmly refused to intervene, or even to promise armed help in case of a Russian attack. He had refused to recognize Sher Ali’s favourite younger son as heir to the throne. So, in treacherous Afghan fashion, the Amir had seized and imprisoned his true heir, Yakub Khan, and kept him in durance for six years. Rebuffed by the English, he had turned his back on them—like Dōst Mahomed twenty years earlier—and lent a willing ear to the overtures of Russia.

To India, meantime, the swing of the party pendulum had brought a Viceroy of the opposite school, armed with clear instructions to check the designs of Russia and establish closer relations with Afghanistan. In the face of Lord Northbrook’s final despatch—urging the wisdom of non-interference, the unwisdom of forcing a British Envoy on Kabul undesired by the Amir—Lord Salisbury bade Lord Lytton lose no time in despatching an envoy to Kabul, ‘charged with the task of overcoming the Amir’s apparent reluctance’, and announcing the arrival of a new Viceroy anxious to cultivate closer relations with himself and his kingdom.

So, in April 1876, Lord Lytton landed in Bombay, resolved to abolish the ‘closed frontier’, to establish British influence and control from the Khyber to the Oxus. To achieve these great ends and inaugurate a new Indian era, the man and the hour seemed aptly met together.

For, by the middle Seventies, British dominion in India was at its apex of stability and power. Through the two great periods of trade and expansion, it had passed to the crowning period of Empire and internal progress. It had lived down the shock of the Afghan disaster, the critical strain of the Mutiny. From the hills to the sea there was peace and prosperity, light taxation, little or no internal trouble. The Civil Service was at its zenith of power and prestige. A fine army—British and Indian—kept order within the frontier and could be trusted to repel any attempt at invasion. Only beyond the Himalayas loomed the oncoming menace of Russia. Whether or no that menace was over-coloured by apostles of the ‘forward’ school, Lord Lytton had his orders, plus his own personal conviction. Accordingly he wrote to Sher Ali proposing a British Agent at Kabul for consultation and advice. But the friendly gesture that would once have been welcome had come too late. The Amir—still smarting from his failure with Lord Northbrook—suspected, not unnaturally, that the new Viceroy was more concerned to safeguard British interests than his own. His tardy answer, polite but discouraging, vexed Lord Lytton and moved him to warn the Amir that by refusing to see a British Envoy he would alienate a friendly power; one that could pour an army into his country before a single Russian soldier could reach Kabul. Round a friendly Amir that army could form a defensive ring of iron; an unfriendly one it could ‘break as a reed’.

The veiled threat sprang from Lord Lytton’s not unfounded belief that Afghan Amirs were less likely to be influenced by offers of help than by fear of British power to hurt them. Coming in the teeth of fresh overtures from Russia, it must have given Sher Ali furiously to think. For six weeks he left the Viceroy’s letter unanswered. Then he wrote briefly, ignoring the proposed mission, offering to send his own Native Agent to Simla that there he might ‘learn the things concealed in the generous heart of the English Government’. And if a hint of irony lurked in that last, it was not altogether without reason.

Lord Lytton agreed to receive the Nawab, gave him a courteous hearing, and a list of concessions that would be signed on given conditions. He would recognize Sher Ali’s chosen heir, Abdulla Jan; grant him an increased yearly subsidy, and lend him British officers to train his army. But—the Amir, in return, must break with Russia; must accept British Agents at Kabul, Herāt and elsewhere, encourage trade with India and give Englishmen the free run of his country. A treaty on these lines he proposed to confirm by a personal meeting; and the Amir was graciously invited to attend the Imperial Delhi Assemblage on New Year’s Day, 1877, when Queen Victoria would be proclaimed Empress of India before all the chiefs of her realm.

To these unwelcome proposals Sher Ali vouchsafed no answer till the ‘tumult and the shouting’ had subsided. Then he wrote, offering to send his most trusted Minister for discussion of the treaty with Sir Lewis Pelly at Peshawar; and there the two men met in an amicable spirit that could not charm away the fundamental opposition of their principals. Their talk resulted in a deadlock. Nor were matters improved by the Afghan Minister’s untimely illness and death at Peshawar.

When news of the double disaster—death and failure—reached Kabul, it so mortified Sher Ali that he flew into one of his violent rages, flung invectives at the perfidious infidels, who would never come to terms with him. If they desired war, they should have it. He would raise the whole country against them; every rupee in his Treasury he would hurl at their accursed heads.

So ran the report. True or untrue, the fact remained that Viceroy, Amir and Russian Generals had, between them, sown the dragons’ teeth presently to spring up as armed men—precursors of a second Afghan War.

Phase I

1

In June 1878, Simla was electrified by news of Russian regiments mobilized on the Oxus, a Russian Envoy welcomed at Kabul, as Imperial Ambassador, received in state by Sher Ali and his most powerful Sirdars. The Amir, without warning, had struck a shrewd blow at British pride; but more than pride was involved at that critical moment. For Russia was still at war with Turkey. Five thousand Indian troops had been sent to Malta lest England might feel bound to intervene. And here was Russia’s ‘retort courteous’: regiments on the Oxus and an Ambassador at Kabul. The double challenge left England no alternative but a forward move to find out what was really happening in that far country, where no Russian rival could be allowed to gain a dangerous foot-hold. So Lord Lytton, with the full consent of Whitehall, insisted on the immediate like reception of a British Mission: arrangements to be made with the leading Sirdars for its safe conduct to Kabul.

The move—though aimed at Russia—imposed a hard problem on the Amir. With a rebellious son and a discontented people, with two great countries pressing their claims on him, he might well feel like an earthen vessel between two iron pots. And it so happened that Lord Lytton’s unwelcome letter coincided with the death of his favourite son, Abdulla Jan. Personal grief and public mourning provided excuse for delaying a difficult answer, while the Man on the Spot hinted at the awkwardness of jointly entertaining the Agents of two rival powers who were potentially at war.

That argument decided a perplexed Amir against receiving the British Mission. But he still sent no word to India, where all was being arranged for an immediate advance through the Khyber Pass, under General Sir Neville Chamberlain and his chief Political Officer, Major Pierre Louis Napoleon Cavagnari, C.S.I.: a notable personality, half French, half Irish, pleasant-mannered, bearded, with the air of a scholar rather than a soldier, and twenty years of distinguished Border Service behind him. His experience in seven Frontier campaigns, had won him a reputation for handling the Pathan tribes with a blend of firmness and courtesy backed by unfailing personal courage: fine qualities off-set by a mind fatally prone to see men and things as he would have them be; to let desire override judgment and personal ambition over-ride all.

Such was the man chosen to pilot Lord Lytton’s uninvited Mission through the formidable Khyber, monarch among passes, and through a possibly inimical Afghanistan.

On September the 21st the whole party—two hundred troops and a dozen British officers—marched out from Peshawar and encamped at Jamrud, near the mouth of the Pass. Sir Neville, doubtful of their welcome, sent forward Cavagnari, with Colonel Jenkins of the Guides Corps and a small escort, to interview the General commanding Fort Ali Musjid, and arrange for a peaceful passage through the Khyber. Within sight of Ali Musjid, he was checked by information that Afghan levies barred the Pass. If they advanced they would be fired on.

Cavagnari answered coolly that they would continue to advance till they were fired on; and his resolute tone took effect.

A meeting was arranged beside the stream that flows beneath the fort-crowned mass of rock: Cavagnari, with Jenkins, a few Guides and native gentlemen; Faiz Mahomed with a following of some sixty troops. And while they talked, fresh Afghans kept casually strolling up, till the little group was enclosed in a wall of armed men.

