Midst Himalayan Mists

Preface

In these chapters is set out the story of the author’s journey to the Tibetan passes. The narrative is more in the nature of a personal record than a guide for tourists, and the writer submits them for what interest his own experiences may have to the casual reader.

The chapters were all originally published in The Englishman.

— R. J. Minney

Chapter I

Introductory

The journey to Darjeeling is to most people an every day event. Darjeeling has become a resort of foremost importance to Bengal and its comparative ease in accessibility by rail has made it a week-end affair with husbands anxious to pay a fleeting visit to their winter wives.

But for one traversing the route for the first time the journey does not fail to hold out endless attractions. There is primarily the novelty of the little train, its winding, squeaking, climbing, puffing; the manifold beauties of the mountain-side, which are unfolded at every bend of its irregular conformation; the descending mist; the floating clouds; the tall, alpine trees, a-weeping with creepers---in all a varying combination of white and grey and dark green. Here through the fringes of the hanging mist peeps out the red thatch of a lonely plantation villa; a telegraph post; or the silver shimmer of a crashing water-fall; and all step back again into the deep grey of the unfathomable mist. There may be seen the panorama of the plains---a stretch of fresh green a-pimpled with habitations, and now the advancing mist comes down upon it and blots it out of the view of the Himalayan sojourner. The mist is the Puck of the mountainside; it loves nothing so much as to play its little pranks with the varying objects of alpine grandeur.

Darjeeling with its fairy lights and multitudinous attractions; its climbing houses; its cosmopolitan bazaar, where villagers come from afar each Sunday, some to barter and some to buy, and where John Chinaman has a rag and bottle shop; its variety of races---the Nepalese, the Bhutanese, the Tibetan, and the Lepcha, amidst whom are now entwined the Hindu, the Mussulman, the Parsee and the white man; its commanding views of the majestic, silent snows;---is a holiday resort that is well-known almost the whole world over.

We have all heard perhaps its brief history: how it was conferred as a gift of gratitude upon the British Government for their services to Sikhim at a time of Nepalese aggression over eighty years ago; how it was almost instantly selected as a sanatorium; how later, for treachery, the Terai, the intervening forest between this hill top and Calcutta, was wrested from the Sikhimese grasp, and how in the course of time, forty years later, the present marvel in alpine travelling was opened by the Government. I will leave Darjeeling to the guide book and to the many who have already sung its praises.

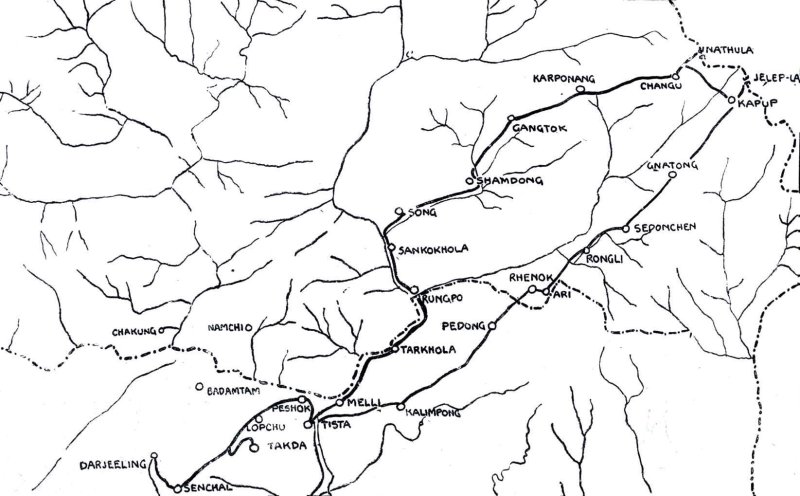

The roads to Tibet are many. One leads straight off the Chowrasta---the most fashionable of Darjeeling’s walks---down through the Rungit valley up to the Jalep La, a distance of but 80 miles. And beyond is the land of mystery and hush concealed once again from the gaze of the white man.

On a fine day the scene beyond stretches for miles into the distance. Writers have even set down that from the top of Observatory Hill, above the Chowrasta in Darjeeling, one can see some of the famous passes into Tibet. But what strikes one most from this irregular, rugged road that slopes down and down almost into infinity, is the row upon row of ever darkening hills that deepen into the distance. On the right crouches a monster hill---a solid block in the twilight, with clouds clinging around it like lather after an incompleted shave. Here---a landslip---all the hair has been carefully removed, and there a line of gaunt trees on the horizon, suggests the remnants of a stubbly beard, soon to be lathered over.

Tibetan Temple below Darjeeling](image.jpg)

But the morning is the time to view this hill-side, when the air is as often as not very much clearer. Select a Sunday and the scene is heightened by the colour and panorama of the streaming thousands from the surrounding valleys, all bowed under the burdens of their baskets, toiling ever up hill towards the stalls of the Darjeeling bazaar. Here goes by a Lepcha in his one-time white rags, now begrimed and dirty; there a Bhutia family in their dirty long blue coats and their swinging pig tails; here again some Nepalese children in pink head-dresses, and pretty coral neck chains; there Bhutanese nobility, with clean combed hair and garments of deep blue plush and red sleeves; here some Tibetan mendicants with their close-cropped heads and stooping gaits suggestive of the lama in “Kim.” Others again in printed pinks, and all with a wealth of fanciful adornment, immense glass beads of green and red and yellow; jade and silver bangles and anklets; nose rings, ear rings and quaint hair adornments.

One at last understands where ‘the silver of India’ goes to. Village women by the score, some no better dressed than coolies, wear innumerable strings of silver coins descending in widening rows right down to the waist line; and as they swing by in their measured tread one notices the currency of His Majesty’s Mint----four anna pieces, eight anna bits and rupees. Anklets and chaplets of silver too suggest some previous incarnation as a medium of currency, prior to the smelting fire of the goldsmith and his assembling hammers.

They all pass in strings, chattering, smiling, laughing, singing. In the evening twilight their dark figures will move again along the path like shadows on the hill-side and the burden of their song arising from the fullness of a heart contented with the success of the market day, is all there will be to tell that these shadows are iotas of humanity.

Chapter II

The Start

Although the direct road to Tibet lies through Kalimpong on to the most negotiable of the frontier passes, I chose instead the route through Gantok, the capital of Sikhim, and thence to the Tibetan border. This gives one an opportunity of viewing some of the greater glories of the Sikhimese countryside.

Mr. S. W. Laden La, Deputy Superintendent of Police, Darjeeling, very kindly assisted me in mapping out my tour and put me on to a Sikhimese guide who came before me armed with a volume of chits that would have made any Government file blush beyond its red tape and a Calcutta cook green with envy.

The guide proved to be worth his weight in gold. The chits told me that he had been found so by His Excellency the Governor, by the Hon. Mr. Gourlay, who left the Governor to assist Lord Sinha at the Peace Conference, by the Hon. Mr. Kerr, a Russian Princess, and numberless others. Apart though from his many qualities the guide has a countenance that is inspiring of humour. Yet his face is not the most funny part about him; for his name, Chingri Naspati, sounds like an entire meal in itself---a sort of a meagre luncheon.

The arrangements for the start were quite elaborate. The luncheon guide demanded about a quarter of the entire cost in advance, in order, apparently, to bribe himself and the coolies to undertake the rigours of the journey. However, as reports have occasionally come through of unreliable coolies who do not arrive at the halting stages in time to give you your meals or your bedding---detained presumably by drunkenness; and of others who run away with one’s belongings, my thanks are entirely due to Sirdar Chingri Naspati for his excellent arrangements, as a result of which every thing went off without a hitch---and came back too, I am glad to say, in the same condition. To this I have already testified in a personal contribution to his voluminous chit book.

The weather was excellent. The coolies---man, woman and daughter---appeared a little after dawn and started for our first halting place, Pashoke, 17½ miles out Darjeeling. The Sirdar called with the horses at 10 that morning.

Up to Katapahar the roads were as frequented as they are in Darjeeling. Beyond, the path narrowed, but numerous traders from Ghoom and further still passed in a steady stream. Just outside Jorabangla---the crossing point at which the railway passes through a Bhutia busti---sat an aged Lama mumbling to himself the universal prayer. My Sirdar passed him on horseback, and neither by sign nor sound did he pay him that respect that we in Calcutta are accustomed to see given the Brahmin as his special due.

