Colonel of Dragoons

For

My Father

H. A. M.

Foreword

This is an account of the Earl of Peterborough’s expedition to Spain in the period from September 1705 to September 1706. There is good evidence for believing that all the events described did actually take place; the persons mentioned actually lived, and did what they are said to have done, with the exception of Colonel Awbyn and the officers junior to him in the Queen’s Dragoons, a fictitious regiment which takes the part actually played in the campaign by the Royal Dragoons.

The reader has a right to some explanation of this substitution of a fictitious for a real regiment. The campaign is I think unique in English history; at least, I can think of no other in which an English commander-in-chief has turned himself into a guerrilla leader, has driven before him, by bluff and nothing else, forces usually three times, and sometimes twenty times, his own strength, and finally has thrown away the fruits of victory by the defects of his own character. It is tragedy rather than history and there is about it a dramatic symmetry, a rhythm of ebb and flow, that is too good for real life.

If I had been an Elizabethan, I should probably have made a play of it, but it would overflow the modern stage. The novel of course is the form in which most of us nowadays try to put what we have to say and it is a carpet-bag into which a good deal of incongruous luggage has at one time and another been crammed. But I do not think this will quite make a novel; I want to stick exactly to what happened. And I do not personally feel at ease with the form known as fictional biography. It is partly that I find my belief suspended by constant suspicion of the writer; how, one continually wonders, does she know that! Rather deeper is the feeling, perhaps over-scrupulous, that there is some disrespect for human personality involved. It is perfectly proper for a novelist to exercise seignorial powers over his characters, but I am doubtful whether they can be extended over people who really lived. Everyone has a right to some reserves, even in death, and to me it seems fair to judge a man by what he has written or said or done, and to make inferences as to what he thought, but unfair to enter his mind, to draw aside the veil, and to say positively that he did think or feel this.

Neither a play, nor a novel, nor ‘fictional biography’, then, but a chronicle of what happened as it might have appeared to a group of people living at the time; that is my choice. In fact, it is what for some inscrutable reason is called a documentary, and in the manner of the documentary the historical persons are displayed mainly through the impression they make on fictional characters. I have occasionally put words into historical mouths when there is an historical reason for believing that something of the kind was said; more often I have reported in slightly more modern idiom the substance of what the character said in letters or diaries; there is usually a fictional character to hear what is said. The fictional characters thus become the vehicles for a periscope from which the historical are surveyed. The only exception to this is the chapter in which Godolphin is reading his letters; here the reader is allowed to read the original words of the letter over the Lord Treasurer’s shoulder and can judge for himself.

In Colonel James de St. Pierre, who commanded the Royal Dragoons for part of this period and whose diary and letters are among the sources of our knowledge, I had just the straightforward regimental soldier I wanted as a contrast for the erratic brilliance of Peterborough, but I did not know enough about him to use him honestly as the periscope. Apart from the fact that relations of his were living not long ago, I respect him too much to invent what I do not know. And, to be honest, I craved for some remnant of the novelist’s feudal powers. So in his place I have put Colonel Awbyn and the rest; I know all about Colonel Awbyn because he is my own.

This explains why I have substituted the Queen’s Dragoons for the Royals; we know the names of every officer in the Royals at the time and of several one can form some impression. But I want more than that, so I have invented a set of men whom I can picture just as I like. Their concern, however, with brevets, staff-officers, precedence, new hats and the like is all there in Colonel de St. Pierre’s diary and letters. The name of the Queen’s Dragoons is not a bad one for the Royals, who were raised in 1661 for service in Tangier, part of the dowry of Charles II’s Queen; the foot regiment raised at the same time and for the same purpose has always been called the Queen’s. And in fact the Royals were occasionally referred to as the Queen’s in this period.

There are longer notes at the end about the manuscript sources, which explain why I have chosen one version of what happened rather than another; there has been a good deal of controversy about everything to do with Peterborough, which it seemed as well to keep out of the text. There is also a note on his life before and after this critical year and notes giving the modern names of regiments and other points that will not interest everyone.

I am very grateful for the help I have had from Professor Starkie of the British Council’s Institution in Madrid and from Mr. C. T. Atkinson of Exeter College.

P. W.

Part One — Barcelona 1705

Chapter 1

Midnight

September 12th, 1705

On September 12th, 1705, a little before midnight, Colonel James Awbyn was walking back from the general’s quarters in San Martino towards the camp. He walked slowly, being in the mood when thought flows with the movement of the limbs; he was thinking things out and did not want to reach his tent before he had finished. A servant walked in front of him, carrying a lantern; the moon was in her last quarter and would not rise for some hours. Colonel Awbyn called to him to go slowly and paced on, thinking how he should deal with the distasteful task he had to face tomorrow.

He had been a soldier for twenty years and for most of that time at war; he could never wholly cease to be alert when the enemy were near, and at present the unconscious part of his mind was standing sentry, ready to give the alarm at a moment’s notice. As a matter of fact, the enemy were very close; if they had wished, the garrison at Barcelona could probably have made things uncomfortable by indirect fire from their batteries; they could certainly have made some very troublesome sorties. But they did nothing; it was, to Colonel Awbyn’s mind, not the least odd part of the whole affair that they had so far stirred so little. They had done nothing to oppose the landing of the troops, nothing to molest them in the three weeks since the landing. The camp might have been on Hounslow Heath; you could walk through the night thinking of how to attack the town with no more than a faint feeling that the peacefulness was unnatural and therefore dangerous.

What he disliked about tomorrow’s task was not the substance of his orders, if they could be called orders; no, there he was in agreement with my lord and at odds with the subordinate generals who made up his lordship’s council of war. It was the way of going about things that he did not like; it was, he felt, unsoldierly; it was un-English. And he, who had talked French to his mother, whose name till his father’s death had been St. Aubin, well, he had come to like the English way of doing things.

A sentry challenged sharply; they were in the camp; another challenge; they were in the lines of his own regiment, the Queen’s Dragoons. They were approaching from the rear, moving towards the enemy; the camp was drawn up to face Barcelona, and they had first to pass the low ridged horsemen’s tents and the lines where the horses should have been picketed. But half the lines were empty and although from the rest there came the occasional stamp and snort, the sharp smell of stable litter, all the familiar and usually pleasant evidence that horses were there, it did not bring satisfaction to the colonel tonight. The regiment had brought from Lisbon only enough horses to mount four troops out of eight and they were most of them wretched screws, provided under treaty by the King of Portugal for nothing, and in Colonel Awbyn’s opinion worth about that. It was a slight but definite discomfort to be reminded of their existence.

The colonel and his guide passed the lines of men and horses and now they were among the subalterns’ tents, which loomed about them as dark shapes, round and flat topped, like overgrown haycocks. His own tent stood alone, ahead of his troop commanders and field officers, but in rear of the regimental staff and the sutlers. He had given orders that a light should be left burning; now he could see the lantern, a golden blur shining through the ticking. It was not in the doorway as he had expected but inside. He was irritated at the interruption to his thoughts, and for a moment considered turning away and continuing his walk. But the ground was uneven and divided; without a light he would stumble, and it would be eccentric to keep back a man with a lantern merely for a midnight stroll. He dismissed the servant, who had been sent with him by an aide-de-camp of the general’s, and turned to his tent. In the doorway, he stopped abruptly.

There was someone lying on the bed. Colonel Awbyn had expected to find someone, for he had ordered a dragoon to wait for him. But the man was on duty; that he should be asleep on his colonel’s bed was a neglect and an impertinence that could not be tolerated. Colonel Awbyn, however, controlled his first impulse of rage and uttered the man’s name in a voice sharp and cold with anger.

‘Hansford!’ he said.

The figure on the bed sat up and rubbed its eyes.

‘It isn’t Hansford; I sent him away,’ it said.

The speaker stood up. There was not much room in the small, round tent, and his movement brought him close to Colonel Awbyn.

‘Peter!’ began the colonel in a voice in which there was nothing but surprise. But he went on more coldly:

‘May I ask why you sent him away? He had my orders to stay.’

‘I know. But I wanted to talk to you and thought I would wait. Hansford would have been a nuisance.’

‘I kept him here because I was on duty and I might have needed to send a message when I got back,’ said the colonel coldly. ‘It was not a mere whim. I shall be obliged if you will respect my orders in future.’

‘I’m sorry, Sir. I was wrong; it shall not occur again.’

‘We will say no more about it,’ said the colonel. His manner changed and he resumed their normal relationship. They were brothers-in-law and both Huguenots; but even when alone they spoke English. Colonel Awbyn had made this a rule when Peter de Nérac joined the Queen’s Dragoons and its wisdom was so apparent that they never relaxed it. He went on:

‘But I am glad to see you. Peter, I will make a wager with you. I will lay you—’ he paused for a moment and went on impressively, for it was a large sum for a man with little besides his commission—‘I will lay you fifty guineas that within a year from today Charles III is proclaimed King of Spain in Madrid.’

