Edward Hamilton Aitken

Behind the Bungalow

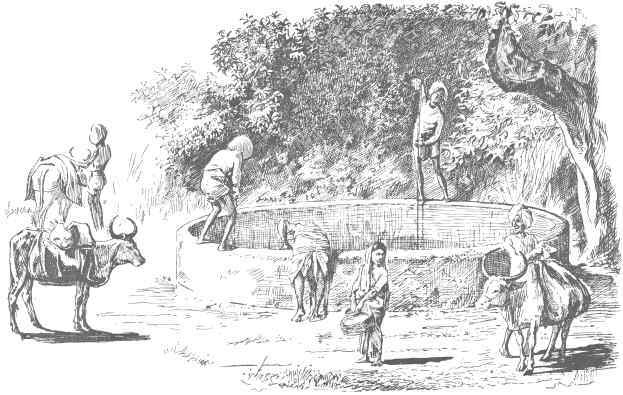

Illustrated by F. C. Macrae

Preface

These papers appeared in the Times of India, and were written, of course, for the Bombay Presidency; but the Indian Nowker exhibits very much the same traits wherever he is found and under whatsoever name.

Engaging a Boy

Extended, six feet of me, over an ample easy-chair, in absolute repose of mind and body, soothed with a cup of tea which Canjee had ministered to me, comforted by the slippers which he had put on my feet in place of a heavy pair of boots which he had unlaced and taken away, feeling in charity with all mankind—from this standpoint I began to contemplate “The Boy.”

What a wonderful provision of nature he is in this half-hatched civilization of ours, which merely distracts our energies by multiplying our needs and leaves us no better off than we were before we discovered them! He seems to have a natural aptitude for discerning, or even inventing, your wants and supplies them before you yourself are aware of them. While in his hands nothing petty invades you. Great-mindedness becomes possible. “Magnanimus Æneas” must have had an excellent Boy. What is the history of the Boy? How and where did he originate? What is the derivation of his name? I have heard it traced to the Hindoostanee word bhai, a brother, but the usual attitude of the Anglo-Indian’s mind towards his domestics does not give sufficient support to this. I incline to the belief that the word is of hybrid origin, having its roots in bhoee, a bearer, and drawing the tenderer shades of its meaning from the English word which it resembles. To this no doubt may be traced in part the master’s disposition to regard his boy always as in statu pupillari. Perhaps he carries this view of the relationship too far, but the Boy, on the other hand, cheerfully regards him as in loco parentis and accepts much from him which he will not endure from a stranger. A cuff from his master (delivered in a right spirit) raises his dignity, but the same from a guest in the house wounds him terribly. He protests that it is “not regulation.” And in this happy spirit of filial piety he will live until his hair grows white and his hand shaky and his teeth fall out and service gives place to worship, dulia to latria, and the most revered idol among his penates is the photograph of his departed master. With a tear in his dim old eye he takes it from its shrine and unwraps the red handkerchief in which it is folded, while he tells of the virtues of the great and good man. He says there are no such masters in these days, and when you reply that there are no such servants either, he does not contradict you. Yet he may have been a sad young scamp when he began life as a dog-boy fifty-five years ago, and, on the other hand, it is not so impossible as it seems that the scapegrace for whose special behoof you keep a rattan on your hat-pegs may mellow into a most respectable and trustworthy old man, at least if he is happy enough to settle under a good master; for the Boy is often very much a reflection of the master. Often, but not always. Something depends on the grain of the material. There are Boys and Boys. There is a Boy with whom, when you get him, you can do nothing but dismiss him, and this is not a loss to him only, but to you, for every dismissal weakens your position. A man who parts lightly with his servants will never have a servant worth retaining. At the morning conference in the market, where masters are discussed over the soothing beeree, none holds so low a place as the saheb who has had eleven butlers in twelve months. Only loafers will take service with him, and he must pay even them highly. Believe me, the reputation that your service is permanent, like service under the Sircar, is worth many rupees a month in India.

