The Romance of a Nautch Girl

“There are some things still hidden from the ken of Cook and the race of globe-trotters, and I do not fear to reveal the secrets of this remote corner of the earth, for if any be thereby induced to visit the Peninsula in search of such displays as I have tried to describe, he will meet with disappointment.

“You cannot, in the language of Western culture, put a penny in the slot and set in motion the wheels of this barbarous Eastern figure.”

— Frank Athelstane Swettenham

Chapter 1

A Dark Night

“’Tis past—the mingled dream—though slow and grey

On mead and mountain breaks the dawning day;

Though stormy wreaths of lingering cloud oppress,

Long time the winds that breathe, the rays that bless:

They come, they come, Night’s fitful visions fly

Like autumn leaves, and fade from Fancy’s eye.”

— Ruskin

A light burnt in Dr. Manning’s bungalow. The servant who awaited his master’s coming was in a sound slumber, induced by the poppy-seed, that enriched the evening meal of curry. It mattered little to Ramaswamy whether he slept in the verandah of the bungalow, or in his own particular godown, a small den behind the house.

He was accustomed to the coming and going of his master at all hours; and it caused him no uneasiness nor surprise, when that master failed to put in his appearance at half-past ten that evening.

The small hours of the morning struck, and the night grew darker. A heavy mist blotted out the stars; the air was motionless, and there was absolute silence on the face of nature.

The flying foxes ended their shrieking in the fig trees, where they fought over the red fruit like unholy witches; and they betook themselves to roost on the branches, hanging themselves head downwards. The busy cicalas ceased their whirring mills, and the tree frogs relinquished their persistent cry for “more rain.”

There had been no rain of late, and the dry cotton soil was parched. The carriage drive lay thick in soft pulverised dust, like the dust of dried puff-balls, which deadened the sound of footsteps.

Out of the darkness of the night stepped the Doctor, suddenly and without warning. He was dressed in grey khaki, and was stained with dust to the knees, as though he had walked a long distance. His face wore an anxious, wearied expression; and, as he came up the steps into the verandah, he glanced round, as though in search of someone. His eye fell on the form of the sleeping servant. He stood irresolute for a moment; then, taking up the lamp, he walked into the house, leaving the man to his dreams.

He went straight into his brother’s room. It was empty. The mosquito curtains of the cot were thrown up on to the frame above; the bed was tumbled, as though someone had flung himself on the outside to rest without removing his clothes. On the dressing-table lay a handsome watch, two or three expensive rings, some diamond studs, and a little pile of rupees.

“Silly, thoughtless fellow,” said the Doctor to himself, as he gathered all the valuables together and carried them to his own room, where he put them under lock and key.

After placing the jewels in safety, Dr. Manning went into the dining-room and helped himself to some whiskey. Perhaps it was the dim light of the lamp, or it might have been that his thoughts were not in what he was doing, but there was an unusual recklessness in the way in which he charged his glass with spirit. He added soda-water, and carried the glass into the verandah.

Placing the glass and the lamp on a small table, he flung himself into a cane chair with long arms.

As he lay at full length in the chair—his heels upon the arms—an expression of pain crossed his face, and his brow was puckered with a frown. He lighted a cheroot, and took a long pull at his glass, nearly emptying it. Now and again the cigar was removed from his lips, whilst, lost in thought, he stared into the blackness of the night. Once the cheroot went out altogether, so abstracted did the smoker seem.

But he did not sleep; his brain was far too busy. The keen glance of his dark eyes shot from beneath eyelids that never felt the weight of slumber less than at that moment. Though his limbs rested motionless and still, his mind was crowded with thoughts, which, judging from the expression on his countenance, were not pleasant. A puff of fresh air fanned his face. It was the cool breath of dawn, and it came straight in from the far-distant sea. The warm sandy plain, with its withering cotton plants and its half-baked palms, could not rob that morning breeze of its freshness.

Felix Manning threw away the end of his cheroot, and drew a long draught of the fresh air into his lungs. It cleared his brain; he rose to his feet in all the vigour of manhood, shaking weariness from his limbs and care from his brow, like a young giant in health and strength.

“Get up Ramaswamy and make me some tea,” he said, crossing to where the man lay in deep slumber, and touching him on the shoulder.

The servant stared at him in the bewilderment of waking; and, scrambling to his feet, began to fold his turban round his smooth-shaven head.

“Did Mr. William come in last night?” asked Dr. Manning.

“I do not know, sahib; I will go and see.” Presently he returned.

“No, sahib; Mr. William has not come home.”

“Did he come in and go out again?”

“No, sahib, he left the house when you left; and he went out that way.”

The man pointed in the direction of the engineer’s bungalow.

The Doctor motioned him to go, and turned down the verandah steps into the garden.

The breeze was blowing steadily now, and the leaves were stirring. The fronds of the palms clashed together with a dry rattle, and a soft moan came from the casuarina’s needles. The birds fluttered in their roosting places, and began to chirp and twitter. A faint light shone on the horizon in the East, and the round heads of the palmyras grew distinct against the sky. The cocks in the town crowed to each other and awoke the townspeople. In half an hour the sun would be up, and the little Hindu world would begin the simple labour of the long Indian day.

In a short space of time Dr. Manning heard the rattle of the teacups. The servants knew their master’s weakness for tea in the early morning; and they were also aware that he was never more glad of it than after a long midnight watch by a patient’s bedside. He was a kind and liberal master; and though it is said that gratitude is an unknown quality in India, the men and women who served him never spared themselves where his immediate comfort was concerned. So they now busied themselves in preparing first the tea, and then that chiefest of all luxuries in the tropics, the bath, knowing that it would be the next thing demanded. It was with keen pleasure that Dr. Manning took his plunge in the sparkling water, freshly drawn from the well.

The hideous nightmares of the black night vanished under the crystal drops; the dust and fever were washed from his skin; the frown left his brow, and the lines of care faded from his face, as he tossed the refreshing streams over himself with boyish zest.

It was a handsome face, with large regular features, pale complexion, and dark crisp hair.

He was half through his toilette when a messenger came running to the house. Miss Holdsworth was ill, and the Doctor was entreated to come at once. Ramaswamy delivered the message through the closed door of the dressing-room. Hitherto, Dr. Manning had proceeded in a leisurely fashion, lingering with a sense of luxury in the cool, limpid water, and by no means hurrying himself over his dressing. On hearing the message his manner changed from comfortable ease to impetuous haste, and he finished his toilette scarcely heeding what he put on.

As he rushed from his room, his servant asked him some trivial question about breakfast. He pushed him aside with a gesture of impatience, seized his hat and walked off in the direction of the engineer’s bungalow.

Mrs. Holdsworth met him at the door.

“My daughter is not at all well. She has been in hysterics—a most unusual thing with her—and she is very feverish. I think she is wandering in her mind, for she talks so wildly. The sun must have affected her.”

Dr. Manning said nothing; he followed the kind-hearted but not very intelligent lady to her daughter’s room.

Miss Holdsworth was moaning. As the Doctor came into the room, she started up, as though she would have sprung from her bed, and gazed at him with terror-stricken eyes. He was prompt in action. He pushed her gently but firmly back, smoothed her pillow, rearranged the coverlet, and spoke a few soothing words. She felt the influence of a stronger and calmer mind upon hers, and would have replied, but he checked her decisively,—

“Do not speak; keep quite quiet and control yourself.”

“Yes, darling, you must not excite yourself; you have had bad dreams, and a disturbed night from those dreadful tomtoms,” said Mrs. Holdsworth; “but they are all gone now. I wish, Dr. Manning, we could put a stop to those horrible devil-dancings. Did you hear the noise the people made last night? It was disgraceful.”

The girl writhed as her mother spoke; her eyes filled with tears, and she cast a wild look of entreaty at the Doctor.

“Mrs. Holdsworth, will you kindly bring me a little brandy? or, better still, have you any champagne?”

“Yes; she had some champagne in the storeroom; she must find her keys and then she would get it. He told her there was no need to hurry.