‘Evens?’ Peter asked.

‘At the best. The Duke of Anjou is on the throne. He has been crowned in Madrid. He has Spain and France behind him. We have nothing in Spain but Gibraltar and the ground we stand on. You ought to give me odds. Everything is against us but one thing.’

‘And the one thing I suppose is my lord Peterborough. I should have guessed where you had been even if I had not known.’ The lantern threw the contours of Peter’s amused face into sharp relief. It was a face still round with youth, though scarred by a sword-cut on the cheek; its expression at the moment was characteristic, displaying perfectly the Gascon combination of sardonic scepticism in council and reckless daring in action.

Colonel Awbyn’s brow darkened again.

‘You knew where I had been? How did you know?’

‘Hansford told me, of course.’

‘And he, I suppose, had it from my lord’s messenger. There is too much talk in this camp. Not a sentinel but knows everything we do. Didn’t you—before you were aide-de-camp to the King I mean—know everything that was decided in every council of war?’

‘I knew what every man in the camp knew, within twenty-four hours.’

‘And then it is just so long again before the French know. Well, at any rate, that is another point against us and another reason for not giving you better odds. Will you sit on the bed? What about the fifty guineas? Do you take me?’

Colonel Awbyn threw his plumed hat on the bed, unbuckled his sword, took off his coat and gorget. He moved round to hang his clothes on the pole and then sat down near the head of the bed. He wore his own hair, a thing less uncommon among the Huguenots than among English officers.

Peter looked at him seriously.

‘It is not a fair bet,’ he said. ‘I mean not fair to me. As you say, we have only this corner of Spain. If we make the kingdom ours, you win your bet and I pay. But if we do not, if we are beaten, it is not very likely that we shall both be alive. So I do not get my money if I win.’

Awbyn made a quick movement with his hand.

‘Death ends all bets,’ he said. ‘All the same, so much is against us the odds ought really to be longer. Do you take me?’

Peter thought again.

‘You lay fifty guineas on the strength of my lord’s character. Well, I,’ said Peter, ‘I will take you, on the strength of His Majesty’s. Though it is as much his Austrian advisers as himself. Isn’t there some riddle of the philosophers about an irresistible cannon-ball meeting an immovable post; You wager on the cannon-ball, I on the post.’

Colonel Awbyn took out a note-book from the half-open saddlebag by the head of his bed and made a note of the bet.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘we are in the hands of God.’

‘There is no reason, all the same, why one should not calculate the chances of a purely human success,’ said Peter with a look of amused affection. He went on:

‘But what have you been hearing? Or ought I not to know, for I am on the staff of the immovable, you must remember?’

‘You should be more careful what you say,’ said Colonel Awbyn. ‘You should make it a habit to speak with respect of the King.’

But he spoke automatically and did not wait for an answer, knowing well that Peter would pay little attention to advice from a brother-in-law and feeling reluctant to fall back on orders from a colonel. He went on to tell how the general had sent for him.

Dinner had been finished, and the men had yawned through the rest of the hot afternoon and evening. Tattoo had been beaten at last and, half an hour later, Colonel Awbyn went out to follow the officer of the watch on his rounds. It was a precaution he had taken several times since the troops came ashore, because he was uneasy about the men’s state of mind. There was gloom and uncertainty in the camp; the difference of opinion between the Austrian court and the English commander-in-chief was well known; there were councils of war daily and nothing done; there was general despondency. And Colonel Awbyn knew well that despondency leads to slackness, which in the face of a resolute enemy would sooner or later mean surprise by night.

When he came back from his rounds, there was a messenger to summon him at once to the general’s lodging, a quarter of a mile away in San Martino. Having ordered Hansford to wait up for him with a light, he walked there without delay, arriving as Lord Peterborough was finishing business with his secretary Mr. Furly. He was asked to wait, and sat watching, fascinated by the speed with which his lordship’s quill drove over the paper, a quill that never paused to search for a word or hesitated as to the propriety of an expression, that was in no way interrupted by the stream of orders that poured from his lordship’s lips at the same time, so fast that it was all the secretary could do to make notes of them.

At last the business was finished, Mr. Furly was allowed to go, and the thin brisk man at the table came to meet Colonel Awbyn. He took him cordially by the arm and drew him into his bedroom, where he took off his coat and wig and sat down by the bed in his shirt, making the colonel sit too. It was at this point in his story that Awbyn found it difficult to convey the impression he wanted. He was searching for words, slowly and clumsily, when Peter interrupted.

‘But I know him,’ he said. ‘I know what you mean. I know that quick way he has, like—like one of those little birds that sit on a rock in a stream and bob up and down. And I know that way of taking you by the arm and making you feel that you’re the one man in the world whose opinion he values. He’s done it to me. I told you how he spoke to me in the King’s ante-room, the day I kissed hands—as though I were a major-general instead of still a long way from my captaincy.’

Colonel Awbyn agreed. Yes, that was how it was. You felt yours was the only advice that mattered. He went on with his story.

‘He said he had heard I was one who had always expressed myself in favour of undertaking the siege—’

Again Peter broke in.

‘I told him that,’ he said.

‘Richards, too, I think. But he wanted to know why I held such views. He knows what the men are saying, that we came here like fools and now we are going away like cowards. But, you see, Peter, he is neither fool nor coward himself. He thinks night and day what he ought to do. He must find a way of taking Barcelona or doing something else big enough to make a stir. Then we shall get help from the Spaniards, but not till then. He told me all this and then he said:

‘“Look at my difficulties. Here I am, by the Queen’s orders instructed to pay the greatest attention to the wishes of the King of Spain. Yet I am constantly urged by the Ministry in London to go to Italy to help the Duke of Savoy. Now the King of Spain will not hear of my going to Savoy; nothing will satisfy him but Barcelona. And the Portuguese say the same. Very good; I give in to them; we come to Barcelona. I am promised 1200 horse and 6000 foot, regular Spanish troops that will join us as soon as we land. But not one soldier comes to the flag.”

‘“But the country people are for us,” I said.

‘“What good is that?” says my lord. “Higglers and sutlers, peasants with baskets of oranges.”

‘“More than that,” I said. “There must have been fifteen hundred miquelets, and each of them has a musket and a pair of pistols.”

‘“And will run away at the first shot,” says my lord. “Irregular troops are no good but to pursue a beaten foe. If they would submit themselves to discipline and join a regiment of regular soldiers, they would be worth something.”

‘“They know we are not in earnest,” I told him. “They can see we are not setting about the siege of Barcelona. Till we do that, why should they risk their lives? They risk more than we do; we can go away, they have to stay. And they have wives and children. They will declare themselves once we are committed to the siege.”

‘“But how can we commit ourselves to the siege?” my lord asks. “I am tied by my orders. I must take the opinion of a council of war for everything I do. And every general is against a siege. The Dutch are against it. Scrattenbach is as definite as our own English generals.”’

Here Peter spoke again.

‘And they are right,’ he said. ‘And in your heart of hearts, you know it, James. You would need thirty thousand men to invest Barcelona, and we have not seven. The garrison is as strong as we are. It is against reason. And once we are committed to a siege, the French have only to bring up a few horse. Nothing is easier for them than that; Aragon is theirs; they hold all the country from here to Madrid. Then they can cut us off from all provisions except what we get from the fleet. And the fleet will not be here long; winter is coming, we have no port in Spain; they must be home before the autumn gales. We cannot hope to have the ships here a month from now. The Dutch talk of going already.’

‘I know, I know.’ Colonel Awbyn made an impatient gesture; he was a man to whom words usually came slowly and it was an irritation to him to be unable to express the deep feeling which he knew was right. He wanted to say that the moral in war is more important than the material; but he did not know how. What he did say was:

‘But this is not the Netherlands. This fortress was not built by M. Vauban or M. Cohorn. These are not French troops. Some of them are Neapolitan; they would as soon have an Austrian King as a French. Some are Catalan and they much prefer an Austrian. Even the Castilians are for King Philip only because the Catalans are for King Charles. The townspeople are for us. Once make a breach and you will see. It is not a matter of rules.’

Peter shrugged his shoulders.

‘If a general in the Netherlands attacked a fortress with a besieging army no stronger than the garrison, he would not only lose his commission, he would end his days in Bedlam.’

They had been through the argument before; there was no need for either of them to elaborate it. Awbyn continued:

‘Well, my lord thinks as you do. He thinks the generals are right as to a regular siege, such as the King begs him to try. I believe he would try it, though, to please the King, if he could. But how can he try it, when he has been ordered to listen to the advice of a council of war and they will not agree? It would cost him his head in England if he failed. He has worn himself thin with trying new plans, with running to the fleet for help.’