The General, courteous but unbending, stated his sovereign’s orders: a British Mission could not be allowed to pass unchallenged through the Khyber. In vain Cavagnari argued that they came on a peaceful errand, to confer with The Amir in a spirit of friendship.

The word roused Faiz Mahomed to sudden anger.

‘Friendship? Wah-illah! Who knows the heart of the British Government? Your people come here without invitation; bribing the Amir’s servants to give them passage; setting Afridi against Afridi—and calling themselves our friends . . . !”

An uneasy murmur from the crowd warned Cavagnari not to risk brave men’s lives in further vain argument.

‘Discussion is useless,’ he said sauvely. ‘We are both Government servants acting under orders. I ask only one question—If the Mission advances, will you oppose it with force?’

And Faiz Mahomed answered straightly, ‘With all the force at my command. It is only because of former friendship that I do not shoot you all now for what your Government has done already’.

On that amicable declaration of war, they shook hands: the advanced guard of the Mission rode back to Jamrud—rebuffed.

Whether or no a deliberate insult had been intended was a question that only Sher Ali could answer: and insult or no, the Jamrud episode sealed his doom. In Lord Lytton’s view he had forfeited all claim to further friendly advances.

While a formal demand for explanation and apology sped to Kabul, troops were massed for a triple advance through the Khyber, the Kuram Valley and the Quetta route to Kandahar. That demand, couched in ‘hard words’, was not calculated to promote peace; and when at last the Amir replied, he offered no apology, expressed no desire for improved relations. So deeply had the iron of distrust entered into him, that he believed these unfathomable British desired no friendship, would accept no apology. And Lord Lytton—receiving neither—promptly launched his ultimatum, allowing a further period of grace, at the insistence of Lord Salisbury. But Sher Ali remained silent and sullen in his threatened capital, heart-broken by the death of Abdulla Jan, and obliged, in consequence, to reinstate his true heir. Convinced that those aggressive English clearly meant to fight, he may have dreamed, Afghan-like, of luring them into his difficult country and overwhelming them, as before.

In any case, the 20th brought no reply: and on the 21st—after thirty-seven years of ‘masterly inactivity’—a British army entered Afghanistan. On the 30th a letter dated 19th, vague and evasive in tone, reached the Khyber General—ten days too late. The march of events had foreclosed on the hapless Amir.

Lord Lytton, from his own standpoint, had played his cards well. Most Englishmen, at home and in India, honestly believed Sher Ali to be faithless and foresworn, secretly in league with Russia. And as proof to that effect was not lacking, the few men who believed otherwise spoke to deaf ears. Undeniably the threat of Russia paramount at Kabul involved a very real menace to India; though both Lord Lytton and Cavagnari underrated the Afghan as a fighter, and the probable length of the war. This was their hour. The word had gone forth. Sir Donald Stewart’s force was on its way to Kandahar. General Sir Sam Browne, V.C., had already captured Ali Musjid; and the Kuram Field Force was preparing to clear Afghan troops from the rugged range that closes Kuram Valley like a wall.

That stubborn task had been entrusted to a leader of proven courage and daring—Major Frederick Roberts, R.A., V.C., C.B.—destined to win new laurels in Afghanistan; to become, in later years, the universally beloved soldier, whom England and India delighted to honour.

A small, compact man, of untiring energy, with keen blue eyes and a resolute chin between his Balaclava whiskers; with a natural gift for initiative and swift decisions, an Irish readiness to face risks, and to justify them by invincible courage in the hour of emergency: such was the ‘Bobs’ of Kipling’s tribute—

‘He has eyes all down his coat,

And a bugle in his throat;

And you will not play the goat—

Under Bobs.’

A strict disciplinarian, he spared neither himself nor his men; and he could get the last ounce out of them by reason of his own example, his unfailing consideration for them, and that indefinable essence of leadership—personality. By a brave exploit in the Mutiny he had won the Victoria Cross; and on appointment to his first full command in the field, he was given the local rank of Major-General.

It was a moment of proud, if anxious responsibility, knowing—as he did—-that his troops were too few, his transport woefully insufficient, even for those few. Easy enough for Lord Lytton, in Viceregal Lodge, to hug the fond belief that the mere threat of three approaching British Armies would suffice to overawe and subdue Sher Ali. It needed faith of quite another quality to face—ill-equipped yet undismayed—the rugged bulk of Peiwar Mountain, bristling with guns and regular Afghan troops, unlikely to be overawed by the threat of so small an invading force, however boldly led.

The Pass itself crossed a precipitous ridge two thousand feet above the valley: a position of such immense natural strength that, in the face of it, Roberts admitted—to himself alone—‘a feeling akin to despair.’ For none knew better than he that his numbers were ‘terribly inadequate for the work to be done.’ Yet done it must be.

In that resolute spirit he designed a plan for the only feasible form of attack—a turning movement, that would involve the capture of a lesser hill to the right of the Afghan position, coupled with a feint of attacking elsewhere. Not even his own troops—except commanding officers—must guess his true intent: everything hung on secrecy and surprise.

In the freezing dark of a December night his few picked regiments crept soundlessly out of camp, tents left standing, watch-fires burning: only five guns and a thousand men left for defence and the feint attack. If the small force—which he was using like a finely tempered sword—were broken against this rocky barrier, he had no other weapon for retrieving disaster. Whatever the odds, he must not fail.

Up and up they trailed, that thin line of troops and baggage animals, through a great ravine, narrowing to the rocky bed of a mountain stream. As the towering cliffs closed in on them, the bitter cold intensified and darkness deepened, till a waning moon looked over the edge, silvering one cliff wall, but throwing into denser shadow the mere track they must follow: men and animals splashing through the stream, scrambling and stumbling over rocky boulders coated with ice; incessant halting to let the rear close up, though all hung on reaching the foot of the pass before dawn.

Roberts, anxious and impatient, rode forward to speed up the van, led by the 29th Punjab Infantry, a regiment of high repute; but the Pathan companies might possibly prove restive at the prospect of killing fellow-Moslems. He found them marching in very casual order; and even as he questioned the Colonel, two shots rang out. Colonel Gordon’s Sikh orderly whispered, ‘Hazúr, there is treachery among the Pathans.’

It was a moment of acute anxiety. Those signal shots might wreck everything. Loth to discredit a fine regiment, or risk further delay to find out who had fired, Roberts could only change the order of the march and press on—hoping for the luck that seldom failed him at need.

As the east lightened, they reached the foot of the pass; and were greeted by a hail of bullets from above.

At a given order, the Gurkhas fixed bayonets and charged up the rocky slope, Highlanders and a Mountain Battery in support. Gallantly they rushed the first entrenchment; another and another: and Spin Gawai Kotal was won.

But ahead of them still loomed the stubborn bulk of the Peiwar. After their bitter night march, they must face a stiffer ascent through a dense pine forest—every rock or lurking shadow a possible enemy; over felled trees and masses of rock, now creeping, now climbing; urged on by the impatience of their General, he and his staff giving them a lead. In two hours they gained the summit—to be daunted by the discovery that no supposed ridge linked one kotal to the other. At their feet the ground fell away steeply. Across the chasm rose a densely wooded hill, alive with unseen Afghans: and the crackle of Enfield rifles laughed them to scorn. Worse: the vanguard, urged on by Roberts, had lost touch with the main body of troops. In the wood behind them, not a sign of Gurkhas, Highlanders or guns. Confused by the dense undergrowth they must have taken a wrong direction; and there, on jaded horses, sat Roberts and his staff, alone with the unreliable 29th Punjab Infantry, exposed to a galling fire from unknown enemy numbers, not a hundred and fifty yards off.