“If you leave your daughter to me for a few minutes she will soon grow calm, and then a glass of champagne with something to eat will be most beneficial. Go with your mistress,” he said to the ayah, who stood watching with female curiosity all that was passing.

For one second the woman hesitated, but he spoke again and she vanished. As the screen door closed on Mrs. Holdsworth and the ayah, the Doctor’s manner changed entirely. He took the girl’s hands in his own firm grasp, and said,—

“Now, Beryl, this will not do at all. You must not give way like this; it is abject folly, and can only get you into trouble.”

The use of the Christian name, and the decisive manner, had the desired effect of preventing tears. She gave a gasping sob or two, and then was quiet. Presently her lips moved in a whisper. He leaned forward and listened, still retaining her hand.

“Oh! nonsense; it is all right. What do you fear?” he asked almost roughly, for the look of terror in her eyes disturbed him. “There is nothing to fear but your own folly in behaving like this. You want food and wine, for you are thoroughly exhausted. Have you had any breakfast?” She shook her head. There was some eau-de-Cologne upon the table; saturating a handkerchief with the spirit, he bathed her hot temples. Before she could say more the ayah returned, bringing a champagne glass.

The woman had been in Mrs. Holdsworth’s service many years, and had nursed Beryl when she was a baby. She was devoted to her, and loved her more than her own offspring. She was therefore a privileged servant, and she seemed inclined to exercise that privilege on the present occasion. Coming to the Doctor’s side, she said,—

“Missy playing tennis too long in the sun yesterday.”

Dr. Manning took no notice of her, but continued bathing his patient’s forehead. The ayah kept her watchful eye on her, and remarked,—

“Missy home very late last night.”

He turned sharply, and rose from his chair by the bed. He took the woman by the arm, and half led, half pushed her into the dressing-room, closing the door behind him, There he spoke to her in her own language. As he talked, her dusky skin paled into sickly yellow ochre shades with fear. He was about to return to the bedroom, when his glance fell on a brown cotton dress hanging over a chair. It was tumbled and torn, a mere wreck of its former self. He grasped it hastily and turned it over, exposing as he did so a great stain. The ayahs eyes met his for one moment, and then fastened again on the dress. Without further hesitation the doctor took a pair of scissors from the dressing-table, and deliberately cut out the stained portion, thrusting it deep into his pocket. He turned the garment round once or twice, searching closely for other spots, but there were none. He flung the dress to the ayah.

“Put it away out of sight, and say nothing.”

And with swift steps he returned to the bedroom. Miss Holdsworth was lying just as he left her. She was calmer, and the wild distraught look was passing from her face. Whatever were her sentiments towards the Doctor, his presence had the effect of lifting the cloud. Mrs. Holdsworth entered the room just as he had reseated himself. She carried some dry toast, and a pint bottle of champagne, which she handed to him to open. He gave Beryl a glass. The slender white hand shook as it grasped the thin stem, but she sipped the wine eagerly. Her mother did most of the talking.

“Do you think it was the sun that affected her, Doctor? Or has she been doing too much lately? When I first saw her this morning she talked quite wildly. Poor child! she was so excited yesterday over the pooja of the people; your brother was telling her about their devil-dancings and all that nonsense. She was at Mrs. Leigh’s last evening; I did not go, as I had one of my dreadful headaches. Mrs. Leigh was good enough to say that she would look after her, and send her home with a safe escort. Ayah, you walked home with Missy; what time did you get in? not very late, I hope?”

The Doctor looked at the ayah.

“Not very late,” repeated the woman. “Missy very tired; went to bed soon, and I did not see the time.”

“Were you at Mrs. Leigh’s, Dr. Manning?”

“Yes, I was there with my brother. I think everybody in the station was there except yourself, Mrs. Holdsworth. We had plenty of music, and it was a very pleasant evening.”

“Was the new Superintendent of Police there; Major Brett, I think they call him? “

“No;—but, Mrs. Holdsworth, I am afraid I must forbid talking: it is too much for my patient. I will write a prescription, and Miss Holdsworth must try to sleep after taking the medicine. I shall look in this afternoon, when I hope I shall find her much better.”

He gave a few directions to the ayah and left the room, satisfied that Beryl had regained her self-control. All she needed now was rest and perfect quiet.

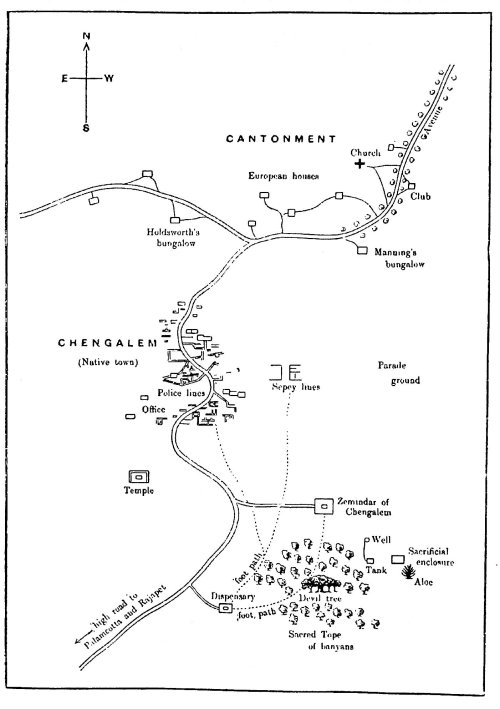

Dr. Manning hurried over his breakfast, for he was a busy man, and all the work of the day was before him. Besides seeing his patients, European and native, he had to drive to a dispensary, and he had to visit a hospital two miles distant in the opposite direction. He was the Civil Surgeon of Chengalem, in the Tinnevelly district in South India.

Felix Manning, F.R.C.S., M.D., and his brother lived together; the two men were said to be devoted to one another. They had both been born in the country. Felix had been sent home early in life to a public school in England. He had done well in following the medical profession; success had attended his studies, and he had taken high honours. He loved his work, and was held to be one of the cleverest doctors in the South. It was a good appointment, as there was a great deal of private practice to be had amongst the richer natives; and for this he was eminently suited, as he knew the language thoroughly, and understood the character of the people.

His father, a staff-corps colonel, married a second wife in India after the death of Felix’s mother; and this lady, though of English extraction, had never been to England. She had money and land, and but one child to inherit it. William was the idol of her heart. In vain did Colonel Manning beg that the boy might be sent home to a public school like his brother. It was waste of words, and a trial to his temper. In despair he abandoned his scheme of education, and left the mother to do as she liked with the child. The natural consequence was that she spoilt him. After her death he inherited her property, and at the age of eighteen he found himself his own master.

Will’s amiability and gentleness made him liked wherever he went; but he was wilful, and impatient at anything like control. He never put himself into transports of rage; but he gave way to a feeble fretfulness, which annoyed his brother almost more than a burst of honest fiery wrath.

From childhood Will was devoted to Felix. When he was a boy he had a kind of hero-worship for the absent brother, who did such wonderful things at cricket and football in that far-away English school. And he always declared that when Felix returned to India he would make his home with him, wherever Government sent him. When he came to manhood’s estate this was duly carried out; and for some time past that home had been at Chengalem, whither Government had ordered Felix.

Much as the brothers loved each other, it must be admitted that the younger tried the elder occasionally. Although the lad was twenty-two, he often acted with the thoughtlessness of a schoolboy. He had an impulsive nature, which plunged him headlong into difficulties of all kinds. The possession of wealth gave him the means of satisfying every whim.

He had no profession nor regular employment to develop the manhood in him; and whilst Felix was working hard, Will was idling the day away, lolling in an arm-chair in the verandah, or hovering round the ladies of the station. He was fond of his horses, and possessed good ones, but he did not care much about riding. He was too indolent. Felix kept them in exercise by using them on his daily rounds; and to him also fell the care of the stable. Flowers were another of the lad’s weaknesses. Wherever he went he must have a garden. But as for seeing after it, or keeping the gang of gardeners up to their work, it was far too much trouble. To Felix he went for help and advice, always finishing with,—

“Do see about it, old fellow. Those lazy chaps will work for you, but they will not do a stroke for me.”