The road wound out of the misty head of Ghoom, where that place gave us its proverbial drizzle. We next passed the road that leads up to Tiger Hill and Senschal and I was told it is the particular position of Ghoom between the three eminences of Katapahar, Senschal and Tiger Hill that gives it its name.

The mist still clung to trees and gave them a most unsubstantial appearance. Pale grey covered every thing I could see beyond the khud line.

But on the road there was traffic enough. Now there went past a Catholic Father, with flowing beard and gentle eye, who greeted me after the fraternal manner of his order. He was coming, my guide told me, from Takda cantonment, where a Gurkha regiment is quartered; and the priest pays a twice-a-week call to minister the requirements of the faith to the officers of that regiment.

“At Takda,” my guide went on, “are also the interned Germans of Darjeeling and elsewhere.” And there passed by presently under police escort, a wagon, which, I was told, had just deposited its load of rations for the Germans. So the Huns here at any rate were well looked after.

My guide told me that the Germans lived, some in barrack-like buildings, others in separate houses, all under charge of a British Officer. They were all there, men, women and children; and no doubt some of them may have required the attention of the Catholic Father.

I should have liked to have seen them but Takda lies about five miles below the main road and a visit of such a distance---plus the return over the same track---was too big a detour with Pashoke still some miles before me.

The human panorama continued to pass. A Brahmin in saffron drapery and headgear bowed most meekly; a red-turbaned Marwari also gave me his greeting---truly the courtesy of the road is commendable! Nepalese youths laden with elongated barrels, iron-hooped, containing milk for the market; men with timber and basket loads of charcoal. A woman came along bearing upon her head two enormous planks that stretched across our path as a moving barrier. At the admonition of the Sirdar, she turned herself and the planks towards the hill-side, and we passed onwards.

In two hours after starting we overtook our coolies, who were breathing heavily below their burdens. The man walked by himself in bowed meditation. The mother and girl strode in single file close to the edge of the hill-side. The girl was one of the cheeriest creatures it has ever been my lot to see. In this land of Himalayan happiness, almost everyone is grinning or smiling. But this little girl, despite the bending weight of her burden was laughing, always laughing. She laughed if the Sirdar sneezed; and her mother had but to reprimand her when she set off again into further peals of laughter.

The road is marked with water troughs placed at intervals as a benefaction to travellers by some aged Buddhist or Hindu who is endeavouring thus to spur on his progress to Nirvana. At one such stop the coolies unloosed their burdens, washed their faces---another blow to the belief in their uncleanliness---and rested awhile their weary limbs. The Sirdar and I meanwhile pushed on to our destination.

Pashoke lies almost at the bottom of the valley, only 2,600 feet above sea-level. The road to it is a steep descent which though tiresome for the horses has the compensation of beauteous vegetation upon the hillside. Down, down, down, through thickly wooded slopes; down, down upon a carpet of damp, trodden leaves; down where each bush is spotted with brilliant hues of fragrant flowers and where picturesque butterflies flutter; where branches of many trees stretch down their great arms towards you; down amongst the sounds of the chockchafers, the whirl of the waterfalls and the smell of the tea gardens,

At about 1-30 I arrived at Lopchu, 14 miles from Darjeeling. Here a little rest-bungalow stands a little way above the busti. At this bungalow I stopped for lunch. My coolies went on to Pashoke.

The bungalow was occupied at the time by a young Australian missionary from Faridpore, who was enjoying a little holiday from his rounds of technical instruction to Indian converts, and had a wealth of information to give me of the various settlements in India which are provided for from funds from Australia. At Pabna is a women’s centre where lace-making is indulged in; at Faridpore carpentry for boys; at Mymensingh higher education; and missionary work is also being carried out at Arnakoli among the Namasudras, as well as in the Garo hills amongst the aborigines.

Some of the dak bungalows on the route are stocked with a sprinkling of literature. This one had in a retiring cupboard somewhere at the back of the building many volumes of a religious nature that were presented by a Church of God Society. Two or three books that once belonged to the Amusement Club, Darjeeling, were re-stamped “Darjeeling Improvement Fund”---presented to isolated dak bungalows for the delectation of travellers.

From Lopchu the gradient grew steeper. At a corner the road folds back upon itself and traces its way to the Pashoke rest-bungalow through a tea estate which was alive with coolie women. Streams of them flowed past, each with her basket filled with the green pickings, amidst which nestled their little bratlings. Each woman knitted as she went by, glancing up coyly at us, or humming the air of an ancient Nepalese ditty. For the coolies of the tea estates in the Darjeeling district are all emigrants from Nepal and appear to be quite happy in their brown thatched settlements that cluster in groups around the factory building.

Chapter III

The Road to Rungpo

A long avenue of bare, lanky trees preceded the dak bungalow of Pashoke. The bungalow itself was in a pleasant spot amongst butterflies and flowers, wooded vegetation, and within sound of the ripple of the Rungeet and the laughter of the tea garden coolies. There was no one else there but the chowkidar, and in a very little while an excellent dinner of the Sirdar’s preparation eked out with tinned provisions was served up on a table beside an oil lamp which rattled at every footstep in the building. The Sirdar served up with the dessert one of his best Hindustanee stories, the telling of which I shall reserve for a later chapter. I was in bed by 7-30 and was lulled to sleep by the pouring rain which also had the faculty of disturbing me sometimes during the night, when I was able to see my watch glowing the small hours of the morning through the darkness.

The dawn was gorgeous. The rain had ceased and ere the sun had yet come up in its magnificence I was able to see the greenish blue of the hill sides; the purplish green of the rocks; the sandy brown of the river---all dimly suggested in the twilight. There was a chill in the air and a gentle breeze that played with one’s hair and scanty garments until the sun came up and bathed everything in a different hue.

There is an art in the pronunciation of the word Pashoke, as there is in the pronunciation of most words in these regions. The first sound you make is like a splash; the next a noise like a monkey---onk. Though you need not scratch yourself under the arm unless you want to.

A preliminary to departure was the production of the visitor’s book by the chowkidar, a goodly soul whose unkempt condition suggested one of the many beggars we see at the corner of Dharumtollah,---with the difference though of a Mongolian cast of countenance. The entries were interesting. General Chung, the last Chinese Amban in Tibet, spent a night in this very bungalow in May 1913. That was after he had left Tibet for ever and was proceeding---he little knew then---to (so it is whispered) his execution in China. He was, it is stated, blamed for having evacuated Lhasa---when his small garrison did all it could against the hordes of the Tibetans. Along side General Chung’s name were the words “and party, To see Deputy Commissioner.” What was the result of that interview is a closed chapter. Perhaps it was to ask permission for himself and his men to pass through India.

Almost a year later Lady Carnduff resided in the same building; a month later General May, and later still in 1914 is the name of Miss Carmichael. My own added to this worthy collection I proceeded on my journey.

The valley paths were damp and strewn with leaves after the all-night rainfall. In the distance gunpowder boomed with the blasting of rocks and the making of new roads. A fragrance of weeds and simul bark pervaded the air and around was thick jungle as far as the eye could see.

A little way out is a shelter with a three-sided wooden bench, commanding the confluence of the Rungeet and the Tista, and to the right the road descends in irregular puddly stages to the Tista bazaar and the bridge beyond it.

At this bazaar we passed our coolies, who had, after their custom, set out considerably earlier than I did. Outside a tea stall I saw my coolie girl feeding a little one, whom I did not remember seeing on the day previous. It was, I fancied, either borrowed for the occasion or had been concealed somewhere amongst my stores during our marches. Opposite this spot on a bamboo construction were perched three roosters intently engaged in discussing the immodesty of the exhibition.

Beyond the bridge the road stretches away to Melli,---the calling place for breakfast. From this road one can see to the left the first glimpse of Sikhim---a solid mass of greenery. Behind, a spot of white amongst the jungle, is the little bungalow of Pashoke---my house for one night in the vicinity.

The Sirdar spoke as we rode onward to Melli, of the bears and monkeys and the visits these creatures pay to the lonely chowkidar of Pashoke. No wonder the chowkidar appeared to be only half human. No wonder the Sirdar and the coolie women looked so scared that morning.