The engagement of a first Boy, therefore, is a momentous crisis, fraught with fat contentment and a good digestion, or with unrest, distraction, bad temper, and a ruined constitution. But, unfortunately, we approach this epoch in a condition of original ignorance. There is not even any guide or handbook of Boys which we may consult. The Griffin a week old has to decide for himself between not a dozen specimens, but a dozen types, all strange, and each differing from the other in dress, complexion, manner, and even language. As soon as it becomes known that the new saheb from England is in need of a Boy, the levée begins. First you are waited upon by a personage of imposing appearance. His broad and dignified face is ornamented with grey, well-trimmed whiskers. There is no lack of gold thread on his turban, an ample cumberbund envelopes his portly figure, and he wears canvas shoes. He left his walking-cane at the door. His testimonials are unexceptionable, mostly signed by mess secretaries; and he talks familiarly, in good English, of Members of Council. Everything is most satisfactory, and you inquire, timidly, what salary he would expect. He replies that that rests with your lordship: in his last appointment he had Rs. 35 a month, and a pony to ride to market. The situation is now very embarrassing. It is not only that you feel you are in the presence of a greater man than yourself, but that you know he feels it. By far the best way out of the difficulty is to accept your relative position, and tell him blandly that when you are a commissioner saheb, or a commander-in-chief, he shall be your head butler. He will understand you, and retire with a polite assurance that that day is not far distant.

As soon as the result of this interview becomes known, a man of very black complexion offers his services. He has no shoes or cumberbund, but his coat is spotlessly white. His certificates are excellent, but signed by persons whom you have not met or heard of. They all speak of him as very hard-working and some say he is honest. His spotless dress will prepossess you if you do not understand it. Its real significance is that he had to go to the dhobie to fit himself for coming into your presence. This man’s expectations as regards salary are most modest, and you are in much danger of engaging him, unless the hotel butler takes an opportunity of warning you earnestly that, “This man not gentlyman’s servant, sir! He sojer’s servant!” In truth, we occupy in India a double social position; that which belongs to us among our friends, and that which belongs to us in the market, in the hotel, or at the dinner table, by virtue of our servants. The former concerns our pride, but the latter concerns our comfort. Please yourself, therefore, in the choice of your personal friends and companions, but as regards your servants keep up your standard.

The next who offers himself will probably be of the Goanese variety. He comes in a black coat, with continuations of checked jail cloth, and takes his hat off just before he enters the gate. He is said to be a Colonel in the Goa Militia, but it is impossible to guess his rank, as he always wears muftie in Bombay. He calls himself plain Mr. Querobino Floriano de Braganza. His testimonials are excellent; several of them say that he is a good tailor, which, to a bachelor, is a recommendation; and his expectations as regards his stipend are not immoderate. The only suspicious thing is that his services have been dispensed with on several occasions very suddenly without apparent reason. He sheds no light on this circumstance when you question him, but closer scrutiny of his certificates will reveal the fact that the convivial season of Christmas has a certain fatality for him.

When he retires, you may have a call from a fine looking old follower of the Prophet. He is dressed in spotless white, with a white turban and white cumberbund; his beard would be as white as either if he had not dyed it rich orange. He also has lost his place very suddenly more than once, and on the last occasion without a certificate. When you ask him the cause of this, he explains, with a certain brief dignity, in good Hindoostanee, that there was some tukrar (disagreement) between him and one of the other servants, in which his master took the part of the other, and as his abroo (honour) was concerned, he resigned. He does not tell you that the tukrar in question culminated in his pursuing the cook round the compound with a carving-knife in his hand, after which he burst into the presence of the lady of the house, gesticulating with the same weapon, and informed her, in a heated manner, that he was quite prepared to cut the throats of all the servants, if honour required it.

If none of the preceding please you, you shall have several varieties of the Soortee tribe anxious to take service with you; nice looking, clean men, with fair complexions. There will be the inevitable unfortunate whose house was burned to ashes two months ago, on which occasion he lost everything he had, including, of course, all his valuable certificates. Another will send in a budget dating from the troubled times of the mutiny. From them it will appear that he has served in almost every capacity and can turn his hand to anything, is especially good with children, cooks well, and knows English thoroughly, having been twice to England with his master. When this desirable man is summoned into your presence, you cannot help being startled to find how lightly age sits upon him; he looks like twenty-five. As for his knowledge of English, it must be latent, for he always falls back upon his own vernacular for purposes of conversation. You rashly charge him with having stolen his certificates, but he indignantly repels the insinuation. You find a discrepancy, however, in the name and press him still further, whereupon he retires from his first position to the extent of admitting that the papers, though rightfully his, were earned by his father. He does not seem to think this detracts much from their value. Others will come, with less pronounced characteristics, and, therefore, more perplexing. The Madrassee will be there, with his spherical turban and his wonderful command of colloquial English; he is supposed to know how to prepare that mysterious luxury, “real Madras curry.” Bengal servants are not common in Bombay, fortunately, for they would only add to the perplexity. The larger the series of specimens which you examine, the more difficult it becomes to decide to which of them all you should commit your happiness. “Characters” are a snare, for the master when parting with his Boy too often pays off arrears of charity in his certificate; and besides, the prudent Boy always has his papers read to him and eliminates anything detrimental to his interests. But there must be marks by which, if you were to study them closely, you might distinguish the occult qualities of Boys and divide them into genera and orders. The subject only wants its Linnæus. If ever I gird myself for my magnum opus, I am determined it shall be a “Compendious Guide to the Classification of Indian Boys.”