So the elder brother found time to superintend the garden as well as the stable; and Will was always able to lend a horse, or send a bouquet of flowers to his lady friends.

Of late things had not gone so smoothly with the brothers. A new Government engineer had come to the station to look after the roads and bridges, and to keep the precious water-reservoirs in order. He had brought with him the kindest-hearted, simplest of wives, and the prettiest of daughters. Needless to say, everybody in that little station was more or less in love with Beryl Holdsworth. Girls are still scarce in Indian up-country stations, and a young and pretty maiden, with the English roses still in her cheeks, may yet reign as queen in such a place as the cantonment of Chengalem. William Manning fell a victim to her charms from the very first. He sent her flowers enough to fill the bungalow; and although he already had more horses than he knew what to do with, none was good enough for Beryl. So he bought another, a perfect little Arab, which he kept entirely for her own use.

As for Beryl, she was naturally charmed with her little realm.

There was Bankside, the sub-collector, a man of brain and power, who had commanded success from the time that he won his first scholarship. It pleased him to give that mighty brain of his a rest now and then, when he found himself at Beryl’s side, and to descend to the femininities of a sweet woman.

Bankside could not make up his mind to propose. He wanted to save money, and he knew that the nest-egg would cease growing the moment he took domestic responsibilities upon himself. So he contented himself with fluttering round the candle, very nearly as safe as a salamander, with such a head as he possessed to guard his heart.

Then there was O’Brien, the manager and half-owner of the cotton press. He was a warm-hearted impulsive Irishman, with a weakness for photography; and that weakness increased after he became acquainted with Beryl, who good-naturedly sat for him on an average of about once a week. He was always developing or printing her; and he seemed almost as happy shut up in the darkroom with her negative, as he would have been with the original. He was under the impression that he had proposed to her almost as frequently as he had photographed her. But Beryl did not choose to take a declaration of love as a proposal of marriage; and so she kept him at arms’ length, smiled at him, thanked him in her sweetest way for his photographs, and nearly drove the poor fellow mad.

There were others outside the station who came in occasionally; they showed signs of capitulation; but, fortunately for them, the exigencies of the service required their presence elsewhere, before they were totally subjugated, and they never got beyond ardent admiration.

The man who prospered best was the idle boy of the place, William Manning. He had the advantage of both time and opportunity. He also had a long purse, and if he could not command her love, at least he could evoke her gratitude. He showed great delicacy in ministering to her needs. He rarely asked her to accept anything as a gift. The new books and music were always lent; even the piano, brought with some trouble and cost from Madras, was lent in such a way that Mrs. Holdsworth imagined she was conferring a favour on the young man by allowing the instrument to stand in her room. The horses wanted exercise, and Beryl was taught to believe that she was doing a charitable action in taking them out. Will did not inflict his company as an escort each time. He would offer O’Brien a mount, and send him out with Miss Holdsworth as often as he went himself. The utmost he did on these occasions was to ride out and meet her. A few words were exchanged, and he passed on without a sign of jealousy or annoyance. He knew that O’Brien would have to go to the office at ten, and that he would be out of the way till five or six in the evening, leaving the field open for himself all the long day. He could therefore well afford to be generous to his rivals.

What Felix Manning’s feelings towards her were, remained a mystery to Beryl. He showed her some attention when the brother was not there to come between them; but more frequently Will was present, and Felix allowed him—almost encouraged him—to take the foremost place. And this was done without any sign of annoyance at being supplanted by his younger brother. Beryl came very near to being irritated at the ease with which the elder man let himself be pushed into the background by the younger.

Dr. Manning was the only person who inspired anything like awe in her mind; she often had an uncomfortable feeling of inferiority, when she was replying lightly or flippantly in his hearing to some of Will’s nonsense, and she would turn with half an apology to the Doctor. Then he would fix his dark eyes upon her fair face with something more than idle attention, making her feel that he was weighing her in the balance, and possibly judging her severely. She was acutely conscious of her failings, and in her innermost heart she feared the verdict.

But she had no need to fear. He was only wondering what kind of wife she would make—for Will, of course. Would she be loving and forbearing? Would she be able to bear with his folly and childishness? How soon would she tire of his gentle inanities, and long for a stronger manhood to lean upon? She was not one of those independent natures, the special product of the present day, needing no moral support, and preferring to stand alone. She could never become independent, and her life would be ruined if her husband failed her, or, worse still, only roused her contempt. Then his thoughts would wander further afield, where the clinging woman found what she needed in the new brother—the brother who was already Will’s guide and moral support.

But Beryl had no notion that this was passing through Felix’s brain, when she felt his gaze upon her. The colour mounted to her cheeks, and the light came into her eyes through apprehension; and Felix, as he watched, thought that she was the fairest woman he had ever seen.

Things had gone on in this way for some time. Will had proposed; and Beryl, with the perversity of a young girl, refused to take it seriously, and when he had begged and entreated, she bade him wait, and ask again later on.

At first he rebelled, and he made a valiant attempt to pose as a miserable disappointed lover. But with his light sunny nature it was impossible to figure long as the heart-broken rejected one, especially as no restriction was placed upon his visits. Beryl borrowed his books and his horses just the same; and thanked him for his flowers as sweetly as ever. So Will slipped into that happy position of favoured suitor, without being trammelled by a formal engagement, and he found it exactly to his mind. When the season came that he might have spoken, he did not do so; he was content to let matters go on as they were, and desired nothing more. Neither was Beryl at all anxious to bring things to a crisis. She was in love with his admiration, and with his power of gratifying her fancies. But it was a mere shadow of the real thing; the passion of love had never yet shaken her soul; she knew nothing about it; she was a veritable child amongst her admirers; and Felix wondered more than once whether that passion would ever be awakened in her breast. It was time, he thought, that Will should attempt it. A few days before Miss Holdsworth’s sudden indisposition, he spoke to his brother on the subject, and was astonished to find that the boy evaded it.

“Come, Will, tell me the truth; are you really in love with Miss Holdsworth?”

“Of course I am,” he replied impatiently. “Any one can see that, and she knows it, too.”

“Then why do you not try to bring about the engagement? You cannot go on fooling like this for ever, in a sort of dog-in-the-manger way. It is pretty well known that you two are in love with each other. Both Bankside and O’Brien have thrown up the sponge, well aware that it was useless for them to go on with it whilst you were in the field. Go in like a man and win.”

“I like to take my own time about it,” said Will, shifting uneasily in his chair. He did not relish this cross-questioning at all.

“You have been long enough, in all conscience,” replied the other.

“She told me to wait, and I am only taking her at her word.”

“Pooh! A girl should never be taken at her word in matters of love, especially where the ‘no’ was so half-hearted.”

“I am young to be married——”

But at this the elder man burst into a laugh. It really was amusing to hear such a sentiment from one who had been a man ever since he was seventeen. The climate of the tropics develops the human being physically much quicker than the temperate climate of Europe; and five years ago Will had to all appearance reached manhood’s estate.

The laugh irritated him.

“Well! I will not be bullied into it; I will not ask her to marry me at all, if you try to force me.”

He raised his voice in that querulous fretful tone, which Felix found so trying, and which gave the impression to those who chanced to hear it, that the brothers were quarrelling.

“Then you must withdraw, if you do not mean to carry the thing through. It is iniquitous to act in that fashion to a girl, and an amiable, pretty girl too. As long as you hang about her, it is not likely that anyone else will come forward. If I did not know it to be impossible in a remote station like this, I should say that you had seen someone else, and that you had two strings to your bow.”

The words, spoken without any hidden meaning, had a curious effect on the hearer. He started up from his chair, flung his cheroot away, and paced angrily up and down the verandah, where this conversation took place.

“You have no right to say such a thing. You think that because I am your younger brother you can talk to me as you choose, but you are wrong. I will not stand it. You accuse me of fickleness, when you know that Miss Holdsworth is the only girl in the world that I can marry. What chance has a fellow of being fickle in such an out-of-the-way hole as this?”

“Then why get so angry?” asked Felix, surprised at the unnecessary wrath displayed.