Danger so grave and immediate might well shake the stoutest nerve; but it was precisely such moments of crisis that revealed the full measure of Roberts as a soldier and a man. A forward move looked impossible; yet his indomitable spirit saved him from a fatal move backward that would have drawn the Afghans after him, and sealed the fate of his small scattered force. If there had been some error in over-haste, it was finely atoned for now. One after another he sent his staff officers to seek the missing troops, hoping that the sound of firing might guide them aright. None returned; and none were now left but the Reverend J. Adams, a soldierly parson, who had begged to go with him as A.D.G. Adams, too, was sent off on the fruitless quest; while Roberts, with imperturbable sang-froid, showed as bold a front to the bewildered enemy as though he had an army corps behind him instead of one infantry regiment, half of it possibly ripe for mutiny. Unexpected inaction encouraged the Afghans. Every moment their firing increased. Even a vain forward move were better than none—could the unreliable 29th be urged by a personal appeal to wipe out the slur cast on their loyalty.

A vain hope. Response came only from the Sikhs; and their Captain told Roberts privately that the Moslems would not fight.

Even that ill news failed to shake his nerve. With such men as he could trust, the forward move must at least be attempted. It was a gallant venture against impossible odds; for his men were too few, the Afghans too strong in numbers and position. Back they must clamber to their exposed hill-top, harassed by a jubilant enemy; the General’s devoted orderlies—two Sikhs, two Pathans, two Gurkhas—valiantly protecting him throughout, resolved that no bullet should touch him if one of them could intervene. Baulked, but not cast down, they returned to find their missing comrades pouring out of the wood—Gurkhas, Highlanders and guns.

But numbers alone could not solve the main problem. Its solution arrived opportunely in the person of an officer from General Palmer’s cooperating force. From him Roberts learnt how that smaller force had worked round the far side of Peiwar Kotal and up through a narrow defile; how one of their officers had caught a distant glimpse of the whole Afghan camp; soldiers, followers and animals asleep in fancied security; had seen a hill-top, whence a few shells might be dropped among them with telling effect.

Decisive action at last. In no time two mountain guns were dropping shell after shell into that crowded mass of men and animals, spreading confusion and dismay. Tents caught fire. Terrified mules, camels and drivers bolted helter-skelter, causing a scare that soon infected all ranks. Gunfire slackened; the infantry broke and fled. Roberts, through his telescope, watched them scurrying away down the road to Ali Khel—and knew he had achieved his end.

His own troops held the Spin Gawai Kotal; Palmer’s troops held the Peiwar. That satisfying certainty must suffice till next morning: since he could neither cut off the Afghan retreat, nor force on his willing men till they had been refreshed by food and sleep. As it was—for precaution’s sake—they must drop into a deep nullah, cross a frozen stream and push up on to higher ground. There, on the bitter hillside, nine thousand feet above the sea, they slept under the stars, without even coats to cover them; impervious, through utter weariness, to hunger, hard lying and twenty degrees of frost.

Roberts himself slept as soundly as on a feather bed. His hazardous action had been crowned with victory. A position deemed impregnable had been gained; several regiments of the Afghan army routed, and eighteen guns with large stores of amunition captured: an achievement for which he gave full credit to his troops, while they in turn gave honour where it was due. One who fought his first battle that day, wrote afterwards: ‘From the start, General Roberts inspired all under his command with supreme confidence in his judgment as a General, in his boldness as an intrepid leader.’1 And to a leader who has won the full confidence of his troops all things are possible.

He had dispersed—as bidden—all Afghan garrisons south of the Shutar Gurdan Pass; and their achievement chimed in with successes elsewhere. Sir Sam Browne had pushed on to Jalalabad. Sir Donald Stewart, early in January, occupied Kandahar. By then the last of the Russians had long since vanished from Kabul. Sher Ali—deserted by one Great Power, threatened by another—had released his true heir and decided on flight from three victorious British columns preparing to sweep the country almost unopposed.

To Sir Sam Browne he had sent word that he was leaving Kabul for St Petersburg to lay his case before the Czar. But at the outsetting of that vast journey he was ignominiously checked by the Governor of Tashkent, who turned him back from the Russian frontier. Ill and brokenhearted, he remained in Afghan-Turkistan, whence he wrote to his former friends: ‘If any harm shall now befall Afghanistan, the dust of the blame will settle on his Imperial Majesty’s Government.’ But Imperial officials—thick coated already with ‘dust of blame’—were troubled not at all by the curse of a dying Amir.

For the end was at hand. Sher Ali, self-dethroned, made no effort to recover his shattered health. He refused food and medicine, refused to let doctors remove his mortified leg. What mattered a diseased limb, compared with news from Kabul that the British armies had been everywhere held up by natural difficulties. A part of Stewart’s force, aiming at Herāt, had been checked on the Helmund river. Browne, for lack of carriage, never left Jalālabad.

Roberts’ troops—after the dashing Peiwar victory—remained encamped in the Kuram, their numbers daily thinned by disease. No sign anywhere of that swift advance on Kabul. And for Sher Ali—ill-happed by fate and his own failings—there remained only death.

In February, 1879, the son who had no cause to mourn him, informed Lord Lytton that his honoured father had ‘cast off the dress of existence, obeyed the voice of the Summoner, and hastened to the region of Divine Mercy.’

His death and the accession of Yakub Khan—who had no quarrel with England—brought the brief first phase of the Afghan War to a victorious end. Remained for Lord Lytton to gather the fruits of victory, which do not always tally with the aims of battle.

2

The swift—if partial—success of that three-fold advance changed the whole political aspect of India and Central Asia. It discomfited Russia. It justified Lord Lytton; and brought the ‘buffer state’ within the orbit of the new Indian Empire. General Roberts was awarded a K.C.B.; and the Kuram Valley Field Force remained more or less in being, either to create a new ‘forward’ cantonment, or to advance in fighting order, if need arose. And there were many who believed it would arise. Though British arms had triumphed, no great battle had been fought, no loss inflicted severe enough to shake the Afghans’ arrogant conceit of themselves. And it still remained for Simla to achieve a fair treaty with the new Amir.

To him Lord Lytton offered much the same terms as to his father, and they met—as he might have foreseen—with much the same reception. Yakub Khan would cede no territory; would admit no resident British officer, except at Kabul, justly arguing that he could not guarantee their safety in a land of fanatical Moslems. These flat refusals—dismaying to an optimistic Viceroy—convinced all experienced officers that only by a march on Kabul, and peace terms there dictated, could British supremacy be lastingly affirmed. But a strong anti-war feeling in England evoked the decree that, unless Yakub Khan proved actively hostile, a fair treaty must be drawn up, laying stress on an advanced frontier line and British influence paramount at Kabul.

To that end Viceroy and Amir exchanged reams of polite correspondence, resulting in partial acceptance of the terms proposed by Major Cavagnari, who would proceed forthwith to Kabul. On March the 29th he received a letter endorsing the Amir’s promise to conform, in all matters of conduct, with his sincere professions of loyalty to the British Government. On April the 4th there fell into his hands an intercepted proclamation to certain Border tribes, who had given serious trouble, bidding them have no fear of the infidels, against whom he would shortly launch an irresistible army.

‘And, by God’s favour,’ was his pious conclusion, ‘the whole of them will go to the fire of hell for evermore. Therefore . . . kill them to the best of your ability.’

Here, it seemed, was providential proof that any peace-treaty made with Yakub would prove a house founded on sand. But a man wedded to a policy contracts unconsciously a fatal will-to-blindness. Not even clearest evidence that the Amir spoke with two voices could divert Cavagnari from his fixed purpose: a British Embassy at Kabul. But that was to be—not yet. The Amir, still half-afraid of Russia, deferred the British visitation by proposing to come down and discuss his treaty in Sir Sam Browne’s camp at Gandamak—scene of the last stand made by a broken British regiment in the awful winter of 1841. So it came to pass that on the 8th of May, 1879, the new Amir rode into the British camp with his friend, Cavagnari, and an imposing escort; troops lining the road for three miles, presenting arms as he passed; the hills echoing to a royal salute.