The day was hot and sweltering as the sun worked patterns upon the trees and people. Butterflies with eyes of a thousand colours upon their wings danced around in front of the horses; and cockchafers made the entire Himalayas resound with their quaint metallic noises, sounds that were only stilled in the increasing swoosh of each approaching waterfall.

At Melli the horses were unsaddled and turned adrift amongst the vegetation to take their little rest while they could get it. My animal rolled himself upon the grass performing a queer feat of backscratching in which he so much delighted that he was loth to leave off for the continuance of my holiday. We had to await the pleasure of His Royal Highness Horse a full half hour, but he was apparently aggrieved at not having been consulted with regard to my excursion. He went round and round the bungalow and it took the combined efforts of the syce, the Sirdar, the chowkidar of the bungalow and one or two villagers to curb his obstinacy. And then we were once more gaily started.

We passed a number of points where the road had been washed away by the previous night’s rainfall, and in one place the land was slowly slipping above the roadway when I was advised to get across quickly lest I should be held up while repairs were in progress. It is surprising though how speedily repair work is undertaken. For there is the rubbish of the hillside to clear away primarily, and then the blasting of rocks in order to widen the path to its previous measure. The road-menders are almost all Lepchas, the aboriginal inhabitants of the country. But strings of Gurkha carters passed me on their way towards Tista, transporting to that station square packages of tea, perforated chests containing Sikhimese flowers, and barrels of milk for the villagers---all responding to the magnetic call of the railway.

At mile 7 we passed a thickly wooded hillside labelled “Bhalukhop.” It is, my guide tells me, the haunt of the Bhalus---the brown bears of the Himalayas. And sometimes, he tells me, these animals descend upon the villagers, whose settlements can be seen far, far above the roadway like little specks amongst the vegetation, reached only by tiny, irregular mountain paths; and upon them the bears wreak an unnecessary vengeance of life and property. Sometimes the white Sahib comes along with a long rifle and then he does for the villagers what their strange gods have so long failed to do. These villagers all worship the white man, and bow in salutation as he rides past.

Not far from the Bhalukhop is a little doorway at the foot of a high rock. Swing this square foot of battered wood forward and a passage of impenetrable darkness will reveal itself. The passage is barely wide enough to admit a man; but there within, many hundred yards within, is a sanctuary of the gods---for it is here, the lamas will tell you, that the great God Sakyamuni, the one and only Lord Buddha, paused for rest on his way to Tibet. From this sanctuary one path leads downwards to the riverside---the river Tista, which is always with you along this road until your next halt for the night; while another path leads miles into the interior emerging somewhere, nobody knows where. It is all concealed in impenetrable darkness; and with the aid of what lights the worshippers reach the sanctuary and what gods actually inhabit such depths of darkness none is able to tell correctly.

Chapter IV

Entering Sikhim

Not far distant was the bungalow of Tarkola, six miles from Rungpo.

The air grew perceptibly hotter. The sunshine was brilliant, almost blinding, and but for the Gurkhas, the alpine vegetation and the sounds of the waterfall and the rushing stream one might easily have been led into believing that he was back again in the plains. Now and again the greenery was broken by a patch of brown rock scarred with the gash of the labourer’s pike.

The air was full of sound and smell; never for a moment was it free of either. The roar of the river was intensified at intervals by the swoosh of the waterfalls as they leapt down the hill-side. The crickets chirped from tree to tree and every now and again there was one in their midst who had learnt in some manner to produce its melody upon two distinctive notes. Such creatures were never slow in displaying their powers; but whether they gave their display for the admiration or envy of the rest of their kind, they certainly had the intense admiration of one member at least of humanity.

My coolie girl was not so cheerful that day. Perhaps it was due to the weather. She and the others passed us while we paused at Melli for breakfast, and now our horses passed them once more nearer Tarkola.

The atmosphere was stifling. Everything---the crickets and the waterfalls excepted---seemed to be charged with a spell of drowsiness, and we crawled dreamily onward. Even our Tibetan ponies were half asleep as they faltered, muttering---as they appeared to do---in a sort of dreamy incantation the “Om mani padme hom” of their country people.

A tired feeling came over me. The rhythmic jog of horseback was inspiring of a sensation of torpor and I nodded until awakened by realising the peril of some spot overtopping a precipice. Then I turned my attention again to guiding my pony.

The vale was a vale of butterflies: butterflies of green and blue; white with deep black swallow tails; yellows without any border; browns with swallow tails of white, and chequered butterflies of blue and black; quaint mauves, and others like clippings from printed muslin; butterflies with wings like leaves; and some of entire saffron like any Brahmin on a pilgrimage.

The road dragged ceaselessly under foot. The mile posts went by slower and slower and all one’s efforts to make the horse trot failed until in time one didn’t even have the energy left to endeavour. There is a secret in persuading Tibetan ponies into quickening their paces and that is in making a sound like sneezing. I did not learn this till afterwards when a symptom of cold produced from me a double effort and set my horse off in an unexpected gallop. Careful observation of sounds since then has taught me that the syces and the Sirdar also produce sounds akin to “Tschoo-Tschoo” if they want the animals to proceed quickly. This is apparently a Tibetan word, the etymology of which I have not endeavoured to study.

Tarkola appeared to be the hottest place in the world. The dak bungalow---a Forest Department construction---showed its teeth of unwelcome in the bare planks that passed for walls in the interior. The Chowkidar was absent, everything was thick with dust and mouldy, and pending the warden’s arrival I had the satisfaction of sitting in the verandah and watching the ponies at lunch while my own, of not so easily procurable a variety, depended on the fire and the kitchen for preparation. From the verandah I could see the forests of Sikhim stretching high up into a mist-capped summit.

The path onward to Rungpo is through forest glades with trees so thick on either side that the river though audible is rarely visible. Now and again the road emerges by the riverside and bursts upon the prettiest of views---brown rocks towering above the water’s edge or the sandy bank sloping down to the green and white ripples.

On the roads the menders work and carts go by, while from the hillsides issue round bellows of smoke---the signposts of the charcoal burner’s industry. Reed mats on lank bamboo supports act as shelters for the road workers, and the brown of a native settlement peers from behind the bushes.

There is not much else to see until one comes to Rungpo. A bridge across the Tista leads into Sikhim, and near its entrance stands a frontier post where a guard or two come forward and demand your passes. A moment or so later you are in Sikhim.

Rungpo is a straggling town by the water’s edge, possessing a Post Office and a live policeman. The bazaar clings around the buildings of the settlement which are ranged on either side of the roadway, and beyond these, up a picturesque path shaded by trees and flower hedges where yellow butterflies frolic in their hundreds, stands the dak bungalow---my home for my first night in Sikhim.

The bungalow is a commodious construction and wholly English in arrangement. It is, if I am not mistaken, still under British care, since the Resident at Gantok’s notices adorn its walls on all sides. There are no mattresses, but the cotton strappings of the nawar bedsteads, eked out with a blanket or two, which the heat of a height of a mere 1,200 feet permits you to discard, serve admirably without them.

Rain fell soon after my arrival at Rungpo, which added to the stupendous noises of the valley. At tea time these were augmented by the slip-slap of the syces grooming the horses and the clamour of the coolies in the kitchen where they were regaling each other with the gossip of the villagers, retailed to them separately during the day time.

I remember during my ride that day to have discovered on passing the coolies that the coolie girl carries her baby behind her in her basket amongst my stores. This I first espied by noticing an exceptionally large onion in the midst of the vegetables, but on fixing my gaze upon it, found scanty locks here and there and soon saw that the object really was the uppermost extreme of a slumbering brown baby.

All through tea the river kept puffing like an enormous steam engine, while in the night time my repose was interrupted by a nasty drain pipe that neglect and rain had caused to drip unceasingly outside my window.

Chapter V

The Capital of Sikhim

The morning was damp and sunless. Rungpo lay before me a small plain ending abruptly at the river, beyond which rose the high hills of British India. The road to Gantok lifts gently off this plain and rises by stages of other plains on to cloud land. Everything bore the brand of cultivation and the fields unfolded grasses of a variety of hues of maturity: Indian corn and maize and the ever favourite murwa---the beverage of the Sikhimese Bhutias.