His brother made no reply, but left him abruptly; and Felix did not see him again till the evening, when he appeared to have recovered himself.

After this, Dr. Manning looked each day for the announcement of the engagement, but none came.

Chapter II

Missing

“. . . a clot of warmer dust,

Mix’d with cunning sparks of hell.”

— Tennyson

Chengalem was a town inhabited chiefly by ryots and toddy-drawers. On one side of it was the English cantonment, where the European community lived. On the other side of the town, standing apart from it, was the temple. A little distance further on there was a dispensary, which was supported by the Zemindar for the benefit of his ryots or cultivators. Once a year the Zemindar went up to Madras, and lived in state for a few weeks, like a small rajah, with a numerous following of poor relations and servants. He showed himself on all public occasions, and brought himself before the notice of the powers that be, by making a munificent donation to one of the public charities. The wife of his Excellency was in consequence gracious, and the Zemindar, flattered and ambitious for honours in the future, eagerly fell in with her schemes of philanthropy.

The dispensary was the outcome of several personal interviews, which were extremely gratifying to the Zemindar’s vanity. Quarterly reports of the dispensary and its work were sent in to the great lady, with a letter written by the Zemindar himself in flowery language. She replied graciously, under the impression that she was elevating the native mind. She honestly thought him a good man, kind to his dependents, regular in the performance of his social duties, an ornament to the society in which he moved. She had never seen him anywhere excepting in Madras, and she took him as she thought she found him. After all it was best so; it is a mistake to lift the purdah too high. We cannot understand, we cannot reform, the growth of long ages in one short life-time. We may reckon ourselves happy if we can believe, like her excellent Excellency, that we are making an impression for good on the surface of the inscrutable Hindu nature.

The dispensary came under the supervision of the Civil Surgeon. It was a good building, with two or three wards for in-patients, a large surgery, and a comfortable consulting-room for the doctor. It was not often that there were any patients in the wards. The natives had an aversion to the light airy rooms, and preferred to huddle themselves in dark corners of their own crowded huts. The Doctor, knowing their nature, let them have their own way as much as he could. He went to see them in their stifling dens, and thus taught them to consult him freely and without fear. In this way he was able to save life and check disease; because, having won their confidence, the people sent for him at once, before the disease was past curing. If there was a critical case, he stayed at the dispensary all night to be near the patient. He never spared himself.

He learnt many things from that motley crowd that awaited him daily in the broad verandah. Some were told to him; but, for the most part, it was from the chatter of the women to each other, that he gathered information. The uneducated natives have no reserve. Their tongues wag like the leaves of the peepul-tree, telling abroad all they see and all they know. But the Doctor’s patients did not know everything. The temple had its dark mysterious secrets known only to the poojaries, and the dasis or dancing-girls. The Zemindar’s house also had its secrets; they were shared by the band of poor relations and servants who lived on his charity beneath his roof. The Doctor, too, had his secrets, so the people said; and he kept them in queer shaped cases, lined with velvet or satin. A little devil lived in each of the things hidden away in those cases, a dangerous little devil that only the Doctor could control.

The day after his conversation with Will, Felix had occasion to alter the customary arrangement of going over to the dispensary in the morning. A note from the apothecary asked him to come in the early part of the afternoon, to see a member of the Zemindar’s household. There was a difficulty about the woman getting away at any other time; and for some reason or other, she did not wish the Doctor to attend her at her own house.

He accordingly ordered his horse to be ready directly after lunch, foregoing, with some regret, that hour of ease in the early afternoon, generally passed in the armchair with cheroot and book. Will was not at home; lunching probably, his brother thought, with the Holdsworths.

The sun was very hot as he galloped through the town, and a column of dust rose with him as he went. He passed midway between the temple and the Zemindar’s house. Leaving a large tope of banyan trees on the left, he took a bee-line across the open country for the dispensary.

The woman was there in a dooly awaiting his coming. She was too ill to walk, or even stand. The Doctor knelt down beside her, putting several questions to her as he felt her pulse. She gazed anxiously into his face; something was on her mind, and a few queries brought it all out. She feared she was being poisoned. She was sure that Minachee’s mother was slowly killing her. The Zemindar had told Minachee that she must go to make room for a younger temple girl. Minachee did not mind in the least; but her mother, who was a wicked woman was angry, because she, too, would have to leave the Zemindar’s house with her daughter.

“But why do you imagine that she wants to kill you?” asked the Doctor.

“Because I laughed, and said that I was glad she was going.”

“Are you the Zemindar’s wife?”

“I am his second wife; but alas! because I have no son, my voice may not be heard in the house. No one will protect me from that evil woman’s wickedness.”

She began to weep, and Dr. Manning did his best to soothe her. He assured her again and again that her symptoms were not those of poisoning. If she would follow his directions, he could cure her in a few days. The poor thing was not easily convinced. She drew her rich silk cloth around her, and laid herself down on her cushions in abject misery. Life for her was a dreary blank, because she had no son; yet, for all that, she did not wish to be poisoned. The first wife, a proud mother, lorded it over her, and taunted her with her barrenness. It was of no use to appeal to the common husband. He had washed his hands of the two middle-aged women long ago, and was occupied in anticipating the charms of the new dancing-girl, who, in response to a liberal donation to the temple, was to be sent shortly to live in the zenana.

Felix made up some medicine in the surgery, and putting on his sun-hat, he signed to the bearers to take up the palanquin.

“I am coming to the house with you; only to the door,” he added, as he noted her look of alarm. “If Minachee’s mother sees that the Doctor is attending you, she will not dare to poison you. She will be afraid that I shall find it out.”

An expression of childish satisfaction crossed her face. He had hit on the right method of reassuring her. He was pleased with the result, as he knew that an easy mind would do as much good as his medicines.

He rode in front of the dooly at a walking pace.

The Zemindar’s house was between the dispensary and the town, and the way to it lay through a tope or grove of banyan trees. The sun was still high in the heavens; so, instead of skirting the tope by a path that ran outside, Dr. Manning took one not so well beaten, which led straight through. The huge trees, with their forest of stems and lace-work of long arms and foliage over-head, made a pleasant and most acceptable shade to the Doctor. But the bearers were of a different opinion.

In the centre of the grove there was a single giant among giants. Its enormous trunk was hollow, and its limbs—each a mighty tree in itself—were supported on separate stems, each worthy of being called a forest tree. This monarch of the tope was the familiar haunt of an evil spirit—a troublesome demon, given to setting houses on fire, and drinking the reservoirs dry. It was well known to the bearers that he had been particularly annoying of late. He had been throwing stones at the Zemindar’s house, and he had set three huts on fire just outside the town. It was sheer madness to pass beneath his tree.

But a look and a word from the Doctor overcame their scruples. Such a man as he was, holding life and death in his hand, might perhaps defy the devil. On his head be the consequences! Surely the swami would know that the bearers came by the will of another, under whose feet they were but as dust. So they entered the tope, treading softly in superstitious awe. The hoofs of the horse fell with a muffled sound on the dry leafy soil, as though the creature, too, trod delicately in the presence of the malignant demon.

At the foot of the trunk was a low broad platform, which served as an altar. A black devil-stone stood upon it, leaning against the tree. It was as shapeless and crude as the hand of nature had left it. The altar was smeared with red pigment daubed on in stripes. It indicated the blood that delighted the heart of the demon. He had horrid tastes and a voracious appetite; and he loved the blood of goats. He ordered his votaries to drink much toddy, and to eat largely of the savoury curries made of the goat’s flesh, at least, so said the poojaries, who ministered to him, and performed the ritual before his stone. The bearers shuddered as they approached the tree, and thought that it boded no good to the sick woman to be carried beneath those branches.

The Doctor’s thoughts were far away. He was thinking of his brother and Beryl. As he rode round one of the lesser trunks of the giant tree, those thoughts were scattered to the winds by the sight of Minachee, the dancing-girl. The colour rushed to his brow as he caught a glimpse of a retreating figure stepping behind one of the banyan stems.