‘There have been plenty of new plans,’ Peter agreed gloomily. Both were silent, remembering how the first council of war had given a decided and unanimous opinion against the siege; how a second had considered the more limited project of a battery to breach the walls but no lines of circumvallation; how the engineers had objected to that; how the fleet had been asked for help to man the trenches but had offered too few men, and those governed by such careful rules as to make them seem fewer still. It had gone on and on, councils of war daily and nothing done. There they were, encamped almost within cannon-shot of the walls and nothing done. Nothing done day after day. Only the siege of Barcelona would please the King and the generals could not be brought to that. They would agree to anything else, but nothing would make them shift on the siege. One by one they had been taken aside privately by the King and his ministers; polite, embarrassed, obstinate, they had listened and gone away unconvinced. Councils of war at midnight; councils of war in the presence of the King, on board Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s flagship the Britannia, at the Earl of Peterborough’s quarters; at the Dutch general Scrattenbach’s quarters. But nothing done; nothing done; only plans changed as soon as made, only rumours in the camp. They were all to march to Tarragona; they were to start the siege tomorrow; they were to march to Madrid; they were to march to Valencia; they were to invest the town for eighteen days only and then if it had not surrendered sail to Italy. The King’s Prime Minister, the Prince of Lichtenstein, had thrown a stool at Mr. Furly’s head for bringing him the minutes of a council of war he did not like; the King’s military adviser, Prince George of Hesse, had not spoken to my lord Peterborough for a fortnight. Only one good piece of news, that in Flanders, the Duke of Marlborough had outwitted the French and forced the lines of Brabant.

Colonel Awbyn went back to his discussion with the general. He said:

‘He will get what he wants in the end; he never rests.’

‘Well, but what advice did you give him?’ Peter asked.

‘“You have landed,” I said, “you have made promises, you have put out declarations in the Queen’s name. How can you leave these poor Catalans to the mercy of a cruel and irritated enemy?” That was what I said to him. The English of course do not understand all that we do, Peter, of the mercy of the Grand Monarch. “How can you answer that to the Queen?” I asked him. What will Europe say of it? It would so tarnish the glory of the English that it is much better to venture losing the whole army than to leave these people.”

‘He took it in very good part. He had asked me to be frank. “But I am not going to leave them,” he says. “Since the generals will not agree to a siege, I am going to Tarragona.”

‘“To embark?” I asked him.

‘“No, to make a magazine. Collect stores, disembark powder and shot, before the fleet leaves us. Then with Tarragona at our backs, march to Madrid.”

‘“March to Madrid?” said I. “How can you? You have no pontoons to cross the rivers and no horses to pull your guns. There are no horses in Catalonia and if you had horses, you have no wagons. You cannot march to Madrid. It is far worse than the siege. All you have to do is to take the town.”’

‘He is right, all the same,’ said Peter. ‘Only it would have been far better to have marched from Valencia. We should have landed there and marched straight for Madrid, as my lord wanted, but the King would not let him. A shorter road and much easier. And there are horses and mules in Valencia. But one way or another, march to Madrid. Would the Duke of Marlborough waste his time here? He would march for Madrid, just as he went to the Danube last year.’

Colonel Awbyn disregarded this.

‘“But how am I to take the town?” my lord asks me. So I tell him that we are drawn up in the best place for a camp, with the strongest side of the city towards us. But the weak side of the town, the best for an attack, is inland to the south. There is a long stretch of curtain wall there, with no flanking fire but from a few small round towers. “Let your batteries play on that and you will make a breach in a week,” I said. There would be no need for trenches. The troops for the assault would lie in the convent, a long musket-shot from the walls. And when you make the assault, the town will rise, I told him.’

‘Your batteries would be under cross-fire from the fort of Montjuich,’ said Peter. He had listened attentively; this plan was new to him. ‘There would be fire from the city and cross-fire from the fort. Your guns would be dismounted the first day.’

‘There is a great deal of broken ground. You could site the battery so that it was hidden from the fort. It would be a slow business bringing up more guns and placing another battery for counter-fire against the fort. The elevation is too great except at long range.’

Peter agreed to the second proposition.

‘Montjuich is a steep hill and high,’ he said. ‘But I should like to see this site of yours. What did my lord say?’

‘He was much taken. He said he had noticed the weakness of that long stretch of curtain. And then, Peter, then, he put on me such a thing—’

‘What was that?’

‘He has told me to go tomorrow to Prince George of Hesse and tell him my plan—but it is not to come from my lord, it is to come from me! Now who am I to suggest a plan to a Field-Marshal of the Empire? Without invitation, too, mark you, for I have hardly spoken a dozen words to the Prince in my life.’

‘He is a fine officer,’ said Peter thoughtfully. ‘He is a soldier.’

‘That does not make it easier. I tell you, Peter, this is a politician’s way of going about things and I do not like it.’

‘You didn’t protest?’

‘I had no chance. In a moment, there was an aide-de-camp in the room, being ordered to bring in some deserters from the enemy to be questioned at dawn tomorrow. At dawn, mark you, and he will question them himself; there is not one of us but Brigadier Stanhope and Richards who speaks Spanish as he does. Next moment, he was back at his dispatches and his quill flying over the paper like an Arabian horse. I had no time to protest. And besides, Peter, to be frank with you, I was swept away. My lord is not a man you can protest to. He will get what he wants; he never rests.’

‘Well, I wish you luck. I shall win my bet, I am afraid, but I would rather stay alive and pay you. We must sleep. Good night, James.’

The colonel stepped to the tent door when Peter had gone and stood for a moment looking at the stars. He said his prayers standing thus. He was not, he would have said himself, a specially religious man; it was his father who had left France for the sake of his religion. His father had died while James was a child and his mother had continued to bring the boy up in his father’s faith. James had accepted it without very deep thought; indeed, it did not seem to him that there was much thinking needed. To fear the Lord and do his duty, that was his creed. He did not expect God to interfere in the dangerous world in which he lived and he supposed that, like many a good commander, God liked best those of whom he heard least. The only exception he made to this was Gabriel, his young wife, Peter’s sister; her he did commit to God’s care every night. But just as every man in an army can be conscious of the leadership of a good commander, he knew God was there all the time, and there were times when he was conscious of His presence. Beneath the stars in the stillness of the night, at sea on the tumultuous waves, near to death in battle, those were the times when he knew He was near. He knew it tonight and when he had finished the prayers in French which he had learnt from his mother he repeated in English the Hundred and Fourth Psalm:

‘Praise the Lord, O my soul; O Lord my God, thou art become exceeding glorious; thou art clothed with majesty and honour.

‘Thou deckest thyself with light as it were with a garment; and spreadest out the heavens like a curtain,

‘Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters and maketh the clouds his chariot and walketh upon the wings of the wind.

‘He maketh his angels spirits and his ministers a flaming fire.’

He had learned the words of many of the psalms long ago when he was recovering from a wound; he used them in times of silence or peril, and always quietness and confidence came with them. Now he ceased to trouble himself about what he should say to Prince George in the morning.

He could hear the thunder of the surf on his left. Around him was the circle of hills that crouch over Barcelona. The night was clear; it was still some hours till moonrise; the stars glittered gold against deepest blue. The splendid words rolled on:

‘The lions roaring after their prey do seek their meat from God. The sun ariseth and they get them away together and lay them down in their dens.

‘Man goeth forth to his work and his labour until the evening.

‘O Lord how manifold are thy works; in wisdom hast thou made them all; the earth is full of thy riches.’

He finished the psalm and went into the tent. He drew off his boots and within a minute was in bed. He fell asleep almost as soon as he closed his eyes.

Chapter II

Sunday

September 13th

When his servant came to shave him next morning, Colonel Awbyn at once remembered that he had to see Prince George. He still did not know what he should say if the Prince asked him why he brought his plan to the King’s adviser instead of to his own commander-in-chief. The Prince was a soldier and was sure to ask him the question, and he did not know the answer. It was a line of conduct so foreign to any he would have chosen himself that he could not imagine why anyone should do such a thing. He decided that he would have to say he thought it best because the Dutch and English generals were against a siege, and he would stick doggedly to that, unconvincing though it sounded, like a sullen prisoner before a court martial.

Shaved and dressed, he took a morning draught of a light Spanish white wine; it was a wine the quartermaster of his troop had done well to get before the vintners in San Martino had sold all their stocks. He qualified it carefully with water, for he was a moderate man and frugal, retaining those French virtues at a time when they were not admired in England. Then he sent a message to the major that he did not know when he would be back, and was just putting on his hat when his servant announced that Captain Petty wished to speak to him. He stepped out of the door to meet him.

‘I’m sorry, Petty,’ he said, ‘but I have some urgent business. If it’s the brevet, and I suppose it’s still that, perhaps it could wait?’

Captain Petty agreed that it could wait, but added politely that it had been waiting a long time and he would like to get it settled.