Such was the brilliant first act of a drama that was to prove sufficiently tragic, in the issue, for all concerned.

From two weeks of incessant talking, there emerged a treaty more or less on the lines laid down: an increased yearly subsidy and a permanent British Envoy at Kabul; the Amir to guarantee his safety and honourable treatment, and to keep, if he so desired, an Afghan Envoy at Simla. As treaties go, it was fair enough. Yet there were many who doubted the wisdom of once more pressing an undesired ambassador upon a stiff-necked people, with so black a record of treachery, cruelty and evil-doing.

To the cautious few who spoke their minds, Cavagnari’s answer was conclusive: ‘If my death sets the red line on the Hindu Khush, I don’t care——’ To all forebodings and demurs he opposed his assured conviction, his notable personality and prevailing will. More: he begged leave of the Viceroy to prove in his own person the soundness of the policy that both men had at heart. And to Lytton it seemed no better choice could be made for so high and difficult an office than the remarkable man, whose tact and skill had engineered the treaty. So straightway he was appointed Envoy and Plenipotentiary, with a K.C.B. to enhance his prestige at the court of Kabul. And on a sultry May morning young Jenkyns—his Political Assistant—galloped away from tragic Gandamak ‘with a particular-looking tin case strapped to his shoulders’; all unaware that it contained the death warrant of himself and his distinguished chief.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Even at that early date Yakub Khan revealed, by certain minor decisions, how little he could trust either his own power or his own people. Why else must he ask for the Mission to travel by the Kuram route, instead of direct from Gandamak? Clearly the excitable, independent Khyberri tribes were masters of the situation. And a further request for six weeks in which to make arrangements, implied probable opposition from his more powerful chiefs.

Both requests were granted. Cavagnari left Simla for the Kuram Valley on July the 6th with Jenkyns, Dr. Kelly, a medical officer, and his mixed escort of Guides, commanded by Walter Pollock Hamilton, V.C., a cavalry subaltern, of whom great things were expected by all who knew him. Fair-haired and tall—over six feet—his fine physique and appearance were allied to soldierly qualities of mind and character that won all hearts, and had already won him the Queen’s Cross, in a gallant fight with Sir Sam Browne’s column; a fight worth briefly recording.

It happened that a battery of Artillery and a squadron of Guides Cavalry had been told off to disperse a horde of ghazis; and in the first charge, Major Wigram Battye had been mortally wounded. But the squadron, led by young Hamilton, swept on with the wild battle yell of the Guides, over broken country gashed with deep nullahs, eager to avenge the death of their beloved leader.

A sudden cry from the ground scouts gave warning of a cleft impassable for cavalry: a nine-foot drop into a narrow, stony river-bed, a sheer ascent opposite crowned with yelling, firing ghazis. But the guns were hard pressed; not a sign yet of infantry in support. So on went Walter Hamilton, scouts or no.

Urging on his charger, he sprang into the narrow gulf. ‘ And after him, scrambling, jumping anyhow, nohow, like a pack of hounds, streamed his fierce following. Scattering up and down the nullah in clumps of twos and threes, they found egress somehow. Then came death and the Prophet’s Paradise to many a brave soul. From here and there, from front and right and left, charged home those gallant horsemen; and at their head, alone with his trumpeter, rode Hamilton.

‘An onslaught so fierce and resolute—fit to shake the nerve of disciplined troops—very soon broke those brave, undisciplined levies into a tumbled, flying crowd, pursued by the exultant squadron till men and horses could no more.’2

To six of the troopers that charge brought the coveted Order of Merit; to Walter Hamilton a brilliantly earned Victoria Cross, for gallant leadership and for saving the life of a sowar, in mortal danger, set upon by three Pathans. To him, now, fell also the honour of commanding Sir Louis Cavagnari’s escort of Guides—twenty-five cavalry and fifty infantry. And no doubt there were many brother officers who envied him—at the time.

It was not till the 17th of July that Cavagnari and his party reached Sir Frederick Roberts’ camp beyond the Peiwar Kotal on his way to the new frontier line at Karatega, where he would be met by an Afghan Sirdar and General. That night he gave a farewell dinner party to disappointed officers baulked of the Kabul adventure. Cheerful and assured, alive to risks, yet confident of the outcome, he consoled them with the prospect of safe travel in Afghanistan next year. There were those who believed; but there were many who doubted. And among the last was none more troubled at heart than the little General, who knew too well the dangers of a premature peace treaty with a fierce and untrustworthy people; knew that those four fine men would probably never see India again. Called on to propose their health, he could achieve no more than the bare formalities, nor could he shake off the oppression of gloomy foreboding; while Cavagnari was full of plans for a cold weather tour along the Western Afghan frontier and arangements for his wife to join him in the spring. Yet there were those in Simla who had heard him say that the chances were four to one against a safe return: a view confirmed weeks later by wise old John Lawrence, when the news of Lytton’s forward move reached England. ‘They will all be murdered,’ he said—‘every single one of them.’ Possibly Roberts thought the same.

Next morning came the Afghan Sirdar with his Cavalry General, and the whole party rode off between lines of troops to the boom-boom of fifteen guns. At the boundary rock, they were greeted by the Amir’s 9th Cavalry—diabolical-looking scoundrels, in slovenly scarlet tunics, shabby helmets half over their eyes and chinstraps dangling on their chests. Hampered by that fantastic escort they rode on, Roberts with Cavagnari in the van: and while they talked, a solitary magpie flew past, unheeded by the General.

Cavagnari turned and said quickly: ‘Don’t tell my wife we saw a magpie: she would take it for a bad omen.’ And again a shadow of foreboding passed across the older man’s mind.

It was deepened that same evening by one of those curious chances, which men look back upon—and wonder . . .?

After a sumptuous Eastern dinner in the Afghan camp, and a cheerful ‘God-speed’ to the chosen four, Cavagnari rode half way back with the General. On the Red Kotal they parted cheerfully and rode off on their different ways.

It was then that Roberts—moved by some indefinable impulse—turned in his saddle for a last look at Cavagnari. To his surprise, the Envoy turned also at the same moment.

Without a word they both rode back, shook hands a second time, and parted—not to meet again.

3

There is a legend among Afghans—which speaks for itself—that when Satan, disgraced and defeated, ‘fell like lightning from heaven’, he fell on to Kabul City. Hence its black record of faithlessness and crime: a record that can show no darker page than the brief and tragic tale of Sir Louis Cavagnari’s Mission to the Court of England’s professed ally, Amir Mahomed Yakub Khan.

By the end of July 1879, he had made all arrangements for a political invasion secretly undesired; had prepared a Residency for Envoy, staff and escort within the precincts of his citadel, the Bāla Hissar.3 Built up the slope of a stony ridge, its embattled towers dominated the city—a rough triangle of flat-roofed houses wedged between outlying spurs of the Hindu Khush. Through the city flowed Kabul river. Beyond it lay ripening cornfields and vineyards and crumpled foot-hills that climbed to the snow line of the great main ranges. The lower Hissar was in itself a lesser town, with its own shops and houses and its beautiful Shah Bagh 4 below the Palace. The upper Hissar—a citadel within a citadel—commanded the whole of Kabul and her suburbs: the one point of strength in a singularly defenceless town.