He pulled up his horse, and looked wrathfully at the vision before him of beautiful womanhood. She was one of the loveliest of Hindustan’s daughters, a dream of soft southern beauty. The girl’s lips were parted with a saucy, defiant smile, and she showed a perfect set of nature’s pearls in her pomegranate mouth. From her brown eyes, as they rested on his face, there blazed forth the woman’s admiration for the man. Whatever the Doctor’s sentiments might be, the unexpected meeting was not distasteful to her, though for the moment it had been embarrassing. She knew the Doctor well, and had often waited amongst the crowd at the dispensary to consult him about some fancied ailment. He had always treated her with the indulgence shown to a spoilt child. Never had she seen him with such a frown upon his face as at the present moment.

Still she was not altogether abashed. Swiftly she approached him, the checkered sunlight flecking her delicate brown skin with golden tints, and, kissing the tips of her fingers, she lightly laid the kiss on the foot that rested in the stirrup. The action was indescribably graceful. It was done with a mixture of the abandonment of the savage and the simplicity of the child, which bespoke the instinctive Circe. The Doctor took it to be a sign that she wished to dispel his just anger, and ask his pardon. His face grew even graver than before, and he neither spoke nor smiled.

With a gesture of fear, which was half-real, half0assumed, she retreated behind the trunk of a tree. Without turning to look back at that saucy face, which peeped alluringly at him, he rode on with pain and anger at his heart, and a vague dread filling his mind.

When he reached the Zemindar’s house, he dismounted, and tenderly helped the sick woman to rise from the palanquin. They had halted at a side-door leading into the zenana. The Hindu women in the south are not gosha (or hidden), and though they may not receive visits from the opposite sex, nor in any way mix with them, they are not afraid of being seen. A knock at the door brought several women out, full of idle curiosity to stare at the Doctor and his patient. He would have carried her to her room, but he was not allowed to do such a thing. All that he could do was to see that she was properly supported by two of her women. She was taken down a dark, airless passage out of his sight.

The Zemindar’s first wife was amongst the women who greeted them. Dr. Manning gave her a few directions as to the treatment of his patient. She listened indifferently, as though it mattered little to her whether her companion lived or died. But something in the Doctor’s manner roused her into action, and she called one of the women out of the crowd.

“Tell her what you want,” she said carelessly.

Guessing that the person indicated was one of the attendants or relatives of the second wife, he repeated his directions.

“I will come here to-morrow to see her,” he said.

“She will come to you there,” replied the first wife, pointing in the direction of the dispensary.

“She is not fit to go out,” he said.

The woman shrugged her shoulders.

“She can come when she is better.”

And with that he had to be content. He mounted his horse and rode away, the women watching him as he went. Alone in the glory of the sunset, his brow lowered again, and an expression of pain settled on his face. He let his horse walk, and took no heed of the gorgeous sky.

“What an ass the boy is to fool round that girl! No good can come of meddling with such women. I must talk to him.”

That evening there were words between the brothers. Felix spoke out more plainly than he had ever spoken before, and Will for once in his life put himself in a violent passion.

It was soon after this conversation that the Doctor was called to attend Miss Holdsworth; and Will, for some reason or other, absented himself from the house the whole of the previous night, failing to put in an appearance with the morning, as we have already seen.

After paying Miss Holdsworth the professional visit, and prescribing for her very unusual attack of nerves, Dr. Manning returned to his bungalow to eat a hasty breakfast. He then started on his morning round, going to the dispensary as usual. The Zemindar’s sick wife was there in her dooly. She was getting better, for she was satisfied at last that Minachee’s mother, Deva, was not trying to poison her. She was well enough to sit up, and listen to the chatter that was going on around her. There was the customary little crowd of women and children, with a sprinkling of men. The Doctor could hear by their tones that something out of the common had taken place. He listened; they were talking of the devil-dance of the night before. It had been a great success. Wonderful to relate, the demon himself had appeared, like a flying fox, with fiery eyes. Every time the awful apparition was described some addition was made, till it bade fair to be a monster dragon by the evening. The Doctor asked one of his patients if Minachee was present at the dance, and he was told that she was not; but her mother was there. He knew that it was not customary for the dancing-girls to take part in such functions, although curiosity might bring them as sightseers. It was mid-day before Felix reached home. He galloped up to the house, and was met at the entrance by Will’s servant.

“The sahib has not come back,” said the man, using his own language.

Felix very rarely spoke English to the natives, and he had taught the servants to address him in their own tongue.

“Is there no letter for me?”

“None, sahib.”

Felix said nothing more, but passed on to his room. The man followed him.

“Shall I go and look for Mr. Manning?”

“By all means,” replied Felix.

“Where shall I go?” he asked.

This is the native all over; he can make a suggestion, but he cannot carry it out without a leader.

“Wherever you think he is likely to be. Go and ask at Mr. O’Brien’s house if they have seen him, Then there is the sub-collector; he is out in camp. Mr. William may have gone to him.”

“Mr. William took no horse, and the collector’s camp is ten miles away.”

“Still, he may have walked out in the cool of the night. Send a syce to inquire; and tell Mootoo to saddle the grey for me.”

Felix Manning strode on, and once again sought his brother’s bedroom. The bed had been made; the toilette table had been rearranged and dusted. Some clean clothes were hung out ready for the master’s return; and the bath was full of clear, limpid water. Felix searched the room afresh, looking into the dressing-case and the drawers. He opened the wardrobe, and examined the clothes hanging there, putting his hand into the pockets. There was nothing to help to elucidate the mystery. He went into his own sitting-room, and seated himself at the writing-table. He did not take up his pen to answer the letters that had come by the morning post. He sat thinking till the servant told him the horse was ready.

He threw himself into the saddle and rode to the Zemindar’s house, where he asked for Minachee. He was told that she was not there. Where was she? Gone to the temple, was the reply. What was going on there? he asked. They did not know. There was a tamasha last night in the tope; perhaps there was pooja to-day in the temple. He set his horse’s head in that direction accordingly; it was not far from the Zemindar’s house.

The temple was built within an enclosure surrounded by four walls. It consisted of a central block of a few courts and dark chambers; a goparum. or tower, and a cluster of rooms against the outer wall, which were used as dwellings for the attachés of the temple.

The sun blazed down on the baked landscape, and the air quivered with tropical heat. The fan-shaped leaves of the palmyras rattled with a harsh, dry sound in the hot wind.

Felix rode through the gateway into the enclosure, his horse sniffing the air and snorting suspiciously. There was not a soul in sight; and the place looked as dull and stupid as the idol enshrined within the windowless walls. He pulled up his horse and called aloud. A figure peeped at him from some hidden corner behind the building, and as quickly vanished. He shouted again, and from the other side came a boy, leading an old man, who advanced towards Felix with unsteady steps, and saluted him.

“I want to see Minachee, the dasi; I am told that she is here.”

The old man looked up at him like an owl in the sunlight, with the vacant expression a native puts on when he cannot or will not understand.

“Do you hear? I want to see Minachee. Go and call her. Tell her the Doctor waits,” repeated Felix, leaning towards him and shouting.

He was convinced by the look of cunning in the man’s eye that he heard and understood perfectly.

“She is not here,” the old night-bird replied.

“Then call Deva, her mother.”

His request met with the same vacant stare.

“I tell you I must see Deva or Minachee,” shouted Felix.

Becoming impatient of the poojari’s stupidity, he turned to the lad, and said in his natural voice,—

“Run and tell Deva to come.”

The commanding tone of the Doctor’s words made the boy prepare instinctively to do his bidding; and by that gesture he knew that the woman was there. But the man checked the boy, and tightened his grasp on his arm.

“She is not here; I assure the sahib that she is still in the Zemindar’s house. It is her home, and she never comes here——”

As he poured forth his tissue of falsehoods, Deva came out from the temple itself.

She was dressed in rich silk of a brick-red colour, edged with a broad border of gold woven into the cloth. The colours of the silk and the gold harmonised with the warm brown tones of her skin. Jasmin flowers adorned her hair, and her face was powdered with sandalwood and saffron. Native women age early; but Deva, to the European eye, would have been considered still in the summer of her beauty. Her own people, however, thought nothing of her charms—she held them by other arts for she lacked the rotundity of figure and plumpness of limb so essential to women of her age, who pretend to any matured beauty. But, on the other hand, she was neither thin nor gaunt; she was only spare. It was the spareness bred of activity of mind and body. The brain was always at work, plotting and scheming, making marriages amongst the townspeople, and as unscrupulously marring them.