The methods employed for irrigation were quaintly original. Every waterfall was pressed into service and its powers conveyed by bamboo piping on to the green fields. Bamboos lined the roads on the both sides. Split bamboos with the water trickling through the hollowed surface, ran overhead and poured their contents into others which lowered them gently down to the cultivator.

Settlements of brown thatches appeared in all directions---brown in its varying shades from hut to inhabitants; brown even to their very rags. And the only notes of colour were in the fat hens, the cows and the stray dogs of the villagers.

As we went by the inhabitants all turned out in their numbers to watch our stately procession. Even the hens and dogs ran forward, while the cows looked up from the staid monotony of their occupations. One old hen with an unbounded zeal for processions scuttled forward most hurriedly in her odd manner, and then, slipping on the moist hillside, performed a glide on one leg such as I thought only Charlie Chaplin was capable of doing. She eventually steadied herself by raising the other leg in the air, and, taking a gentle turn to one side, again like the film actor, she stopped. She did not, though, put a wing to her beak and giggle. There was no applause from anybody. Not even the fowls and dogs were interested in her performance.

The road I was climbing was, I was told, constructed at the time of the Younghusband Mission. One party of soldiers went to Tibet through Gantok and the Nathu La; while another proceeded by the straightforward road, via Kalimpong, on to the Jelep La. On one side a little way after we started we saw enormous rocks chock-full of copper---worked, I was told, by some German miner, until claimed for internment. Signs of work were there plentifully manifest; a viaduct across an immense gap and huge cave chambers now sadly neglected. Stones on the wayside were pointed out to me as being riddled with copper. But it was their working that was wanted. Sikhim is really quite rich in this mineral.

In a little while I met my first bird in Sikhim, a pretty though little specimen. As a result of the previous night’s rain many of the waterfalls were very swollen, and difficult to cross where the authorities had not by a bridge safeguarded the travellers from the dangers of the monsoons. The crossing of one such spot where a waterfall had developed into a roaring torrent presented quite a problem which was solved, so far as the coolies were concerned, by the man carrying the women across---on separate trips---on his shoulders. For myself I trusted to the tender mercies of the pony who was fairly sure of footing and got across by stepping on more or less loose stones despite every effort the rushing stream made to dislodge his foot-hold.

Sheep passed me in great flocks driven by Tibetan shepherds, all whistling their shrill notes of warning. The sheep were of the mountain variety and in their rear marched old rams with quaintly twisted horns.

At Singtam, a little beyond the dak bungalow of Sankokhola---where we did not call---the road that leads off the Chowrasta at Darjeeling joins this highway in a common journey to Gantok. The road has come from Temi, through Namchi and the Manjitar bridge, across the Rangit. At Singtam you leave the Tista and follow to its higher course a smaller but far prettier stream.

About mile 16---that is to say 8 from Rungpo---the road deploys upon a beauteous view where bushes of flowers run down to the river’s edge and stoop over with their lips to the water. Butterflies and birds play friendly around, and higher up are the hills, not quite so wooded, but full of signs of life and cultivation. Pumalo groves are around you and the air is filled with the fragrance of the fruit while the roadway is strewn with relics of wayfarers’ repasts off this delicacy. Just here and there a big crag frowns: everything else is so happy, so friendly.

We next came to the bungalow of Shamdong. At the entrance the stump of a tree stands up erect like a stag---an unconscious touch of beauty. For the bungalow itself is very dirty, as is also the Chowkidar, against whom were entered complaints in the bungalow book. These visitors’ books are most interesting narratives. They bear, many of them, the records of personal history, and nearly all tell their tale of broken crockery. This book, however, had as its first entry the following:---

Suggested that the Chowkidar be changed. He is apparently suffering from skin disease. Keeps dogs which stole some our food.

And then below this:---

I find it is the Chowkidar’s brother who did all the work and it is he of whom I am complaining.

The official entry against this was:

Noted. The “brother” who acted for the Chowkidar has been warned not to put in an appearance in future.

But the dog is still there---a black and tan specimen that very nearly succeeded in annexing my foodstuffs.

A mile out of Shamdong is a little tablet by the roadway, placed to the memory of some ill-starred road maker who ended his life whilst employed in his duties, more than 15 years previously. This little slab of stone brought home to me more than the road itself had done before, the peril of road construction in the mountains. It had taken its toll, so far as I knew, of at least one person.

The panorama was still of cultivated fields with occasional glimpses of the river. Here and there a cultivator is visible on his own fields and cows wander amidst the hedges unattended. The new stream that joined us at Singtam, from where the Tista went on northwards, was the Royo Chu---a stream of unending picturesqueness. The road itself was sadly deserted. Relics of carts and wheels littered the sides, and flocks of sheep went by like white fleecy patches. And as I had taught myself to count imaginary sleep as an antidote to insomnia, the effect of watching these passes was every bit drowsy. Each animal had a tiny speck of mud at the end of each little strand of fleece---due no doubt to rolling on some damp spot overnight. They had all come, my guide’s enquiries elicited, from Tibet through the northern passes of Sikhim, and had passed through Thangu, the place which the Governor of Bengal has but recently visited.

A little bridge across the river leads onward to the hill of Gantok. The capital of Sikhim reclines on the summit and the climb upward, especially by the short cut, is most wearying. The bends of the narrow roadway are the most atrocious conceivable. The sensation on horseback by this route is as bad as it would be if one tried to ride up the steps of the monument in Calcutta. Only the latter would not be quite as perilous. The horse performed a variety of circus turns; and as the road narrowed the higher it mounted, I began to fear for my safety. My horse had an objectionable manner of pausing at the sections that were most nerve-racking, as if it were his confirmed intention to cause me to reflect fully upon the dangers that lay before us. Then once more he would stumble forward. One false step and I should be reduced to infinity, after the manner of certain things in school arithmetic. Then a particularly large bit of rock would project just where the road was narrowest and steepest and where the precipice on the other side was deeper than ever. My horse had an antipathy to large rocks and showed it by edging towards the.....! Then he would crane his neck downward and behold the beauties of the country lying far far below him, while I could do nothing but shudder silently.

The journey had indeed been arduous for the animal. Moreover he may have had family troubles of his own to disturb him. The opportunities for suicide were incomparable, and I could only hope he would do nothing with me in his company.

Chapter VI

Round about Gantok

The short cut to Gantok was more tiresome than the main road could possibly have been. I saved four miles by this route, but I was a considerable time saving them. In point of fact I actually timed myself, and, working on the basis that there were 8 miles to do by the cart road, I should have been in Gantok, had I gone by that route, half an hour earlier than I was by the short cut. The explanation is that the horses got out of breath in negotiating the steep inclines, and much time was wasted in pausing for their recovery.

There are in all three actual short cuts, one above the other; the route the rest of the time coincides with the main track. Of these three cuts the first is by far the longest, while the third is almost inconsiderable. When the first has been completed the straggling town of Gantok breaks in upon the vision and is kept in sight practically the whole of the way upward.

The entire run to Gantok was 24 miles by the cart road. The coolies were in consequence left far behind us, and even our syces dropped back until approaching the short cuts when they seemed to have recovered both their breath and their cheerfulness. When the busti below Gantok was visible I could hear them whistle the calls of the Darjeeling police---for the Bhutia boys are adepts at picking up all airs. Numerous rest benches marked the road at intervals and upon these at stages the syces rested, contributing no doubt thereby to the religious merit of the souls of the departed founders.

In the busti referred to were numerous tea shops all briskly frequented. A woman had charge of each of them and exchanged pleasantries with her customers in a manner not known in India. Some wayfarers more pressed for time quaffed the beverage on the roadway, and amongst these I must number my Sirdar who had qualms about keeping me waiting. So taking the enamel glass from the fingers of the maid who served him, he raised it to his lips and almost as soon gargled out its entire contents upon the roadway. This was due, he told me, to its putrid composition. No milk, no sugar and yet three pice! But he dared not say it loudly. We were strangers in a strange place and two Sikhimese youths stood by with sporting rifles, whistling to birds which were never coming. So he paid the three pice without comment and jogged onward to Gantok. The woman, for her part, seemed injured by the insult; but she too held her peace.