The colonel sighed.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘And I don’t see how it can be settled here. But before dinner I will talk it over with you and Wills and give you my decision, and that must hold till we hear further from my lord in Berlin or from the Captain-General in Flanders.’

‘Very good, Sir.’ Captain Petty left him and the colonel went on his way towards Prince George’s quarters. He had himself a brevet of colonel in the army, but he was only the lieutenant-colonel of the regiment. He was in command, but it was sometimes tiresome that he could do so little without reference to the colonel, Lord Raby, who was Her Majesty’s envoy in Berlin.

When he reached Prince George’s quarters, Colonel Awbyn found everything in a bustle. He saw an aide-de-camp and asked for the Prince in French, for his German was weak.

‘He has gone out, no one knows where,’ he was told. ‘Early this morning, milord Peterborough came, before the Prince was dressed. Milord went in to see him and in ten minutes the Prince called for a horse and the two of them went off together, with only one aide-de-camp, as friendly as could be. They have gone to look at something; no one knows what.’

Since the two generals had not spoken to each other for a fortnight, it was no wonder everyone was in a stir at this. Colonel Awbyn thanked his informant and left with a feeling of relief. Some men would have been conscious also of disappointment; an awkward task avoided, yes, but a lost chance of being at the hub of affairs, in the secrets of the great. But for Awbyn the relief was unmixed with anything but pleasure; he was delighted that the two leaders were at one again and felt a lively hope that something would come of it. He smiled at himself as he remembered how much he had disliked the commission his lordship had put upon him, how he had tried vainly to think what he should say. What had happened, he supposed, had been that the general had thought of the project all night and in the morning had been so much afire with it that he could not wait and had gone out to broach it to the Prince directly.

Awbyn drew out his watch; it was a present from Lord Raby, who held him in some esteem, as well he might, for, in addition to his pay as colonel, the regiment put a good six hundred pounds a year in the envoy’s pocket. There was still time to see the regiment drawn up for prayers, for it was Sunday. After prayers, Sunday or no Sunday, the major and adjutant would put them through the exercise; these had been Colonel Awbyn’s orders for every Sunday since the landing, for the men had nothing to do and he was a firm believer in the proverb about idle hands.

The men were in fact already drawn up when he arrived and he was content to take no part in the parade but to remain a spectator.

It was thoroughly unsatisfactory to see only half the men mounted and the rest unmounted, but there was no way out of it unless the men were to forget the mounted part of the exercise. It was the custom of the regiment to hear prayers drawn up as though for battle; that is to say, they were first drawn up mounted but left their horses linked and came forward on foot towards the chaplain, for dragoons were still mounted infantrymen and although increasingly used as horse were still a separate arm of the service. Colonel Awbyn watched with a critical eye as the major gave the words of command:

‘Dragoons, have a care.

‘Sling your muskets.

‘Make ready your links.

‘Clear your right foot of the stirrups.

‘Dismount and stand at your horses’ heads.

‘Link your horses to the left.

‘March clear of your horses and shoulder as you march.’

The men without horses on the left of each troop moved at the last order only.

‘Halt!’

Now the regiment were dismounted, in line, clear of the horses, which stood linked so that one man could hold ten. There was one thing about these Portuguese brutes; they gave no trouble when required to stand still linked.

The chaplain read prayers. Colonel Awbyn’s mind did not dwell on the words as it had done last night. He thought that considering what they had been through, and that it was two years since the last re-clothing, the men did not look bad. Coat linings and the borders of saddle-cloths and holster-caps were still recognizably blue, coats were still scarlet. The hats were the worst, and after all those months on shipboard in a Dutch port it was not surprising that they should be; indeed, it was a wonder they had not all been eaten by rats. Hats were a yearly issue, and he would see about getting new ones at the first opportunity.

His mind ran back over the past two years; the Netherlands; orders for Spain; the embarkation and that unforgettable winter weather-bound in port, cooped up on board for three and a half months from start to finish. And then, on top of all the discomfort for the officers and hardship for the men, the perpetual sickening wrangle about allowances. There was no reason on earth why they should not get the full allowance; the ship being weather-bound they might just as well have been ashore, but though everyone agreed, nothing was done. Portugal at last, not till March, and it had been November when they embarked. And after such a winter, when at last they went ashore in Portugal, they had been ordered to encamp! It would not have been so bad if there had not been good accommodation available, but to see it all taken by the brigadier for his own regiment, who were put into quarters that would have held twice as many, that really had made Colonel Awbyn angry. He grew angry again at the memory of that dispute with Harvey’s Horse and his interview with Brigadier Harvey. Horse they might be, and we only Dragoons, but we are the elder regiment, and a royal regiment at that, and we have King Charles’s proclamation that we take precedence as horse in the field and as foot in garrison. And Lord Raby is senior to Brigadier Harvey. So that we should certainly have taken precedence over Harvey’s Horse on any count.

But it was no use getting angry about that again. He watched the men again critically; prayers were finished and they were going through the musketry exercise.

‘Dragoons, have a care.’

Each man pulled off his right glove and tucked it under his waist-band. Gloves, he thought, were not suitable for this climate; they could not of course leave them off for public appearances, but for ordinary parades during the week, perhaps they could manage without them.

‘Handle your daggers.’

‘Draw forth your daggers.

They had fixed bayonets now and were charging to the right, charging to the left, as in the old pike exercise. Captain Wills’s troop was a trifle ragged; he was seeing Captain Wills anyhow about the brevet, and would mention it then. Now the bayonets were back in the scabbards and they were reloading.

‘Clean your pan.

‘Open your cartridge-box.’

It was a simple business nowadays, with flintlocks and cartridge-boxes, a dozen words of command saved since he had joined. It really had been a business then, with bandoliers and matchlocks, and wasteful of life too. For he could himself remember more than one occasion in battle when a musketeer had gone to a powder-barrel to fill his bandoliers without putting his match out and had blown up himself and half the company.

‘Blow off your loose corns.’

They had finished reloading and now came a part of the exercise which in Colonel Awbyn’s opinion should not be done too often. If it was kept for Sundays only, and those were his orders at present, the men enjoyed it and you could get some idea of whether there was anything seriously amiss with them.

‘Quit your arms.

‘March clear of your arms and break.’

The men had laid down their muskets and marched clear of them. They broke line and gathered in irregular knots. Now the drums beat a ruffle ending with a single flam, on which the men drew their swords and with a loud huzza ran to their arms as though charging an imaginary foe. Now came a second ruffle and on the final flam the men were drawn up again in their ranks, swords sheathed, muskets at the order. Not bad, the Colonel thought, not bad; but you would see them do it very differently if there was a chance of action.

He did not wait for the end of the parade but went back to his quarters to finish some correspondence before Petty and Wills should come to see him. As he went, he wondered whether the Earl and the Prince had decided to try his plan, whether perhaps that afternoon they would hear that the train of artillery was to march away to the south-east to batter that long stretch of unflanked curtain.

He was deep in a letter to his colonel, who was punctilious in requiring exact news of everything that happened in the regiment, when Captain Petty and Captain Wills came to see him. He greeted them in a friendly way, for he believed in being as informal as he could with his officers when off duty, and asked each of them in turn to explain why he thought he should take precedence over the other. He did, as a matter of fact, already know exactly what each of them would say and had made up his mind what he was going to say himself. All the same, he must hear them again, for if he did not his decision would seem arbitrary and tyrannical. So he listened attentively.

The case of Captain Wills was very simple. He had joined the regiment as a cornet two years before Petty and had served in the lieutenant-colonel’s troop until he was the second senior lieutenant in the regiment and often virtually in command of the troop. Then two vacancies for captain had occurred and Wills and the captain-lieutenant, or senior subaltern, were next for promotion. Wills had bought one of the two vacant troops from the outgoing captain for a thousand pounds. He had obtained permission to transfer to the new troop and on his colonel’s recommendation had been gazetted and commissioned captain. On a calculation, he had had ninety-two pounds back in return for discharging his predecessor of all liability for recruiting, re-mounting and re-fitting. He had had the troop now for six months and there could therefore be no question that he was senior to Petty who on the books of the regiment was the lieutenant in this same troop.

Petty had come to what was now Captain Wills’s troop as a cornet and had been duly promoted lieutenant. Then, being what Awbyn in his letters to Lord Raby always called a pretty gentleman, he had been chosen as an aide-de-camp to a general. He had been away more than two years, putting much extra work on the captain and cornet of his troop, for there was no one to take his place. While absent, he was reported to have behaved very well, and he was the only officer of the regiment who had been present at the battle of Blenheim last year. There was no doubt he had done well and the regiment were proud of him. Nor had he spoiled his good name by conceit since he came back. His good behaviour had brought him to notice and he had been rewarded with a brevet of the rank of captain under the hand of the Captain-General, the Duke of Marlborough, himself. Now his brevet stated clearly that from the date of the commission he would take precedence as a captain of dragoons not only outside his regiment but within it. And his brevet was two months older than Wills’s commission as captain, so that if the terms of Petty’s commission were followed he took precedence of the captain of his own troop.