The Boy at Home

Your Boy is your valet de chambre, your butler, your tailor, your steward and general agent, your interpreter, or oriental translator and your treasurer. On assuming charge of his duties he takes steps first, in an unobtrusive way, to ascertain the amount of your income, both that he may know the measure of his dignity, and also that he may be able to form an estimate of what you ought to spend. This is a matter with which he feels he is officially concerned. Indeed, the arrangement which accords best with his own view of his position and responsibilities is that, as you draw your salary each month, you should make it over to him in full. Under this arrangement he has a tendency to grow rich, and, as a consequence, portly in his figure and consequential in his bearing, in return for which he will manage all your affairs without allowing you to be worried by the cares of life, supply all your wants, keep you in pocket money, and maintain your dignity on all occasions. If you have not a large enough soul to consent to this arrangement, he is not discouraged. He will still be your treasurer, meeting all your petty liabilities out of his own funds and coming to your aid when you find yourself without change. As far as my observations go, this is an infallible mark of a really respectable Boy, that he is never without money. At the end of the month he presents you a faithful account of his expenditure, the purport of which is plainly this, that since you did not hand over your salary to him at the beginning of the month, you are to do so now. Q.E.F. There is a mystery about these accounts which I have never been able to solve. The total is always, on the face of it, monstrous and not to be endured; but when you call your Boy up and prepare to discharge the bombshell of your indignation, he merely inquires in an unagitated tone of voice which item you find fault with, and you become painfully aware that you have not a leg to stand on. In the first place, most of the items are too minute to allow of much retrenchment. You can scarcely make sweeping reductions on such charges as:—“Butons for master’s trouser, 9 pies;” “Tramwei for going to market, 1 anna 6 pies;” “Grain to sparrow” (canary seed!) “1 anna 3 pies;” “Making white to master’s hat, 5 pies.” And when at last you find a charge big enough to lay hold of, the imperturbable man proceeds to explain how, in the case of that particular item, he was able, by the exercise of a little forethought, to save you 2 annas and 3 pies. I have struggled against these accounts and know them. It is vain to be indignant. You must just pay the bill, and if you do not want another, you must make up your mind to be your own treasurer. You will fall in your Boy’s estimation, but it does not follow that he will leave your service. The notion that every native servant makes a principle of saving the whole of his wages and remitting them monthly to Goa, or Nowsaree, is one of the ancient myths of Anglo-India. I do not mean to say that if you encourage your Boy to do this he will refuse; on the contrary, he likes it. But the ordinary Boy, I believe, is not a prey to ambition and, if he can find service to his mind, easily reconciles himself to living on his wages, or, as he terms it, in the practical spirit of oriental imagery, “eating” them. The conditions he values seem to be,—permanence, respectful treatment, immunity from kicks and cuffs and from abuse, especially in his own tongue, and, above all, a quiet life, without kitkit, which may be vulgarly translated, nagging. He considers his situation with regard to these conditions, he considers also his pay and prospect of unjust emoluments, with a judicial mind he balances the one against the other, and if he works patiently on, it is because the balance is in his favour. I am satisfied that it is an axiom of domestic economy in India that the treatment which you mete out to your Boy has a definite money value. Ill-usage of him is a luxury like any other, paid for by those who enjoy it, not to be had otherwise.