The road to Gantok was thronged with traffic. Traders went by us by the score and more flocks and shepherds, till at length we came to a school opposite which was the bazaar wearing a lively appearance as it was market day in Gantok. Most towns in this area hold their market days on Sundays---an incident which I have been unable to account for.

Gantok is a city of toy houses with the cleanest little bazaar in the world. This is probably due to the fact that the old bazaar, which occupied the topmost ridge in Gantok, was destroyed by lightning and a new one has but recently been constructed a little lower on the hill-side. The topmost ridge when I saw it was a dreary waste with promise though of being transformed into a Chowrasta. Tree guards of cane lined it on each side between the Maharajah’s two palaces and the dak bungalow---which occupied opposite ends upon this eminence.

In front of the dak bungalow is the Edward Memorial erected by His late Majesty’s “loving subjects in Sikhim.” This is merely a rest house and women come here as a rule to knit and to gossip. The Sikhimese woman’s love of knitting is unbounded. Possibly it is the weather that makes woollen wear imperative; and with Tibet only across the frontier, wool ought not to be difficult to procure.

The capital of Sikhim, one regrets to say it, is in total darkness at night time. Not a single, solitary light guides the wayfarer in the darkness. There is no electricity in the station, and if any one is misguided enough to venture out after sundown---no Sikhimese subject is---he must carry his own lantern.

I went on to the bungalow. It was already almost dark when I arrived there and found to my surprise the building well stocked with white people. There were two ladies who had just completed the tour that I was about to undertake---to the passes of Tibet; and an American student who had been in Gantok for a number of months engaged in the study of Tibetan.

My coolies were an unconscionable time in arriving---or perhaps it was unconscionable of me to expect their earlier arrival, seeing that the distance traversed since morning was considerable. At any rate the discomfort of not having my things to change into, or even the stores to tackle, was a trifle disconcerting. I got tidy somehow eventually and called on the Maharajah.

I had the good fortune to have been in school with His Highness. Our meeting was in consequence one of the utmost cordiality. His Highness pressed me to stay to dinner, and provided an excellent repast.

The Maharajah is a young man of six and twenty. He succeeded his brother as a ruler in 1914 and is wholly responsible for the help Sikhim has rendered us during war time.

The return from the Palace to the dak bungalow at the late hour of 11-30 was a feat to accomplish in that blinding darkness, despite the aid of the palace servants and lanterns which the Maharajah so kindly provided. Much work in the advancement of the capital of Sikhim has, I understand, been held up owing to the war, and His Highness told me one of the first things he has in mind is the linking up of Gantok with India by railway. The line would in this case be a continuation from Tista, the termination at present of the Kalimpong railway.

At present the Maharajah covers this distance by motor in a Baby Standard. The road down from Gantok is good enough almost all the way to Tista, and amply broad for a Baby Standard. The Maharajah also does a considerable amount of motoring within his capital.

I returned to the dak bungalow, as I have said, at 11-30. None of the servants were sufficiently anxious about me to wait up for my return, but my pony, solicitous of my safety, entered my bed room during the small hours of the morning to see if I was by any chance a-bed, and disturbed me not a little by this act of consideration.

Chapter VII

The Gantok Bazaar

The next morning I was up early to look at the capital. The morning was not very bright and before long it drizzled, but later the sun appeared and the day was in every way promising. The Maharajah has two palaces in Gantok, a big one with a brown roof, and a little white one quite near it. It was the latter in which he received me. The place was very prim and tidy and chock full of Tibetan curios. One section to the right of the porch was most artistically decorated on the outside. This, I learnt later, was the chapel.

In front of this palace is the printing press. As far as I know no papers are published in Gantok, but the press is utilized merely for Government purposes. Opposite the palace are the palace stables, and beyond these the new Secretariat which is now under construction and is, I am told, to be larger than the Secretariat in Darjeeling.

Far behind both palaces is the Maharajah’s carpet factory where girls and women work at the looms and turn out some of the prettiest of articles. The entire palace’s flooring supplies are obtained from their workmanship, and every individual works most assiduously and cheerfully. In this factory I was shown a quaint Tibetan brass lock. It is a clamp-like affair rather intricate in its management and most crude in construction. This one lock suffices, however, to keep out the Gantok brigands---if there are any---from interfering with these preserves of the Maharajah.

But Gantok seems to be good and orderly. The hand of “Pussyfoot” is not yet upon the place, but for all that there is only one “pub” in the whole city, and in this the murwa is quaffed with the quietude of a clerical tea party. Around it are numerous tea shops and one or two restaurants providing light refreshments. In one of the latter I found my party of coolies, who, with the syces, were having a merry time in the company of a number of the Gantok residents.

This was in the bazaar. Around are a number of shops kept by Afghans and Marwaris who sell the trashiest trinkets at the most fabulous of prices. I had run low with some of my provisions and entered a Kabuli establishment to buy some biscuits. The shop-keeper showed me a tin of Jacob’s Cream Crackers for which he wanted Rs. 2-12. I offered him Rs. 2-8; but he merely wailed about the customs charges, the perils of the journey, and the increased cost of living. He next produced some candles at my bidding and declared they were twelve annas a packet.

“Twelve annas and two-twelve make four-eight,” he said quite calmly, “but for your sake, Sahib, I shall reduce the four-annas you have requested and make it four-four.”

If the Afghan thought he could “do” me it is an insult to Calcutta. Two twelve and twelve annas make three-eight and always will, but when I told him so he refused to allow the reduction. The four annas off was not worth while unless he could more than recoup it. The amount paid therefore was three-eight and no reduction.

I was all along during my walk through the bazaar an object of much curiosity. Shop-keepers left their stalls and came out to see me, forgetting to beckon in their astonishment, feeders at restaurants left their tables and men from the “pub” ran out with their glasses. I suppose I created as much sensation in Gantok as a Tibetan would in his national garb in Covent Garden. “Blime, Bill, there’s a funny cuss for yer”---or rather the Sikhimese equivalent at my expense.

In this bazaar there was an old Chinaman---a tailor, with white hair and a pair of spectacles. This is the nearest to Tibet that I have seen a member of this people.

Some beggar women next approached and stuck their tongues out at me. Fortunately I had already heard it said that this with them is a form of salutation; else I might have been unduly offended. But there is a wealth of significance even in the sticking out of the tongue, according to the actions that accompany it: whether the eyes glare wide and a scowl is fashioned, or the head is bowed and wagged submissively from one side to the other. The latter is what the old women did and the impression it conveyed to me was that the women would readily suffer strangling on my behalf. I was glad after that to give them some coppers.

I had my Sikhimese guide with me all that morning. For one thing he knew the city; for another very few people in Gantok speak Hindustani. He next took me to a sort of a Gompa (temple) surrounded by prayer wheels. There was an entire row of them running round the building and we walked right round the place while the Sirdar set every one of them in motion. The idea is apparently that the swing of the wheels creates a breeze and the winds bear the prayer to Heaven. The streamers of cloth and paper that one sees marking the roofs of Tibetan settlements or waving from the summits of mountains are also believed to serve a similar purpose---the breezes wafting the prayers to the Almighty.

Inside, the Gompa was just like any other. An immense prayer wheel on each side of a mighty Buddha and before it, on a table, holy water and burning butter and incense. A little tubby lama advanced to meet us. He had a rosary between his fingers and was repeating to himself the “Om Mani” prayer.

Before I knew where I was, I saw the Sirdar on all fours before me, crawling forward rapidly towards the Buddha. The lama and he exchanged between them certain sounds like the firing of cannons, and then they were ready to direct their attentions towards me.

Lamas, I have found, are very obliging and no part of the temple is too sacred for the gaze of the foreigner. On the walls on each side of the Buddha pigeon hole shelves stretch away to the corners of the chamber. In these are placed the religious books of the lamas---the Kanjur, the Tanjur and the Boom; the books, in which are written all the prophesies.

“And what prophesies are there?” I asked curiously.

“The prophesy of the late war between England and Germany.”

“Indeed. And what is a prophesy of the near future?”

“War between Tibet and China.”