Colonel Awbyn listened attentively and then gave his decision. He had referred the whole affair to Lord Raby whom he had asked to obtain from Mr. Cardonnel, His Grace’s secretary, orders that would make the matter clear. In the meantime a man who had a troop must take precedence over a man who had not. Captain Petty had a captain’s pay and allowances, which gave him fifteen shillings and sixpence a day instead of nine shillings as a lieutenant, and that must suffice him till he could buy a troop. But we shall have the whole trouble over again, he thought, when a troop does become vacant, for the captain-lieutenant, who commanded the colonel’s troop, was senior to Petty in the regiment and would certainly expect the vacancy. It was getting a troop that made the difference to an officer, for if too many recruits did not die or desert and he had reasonable luck with his remounts, it should be worth two hundred pounds a year beyond his pay. And the man who had stayed by the regiment felt he had a better right to a troop than the pretty gentleman who had been an aide-de-camp.

Captain Petty accepted the colonel’s decision with a bow; he was a tall man and fair, very self-possessed and easy in his manner. The three stood up and Awbyn called for wine. It was dinner-time and dinner on Sunday was something of an occasion, even when, as at present, they were dependent on what the troop quartermasters could provide. The smell of roast meat from the earth-built field kitchens was already strong and savoury in the hot air of early afternoon. Talk became general and came round to the everlasting topic of the siege.

‘Joshua was the man,’ said Captain Petty, ‘Ram’s horns and trumpets instead of a train of artillery. He made a breach in seven days, and such a breach as we could never make with modern guns, for it went right round the fortress. And look how much simpler transportation was when your battering train could be carried by your musicians.’

Everyone laughed, pleased that Petty was taking it so well. They were still laughing when Peter de Nérac joined them. He had not yet been aide-de-camp to His Majesty a fortnight and still lived with the regiment, for there were no more quarters available in the suburb of San Martino where the great men were lodged. Today it was his turn to be off duty.

‘Well, have you heard the news?’ he asked.

All three looked at him eagerly. They had heard nothing.

‘We march to Tarragona,’ said Peter. ‘The advanced guard starts today. I thought you’d have had orders, by now.’

Even at that moment, orders arrived. Awbyn told the messenger to wait and with an apology to the others broke the seal on his letter. It was from Mr. Furly, and conveyed very precisely and formally the general’s orders that a detachment of two hundred men of the Queen’s Dragoons should accompany the advanced guard on the march to Tarragona. The advanced guard were to be drawn up and ready to march by six o’clock on Sunday evening in front of Prince George of Hesse’s quarters; they were to be prepared for the possibility of action on the way; there might be a Castilian garrison in some small town. Then, with a slight change of wording, came the Earl of Peterborough’s particular request that Colonel Awbyn should command the detachment for the march, leaving Major Warren to pack up the camp and follow with the main body of the army.

Colonel Awbyn allowed himself no time to reflect on this till he had done what was necessary. He sent Captain Petty to give his orders to Major Warren; he sent for the adjutant and instructed him to have the men drawn up in the camp by five o’clock. Their cartridge-boxes were to be full and each man should have two pounds of bread in his haversack and what cheese the quartermasters could find, besides eight pounds of oats.

It was only when this was done and he sat down to dinner, that he allowed his mind to reflect on the particular request that he should accompany the advanced party. Was there perhaps some ray of hope in this? But all depended on the guns. He turned to Peter who was joining him for dinner, and asked whether he could say what orders had been given to the train of artillery. Peter understood his thought and it was with sympathy for his disappointment that he answered:

‘The battering train is to be re-embarked.’

The battering train, the heavy siege guns, would go by sea to Tarragona but the field train would of course come with the main army. Then the siege was not to be attempted; they really were to march away. Colonel Awbyn’s heart was heavy and, as the news spread, the same heaviness invaded every private soldier in the army. For whatever the strategists might say, the judgment of the soldier was that of the Catalan peasantry; the Allied army had come to take Barcelona and gone away without even trying. Either they had been fools to come or they were cowards to go; the soldier was inclined to think they were both.

But there was too much to do that afternoon for any time to be wasted on regrets. Colonel Awbyn had to leave Major Warren instructions as to what stores could go by sea and what was to follow with the main body of the army, and it was a difficult problem. For if stores were entrusted to the fleet, they might be sunk at sea or lost and never seen again, while it was still uncertain how the baggage of the main army would move because of the shortage of horses, mules and wagons. Major Warren was the kind of man who wanted exact orders, and it was very difficult to give them. He would have to use his discretion to some extent and see how much he could get on to the wagons of the baggage-train when they materialized.

Lord Raby’s troop, the lieutenant-colonel’s and two other troops were drawn up mounted at five o’clock before the camp. It had been necessary to borrow mounted men from other troops and leave behind the unmounted, all most unsatisfactory. Colonel Awbyn rode along the three ranks, checking here and there the contents of a cartridge-box or a haversack. They wheeled into fives and in a few minutes were marching at the trot to San Martino. Not that they could keep up a trot for long, the colonel gloomily reflected, and as for galloping, it was out of the question. Still, they could make a fair show for a short distance. The drums and oboes played them away, blue ribbons fluttered on the horses’ bridles, arms gleamed brightly in the afternoon sun. It was a pity that since they were unmounted there could be no question of the musicians coming with the advanced guard.

In the square in front of Prince George of Hesse’s quarters, where they must halt till six o clock, there was such a crowd of country people that it was not easy for the troops to move into their proper places. The peasants seemed to think that every dragoon had it in his power to change the orders for the march; women knelt before their horses, stretched out their arms to them and wept, caught hold of their bridles, imploring them to stay in a stream of words they did not understand.

Colonel Awbyn halted his four troops and pushed his horse through the crowd. He had to find the officer commanding the detachment of two troops of Conynghame’s Irish Dragoons that was to join them. A tall priest poured forth entreaties to him in Spanish and Latin, holding out to him and actually thrusting against his bridle hand a piece of gold plate, a tray from an altar-service; but whether for himself or the King was not clear. Colonel Awbyn thrust it away with a movement of his hand and edged his horse towards the priest so that he had to fall back. Gently, sidling at the half-passage first one way and then the other, he made his way towards the officer of Conynghame’s. He hated this; he had foreseen in his talk with the general last night what the Catalans would feel, but the reality was worse, and all the more so for being irrelevant to what he had to do. It was like having toothache when on duty; you wanted it to stop so that you could get on with the work.

He had to shout to make himself understood, but the officer of Conynghame’s was very reasonable. Although he had been first at the rendezvous, he recognized that the Queen’s as elder regiment must take the right of the line; but it was not so easy to get the men there. They were at first sorry for the people in the square, but since they liked the march no better than the peasants, they gradually became irritated and inclined to be rough. Impatience with the wretched beasts they rode added to the men’s annoyance; the officers had to get them through the crowd and across the square without hurting the country people, and because the noise was so terrific that no orders could be heard it was difficult to keep them moving and check roughness at the same time. But at last it was done, and the six troops of dragoons were drawn up in their ranks.

Behind them were drawing up four hundred grenadiers and six hundred musketeers, taken from several regiments of foot and including some Dutch. There were also some light carts with scaling ladders and ammunition. The foot were having even more difficulty than the dragoons in getting into position; Colonel Awbyn, riding across the front of his regiment to speak to the troop commanders, saw a fat major of foot struggling to free himself from a peasant woman’s arms round his neck, and the grenadiers behind him forced to use their carbines as staves to push the people back. It was the priests and the women who were most trouble; the men kept in the background, sullen and angry.

An aide-de-camp came out from the Prince’s lodgings and managed to push his way through to Colonel Allen, who commanded the detachment of musketeers. They consulted and a score of files under a captain wheeled away from the rest and, each man holding his musket before him by the butt and the muzzle, managed to clear the space in front of the parade, forming a line of men at each end to keep it clear. Into the haven thus created, horses were led; the Earl and the Prince came out and mounted and at once the order was given to move off. A trumpeter sounded the tucket, and the column moved away to the north, the crying of women growing more frenzied as they seized the muskets of the thin line of men who held them back, shaking them with all the strength of their bodies, wailing in despair as they saw their deliverers marching away, leaving them to the mercy of a sovereign for whose rule they had shown their distaste so openly.

The column wound its way north-westward into the hills. As the sun sank towards the horizon, the guns of Barcelona thundered in a joyous salute and rockets streamed their arrowy way into the night, bursting in coloured stars above the sea. The French and Castilians were rejoicing; the threat of a siege was ended; there would be a public holiday in Barcelona tomorrow.