She stood on the steps of the temple, where the full light of the sun fell upon her. The colour of her dress glowed under the blazing rays like molten metal, and the heavy gold ornaments glittered as though freshly turned out of the smelting pot. She might have been the spirit incarnate of the precious metal, newly risen from the secret crucible of mother Earth.

Felix waited for her to approach. She signed to the old man to go; then, descending the flight of the steps that led up to the entrance of the temple, she approached him with queen-like grace. He touched his horse and came up to her. The critical glance of the medical man detected unusual excitement in the sparkling eye.

“She has been drinking arrack or eating bhang,” was his mental comment.

“Where is Minachee? I want to see her,” he said.

“She is gone to Palamcotta.”

“You do not speak the truth,” he replied quietly. “She waits and listens there, at this moment,” and he pointed to the temple.

“No; not so,” said Deva, without turning her head. “She went away last night. The poojari sent her to Palamcotta on a mission.”

The Doctor regarded her with incredulity.

“I am sure she slept in the Zemindar’s house last night,” he said.

“Nay, she slept in no house. She started at two o’clock in the morning. It is cooler for the bullocks to travel in the night. She will have slept as she journeyed.”

“Did she go alone?”

Their eyes met, and the woman smiled.

“She started alone.”

The Doctor knew not what to believe. Was she lying? Or was she telling the truth in such a way as to leave him purposely under the impression that she was lying? He could not say, for he was not dealing with an ordinary native, but one who was highly educated in an Oriental sense of the word, and whose cunning it was not easy to fathom. After a pause she said,—

“Your brother was talking with her yesterday morning in the tope. If you want to know more about my daughter, ask him; he knows very well where she is.”

Again she smiled, and her eyes glittered with an unholy light. Checking the angry words that rose to his lips, he turned his horse and rode away. Deva watched him disappear through the gateway, the evil smile lingering on her lips. Then she glided up the temple steps, and disappeared within the dark mulasthanum, where the lamp burnt dimly in the murky air before the idol.

Deva belonged to the class of women known as dasies, who are attached to Hindu temples. They are the wives of the gods, and their profession is dancing amongst other things. At an early age they are married to the idol in the temple; or to some demon supposed to haunt a particular tree. Deva was the wife of the devil in the big banyan tree in the tope. Years ago she had been wedded to it with a ceremony and ritual, that, at the time, filled her with awe, and made a lasting impression on her young mind. She still remembered with a shudder how her bridegroom, the devil, howled his approval during the pooja, and mingled his hoarse voice with the tomtoms and the horns. The heavy chains hanging from the branches clashed, and the foliage rustled, as he shook the whole tree, stem and branch, in his pleasure.

After her marriage—she was only seven years at the time—her education was continued in the temple. She learnt to read with the other dasies, and studied Sanskrit, in which language the dancing-girls usually sing. She was taught to dance and pose and sing. She was initiated into the secrets of the Oriental toilette, and shown how to touch the lip and eyebrow with skilful hand; how to keep the skin soft and fine; how to heighten its tones with golden tints by the use of saffron and sandalwood.

At the age of twelve Deva went into the zenana of a Hindu rajah. The temple coffers were enriched by a large contribution of money; and the idol was afterwards presented with rice, butter and honey, periodically. Deva became the plaything of the zenana. The rajah loaded her with jewels and refused her nothing. Even the ranee was languidly amused at her pretty dancing and plaintive songs. For six years she remained there; and all the while the rajah was spoken well of, throughout his estates, for his munificent gifts to the temple. Then he fell sick; and one day a guru came from the north. He talked of a large temple far away, whose tank drew its waters from one of the springs of the Ganges. A sick man might assuredly find health in those waters. He hinted that the dasies of the temple were young and beautiful and very fair. As he talked he glanced disparagingly at Deva. In one short fortnight Deva’s happy life came to an end. The rajah departed on a long pilgrimage—such a good and religious man was he—and the dancing-girl, with her little daughter was sent back to the temple.

Life became monotonous and dull in the temple after the zenana, except when feast-days came. The daily ritual of helping to wash and dress the senseless idol, dancing before it night and morning, and singing hymns of love, was tame work after the other. The temple men and women looked on approvingly, for Deva danced beautifully; but a poojari is a poor man compared with a rajah. He cannot pet the graceful, accomplished dasi when she pleases him, nor feed her with sweetmeats and betel nut, even if he be so minded, the life almost unendurable, monotony and dulness ended. Her religious enthusiasm awoke, transforming her into a new creature. She entered into all the arrangements, made suggestions, and fired poojari and people alike with fanaticism. She put forth all her powers of attraction to lure the rich zemindars and chetties, who were not at all averse to treading in the footsteps of a rajah. She became the life and soul of each festival. The temple authorities were pleased that it should be so, for it brought them wealth.

Deva educated her daughter carefully, and married her to the idol in the temple. When she was thirteen she installed her in the house of the Zemindar of Chengalem.

Once more Deva was happy, although she was no longer queen. Her power in the Zemindar’s zenana was far greater than it had ever been in the house of the rajah. She ruled all those uneducated women as though they were children, and pulled the strings as she pleased. There was but one thing she dreaded, and that was the inevitable fate which overtakes every dasi so situated, the word of dismissal from the master. It came in her own case, and she saw it approaching in her daughter’s. In vain she decked the girl afresh and taught her new dances and songs. The evil hour must come, though the warning to depart had not yet been given. No help was to be had from the poojaries of the temple. It mattered little to them which of their dasies the Zemindar supported. It was just as good and religious an act to support one as another, especially as his offerings to the idol continued the same.

Deva in her despair bethought her of her husband, the mysterious spirit of the banyan tree. Perhaps the swami might help her. She had never neglected his worship, but had instigated his pooja at regular seasons without fail. She would try to invoke his aid, and he might destroy the new rival with terrible sickness, or might change the heart of the Zemindar. She considered how it might be brought about. There must be a feast, a big feast, in honour of the tree-devil, and the whole country side must be present with offerings. To this end she went to the wells in the mornings, and stood amongst the women, talking of the want of rain. The cotton crops were withering instead of ripening; the palmyras gave no toddy; the cattle were growing thin and weak; and here and there a house had been burnt. She hinted that the devil was angry; she, as his wife, should know it, and she said it, she declared it.

The dread rumour went abroad and spread throughout the town. The demon in the tope was wroth, and would work more mischief if he were not appeased. It was necessary that something more than usual should be done. His festival was approaching. There ought to be a great sacrifice of blood. Instead of the customary half-dozen of black goats, there must be at least fifty, and perhaps a buffalo.

Then there was a woman in the town who was ailing. Deva went to see her, and recognised her complaint at once. She was possessed of a devil. It was told to the sufferer, and she was watched. Before long there were unmistakable signs of possession. The woman herself said that she was afflicted, and she begged and prayed her people to take a stick and beat the devil within her. So they belaboured the poor creature’s shoulders, driving her through the town to the banyan tree, where she fell exhausted before the shapeless black stone. But it was all to no purpose. After a few days the devil returned, and she was worse than before; for now she called herself by his name. Moreover, stones were thrown on to the roof of her house, and strange lights were seen hovering round it at night.

Then a man fell ill with just the same symptoms, and became possessed. His relatives branded him with hot iron, heaping upon him the vilest abuse as they did so, in the hope that the evil spirit would leave him. The demon shrieked aloud and fled as the hot iron touched the flesh. But, alas! it departed only for a time. Deva went to see the afflicted man, and put a healing ointment on his wounds. She shook her head as she did so, and said that the devil would return as soon as they were healed; which it did. The very first day the man walked in the town with the eyes of all upon him, he fell down in the street, foaming at the mouth, and crying aloud that he was possessed. It was the busiest time of the day, when the market was full. He bit the earth, and dug his fingers into the ground, and it was with the greatest difficulty that they bound him and carried him home.