My guide looked concerned, but maintained his silence. Pictures abound in the Gompa, all the handiwork of Tibetan artists. After an examination of these and the conferring of a consideration to the lama---they are ever meek enough to accept this---we took our departure.

That afternoon I called on Dr. Turner, the Civil Surgeon, and in the evening went to tea at the Palace. Mrs. Turner invited me to return to dinner, and the journey there from the Palace at night time in pouring rain and on horseback, was a more difficult task to accomplish than the previous night’s walk in the darkness. However the horse was indispensable as I was already late for dinner. Dr. and Mrs Turner I found to be very hospitable people but they were bowed under a sorrow inflicted upon their home by the late war. Bertie, the fond son of his proud parents, was killed in an aeroplane crash in Central Asia whilst on his way to bomb Astrakhan, a few months after the armistice. Thus had Armageddon penetrated even into this distant solitary white home on the mountain top.

At about 7 the following morning, the weather had sufficiently cleared to give me a glimpse of the snow line, and I was favoured with a view of Kinchenjunga, other than we get in Darjeeling. The range of Kinchenjunga stretches between Gantok and Darjeeling so that the snow-capped summit is seen from Gantok from the opposite angle to the one we get from our holiday hill station of Darjeeling.

Gantok was full of flowers that twinkled in the sunlight, and wild pigs roamed the capital in place of dogs, of which there were very few in number.

Chapter VIII

Life in Gantok

Gantok was, as far as I could gather, once a scene of gaiety. Gaiety such as is got in our hill stations one cannot expect; for our hill stations are primarily holiday resorts with Government business merely as a secondary consideration.

But Gantok, the capital of Sikhim, was at one time, and down to but a year or two recently, inhabited by a band of Europeans---officials in capacity, but social because of their wives and families. The Resident entertained the Civil Surgeon, the State Engineer, and the Assistant to the Maharajah; and later in the week the State Engineer entertained all the others. Then the Maharajah gave a dance and garden party to which the whole station was invited, including of course the Councillors of His Highness, the Kazis, or zemindars, who have a form of petty jurisdiction, the judges of the Chief Court in Gantok, the officers of the regiment, and others. Or if it was the season of worship of the ever-lasting snows when homage is paid to Kinchenjunga, then the station was again entertained by the Maharajah.

The youthful European element, though, turned to Darjeeling for its ordinary gaiety; the older officials had no need to eke out the simplicity of the rounds that were supplied them in Sikhim. The younger rode into Darjeeling on Saturdays for dances at the club and rode back again on Sunday, covering the distance of 60 miles each way during the daylight of one day on each occasion.

Apart from this though Gantok has nothing to offer, its particular elevation encourages cultivation and all the fields around stretch like terraces on the mountain side, studded with settlements as far as the eye can see. The sights of Gantok are seen in one day---and the pretty toy houses with windows rimmed in many colours cease to attract attention in a hardened inhabitant.

But beyond Gantok there are excursions enough for those who seek them. Pamionchi, the largest monastery in Sikhim, lies a little to the north-westward, with its three hundred monks and its “Archbishop of Canterbury” who crowns the Maharajah; Thangu and the northern passes to Tibet, more or less bridle paths most of the way, and with few dak bungalows to afford any shelter. And finally the passes to Tibet. Nearer Thangu, I have been told, there is plentiful shooting, but around Gantok there was at the season of my visit very little even in the way of small game; and the same may be said of the road to Tibet.

The lot of the European in Gantok is also alleviated by the visits of friends, who come but rarely. Tourists too are few, and a perusal of the books in the dak bungalows indicate that not more than an average of a dozen yearly, mostly men, ever travel in these parts. And in connection with these visits excitement is caused by suspicion. A wary eye is kept upon possible spies, and gossip---a real thing even in these parts---will tell you of women spying in the villages, and nearer the frontier; of German lamas who used to traverse the country prior to 1914 and, under the guise of Buddhists, penetrate into the forbidden land, the land of mystery. Scottish Buddhists have also sometimes made their appearance, so it is said, and again it was wondered whether they were really Scottish. There is besides the historic tale of the American that Gantok will always tell you, the American in disguise, who wandered into Tibet from Kashmir, and wandered and wandered till he came upon the British post at Gyantze. And then he was sent back under escort to the frontier and finally back again to his own country. But him they do not accuse of spying; he is merely an American gone mad on touring.

Few Sikhimese speak English. A little bit is heard at the Post Office, and it is spoken in a measure at the Dilkusha, the spacious building beside the dak bungalow, where the State office is housed. English is taught in the higher standards of most schools in Gantok; but instruction is communicated primarily in Hindi and Tibetan.

A Gompa is supposed to have sprung up in Sikhim at every spot upon which Buddha preached, so tradition amongst these peoples has it. Yet it is a surprising thing that Sikhim did not accept Buddhism until the advent of the present dynasty, the Numgyal dynasty which dates back to the days of Queen Elizabeth. The founder of the line came from Eastern Tibet and wrested the kingdom from the aboriginal Lepchas. The present Maharajah is the direct descendant of this line of rulers.

Since the introduction of Buddhism almost the entire State has been converted. But lately there has been a great influx of Nepalese immigrants with the result that Hinduism is vying with Buddhism in its marks upon the country side. Buddhism is, however, the State religion despite the fact that more than half the inhabitants of Sikhim are Gurkhas, who are members of the Hindu faith.

Most Gompas are also Buddhist monastic settlements. There is one such above Gantok, about a mile up the hill-side. Here a number of lamas dwell in different houses, in the interval of tending their flocks in distant Changu, nearer to the Tibetan passes. Above Gantok cultivation ceases. Below Gantok settlements of field workers stretch down almost to the valleys.

But our road was all upward, upward to Karponang---10 miles out of the capital.

We left Gantok rather late in the morning. The road stretched away from the right of the bungalow, then behind it, and climbed in spirals to the monastery, from which an excellent view could be had of the capital. Alongside the temple is the State jail---a line of low, clean buildings.

Gantok can be seen for miles after starting, shrinking into specks on the hill-side with each step away from it. The Maharaja’s palace is the largest thing on the horizon, until it too disappears beyond the vision.

The road so far is good and easy going. At mile 4 the scenery is particularly alluring. The mountain path traces its way through lavish vegetation, leaving the khud line for a lane of hedges and flowers of varied beauty. A mile onward a waterfall appears beside a big cave which acts as dak bungalow to the native travellers. A party was there of men and women from Tibet, with wares for the Sikhimese markets. Bit by bit the road gets more rugged and narrows with the miles onward to Karponang.

The climb upward is also growing steeper. The gradient is now at an angle of no less than 40 degrees---and the road is every bit stony. The fickle path once again leaves the hedges and returns to the khud side which is in many parts unclothed down to the valleys. As the road goes higher, the slope grows steeper and its width ever narrower. Below the khud can be seen the destination of a mistaken footstep.

Gradually a mist descended upon us and blotted out this danger. One was glad of this because of the awful visions depths of such a nature are capable of conjuring up in a fatigued imagination. But the mist turned into rain, and with rain each stone grew slippery. And the slopes of the flat-stones on the roadway were all towards the khud side.

The road was no more than three to four feet across at the widest, and the pony itself was nearly of this measure.

Immense rocks abutted from the hill-side and robbed the traveller of even this little space. Below was a sheer drop to---the Lord knew where. The height of the spot was nearly 9,000 ft.

The path got narrower and narrower and then wound round and round upward; then got steeper, then narrower again and wound round and round above the tree tops which the traveller could see silhouetted in the mist in the distance.

Chapter IX

Karponang

There started from Gantok at the same time as we did a lama and a party of muleteers. They were all proceeding to Changu, the last stop on this side of the Tibetan Passes, where nature provides excellent grazing grounds for cattle. The lama, who belonged to the Enche monastery above the capital, was the proud possessor of a herd of cattle which he grazed in these regions, and one of his duties in connection with this possession was a visit every few months of nineteen miles each way with provisions for the herdsmen---for nowhere beyond Gantok in this direction can anything be grown that could be edible by human beings.

The mules kept well before us, their little bells tinkling with their movement. The lama and one or two muleteers conversed with the Sirdar, and all were in the best of spirits.