Chapter III

The Assault on Montjuich

September 14th

The column wound its way from the market-gardens of San Martino north-westward towards the hills. Night had fallen; there were no more rockets and the guns of Barcelona were silent. It was dark and not easy to keep on the road. Peering through the gloom, leaving things as far as he could to his horse, there was not much of Colonel Awbyn’s attention available for anything else, but what thoughts he had were almost as gloomy as the night. An inconclusive and badly managed campaign in Portugal last year, and now, in spite of his lordship’s zeal and energy, divided councils and a bad beginning. Three weeks wasted in front of Barcelona and nothing to show for it. Peter might be right and a march to Madrid the better strategy, but to go away from Barcelona now meant the Catalans would never trust them again. And there would be no heart in the men, for if there was one thing that depressed them it was being endlessly moved about without purpose.

Captain Lediard, the senior captain of the regiment, commanding the third troop of the column, was occupied with thoughts not very dissimilar. He was a keen officer and he felt the regiment were not being treated fairly. They had missed the march to the Danube and the battle of Blenheim by being ordered away to Spain and so far everything that had happened here had confirmed his worst fears; an amateurish, rascally business, this Spanish war seemed to be; no horses, no wagon-master, no proper commissary of provisions, no sieges; nothing but argument and discussion. And to a man of his service, unlikely to lead to promotion; for in Flanders, he reflected grimly, a battle or a siege might carry off a dozen field officers in a day, but here the enemies that would do execution would be women, wine and green fruit. Young men’s enemies; it would be new cornets that would be needed, not majors or lieutenant-colonels.

That was the background of Captain Lediard’s thoughts, that and a perpetual slight irritation with the lieutenant that fate and Lord Raby had sent him. But the immediate question to him as to everyone else in the column was how much longer it would be before they halted. Supper and a bivouac and water, those were every man’s needs after three hours’ marching, of which the first part had been in the hot September sun. There was no point in going on like this all night; they were only an advanced guard, and the main body would certainly not start tomorrow.

At the rear of the troop, the lieutenant, Mr. Hedley, shared his troop commander’s interest in when they were going to halt. He shared too the regret of everyone in the column at leaving Barcelona, but his reasons were not those of his colonel. He was a young man of a sanguine complexion and temperament, an extremely healthy animal, and what he had looked forward to had been the fruits of a successful siege. When they got into the town, he had promised himself two things, a horse and a mistress. It was only as to the horse that he had anticipated any difficulty; Catalonia was notorious for the lack of them but surely there must be some decent horses in the capital. A man who had his eye on the governor’s stables should be able to lay his hands on something before they were all taken for the great men, and if he could have a horse that was any pleasure to ride, tills Spanish campaign might become bearable. As to his other requirement, he had been sure that would be forthcoming once they were in Barcelona, and so long as there had been some hope of meeting it his need had not been intolerable. But now that the prospect of gratification was receding, well, it had needed an effort to restrain himself from leaping from his horse in the square just now. Most of the women had been too old, but one would have suited him; his hot brown eyes had pictured the limbs, young, tender and vigorous, beneath her full peasant skirt, noted the rounded forearm and the thrust of back and loins as she tried to wrestle past a musketeer. But imagined delights were no solace to Lieutenant Hedley.

In the centre of the troop, the cornet, Mr. Francis, the latest joined officer of the regiment, was by now conscious mainly of thirst. At the beginning of the march, he had been full of excitement and anticipation; it was his first prospect of action, for there was a chance of action, even though proved soldiers from the Netherlands spoke slightingly of anything they were likely to meet. Action at last; he thought of it with a tightening of the throat, a drying of the mouth; he hoped he would be brave; he did not think he would be frightened to the extent of cowardice but he was far from sure that he would keep cool. It would be easy to do the wrong thing, to forget an order. He must keep cool and remember his men. He must not get excited, he must remember the exercise as though he were on parade. Those had been his droughts at the beginning of the march. Now he thought about water.

But as the darkness grew deeper, a suspicion had occurred to Colonel Awbyn. He was beginning to wonder whether perhaps, after all, there might not be something in the wind. He would not put it precisely into words, even to himself, but something he began to suspect there must be. He knew the country better than most; he had several times in the last three weeks ridden up into the hills to look back at Barcelona and see it as a whole, to learn where the roads led up there in case any expedition into the surrounding country became necessary. He knew they would soon be reaching the convent generally known as Gracias. That must be where they were going to halt, but why go so far? There was no point in tiring the men by a night march if they were only an advanced guard, and that to a main force which was not going to start till the day after tomorrow. And why were the Prince and the Earl both with the advanced guard? He had supposed that the Earl was coming to get away from the court and that the Prince would come with them a short way, in proof to the world of their new friendship, turning back as dusk fell; but the Prince had not turned back; he was still with the column.

A dark shape. A mounted figure was standing by the side of the road. Colonel Awbyn drew and cocked a pistol, but an English voice reassured him. An aide-de-camp from the general. The men were to halt at Gracias; there was a spring there and they could drink, water their horses and rest. They might light fires and eat their supper. Colonel Awbyn commanding the dragoons, Colonel Southwell commanding the grenadiers, Colonel Allen commanding the musketeers, and the Dutch colonel, whose name none of the English could pronounce, were to find the general as soon as they reached Gracias.

‘What about firing?’ the colonel asked. ‘Are they to scatter to get it?’

He was told that an officer and two men had gone ahead; there would be enough wood available.

The aide-de-camp had ridden beside Colonel Awbyn as he told him this. He wheeled to one side and let the column move on past him, waiting for the grenadiers. Colonel Awbyn gave his orders to the captain-lieutenant, commanding Lord Raby’s troop, who rode by his side, and then he too moved out of the stream and let the mounted men move on; he peered at the dark shapes, waiting for a break in the ranks that would tell him where the lieutenant of the major’s troop was riding. But the ranks were broken and straggling; there was no room on the narrow hill track for the five abreast formation in which the dragoons marched on parade. He had to call the lieutenant’s name till he found him.

They were near Gracias by the time he had seen all the troop commanders and stumbled back to the head of the column, taking advantage of every stretch of road that was a little wider than the rest. Then came an open space, the sound of water; a shadowy form in the starlight, an English voice, and in a few minutes they were dismounted, horses were being given a handful of oats, fires were lighted, they could drink. Awbyn saw that each troop was in place before he moved away to find the general. There was no need to hurry, for the leading files of the foot were only just coming in.

He was away some time; when at last he was back, the men had finished supper and were settling down to sleep. He called the troop-commanders together and spoke to them in a low voice for a few minutes.

‘Nothing to the men yet,’ he said when he finished. You can tell your cornets.’

Half an hour later the men were roused; sleepy, bewildered, cursing, they were on their feet, stumbling among the picket-ropes, strapping up haversacks, pulling on belts, feeling for horses’ heads, swearing at buckles. No drums, no oboes, only the sergeants’ fierce low orders.

‘Boot and saddle.’

‘Quiet there; quiet, you fool.’

‘Quickly; quick and quiet; boot and saddle. Leave the fires burning.’

Girths tight; curb-chains linked; everything present, hands in the dark patting and feeling to make sure, cartridge-box, priming-flask, sword, pistols, bayonet, firelock; mount; walk march; they were moving away from Gracias.

Awbyn waited till all six troops of the detachment had moved off, sent the adjutant once more along the line of blazing fires, making sure that no men or horses were left behind, then trotted after the men, slowly and awkwardly, pushing his unwilling horse.

West-south-west. That was their course, and by the mercy of God it was a clear night. He picked up the Bear, the Pole Star, Cassiopeia, Vega, Arcturus; he set a course, but it would be the devil of a business to keep to it in this rough country. There was a guide, but Colonel Awbyn knew better than to trust entirely to a guide.

And the devil of a business it was. For the dragoons, it was not so much the bodily exertion as the mental irritation that was tiring. They were for ever peering uncertainly ahead through the dark, for ever dismounting to reconnoitre a place that looked difficult or at which a sorry Portuguese nag had jibbed. Sometimes they found it was nothing; they could mount again and drive the brute over it with the spurs, but just as often they must lead up or down to pass a field wall among the terraced olives, the stony bank of a stream, a dangerous drop above a farm sunk in a hollow. They were moving across the grain of the country, for the streams ran down to the sea and they were marching parallel with the coast. It was always up or down. Rocky ground and dry soil; always there was the clink, clink, of horseshoes on rock, now and then a spark from the feet of the horse ahead. The night air was cool; wafting through the smell of horses in poor condition, it brought scents of dust and stone, sometimes for a few yards moisture and the aromatic fragrance of crushed mountain herbage.

Lediard suggested that the six troops might split and go on independently but Awbyn did not agree. To keep together made a long straggling line, very slow and tedious for all and worst for the men in the rear, but it was better to go like this, slowly in single file, than to be scattered all over the countryside. The men drank at every stream, but nothing quenched their thirst.