Deva came to see him again, bringing the old poojari of the temple with her. They talked long and earnestly by the man’s side as they watched him. The poojari declared it to be a very bad case, indicating great wrath on the part of the spirit. Preparations must be made at once for the feast, and the two possessed ones must be present at it when the time came. If they danced before the stone under the tree, the devil would go out of them, and they would be no more tormented.

“There must be a big tamasha with plenty of blood, plenty of toddy, and plenty of people,” concluded the old man.

The whole town was roused by the poojari’s words, and the people prepared to do his bidding. Who could tell what the malignant spirit might not do next, if he were not speedily propitiated?

Chapter III

A Devil-Dance

Oh, thou that delightest

In flesh and blood,

Be propitious!

Be propitious!

Quickly accomplish

Our desires.

Enter here.

Enter, enter!

Tread, tread!

Dance, dance!

— Gurura Pooran

A devil-dance of South India is a terrible affair. The unbeliever may smile, but there is no other word for it; it is a terrible affair. The matter seethes for weeks and months in the minds of the people; and an under-current of excitement, the outcome of superstitious awe, grows and increases, till it reaches fever height. It culminates in a mad orgy, wherein religious fanaticism in its worst form is mingled with eating and drinking to excess.

The ryots and toddy drawers of Chengalem had been wrought up to fever point; and a night was fixed for the dance, when the moon was new. For several previous evenings tomtoms were beaten, horns were blown, and processions were made through the streets. One or two women saw the demon in the form of a large solitary wolf, with flaming eyes and lolling tongue. This was a good omen and boded well. It indicated that the swami was pleased with the coming tamasha.

On the chosen night the women prepared no evening meal at their houses. It was to be eaten in the grove; and it was to be made of that portion of the sacrifices which was given by the poojaries to the people. After the animal had been killed, its head was presented to the swami, and its body was divided between the donor and the poojari.

No particular time was set for the assembling of the multitude. At sunset the women began to put their cooking pots together, piling them in loads on their heads. Baskets of rice, jars of honey, bunches of plantains, pots of toddy, were also poised aloft; and straggling down the road in an unceasing stream, the people wended their way to the grove. The men blew horns and beat tomtoms as they went; and the musicians piped on their strange instruments, producing thin squealing bagpipe tones without tunes. Long-legged boys, wearing nothing but the loin-cloth, drove black goats before them; the dogs and children mingled promiscuously with the ever-moving stream of humanity.

The tope was a scene of wild confusion. Fires, made of dried leaves and sticks, filled the heavy air with smoke, and cast a flickering uncertain light on the figures that moved to and fro.

The sun set in his usual garment of reds and purples, and night came on quickly. Still the people poured in, each party making its own little camp. The women fetched water from the well or tank close by, and boiled rice. Others carried their offerings to the big tree, where a poojari stood ready to take charge of them.

The lads drove up the goats, herding them together in a space set apart for the sacrificial beasts at the back of the tope. The frightened animals added their bleating to the din, and occasionally a buffalo-cow bellowed out her disquietude. The men blew horns and drummed with their fingers on the tomtoms just as their fancy seized them. The shrill voices of the children and howling of the pariah dogs completed the hubbub of the night.

A large circular space was kept clear before the banyan. There was no need to tell the people not to press forward—they were too fearful of the spirit to venture beneath the branches; nor would they willingly have gone behind the tree on the opposite side of the stone, where the trunk was hollow. The devil was supposed to pass in and out that way. It was also the path along which the beasts would by-and-by be driven up for sacrifice.

Deva was present; she wore a fine white muslin cloth, and she had gold ornaments in her hair. A thick garland of oleander and jasmin flowers adorned her neck. She no longer moved amongst the people, but stood under the tree itself, its priestess and presiding genius for the night. Several poojaries were there, although only one would perform the ceremonies, and a little knot of dasies, chiefly as spectators. They moved about amongst the people, but Minachee was not with them.

An hour or so afterwards the business of the evening began in real earnest. By this time all the company had come, and being hungry, they were clamouring for the pooja to commence. Large cressets of oil with a floating cotton wick were lighted; also a fire was made to the left of the stone. A pot of butter was placed on the burning sticks by a poojari, who stirred the grease as it melted. The spectators stood in a wide circle, and gradually ceased their chatter as the ritual proceeded.

An elderly man came forward, naked to the waist. He had marked himself on forehead and breast in sacred ashes with the swami marks of the caste. He took the smoking oily butter from the pot with a brass ladle, and poured it upon the devil-stone. The crowd, silent and observant, cast fearful glances at the tree. At any moment now an awful manifestation of the devil might be made.

A young man came from behind, leading a goat into the clear space, midway between the assembly and the tree. It was his offering, which he presented on behalf of himself and his family.

Deva stepped forward, bearing in her hands a sword, which she gave to the poojari. She was followed by an attendant, carrying a brass basin of water. She dipped her hands in it and sprinkled the head of the goat. The poojari, holding the sword aloft, ready to strike, watched the animal intently; it did not stir. A second time Deva cast the water upon it from her cupped palms, and the goat shook its head. The sword flashed in the yellow light of the cressets; the head was severed in one blow, and the bleeding body fell to the ground, where it lay in a crimson pool.

The dasi picked up the head, and held it over the devil-stone, so that the blood dripped down upon it. As she did so the assembly called aloud to their gods, the tomtoms beat and the horns blared. Rice, camphor, fruit and sugar were brought, and set out on green leaves with the head of the goat before the stone. The people made a low obeisance, and the owner of the goat carried away the carcase to be divided between himself and the poojaries. Another goat was brought, and the same ritual was performed. Deva sprinkling the water, and afterwards lifting the bleeding head above the stone, so that the life-blood might drip upon it. Again fruit, rice, sugar, camphor were brought, and as they were offered with the ghastly trophy the people shouted again.

Some three dozen animals were killed in this way, and a row of heads, alternating with the leaf-platters, garnished the platform. Then Deva held up her arms. It was enough for the present. The feast must be prepared and eaten before further pooja was done.

She took the sword from the poojari and stuck it point downwards in the ground, immediately in front of the altar. The cressets were extinguished, and the semi-circle broke up into groups. Before long a savoury smell of curry went up on the night air. When the meal was ready, the men seated themselves by their camp fires, and were served by the women. Afterwards the women and children sat down to supper, and the men took deep draughts of fiery toddy, talking and laughing louder than ever. There was certainly plenty of toddy, as the poojari had said there should be, and the women drank too.

The camp fires died out, and the grove became dark as night. The time was approaching for the event of the evening to take place—the devil-dance, in which the two possessed ones were to join. The cressets were re-lighted, and the spectators formed themselves again into a large semicircle. Behind them was the thick blackness of the moonless night, enhancing the brilliancy of the oil lamps. Before them was the blood-smeared stone, with its row of ghastly trophies.

Once more Deva came forward, this time bearing a =garland of pink oleander blossoms instead of a sword. She threw the wreath over the stone, while the tomtoms beat in low measured time, and the pipes sent forth a thin wailing. She raised her hands towards the tree as though in supplication, and asked her strange husband to grant her a boon. Superstitious to her very heart’s core, she watched the big banyan, half hoping, half fearing, a manifestation; but none came.

Keeping her rapt gaze fixed, she began to sing. Her feet moved to the beat of the tomtoms, and her body swayed with cultivated grace. The movement was quiet, and the singing was low; but in a short time passion crept into song and dance, a subtle pervading passion, which thrilled through the breasts of the onlookers, and stirred their inmost souls. The words of the song were of love, the bride’s invitation to her husband and her god to come, and come quickly, to her bower.

As Deva sang, the crowd parted, and the possessed man and woman were pushed into the light. They fell prostrate before the stone, apparently in a swoon. Presently they stirred, shaken with a strong convulsive shudder. The movement did not escape the eyes of the people. They shouted the name of the demon, and as the word fell on the ears of the two, they rose to their feet, staring wildly about them.

Deva sang on, circling round the possessed as she danced. More convulsive movements followed with a swaying of the body; their feet trod in a measure to the tomtoms, and the dance began in good earnest.