When the mist descended and the steep, narrow roadway climbed up to the heavens, with the tremendous precipices on one side, silence befell our little party. I do not know if they mumbled anything---if they did it must have been a little prayer. But the mist came down before us and between us, and the rain beat heavily upon our faces, upon our cheeks, and upon our noses, while leeches dripped from trees to seek what nourishment they could from our necks and ears, and any other exposed parts of our persons.

Every few yards the road bent sharply to the left and a turn to left meant—! One dreaded to think it! Below---was the secret of the mists.

“Here, sahib!” said the Sirdar, dismounting very cautiously, the hand that held the reins showing a slight tremor, “at this spot many a man has fallen below; and many, many mules and horses.”

I shuddered inwardly. It was the fateful mile 8 of which the Maharajah had spoken. “At mile 8”, he had told me, “many a man has slipped over the khud side. The road is not too wide, and very steep. But I am trying to improve it. Perhaps later there will be a wider, and a better road below the present one.”

The road sloped downward for a few yards, with a severe gradient of about 60 degrees. It still wound, and the tinka tonka of the mules’ bells ahead slowed down with the peril, to a solemn t-ink-a, t-onk-a which came to us through the mists ahead.

I dismounted and led my animal. Every step almost was a scrape---the scrape of the iron horse shoe upon the smooth surface of the slippery stones and the procession was a funeral march of what seemed like many hours. Mile 10---Karponang---was never coming. A native dak bungalow was reached at length and the mules and the lama found a shelter from the inclemencies of the weather; while my party plodded onward.

The rain still pattered. A tumble-down wooden structure appeared upon the hill top and I looked to it with longing as a refuge. But “No,” said my Sirdar, “that is not the bungalow. That is a commissariat building---a relic of the late war.”

A few more turns, and then mile 10---yet no dak bungalow; only rain, and mist and slippery stones ahead.

In a little while, though, we found our haven. Wet, hungry and tired, we arrived about tea time. But the coolies, whom I had seen resting in the immense cave at mile 5, were a long way behind us.

The dak bungalow at Karponang stands at an altitude of 9,200 feet and was very cold and uncomfortable. It nestles in a hollow towered over by enormous ugly hill tops that cluster close together. In that dreary rainfall it was the most awe-inspiring spot it has ever been my lot to visit. There is not another busti in sight---no bazaar, no lights.

Some candles were produced, a fire lighted and by the time I got warm I heard the merry laughter of the coolies coming up the roadway. How they could be merry under such conditions I was unable to understand, but if my prayers of thankfulness went up to Heaven that evening the coolies have an excellent future before them.

They arrived at last, and though some minor casualties had occurred in my store basket, I was glad to get something served up by way of a combined tea and dinner. And then for sleep and merry forgetfulness.

“To-morrow’s road,” said the Sirdar, breaking in upon a reverie, “will be worse than to-day’s.” And he was right.

* * *

The road is very deserted. Few people ever come or go by it. The traffic between Gantok and Tibet is only a fraction of that between Tibet and Kalimpong---the main route through the Jelep La. But occasionally one sees a party of muleteers go by and then the sensation of standing up flat against the wall is far from pleasant; but there is no alternative owing to the narrow nature of the pathway.

Not a party though passed us without some inquisitive question from the Sirdar. He wished to know everything about their businesses, down to the ages of their grand-mothers. How different is this from western reserve and western commercial silence. This trader had brought some goods down from Shigatse for sale at Gantok; another was bent on a pilgrimage to the monasteries in Sikhim. They all had their missions and they all told the Sirdar.

The improvement in the weather gave me a chance of having a better look at the lama who, with his mules, rejoined our party in the morning. He was a very different person from the lama described in “Kim” by Kipling. He was young and tall and stately, and did not once mutter over his beads. Nor was he looking for a river, but rather did he seek his herds that grazed at Changu. His lips were tinged with the red of pan and he frequently hummed to himself a Tibetan air. He whistled to the mules in a manner which to them was most intelligible, and he occasionally cursed them too in shrill accents which were far from spiritual. And the Sirdar and he laughed and joked with scandalous familiarity, while even the muleteers occasionally joined in the conversation. There is no class or colour in these mountains, no caste, nor even religious differences. All men are one, except the Sahib and even with him there is a better understanding, better, that is, than in the plains of India.

The road was still steep and narrow. It is not all stone all the way, but mud and loose stones that slip beneath the feet, and the width of the pathway is but two to three feet in most parts with an unfathomable precipice on the right side. Dark scowling rocks overhang the roadway, sometimes offering shelter and sometimes impinging as an obstacle to the tourist. And the gathered rain water came drip, drip, drip from below them in a manner that made one feel it might very easily wear away the stones, which were far from being proverbial.

The road is by no means straightforward. There are barely twenty consecutive yards without a turning. The road curves round boulders, and after every curve one sees the next. The scene in front presents the appearance of some awful hill demon with an ominous scowl, an irregular nose and a protruding underlip. It is this protruding underlip upon which we have to walk, while the lower portions of the irregular nose have to be dodged by the head of the tourist. The paths are very narrow and very steep and for most of the way too, very dangerous. Here and there as a safeguard against danger is a construction of red rhododendron branches that serves as a railing above the precipice. We pass one frail bridge, a slender track above a deep chasm, with fences on each side of red rhododendron branches; but by the time four miles have been covered one has done with danger more or less for the rest of the journey. The auspicious site, mile 14, is marked by a joyous fall by Nature, the finest and the largest waterfall on the entire itinerary.

A curious thing I noticed was that every time we came upon a corner that was particularly perilous some good soul had scribbled on the rocks above it, texts about Christianity, in both English and Tibetan. For my part I mumbled the “Om Mani” as being more likely to propitiate the particular deities of that countryside.

The rest of the road is safe, but not always good. Beyond the waterfall it enters the Changu valley which displays a heath on either side of the roadway. But it is not altogether a picturesque heath. Black boulders litter it on all sides and portions of trunks of felled trees. Here and there the road has been washed away, but the horses scramble up the mountain side with the ease and agility of goats. And all around the cows graze in complacency, their big ugly forms peeping between the deep green flowerless bushes of the rhododendron.

Chapter X

The Nathu La

The Lake of Changu is one of the prettiest sights in Sikhim. It first shows itself to the tourist from Karponang in the form of a waterfall which empties itself at mile 18 into a sort of a miniature stream. Beyond and above this is the lake,---a sheet of calm, unrippled water lying in the hollow and the shadow of the mountains. The road runs by the left in a line of neat white to the bungalow which just misses being on the edge of the lake side.

In front of the bungalow is a barren hollow waste where the lake water possibly comes if it ever rises. The water shows itself in a silver shimmer where the glare of the sunlight falls upon it. For the rest it is dark and motionless.

The scene is one to be remembered. Even the horse paused to gaze upon it---the horse which bears the dignified name of Kazi---or zemindar---just as in America the title of Colonel is bestowed upon people without any offence meant whatsoever. On this lake, I am told, the soldiers of the Younghusband Mission skated in the year 1904 while waiting the pleasure of the minions of the Dalai Lama to come to terms with the powers that be in Simla. Though those who tell the story also add that the skating was not without its casualties, for the waters of the lake are very deep; very, very, deep indeed.

The place was singularly free of mist upon my arrival. The chowkidar told me that it had been raining for days on end previously. But chowkidars usually do say such things in the hope of loosening the purse strings of the tourist at the time of departure. As if the inoffensive chowkidar could help it whether it rained or not. And there is no more sense in giving the chowkidar bucksheesh if it is clear after many dull days, than it would be to give him a hiding were it the only bad day after many good ones. Though he would undoubtedly deserve the latter were he to make the statement of his own volition.

The height of the lake of Changu is 12,600---a height that those who know say is conducive to mountain sickness. Dr. Turner at Gantok had very kindly warned me of this, and had armed me against the eventuality by providing me with some aspirin. This I was advised to take should a headache visit me. For mountain sickness to assume merely the form of a headache is moderate, not to say considerate. Some mountaineers have placed it on record that they, when seized with the sickness, were constrained to roll on the ground and almost bite the dust until the feeling wore off. For myself, the aspirin did the needful, and beyond a slight headache brought on, as I thought, by the severe sun of that particular morning, I was not in any way uneasy. The weather at Changu was weather to glory in. Were Changu not so far, not so difficult of access, and not so inconceivably lonely and desolate, I could hardly recommend a better holiday ground, in season, than the little bungalow by the lake side in delightful Changu.