After hours of groping and stumbling in the dark, they struck a road, running right and left across the line of march, a deep stony rut between the fields which Colonel Awbyn believed must be the road he was looking for. He halted the column and sent a man out either way to look for a village. Meanwhile, he drew from his coat pocket a length of grenadier’s match which he always carried with him and, having lighted it from the lock of a pistol, blew it into a glow by which he could read his watch. It was already after three o’clock; if this was not the road they were looking for, they would be late for the rendezvous.

But it seemed probable that it was; both men were back now; the one who had gone up the road, away from the sea, had found nothing, but the other had found a village with the church on the right of the road; that must be Sejia, or at least it should be. They turned towards the sea, and filed along the road, through the silent village. A cock crew; a dog barked; a heifer lowed; no human voice disturbed the quiet; but nose would have said clearly that here was a village if they had been deaf or blind.

A lightening in the east; the faintest silver radiance, the chill sweet breath of an air from the sea. Colonel Awbyn looked at his watch again but he still could not read it without his match, and he was not going to stop to light that now. In another mile he could see; it was after four, and the waning moon was high enough now to help them. The road was a stony channel for flood-water; the feet of men and cattle had begun it, water had torn away the soil. It was deep between the fields now, sometimes narrow, descending sharply to a V-shaped bed, sometimes wider where a boulder had held up the torrent. It was the kind of road they would have sworn at heartily if that journey across country had not made them grateful for it.

Now there was a warmer colour in the east, for the sun’s dawn was only a little behind the moon. A faint suffusion of primrose, of saffron, a thin line of silver cloud gilt suddenly with fire, glowing, glowing, heating intolerably, anvil hot, to vermilion; then the sun, molten, brazen, shimmering.

They were on the brow of a hill; the road for a few hundred yards had been less steep than usual; now it took a fresh plunge downwards. But the view from the road was restricted; Colonel Awbyn gave the order to halt and himself dismounted. He climbed out of the road into a field only slightly sloping, set with olive trees. He stood in the shade of one of these trees, at the top of the bank in which the field ended, and looked about him, using a French perspective glass which he had bought from a trooper in the Netherlands.

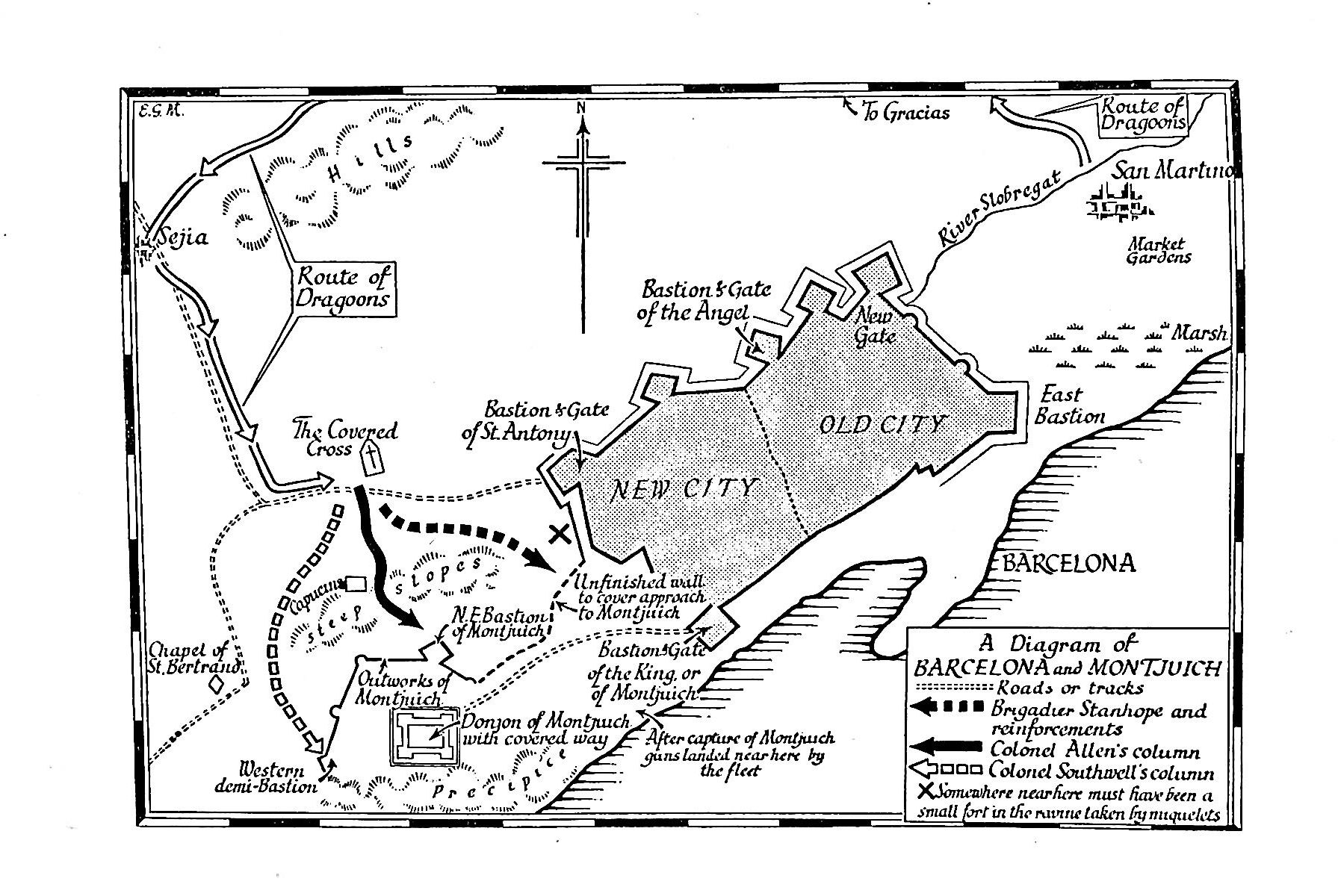

Below him the road dropped towards the sea; a little on his left lay Barcelona in the early morning sun, the first smoke beginning to rise from the chimneys, the harbour glittering sharply, for it lay right in the track of the sun, the fleet lying at anchor, tiny as toys in a bottle, dark against the more opaque water beyond. The dragoons had toiled painfully all night to make a circle of the town, and now directly before them, a little to the south of east, rose in steep escarpments the hill of Montjuich, the last bastion of the mountains. His glass found the rugged and sharply slanting line made against the sky by its western face; his circle of enlarged vision staggered up that line to the fort on the summit. There was no sign of activity there, nor in the outworks below.

He lowered the glass and looked round. The foot should not be far behind; in fact they should be up, for a horse had not been an advantage in the country they had crossed last night. And unless they were up, the plan was not going to come off. It would mean an advance of more than a mile in the open, in broad daylight, across a valley; the governor of the town would have time to send reinforcements to the fort and once it was reinforced and the garrison alert, the fort was impregnable, simply by its position. Unless the garrison was surprised or the place had been battered for weeks, no one could hope to get up that hill-side, over those sharply escarped rocks.

There was no sign of the foot on the slopes of Montjuich; they were too late and the plan would fail. With a sense of deep disappointment, he moved up the slope and a little to his left, and then he saw, away to his right, a scarlet column moving slowly and painfully over the olive terraces, down the hill, towards Montjuich. He found them in his glass; looped felt hats they wore—and he could not forbear the momentary thought that he must get his dragoons new hats as soon as this episode was over—so they must be the musketeers under Colonel Allen. They must have crossed the Sejia road in the dark and made an even longer circle than the dragoons.

He turned right away from the sea and looked behind him, searching for the tall mitre-like caps of the grenadiers. And before he had looked long, he saw them for a moment through a gap, bobbing down the same stony track from Sejia that he had followed himself.

He went back quickly to the road and gave orders. The dragoons and their horses must be out of the road quickly to let the grenadiers go by. They were to draw up in the field in which he stood, towards the back of the field, away from the sea, so that they should not be visible from Montjuich. He told the troop commanders to have the men drawn up properly, to inspect them, to see that they looked to the priming of muskets and pistols; meanwhile, he walked up the road to meet Colonel Southwell.

The colonel commanding the grenadiers was as conscious as he of the lateness of the hour. But no one could have supposed that the journey across country would have been so slow. The guides had been useless; he would have been better without them. As to my lord and the Prince, he had no news; but the instructions were exact; he knew just what he had to do. He was getting his men on now as fast as he could to join Allen and the musketeers, but it was no use pressing them too hard after such a night. Already he had lost nearly a quarter of his men as stragglers.

The grenadiers went on while this conversation took place; it could hardly be called marching, for the freshest and smartest troops in the world could not have marched in that lane. Colonel Southwell pushed on after them; Colonel Awbyn turned back to his dragoons. He made sure his troop commanders were doing their inspection properly; as soon as that was finished he wheeled them into fives as though they were on parade and sent them clattering down the lane in single file. They would get some rest, perhaps, further down the hill at the Covered Cross, which was the place appointed for them when the assault began.