Never was there wilder or weirder scene. The two possessed ones stepped round and round, swaying and rolling themselves from side to side with arms flung above. Their long black hair, the man’s as long as the woman’s, became unfastened, and swung with their bodies in a tangled mane. Their fingers closed and unclosed, grasping the air or seizing the clothes that enveloped their bodies.

Then a fit of fury took them, and they tore their hair in handfuls. All the while Deva, with trained movement instinctive with grace, floated round them, ever singing and posing, a wonderful contrast to them in their untutored contortions.

Now the height of madness came upon them. They foamed at the mouth and shrieked, and laying their hands upon their clothes, they rent them in their frenzy, till their garments fell from their bodies, leaving them naked. And thus they danced, and swayed, and writhed, whilst the tomtoms beat wildly, the horns blared, and the people shouted. Madness seemed to have come upon the audience as well as upon the performers.

Suddenly it all came to an end. A marvellous thing happened, striking awe to the hearts of all. There was a sound in the branches’ above the stone, and a large dry stick fell at Deva’s feet.

A cry was raised that the demon showed himself; a dark form glided from the tree and disappeared into the black shadow of the grove.

In a moment the lights were extinguished, the noise ceased, and a fearful silence reigned. Not a sound was heard but the bleating of the goats which remained over from the sacrifice, and the distant howl of the jackal.

For a space of fully five minutes the people lay motionless where each had dropped to the ground, not daring to move or breathe, lest the devil should take them.

Then the voice of the poojari was raised, commanding that the cressets should be lighted again. In fear and trembling the excited crowd rose to their feet; women’s tongues were loosened as suddenly as they had been silenced, and a perfect babel commenced. The men drank more toddy, and called aloud for Deva to continue the dance. But Deva was no longer there; she had disappeared. Nor was the old poojari, her coadjutor, anywhere to be seen.

The women glanced with awe at the tree and its gory flower-bedecked stone. Could the swami, in the shape of a grey wolf, have carried away his wife? And had the poojari gone after him to make him give back the temple property? for Deva belonged to the temple quite as much as to the tree.

Whilst they talked and speculated, the object of their discussion came swiftly out of the darkness behind the tree into the light. If she had been excited before, she was now transformed with passion. Her eyes shone with the wild light of fanaticism, and her breast was filled with a new zeal.

Without waiting for the poojari to speak, she commanded silence. She told the people that she had talked with the spirit, and the spirit had said that they had not shed enough blood. More goats must be killed. She had hoped that the swami would have been satisfied with the blood that had already flowed, but he cried for more, more, more.

A murmur of applause ran through, the crowd; and, as if in obedience to her request, some of the men moved towards the herd of goats. But she stayed them with an imperious gesture.

“Stay where you are, and let not a single person stir, for the swami still walks. He bids you drink and be of good heart, while I, his wife and slave, bring the offering.”

The men were more than content, for not one of them relished the notion of meeting that terrible demon; and Deva left the circle, followed only by the poojari carrying the sword.

There was renewed bleating amongst the goats and a frightened bellow from the buffalo. Then all was still, and Deva returned, bearing a large circular basket full of bleeding heads. The basket was put on the platform before the stone with the rest of the trophies already there.

The dance recommenced with the same low tomtoming and music, Deva leading it with her singing and dancing. The song was more impassioned than before, and hard indeed must have been the heart of man or devil that could resist such a passionate appeal from so beautiful a woman.

The possessed ones, clothed again, were pushed into the circle by their friends to join in the dance. Deva paid little heed to them this time. Her propitiatory ceremony was made entirely on her own account and on behalf of her daughter. Her whole soul was given over to the task of softening the swami’s heart towards her, and in enlisting his help in her hour of need.

Fast and furious went the dance. Now and again a man or a woman came out of the crowd to join in that mad orgy. The process was always the same: a swaying of the body and a swinging of the arms; a tossing of the head, with its loosened, streaming hair; a treading of the feet; and finally a frenzied tearing of the hair and clothes, till the dancer fell naked and exhausted in the dust.

Such, with varied ritual, is the devil-dance of South India. The dasies of the temple are not present as a rule; and the dancers sometimes vary the ceremony by wearing hideous masks—fancy portraits of the demon.

On the night in question, this terrible devil-dance continued till about two in the morning, when the cressets burnt out. With darkness came peace. The people, heavy with drink and worn out with excitement, lay down promiscuously, and sank into deep, dreamless slumber. The dasies and poojaries found a quiet corner, and wrapping themselves in their clothes, they were also soon asleep. Only two people remained awake; they were Deva and the old poojari.

When silence reigned around, broken only by the regular breathing and snores of the sleepers, the woman and the man crept away to the place where the sacrificial animals had been penned. There, by the dim light of an oil lamp, they stooped over the headless bodies, pricking them with pins, branding them with hot irons, and cutting them with knives. Long did they sit there, absorbed in their horrid ceremonies. When all was done, they threw a grass mat over the big black carcase of the buffalo. It would be buried in the morning, but the goat’s flesh would be used in the temple. No one would dare to touch the meat, as it was guarded by the demon, therefore the poojari had no fear of pilfering fingers.

Together Deva and her companion walked back to the temple. Once only did she speak; it was just as they parted in the compound.

“That was well done to-night, my father,” she said.

To which he replied, “Truly, my daughter, it has never been so well done since the English Government had rule.”

* * *

Dr. Manning was puzzled by Deva’s manner when he saw her the day after the dance, and he was not satisfied with her appearance. He felt convinced that she was labouring under some strong excitement, and he did not think that it was anger. It was more likely to be triumph; the triumph of success in one of her many plottings.

Had it anything to do with his brother? The Doctor was well aware of the position Minachee occupied in the Zemindar’s household; it was one much coveted by the temple dasies, and he could not believe that the mother would allow the daughter to give it up; nor indeed do anything by which that position might be endangered. He therefore doubted the insinuation made by the woman, and was inclined to think that Deva was rejoicing over some piece of mischief, in which his brother had no part.

On his way back he called at Mr. Holdsworth’s bungalow to see Beryl. She was mending fast, and did not need the medical man any longer. She had slept all the morning, and had awakened much refreshed. A good lunch, together with the repose, had thoroughly restored her nervous system, and all signs of hysteria were gone.

Felix found her with her mother in the drawing-room.

As he entered, Beryl’s eyes sought his, and there was the slightest raising of the eyebrows on her part. Whatever the query might be it was understood, and a reply was given in a scarcely perceptible shake of the head.

It was early in the afternoon for tea, but Mrs. Holdsworth suggested that it might be acceptable. Felix was hot and thirsty after his ride, and not at all averse to the suggestion. The talk while they waited was commonplace, and chiefly between Mrs. Holdsworth and Felix. Beryl, leaning back in her chair, listened, her eyes seeking the Doctor’s face with a wistful glance now and then. She made no attempt to get rid of her mother, however, nor to exchange any words with her visitor.

When the tea came in he handed her a cup, and was unobtrusively attentive to her smallest wants. She always liked him better without his brother; and to-day, in his double capacity of friend and medical adviser, he seemed doubly pleasant. She was quite thankful that Will was not there; she could not have borne his light chatter. Besides, something had passed between herself and Will, which made her hope that he would keep away for a few days, even whilst it caused her to feel the more anxious to hear news of him. If Mrs. Holdsworth had given her the opportunity, she would probably have said something to Felix, yet she was not sure that she had any right to betray the confidence of one brother to another.

Therefore she did not seek the opportunity, but let matters take their course. Meanwhile, there was no doubt but that she derived actual pleasure from watching the kind but determined face, so full of the strength and force of character which the younger brother lacked.

Whilst they were drinking their tea, Major Brett arrived. After greeting the company, he turned to the Doctor and said, “I have just been to your house, Manning, to see your brother, but he was not there. He promised me faithfully that he would come to my bungalow this morning to talk over that horse of his. It is a capital beast, and I am quite ready to pay him his price. Why did he not come?”

“He went out last evening and has not returned,” replied Felix.