Not a soul was visible for miles around. The lama left us for his cattle a little before we got to the bungalow, at a spot where cattle grazed in dozens, and where the countryside was dotted by shelters of a temporary nature for the habitation of travellers or the housing of the cowherds. A little before we got to the lake was a canvas erection---a sort of a crude tent which contained a number of women---Tibetan women, whose men folk, if they had any, must have been out with the herds, or doing aught else by the hillside than solace their women. But their women undoubtedly needed no solacing, for they chattered merrily by themselves, indifferent alike to the cattle and their men folk. Above Changu, from the hill behind the bungalow can be seen a great part of the snowy range, and sometimes, in clear weather, far distant Darjeeling. The snows appear to be exceedingly near to the northward; south are Darjeeling and the plains; to the east the Nathu La and the Chumbi Valley. The next morning we started for the Nathu La---the first real gateway to Tibet on my route.

The detour to the Nathu La itself is one of five or six miles from the main road between Changu and Kapup.

The main road resembles in a measure the main road from Karponang to Changu after the passing of the waterfall; that is to say after the perilous tracks have been got over. On this road I met my first yak, a sort of hairy cow of sturdy appearance. These yaks loitered harmlessly on the roadway, but my pony, who if he had ever seen a yak before had forgotten one, took it into his silly head to shy at the ugly animal and skipped backwards off the roadway. I thanked my stars then that this was the first yak I had yet met, for I shuddered to think what my fate would have been had one of these things made its appearance upon the extremely narrow path that I had left behind me.

There was none to keep us company. No lamas, no traders, no cattle herdsmen. We wandered on and on in silence, the chill in the air blunted by the heat of the exercise on horse back and by the enthusiasm aroused by the magnificent heights and depths around us. Presently the road entered an amphitheatre at the opposite end of which on the sky line the Nathu La showed its gate-post heights with the famous pass between them, at an eminence of 14,400 feet. Little lakes sprang into view on many sides, and on the right in the distance could be seen the tiny lake of Kapup and its red-roofed bungalow.

The climb to the Nathu La was almost unending. There isn’t a single mile post to break the monotony of the progress, and although one is buoyed up with the expectation of a glimpse of the forbidden land from the summit, that summit is most distractingly elusive. It is always the one you see just before you and when you have arrived there, it is the next one, and the next---barely fifty yards ahead. It is possible to ride right up to the Nathu La, and one would be well advised to do so. Otherwise one may not have sufficient breath to exclaim over Tibet when one sees it.

Tibet from the top of the Nathu La, hardly presented any difference in appearance from Sikhim as it appeared from the same position. One must understand that although Tibet is a brown windswept tableland one does not see it in this garb from any of the eastern passes of Sikhim. The outlook from there is upon the Chumbi valley which is like unto any other valley one has ever passed, with the exception though that it is rather bare of vegetation and in consequence somewhat brown in appearance.

The valley was when I saw it partially concealed by mist, above which appeared a line of snowy heights from which Chumularhi (23,900 ft.) protruded its triangular apex of solid white in the sunshine. But the clouds in their playful frolicking permitted me as they drifted from one side to the other, to see the Chumbi valley by instalments, and later even rose sufficiently to allow a connected view of the entire valley, with the snow line, though, blotted out of my vision. I was pointed out the positions of Chumbi and Yatung and the Ka-gui Gompa. But I saw none of these places; nor, I am told, are they ever visible from these passes. Not even Phari, which lies at the base of Chumularhi and is hidden by a lower summit.

The top of the Nathu La was absolutely deserted. Not a sign of life was to be seen anywhere, except the Buddhist mound of stones and prayer flags that embellished the frontier, above which a bird flew backwards and forwards a few times.

This was the only guardian of the marches.

Chapter XI

The Jelep La

Not being permitted to enter Tibet---though there was nothing to stop us, except at some miles beyond at Yatung---we had to turn our backs upon the forbidden land and return to the main road that leads to Kapup. The descent was easy, and was accomplished in about half the time it took to go up. The return was by what the Sirdar called a “shawcut,” by which designation he christens any road that is not a proper road. As witness the entire journey from the Jelep La to Kalimpong which was all “shawcut” in the Sirdar’s language. But of this I shall have more to say later. For the present let us plod onward to Kapup.

Another strain of the throat muscles is needed with regard to the pronunciation of the word “Kapup”; but despite all one’s efforts one learns in time that none but a Tibetan or a pigeon can pronounce it correctly. It is “Ka-poop!” with the stress of a ton load upon the second syllable. So to “Ka-poop!” we proceeded.

The scenery before us from the foot of the Nathu La up to the dak bungalow, was almost the grandest on the entire route: such sublime heights; such magnificent depths; such a display of the finest shades of colour; the chilly east wind; growling waterfalls; and the occasional twitter of an unrecognisable mountain bird. The horses seemed to enjoy nothing so much as to sniff the air, and to throw up their heads every little while to gaze upon the splendid clearness of the emerald sky.

Dwarf rhododendron bushes, each like a mass of minute carvings upon billowing green, lined the road on both sides, and an occasional yak showed itself on the hill-side, engaged in the unending occupation that this animal shares with the others of its kind---of chewing the cud. The roads are wider than they have been, and though the precipices are still with us their danger is not so manifest as it was previously. The road is of soft earth, disfigured at intervals by puddles into which the horses splash their hoofs with perceptible delight.

The mountain sides are forested almost to their summits, forested in varying shades of maturity: shades of light brown, dark brown, green and pale green. Flower bushes make a variety with the rhododendrons nearer the road side, their little eyes of blue or pink or white peeping through ever so coyly. And all at a height of 14,000 ft.

The dak bungalow arrived at, the next gateway to Tibet confronts the traveller. The Jelep La stands high on the sky line, but partially visible from the bungalow’s location. From the summit of the Jelep La a stony serpentine track descends to and beyond the bungalow. It leads onward to Kalimpong, stony most of the way, and ever so full of traffic. Opposite the bungalow is a Tibetan inn, the last on this side of the passes.

Kapup bungalow is a relic of the Younghusband Mission. In those days it used to be a portion of a barrack; to-day, it resounds with the exclamations of travellers over the sublimity of mountain grandeur, or with the oaths of officials tired with tedious journeying and inured to mountain beauty. Such are the vicissitudes of a wooden thatch!

The chowkidar came forward after the custom of his kind, with a deep salaam. He too expressed his views upon the weather, past, present and future. Indeed the day was in every way ideal and it was some consolation to feel that the view of Tibet next morning was likely to be unhindered by mist of any sort whatsoever.

Luncheon devoured, I settled down in the verandah with an ancient magazine I found in the place, to enjoy the climate and the story. But I was not left long in my enjoyment of the latter. A panorama was passing before my eyes along the serpentine track to Tibet and it was impossible that I should continue reading. Kazis went by in rich trappings of gold and red velvet; their wives on little ponies, jolted almost out of their reveries; their suite with their bags and baggage, swaying to giddiness upon the backs of tinkling mules, the tails of which swung like pendulums; traders with their loads of wool filling the air with the smell of damp sheep; pilgrims with perpetual frowns and hoary beards, through the hair of which their fingers wandered in uneasy meditation; yak herdsmen; muleteers; and jangling postmen.

The postal service with Tibet is maintained by human runners. The allotted stages, in relays of four, the Gurkha postmen run with bugles and bells, pausing now and again at inns to partake of refreshment. But the inn is more indeed than a postal rest house. Let us go in and see how the Tibetan travels.

A traveller arrives and calls for a cup of tea and a disc or two of flat bread, which in themselves entitle him, should he want it, to a corner of the shelter for the entire night. He unties the band of his long blue dressing gown, allows that garment to extend to its full length, and tucks himself away into it in a corner. If it is summer time he entirely removes that garment, and places it under his head for a pillow; then stretches himself out to full length, his brown arms displayed to view through the looped sleeves of his waistcoat.