The men had seen nothing from the field of olive trees, but they could see glimpses of the sea, the fort and the harbour, as they jolted painfully and tenderly down the lane. They knew now what was afoot, and, tired though they were and knowing that their own part in this affair must be secondary, excitement ran through them, they looked ahead, eager as hounds feathering at the first hint of scent.

Their station was at the Covered Cross, near the place where the road from one of the gates of Barcelona, the Gate of St. Anthony, met the road from Sejia. The place took its name from a crucifix with a covering like the roof of a lych-gate. Here, on a knoll from which they could see the slopes of Montjuich, within easy cannon-shot to the south-east, the dragoons were drawn up by troops, dismounted but not linked, standing at their horses’ heads, girths still tight, ready to mount and act as horse if required.

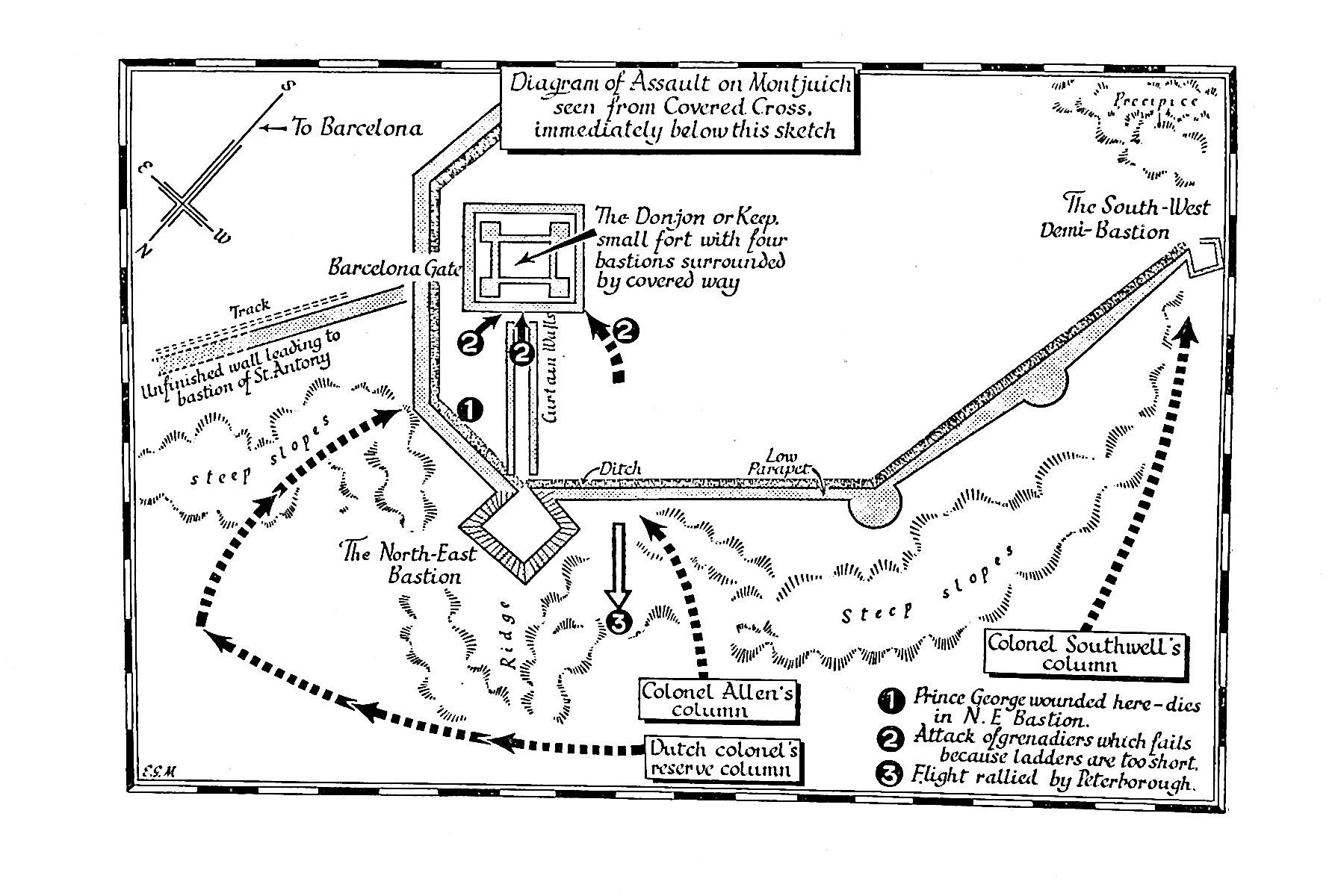

Colonel Awbyn called Captain Lediard to his side. They could see, without using the glass, the grenadiers and musketeers together at the foot of the slope. The two parties had met and halted to divide afresh for the assault. Both watchers knew the plan, so that they were able to follow, without comment, what was happening. First, two small parties left the main body of troops and began to move slowly up the hill, parallel with each other. Those would be the two parties for the first assault on the eastern and western bastions of the fort, thirty grenadiers under a lieutenant in each. Behind them, in close support of each, a second party, a little larger; that would be fifty men under a captain. Last, a larger body, two hundred musketeers, following up each of the parallel advances. Colonel Southwell was in command of the whole of the western or right-hand party, Colonel Allen of the left-hand attack. The unpronounceable Dutch colonel commanded the reserve. He should have had five hundred men, but there had been so many stragglers that he had barely half.

Colonel Awbyn’s glass raked the fort, swung northwards to the walls of Barcelona.

‘Nothing unusual,’ he said. ‘They don’t seem to have noticed.’

‘Too busy rejoicing last night,’ said Lediard.

The enemy would certainly have had headaches this morning if they had been English, Awbyn thought, but Spaniards and Italians were more abstemious. On the other hand, their mental reaction to good fortune would be more extreme. It was quite likely the guards were all playing dice. He said:

‘It may come off. I suppose that even if they had seen us, they would never have supposed till now that we were going to attack Montjuich.’

‘That’s the beauty of it,’ Lediard agreed. ‘The strongest part of the fortifications.’

There was a clatter in the lane from Sejia. The Earl and the Prince, with a knot of staff officers, must also have missed their way in the night and were trying to catch up with the battle. They did not stop; a quick word, confirming that the dragoons were stationed in the right place, and they were gone. The ground was less steep here, and they were better mounted than the dragoons; they would soon be up with the advance.

Awbyn and Lediard turned again to watch the two groups of scarlet lines creeping slowly, slowly, like the hand of a clock, up the hill before them.

‘Poor devils must be thirsty,’ said Lediard. It had been bad enough for mounted men.

Puffs of smoke just ahead of the leading scarlet figures, and the scattered sound of a dozen shots. Awbyn said:

‘Miquelets, not soldiers; I can see them running back towards the outworks.’

‘Can you see what the outworks are like?’ Lediard asked.

‘Not very well. They do not look formidable.’

They had looked at the walls of Barcelona, a dozen times. But it had been an axiom of their thought that Montjuich could not be taken and none of them had studied the fortifications. It was clear enough all the same that the strength of the place lay in the donjon, a tower and a fort with four bastions on the top of the hill. There was some kind of covered way round the donjon, and then further down the hill a line of outworks. On the side near the town, the north-east, the outworks were close to the donjon. There was a strong bastion of cut stone at this end, but the line of outworks followed the contour of the hill far away from the donjon, to the south-west, out of musket-shot. Here, the works looked slight and unfinished except for a demi-bastion at the extreme south-west.

‘It looks to me,’ said Lediard, ‘as though the outworks were too extensive. If you had enough men to hold all that outer line, it would be too many for the donjon.’

Awbyn agreed.

‘We ought to be able to get into the outworks,’ he said. ‘Then we might rush the keep, but even if we don’t, it should be possible to make things very uneasy for those who get back to it, provided always we can prevent communication with the town.’

The two triple lines of scarlet were diverging, each making for a wing of the outworks. The right-hand party would have the easier task, making for the isolated demi-bastion on the south-west. The left-hand assault on the big north-eastern bastion would soon be joined by the Prince and the Earl; the group of generals and staff officers could be seen, moving more slowly now on the steep slopes, but gaining all the same on the red lines ahead of them.

‘They’re well within musket-shot now,’ said Awbyn.

‘Enemy are holding their fire,’ said Lediard.

In another minute there were puffs of smoke from the outer line of works below the donjon. The sound of the shots reached them; but there was nothing yet from the western end. Then came firing from the western end too, a little, and sharper firing in the east. The red lines went on; there was no pausing to answer the fire; they moved slowly on, enduring their losses. They were near the works on the east.

‘They’re throwing their grenades.’