For thirty-seven years no infidel Englishmen had entered Kabul, except as stray travellers. Now there came this bearded British Envoy with three other white men, all riding in gilded howdahs on state elephants, followed by their own Indian troops; Afghan regiments lining the streets to do them honour, by order of the new Amir, whose word was by no means law to his lawless people. But he had promised them that, when the Feringhis came, he would lighten all taxes and hearten his hungry soldiers with arrears of pay, long overdue. For if the Feringhi had few merits, he had usually many rupees.

Meanwhile, here was a fine tamāsha—infidels or no.

As the Embassy entered the Citadel through the Peshawar Gate, troops saluted, bands played ‘The Queen’, a battery of eighteen-pounders thundered a royal welcome. For Cavagnari, the arrival in state was the crowning triumph of his policy and personal ambition. He had faced all risks—not for himself alone: and here was his reward.

No shadow of coming events clouded their first week of a new life, new interests and duties. There were informal talks with a friendly, if unreliable, Amir. There were constant visits of ceremony from his chief Sirdars. Kelly was planning to start a dispensary. Walter Hamilton, hoping to promote friendly intercourse, encouraged the practice of sports—tent-pegging, lemon-cutting, and feats of horsemanship—in which Afghans were invited to join. Many accepted in a jovial spirit of emulation: but many more looked askance at displays of infidel prowess which seemed to say, ‘Thus will we split and slice all Afghans who resist the British Raj.’ And there were none to warn Hamilton of the false colour put upon his soldierly bid for friendship.

So, for all four Englishmen, the days passed pleasantly enough in their spacious quarters, near the palace: two flat-roofed houses of lath and plaster, built out from the wall of the citadel, round a vast courtyard. Above them, on the west, rose the battlemented tower of the Amir’s arsenal; but their south rooms looked out across the moat to open country and the far hills of Tazin. If there was only rough comfort, as Englishmen understood the word, there was decency and cleanliness, at least within their own precincts; a pleasant contrast to the chronic state of dirt and dilapidation that prevailed elsewhere. No wonder Cavagnari—riding daily through narrow lanes choked with filth and all abominations—dreamed of building a fine Residency outside the city, where he might welcome his wife in the spring.

It was near the middle of August that Kelly wrote to his father: ‘We are treated with every consideration by the Amir, who insists on our being his guests. We and our servants, horses and troops, are all fed at his expense. But the people are fanatical: not yet used to our presence. So we always ride about with a troop of cavalry. . . This is the time of the chief Moslem fast of the year. Between sunrise and sunset they may neither eat nor drink. But old Yakub gave us tea this morning after our ride.’

Thus Kelly, untroubled by dark hints that were already reaching the Envoy’s ears. Before July was out, he knew of the Amir’s promises to lighten taxes and pay his half-mutinous army, when the British came to Kabul: and on August the 6th he had clear warning of mischief on foot among certain regiments lately arrived from Herāt. It was brought by no scaremonger, but by a pensioned Native officer of Indian cavalry, Ressaldar-Major Nakshband Khan.

He told how these regiments had marched through the city led by their officers, bands playing, swords unsheathed, abusing the Amir and the Envoy by name. These doings, he felt, should be known of and checked. But Cavagnari dismissed, with an aphorism, his well-founded concern.

‘Never fear,’ said he, ‘Dogs that bark don’t bite.’

‘Sahib, these dogs do bite,’ the Ressaldar insisted, knowing his people. ‘There is real danger.’

And Cavagnari answered coolly, ‘Well, they can but kill the few of us here; and our deaths would be avenged.’ A brave answer; though it ignored the cost, in money and good men’s lives, of wreaking vengeance on the capital of a distant and difficult country.

The good Ressaldar, pained and puzzled, tried once again—through a Hindu of high standing—to enlighten a Sahib as blind as he was courageous. This time his obstacle was the sentry. Placed on guard by the Amir’s orders, he refused to let the Hindu pass: stoned and abused him for persisting in the attempt.

It was an insult that could not be ignored; and the Ressaldar, reporting it in person, ventured an outspoken comment: ‘What use, Sahib, in being here, if you are treated like a prisoner, not permitted to see men who only desire to tell you the truth?’

That pointed thrust took effect on a man proud to the verge of arrogance. He gave orders that the sentry be removed: and the Amir, when he heard of it, was exceedingly angry—not with the sentry for acting on instructions, but with his friend, the British Envoy.

An incident so equivocal must have disturbed any man whose eyes were not holden. In spite of it, Cavagnari failed even to utilise Lord Lytton’s offer of an advance on the Amir’s subsidy that would enable him to pay up his troops. He merely reported alarming news of rebellion and desertions all over the country and the mutinous behaviour of those Herāti regiments; adding, ‘I have been strongly advised not to go out, for a day or two.’

Those words of grave import appear to have troubled the Viceroy as little as they troubled Cavagnari. Heedless of warning, he went out as usual. Heedless of hints—and more than hints—that Yakub Khan was playing him false, he clung to his blind belief in the Amir’s good faith and acted accordingly. He withdrew his guard from the Residency gate. He rode out daily with a troop of Afghan cavalry and a few of his own escort. In talk with the Amir, or his Ministers, he resolutely spoke his mind as among friends. A keen sportsman, he gave more time to partridge shooting and to planning his grand tour with the Amir than to keeping a watchful eye on the trend of events in Kabul or elsewhere.

From the people he held proudly aloof, even from the Persian Kuzzilbashes, who alone were friendly to the English. He actually refused the offer of a house in their quarter, where he and his party would have been comparatively safe. He saw no reason, it seems, to consider the question of safety. Yet his own escort knew—if he did not—that no Sikh or Hindu among them dared enter the city; that even Moslems went armed; and all were treated to scowling looks or taunting words that they would think shame of repeating to their Sahibs. But among themselves they spoke freely of Afghan enmity, and prophesied their own coming doom.

It is a British instinct to challenge danger; and a man of Cavagnari’s natural courage may well have thought that the Mission’s best chance lay in maintaining a bold front, in tacitly assuming the Amir’s will and power to keep his given word.

If his companions were less blind or more sceptical, the Amir himself was receiving daily proof that—whatever his will—his power to enforce it was a negligible quantity. Sher Ali’s embittered hatred of the British—sown broadcast—was bearing fruit now to the discomfiture of his ill-used son. All over his kingdom Mullahs were preaching a jehād5 against the English; and unless he could win them over, he might be deserted wholesale. His fierce, wild people, his powerful Sirdars, had no tradition of loyalty even to an Amir. They could only be controlled by force of arms. He suspected that his brother, Ayub Khan—Governor of Herāt—had designs on Kandahar. He knew that his cousin, Abdur Rahmān—a man of resolute character—hovered in Turkestan, biding his time.

If these factors were not fully known to Cavagnari, he must have gleaned much disturbing information during his visits to the palace. Yet on August 30th he wrote privately to Lord Lytton: ‘I have nothing whatever to complain of as regards the Amir and his Ministers. His authority is weak throughout Afghanistan; but, notwithstanding all that people say against him, I personally believe he will prove a very good ally, and that we shall be able to keep him to his agreements.’

Thus, by his over-sanguine conviction, he succeeded in deceiving himself and others—to his own undoing.

On September the 2nd, he wired to Simla, ‘All well with the Kabul Embassy.’ And next day, before sunset, Embassy and escort were all dead men.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

That morning, the Residency party rode out as usual. That morning, also, the Herātis, in Sherpur Cantonments, were ordered up to the Bāla Hissar to receive full arrears of pay. There they paraded, unarmed, at eight o’clock, in the pay garden, not a hundred yards from the Residency: and there they were told that the Amir could give them no more than one month’s pay—a miserable pittance for hungry men.

Baulked and angry, they demanded full payment from Generals who were powerless to go beyond their orders. One of them, it is said, shouted angrily, ‘If you want more pay, go to Cavagnari Sahib. Plenty of money there.’

The incitement—deliberate or no—sent them to Cavagnari: a rush of maddened, hungry soldiers, genuinely hoping for redress——

And while mutual altercation swelled louder, four unsuspecting Englishmen, within the Residency, were taking up the day’s routine after their early ride: Hamilton and Kelly at stables; Cavagnari waiting for his bath; the Guides—not yet in uniform—taking their ease; the cavalry in an outer enclosure, tending their picketed horses. The angry interview in the King’s Garden concerned them not at all. Afghans were excitable people, given to much clamour.

And suddenly, to their startled ears, came the rising roar of an angry crowd; three regiments of defrauded soldiers yelling for Cavagnari, demanding money with curses and threats. Before the full danger was realised by officers or men, the Herātis had rushed the walled enclosure. Hustling and stoning the sowars, they untied their horses, plundered swords and saddlery; shouting ‘If we can’t get money, we’ll take all we can.’

Stones hurtled at the Residency windows. The gates were closed against them; and Cavagnari—appearing on the lower roof-top—called out to them that they had better go elsewhere, as the matter of pay was not in his hands.

They showed no inclination to go elsewhere: and suddenly, above the uproar, a shot rang out—another—and another——

Who fired them, none ever knew. But the sound of a musket changed the temper of the crowd. Instantly they rushed off to fetch arms and ammunition from Sherpur, two miles away.

And when they were gone, there fell a pause. . . .

That brief respite from the sudden and startling onslaught, awoke full realisation of the impending danger in the Residency—and in the palace over the way. It was the Amir’s one chance, that day, to prove his active goodwill toward those whose personal safety he had guaranteed. For the Herātis had two miles to run each way; and there were troops of his own at hand: a regiment guarding the treasury, an arsenal full of ammunition, and some two thousand armed followers around his palace. Had he sent even a guard of these across to the Residency, the final tragedy might have been averted. Yet nothing was done.

While his mullahs and syeds urged him, in the name of hospitality, to save his guests, he merely stood outside the palace weeping and tearing his hair; high officials gravely looking on; three batteries of artillery standing to their guns.

In vain the head mullah protested, ‘Why are you crying here? Your guests will be murdered!’

‘My kismet is bad,’ he wailed. ‘What can I do?’

‘You can order your guns to fire when the regiments return.’

‘What use? The city badmashes will come and eat us all up.’

‘Bismillah! At least you can die, rather than disgrace Islam.’

But Mahomed Yakub Khan preferred to disgrace Islam.

He sent no guard over the way, he retreated into his palace, still weeping and tearing his clothes. And when an urgent call came from Cavagnari—claiming royal protection—he sent the temporising answer of his kind: ‘As God wills, I am making preparation.’

For all that, his troops never once fired on the Herātis, the Bāla Hissar gates were never closed against the scum of the city, who soon came hurtling through them, armed with swords and knives, shouting, ‘Kill the Infidels! Kill—Kill!’

He deliberately left his Ambassador and staff—with their escort, servants and followers—to put up a hopeless, heroic fight against hundreds that soon swelled to thousands.

That they were doomed men they must all have known within the first half hour. The Residency itself was ‘a regular rat-trap’; both flat roofs—their only vantage grounds—overlooked by many other roofs, and almost within pistol shot of the arsenal bastion, that towered sixty feet above them. On three sides they were surrounded by houses and narrow lanes; the fourth formed part of the outer wall.

While young Hamilton collected his men and made impromptu dispositions, Sir Louis Cavagnari awaited the Amir’s futile answer in no enviable frame of mind: his faith in Yakub Khan rudely shaken, his eyes rudely opened to the fallacy of his own vain dream and the Viceroy’s insistence on an Embassy at Kabul before the hour was ripe. Looking out, for the last time, on the far gleam of snow-peaks in the early light, he must have felt a pang of conscience at thought of his doomed companions.

Doomed or no, they would all die fighting; their desperate resistance heartened by a hope that the longer they held out, the better chance for the Amir to pacify his mutinous troops.

Too soon unmistakable signs heralded the return of those three regiments fully armed; their numbers swelled by other troops and by all the scum of Kabul city. Out of every unclean street and by-way they swarmed through the unclosed gates, with the awful composite roar of men who have fallen lower than the beasts that perish—men craving slaughter for slaughter’s sake.

And above the din of voices, the rush of trampling feet, rose the fierce ‘Yar-charya!’ war-cry of the Sunni sect of Moslems, their blood-lust intensified by the prayer and fasting of Ramzan, by the certainty that not a man among those trapped infidels could escape the fires of hell.

With the return of the troops there began a systematic and determined attack on both Residency buildings, ably assisted by an armed mob. From the arsenal, bullets began dropping on to the Residency roof held by Hamilton and his men. For them, no shred of cover, no chance of target practice against assailants crouched behind parapets, dealing death without risk to life or limb. Not so Cavagnari. Lying flat on the exposed roof of his own quarters, he was coolly picking off enemy leaders with swift precision. Four of them he had killed, when a splintered bullet struck his forehead and put him out of action.

From that time forward, the whole burden of defence was laid on young Hamilton, with Jenkyns to share his desperate task, while Kelly devoted himself to the wounded: more and more of them, as firing increased from the house-tops, from lanes and walls, whence the mob so fiercely pursued their harassing tactics that Hamilton ordered a charge in the hope of driving them off. Inevitably they would return; but there was virtue in every ounce of respite from the tireless assault. In that first charge the wounded Envoy himself took part; and the astonished Afghans, boldly attacked, turned and ran—in the words of an eye-witness—‘like sheep before a wolf’. They were destined to be increasingly astonished before the day’s ending.

Though the Guides killed many, they were slowly beaten back: and after the first charge, Cavagnari was no more seen. Only a hurrying sepoy caught sight of him, laid upon a bed, his feet drawn up, hands clutching his head, Dr Kelly bending over him, doing what he could.

So died Cavagnari—a very brave man, whose courage covered many imperfections of character and judgment. Fortunate he, to be spared the terrible hours of strain and torment long drawn out.

For now they were beset by peril more immediate. The rebel troops had bored rough loopholes in the walls. Rifle muzzles spat and crackled at close quarters—a murderous fire. The very rooms became untenable. Now the Afghans brought ladders and ran up them like monkeys. On to the roof they swarmed, yelling and brandishing blood-stained knives, forcing the few Guides, who manned the parapet, down the steps into the house, rushing boldly after them—to their undoing. For the Guides had drawn them down only to turn on them in the narrow space, and kill and kill, driving out the discomfited invaders.

Once again a letter had been smuggled to the Amir, with no more result than the first. That it reached him is known; for the messenger lived to tell how, on arrival, he was bidden to wait for orders—that were never received; how, in the palace, all was terror and indecision. The Amir—guilty or negligent—was now thoroughly alarmed; fearful lest the city badmashes, in their fury, should turn on him also for his friendship with infidels.

Because of that fear, he refused to fire on the crowd. Instead—shamed by reproachful mullahs—he vainly sent out his eight-year-old son, with a few Sirdars and the boy’s tutor, holding aloft the Koran, urging an infuriated mob, in the name of God, to cease their bloody work.

Instantly the book was snatched from him, flung down and trampled on; pleas and protests drowned in yells of rage, rattle of musketry, crash of tumbling walls. And the terrified ambassadors beat a hurried retreat, thankful to escape with their lives. General Daoud Shah, riding out with a few troopers, was unhorsed and stoned; and the mullahs—having done what they could—retired to pray.

No leisure for prayer on the far side of that surging multitude; no terror and confusion, no indecision; though for five hours the fight had raged with unceasing fury; though half the garrison had been killed and wounded, and Kelly’s hands were over full.

On Hamilton fell the three-fold strain of cool planning, desperate resisting, and keeping up the hearts of his men. For the Moslems among them were assailed at intervals by shouts from Afghan officers: ‘Give up your Sahibs, and you shall go free. We have no quarrel with you. Be not fools, to fight with accursed Feringhis against the Faithful.’

And the Guides gave them, for answer, a stinging shower of bullets from the rifles of the White Queen.

By now they were hemmed in—above, below, on every hand; adjoining houses and roofs alive with dark faces and scurrying forms; their own roof untenable; their number reduced to thirty men under one stout-hearted Jemadar; rooms and courtyard choked with dead and dying, oppressive with smoke of powder and shot.

Suddenly, through that familiar nightmare, came drifting wraiths of smoke other than powder; and the fatal smell of burning wood told them the basement was on fire. Afghans overhead, devouring flames below: between hell and its devils, they were trapped indeed. Yet none spoke or thought of surrender. Only, for the third and last time that day, Jenkyns made a foredoomed attempt to remind the Amir of his duty as host and ally.

His messenger—an Afghan Prince serving as cavalry trooper—sprang fully armed, straight from the low roof’s edge, into the jaws of a hundred baying wolves, many of whom unwillingly broke the shock of his fall. Before they could seize him, he was pushing his way through the crowd, flinging up his arms and crying, ‘Peace! Don’t shoot. I am one of you. I bear a message for the Amir.’

In speaking, he recognised a friend—and so won through to the royal apartment, where the ruler of Afghanistan cowered lamenting, among his women. Useless, he said, to come asking for help. Man could do no more. They were all in the hands of God. But the trooper, like his fellow, was kept in the palace. He could send no word to the Residency: worse still—no help.

And now, from that direction came the fatal thunder of big guns, that told him the end was near. Against guns, even the bravest, in that battered, burning house, could scarce hold out for an hour. So he believed, though for years he had known the Guides and the officers who led them.

He was mistaken. They continued to hold out—in the teeth of all that devil or man could do against them—with a stubborn courage that has seldom, even in British annals, been surpassed. Loud and exultant shouts announced that two guns had been trained on to the main gateway: and the Guides—half stifled with smoke, driven by fire and shot from room to room—responded as one man when the boy Hamilton commanded a desperate attempt to capture or silence those fatal guns.

They were but twelve against thousands; and in ordinary warfare the command must have sounded like madness. But this was no ordinary warfare; these were no ordinary men; lifted as they were above human stature by the terrible exigencies of the hour.

As the door was flung open, they charged straight at that howling mob, led by Walter Hamilton, a splendid figure of young manhood, lithe and strong and of good courage.

Unscathed they crossed the deadly bullet-swept courtyard, and fell with fury on to the amazed gunners and the crowd behind the wall. Shooting, thrusting, slashing, they killed or routed every man round the guns; seized them, swung them round and even dragged them a few yards, heedless of bullets that rained from all sides. But men were falling fast; and the overwhelming return of dispersed Afghans drove them at last back to the open door with the loss of half their numbers. In that sortie the end came for Kelly, who had left his wounded to join in the soldierly attempt, and died a soldier’s death.

But no pause was permitted them to grieve for the loss of a comrade and six good men.

Almost at once a second salvo shook the building: and Hamilton, in the same breath, ordered yet another charge. Hopeless or no, something must be attempted, if they were not to die like rats in a hole. Again they flung open the door; again rushed out, as though they were half an army, instead of half a dozen Guides and two Sahibs, who knew not the meaning of defeat.

There Jenkyns fell, wielding a sword he had never learnt to use; but on went Hamilton, untouched by bullet or bayonet, as though he bore a charmed life. He and that handful of resolute men once more drove off Afghan soldiers and seized the guns. For a few yards they dragged them, exhausted though they were with the heart-straining struggle of a task beyond human power. Engulfed by the returning tidal wave, fighting foot by foot, they were forced back into the burning house, where devouring flames curled upward, charred woodwork crumbled, roofs fell in with a dull crash, burying dead and wounded in one awful grave.

No refuge, now, for the few survivors, but an underground bath-place of solid brick. There they could breathe and take a few moments’ respite, after seven hours of Homeric struggle: but there, very soon, they would be found and cruelly killed by one of the cruellest races on earth. Better to die fighting, no matter how forlorn the hope. So the dauntless Hamilton laid his plans for yet another sortie: to capture even one gun would delay the end, give the Amir a further chance of subduing his people—if he could or would.

Three of the Guides were to fire through a rift on the assailants; the remaining three to charge out with him.

‘I, alone,’ he said with superb assurance, ‘will face the enemy. You others pay no heed to the firing. Harness yourselves to the gun and bring it in. Then we will charge out again and capture the other.’

A noble order; nobly obeyed.

Out again they dashed—three men and one tall officer with an élan that must fairly have staggered those rejoicing Afghans. A third time they captured the gun, while Hamilton alone confronted the enemy. Sword in his right hand, pistol in his left, he towered conspicuous, facing certain death with the same high courage that he would have faced life, had he lived.

Bullets rained. Endless Afghans surged forward, waving naked blades. Fierce dark faces. closed in on him, as he stood there slashing and firing, right and left, guarding his men and the captured gun. Singly, he was a match for the most stalwart: cool, swift, alert, as if he wore bullet-proof armour.

Parrying a thrust at his throat, a slashing stroke at his head, he had sabred three Afghans and shot three others before they made a concerted rush to overwhelm him. Cuts and thrusts, too swift for mortal man to parry, sent him staggering to the ground—undefeated in spirit to the end——

And over his dead body they swarmed; recaptured the gun, and swept back into the house those few remaining Guides—hungry, exhausted, leaderless—who would surely now surrender at discretion.

So they supposed, in their ignorance of the spirit that pervades all ranks of a disciplined army. Men, who had seen their dauntless leader cut down, were in no mood to make terms with his murderers.

In vain the Afghans shouted, ‘Why fight any longer? Your Sahibs are killed. Surrender—and we will give you quarter.’

‘We surrender no Government property,’ the stout-hearted Jemadar Jewand Singh flung them his answer. ‘We obey our Sahibs’ orders, alive or dead. We are fighting for the fame of the Guides.’

So they marched out, the six of them—resolute to kill and kill, while breath remained in their bodies.

The tale was told by a soldier-prisoner—himself imprisoned—who looked out from a window on those final sorties—and bore witness to the valour of Jewand Singh, who out-lasted all his comrades, and accounted for eight Afghans before the inevitable end.

By sunset, on that 3rd of September, there were neither Guides nor Englishmen in Kabul any more. But around them lay some four hundred Afghans, dead or dying, witnesses to a defeat that might rank as victory.

And from afar off the old Mullah, who had urged Yakub Khan to action, saw that which had been the Residency shrouded in dust and smoke and leaping tongues of flame; saw the mob flocking back to the city, shouting the good news that all the Kafirs were dead.

‘Then I knew,’ he said, long after, ‘that the English would come to Kabul.’

Phase II

1

In Simla an unusually brilliant season was nearing its end. Few among the crowd of busy idlers gave more than a passing thought to the successfully-accomplished Kabul Embassy. If the Viceroy had any private qualms, he never spoke of them; nor did General Roberts, who had spent the summer in Simla at work on an Army Commission, and had laid his plans for long leave at Home.

On September the 4th he fell asleep, untroubled by thoughts of Kabul; and in the small hours he was awakened by his wife.

A man with a telegram—she told him—was wandering round the house, vainly calling and calling. At once he sprang up and hurried downstairs; he opened the flimsy envelope, and read—with a shock of horror—a message from the Political Officer at Ali Khel. A Ghilzai from Kabul had brought news of the sudden attack and the brave defence. He had left before the end came; but too well Roberts knew what the end must be. Early as it was, he dressed and hurried off to Viceregal Lodge; found Lord Lytton in council, stunned by the very worst that could have befallen him, anxious to suppress the news till all was known.

Within twenty-four hours the shock fell on Simla, shrouding the last of that brilliant season in gloom. It fell on the Guides—in their regimental home at Hōti Mardān. It startled and horrified incredulous men and women all over India. It smote Lord Lytton, as man and Viceroy, through the loss of his friend, Cavagnari, and the collapse of his untimely Kabul Mission. Once more Afghanistan had scrawled across the page of history her savage declaration of independence in letters of blood and fire.

The Amir—or his people—had scored a point in terrible fashion; but theirs was not to be the last word.

The invading armies must again be put on a war footing. They must strike—and strike quickly. Sir Sam Browne was bidden to re-form his Khyber column; Sir Donald Stewart to stand fast at Kandahar. The Kuram Field Force still crouched vigilant on the Afghan frontier, like a cat watching a half-stunned mouse. Given luck and spirited leadership, it might reach Kabul in five or six weeks; and punishment, to be effective, must be swift.

By good fortune the very man to push it through was still in Simla. No well-earned Home leave for Sir Frederick Roberts. Without a moment’s hesitation, without bargaining for a larger force, he agreed—given picked officers—to undertake a task that few Generals, if any, in India would have cared to face with less than 20,000 men. But he knew there would be two other columns in the field; and he counted on reinforcements from the Khyber when he reached Kabul. Meantime the Amir was informed that a British Army was rapidly advancing to strengthen his hand and punish the murderers of a British Mission.

To Roberts at parting, Lord Lytton gave one clear injunction, ‘You can tell them we shall never altogether withdraw from Afghanistan.’

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Within a week Roberts found himself on quite another hill-top, in a temporary cantonment of logs and huts. Here, round a shabby camp table, he and his Political Secretary, Mortimer Durand, were gravely conferring with two Afghan magnates—Finance Minister and Wazir—sent from Kabul to discuss the painful situation; and, if possible, to delay his advance; though they cloaked their true aim under fulsome professions of fidelity from the Amir. Roberts could only explain that his orders were urgent; that the honour of his country was involved; and nothing would satisfy the English except a British army at Kabul punishing the murderers. Three columns—he told them—were now advancing in such strength as to make resistance impossible. And the Afghans, openly dismayed, departed in haste, lest these infernally active British might be in Kabul before them.

But British activity had first to contend with lack of transport, and supplies for the half-starved camels and bullocks: reports of forage so short, on Shutar Gurdan Pass, that the battery mules—omnivorous folk—were eating up their own and their comrades’ blankets, even the hair on each other’s tails. But if deficiencies and anxieties were many, the warlike temper of men and officers atoned for all. In them the spirit of Agincourt lived again; ‘the fewer men, the greater share of honour’; and their rousing welcome had given him full assurance that ‘whatever it was possible for dauntless courage, determination and devotion to achieve, would be achieved in the face of all obstacles.’

Now it was ‘forward’ at last—would the Afghans or no: down and up, down and up—the eternal see-saw of hill marching—to the high plateau of Shutar Gurdan, the Pass of the Camels’ Neck, less than sixty miles from Kabul.

Dropping down from Ali Khel they entered the gloomy, rock-bound defile, with a horrid sense of mice creeping into a trap: out again to the next camping ground, and a night’s rest by the way. Then on, in not too orderly fashion; crawling like flies up the steep, zig-zag of Surkai Kotal; the roughest marching they had faced since Peiwar. But at last they found themselves on Shutar Gurdan plateau—dead beat, every man and animal; a whole camp to be pitched before any could hope for food or sleep.

There Roberts was dismayed by an embarrassing message from General Baker, at Kushi, that the Amir had just ridden into the British camp, with his eight-year-old son, his father-in-law, and his Commander-in-Chief, Daoud Shah; a suite of forty-five retainers and an escort of two hundred men. For his nominal rule had perished with the Mission. He could trust neither his troops nor his Ministers; and many Sirdars were in open revolt. Secretly he had fled from his pleasure garden at Ben-i-Hissar, and had ridden by night through the Logar Valley to Baker’s Camp, confiding in the indulgence of the great Government whose faith in him he had flagrantly betrayed.

General Roberts, himself, was in no mood to welcome a royal mark of confidence, which, doubtless, betokened further anxiety to check his hampered march; nor had he leisure for anything but the stiff task before him. Down from the Camel’s neck they zig-zagged, and were lost to view in another stupendous defile, aptly named the Gate of Hell; out again, and up the rocky Shinkai Kotal, whence they dropped into the gentle Logar Valley. There Kushi—Land of Delight—lay hidden in a long ravine; a true oasis—shade and water, orchards, melon beds, and vines heavy with grapes. Here Sir Frederick Roberts must greet his undesired guest, with whom he was to become dismally familiar as a problem, an embarrassment and a possible traitor in his camp.

Yakub Khan, at two-and-thirty, was a shifty-looking man of Jewish aspect, his furtive eyes bloodshot, his forehead retreating abnormally under a sugar-loaf hat; his moustache and beard masking a weak mouth and chin. Neither Roberts nor Durand were favourably impressed; and in camp he was regarded with a mixture of curiosity and hatred. The Sikhs were restive; and even kindly British officers would most of them have voted for hanging the man who might have saved the Mission if he would. But on the surface all was courtesy and ceremonious exchange of visits; a guard of Scottish troops for the Amir’s camp—ostensibly to do him honour, actually to keep an eye on the constant coming and going of messengers, who might well be used to betray the movements of his so-called friends. In any case, he was openly anxious to delay the British advance. But Roberts—hampered every way—had resolved on a bold, if hazardous, forward move, trusting to local headmen for provisions and carriage.

Even so, it was not till the end of September, that he at last felt fully prepared to launch his famous ‘swoop on Kabul’, described by a distinguished officer who took part in it as ‘simply the most daring and brilliant feat of arms performed by any British General since the Peninsular War.’ The writer adds: ‘I don’t think people in England have yet realised what this march was; and I am sure they have never done it justice.’6

There were others—inevitably—who criticised Roberts for temerity in marching ill-equipped through a hostile country, with a high mountain range cutting him off from India. Such criticism disregarded the impromptu nature of the whole campaign: an army—unprepared for renewal of war—called upon to invade the most difficult country on earth. That army knew itself fortunate in being led by a General who would not let the grass grow under his feet, while he scratched his head over the next move. Like all born soldiers, he was fully aware that, in war, psychology counts for more than numbers, and he everywhere re-affirmed Napoleon’s golden rule for victory, ‘to be quicker than the other man’. But he had wisely halted at Ali Khel, to keep the tribes wondering, and to ensure enough supplies at Kushi for a swift forward move. The least sign of wavering, once he had fairly started, would be the signal for a combined onslaught that could have one end only—annihilation.

And now, to the enemy without, was added the embarrassment of a fugitive Amir, whom he suspected—rightly or wrongly—of playing a double game. But intent on his one object—Kabul, he kept a cool head, an invincible heart; and the knowledge that he never doubted the issue was worth a regiment to his travel-weary force, now virtually marching en l’air. Except for the helio flash—sunlight permitting, and a runner postal service—Afghans permitting, they lived and moved in a little world of their own, self-supporting, self-contained: a unique achievement of its kind. Warm, clear days and a full September moon conspired with the spirit of their leader to promote the swift advance on which his resolute will was set.