There is one other thing on which he sets his childish heart. He likes service with a master who is in some sort a burra saheb. He is by nature a hero worshipper—and master is his natural hero. The saying, that no man is a hero to his own valet, has no application here. In India, if you are not a hero to your own Boy, I should say, without wishing to be unpleasant, that the probabilities are against your being a hero to anybody. It is very difficult for us, with our notions, to enter into the Boy’s beautiful idea of the relationship which subsists between him and master. To get at it at all we must realize that no shade of radicalism has ever crossed his social theory. “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” is a monstrous conception, to which he would not open his mind if he could. He sees that the world contains masters and servants, and doubts not that the former were provided for the accommodation of the latter. His fate having made him a servant, his master is the foundation on which he stands. Everything, therefore, which relates to the well-being, and especially to the reputation, of his master, is a personal concern of his own. Per contra, he does not forget that he is the ornament of his master. I had a Boy once whom I retained chiefly as a curiosity, for I believe he had the smallest adult human head in heathendom. He appeared before me one day with that minute organ surmounted by a gorgeous turban of purple and gold, which he informed me had cost about a month’s pay. Now I knew that his brain was never equal to the management of his own affairs, so that he was always in pecuniary straits, but he anticipated my curiosity by informing me that he had raised the necessary funds by pawning his wife’s bangles. Unthinkingly I reproached him, and then I saw, coming over his countenance, the bitter expression of one who has met with rebuff when he looked for sympathy. Arranging himself in his proudest attitude, he exclaimed, “Saheb, is it not for your glory? When strangers see me will they not ask, ‘Whose servant is that?’” Living always under the influence of this spirit, the Boy never loses an opportunity of enforcing your importance, and his own as your representative. When you are staying with friends, he gives the butler notice of your tastes. If tea is made for breakfast, he demands coffee or cocoa; if jam is opened, he will try to insist upon marmalade. At an hotel he orders special dishes. When you buy a horse or a carriage, he discovers defects in it, and is gratified if he can persuade you to return it and let people see that you are not to be imposed upon or trifled with. He delights to keep creditors and mean men waiting at the door until it shall be your pleasure to see them. But it is only justice to say that it will be your own fault if this disposition is not tempered with something of a purer feeling, a kind of filial regard and even reverence—if reverence is at all possible—under the influence of which he will take a kindly interest in your health and comfort. When your wife is away, he seems to feel a special responsibility, and my friend’s Boy, when warning his master against an unwholesome luxury, would enforce his words with the gentle admonition, “Missis never allowing, sir.”

It is this way of regarding himself and his master which makes the Boy generally such a faithful servant; but he often has a sort of spurious conscience, too, growing out of the fond pride with which he cherishes his good name, so that you do not strain the truth to say that he is strictly honest. Veracity is the point on which he is weakest, but even in this there are exceptions. My last Boy was curiously scrupulous about the truth, and would rarely tell a lie, even to shield himself from blame, though he would do so to get the hamal into a scrape.

I regret to say that the Boy has flaws. His memory is a miracle; but just once in a way, when you are dining at the club, he lays out your clothes nicely without a collar. He sends you off on an excursion to Matheran, and packs your box in his neat way; but instead of putting one complete sleeping suit, he puts in the upper parts of two, without the nether and more necessary portions. It is irritating to discover, when you are dressing in a hurry, that he has put your studs into the upper flap of your shirt front; but I am not sure it does not try your patience more to find out, as you brush your teeth, that he has replenished your tooth-powder box from a bottle of Gregory’s mixture. But Dhobie day is his opportunity. He first delivers the soiled clothes by tale, diving into each pocket to see if you have left rupees in it; but he sends a set of studs to be washed. Then he sits down to execute repairs. He has an assorted packet of metal and cotton buttons beside him, from which he takes at random. He finishes with your socks, which he skilfully darns with white thread, and contemplates the piebald effect with much satisfaction; after which he puts them up in little balls, each containing a pair of different colours. Finally he will arrange all the clean clothes in the drawer on a principle of his own, the effect of which will find its final development in your temper when you go in haste for a handkerchief. I suspect there is often an explanation of these things which we do not think of. The poor Boy has other things on his mind besides your clothes. He has a wife, or two, and children, and they are not with him. His child sickens and dies, or his wife runs away with someone else, and carries off all the jewellery in which he invested his savings; but he goes about his work in silence, and we only remark that he has been unusually stupid the last few days.

So much for the Boy in general. As for your own particular Boy, he must be a very exceptional specimen if he has not persuaded you long since that, though Boys in general are a rascally lot, you have been singularly fortunate in yours.

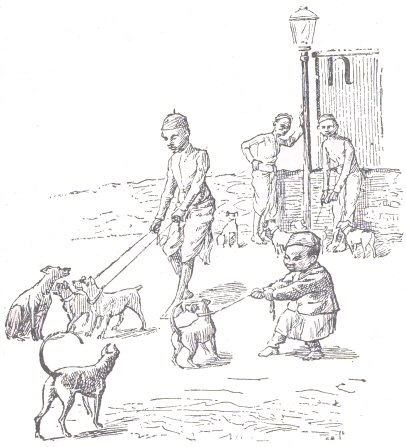

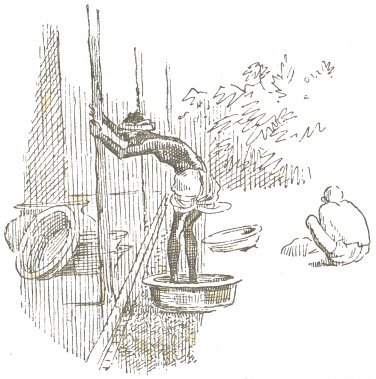

The Dog-Boy

In Bombay it is not enough to fit yourself with a Boy: your dog requires a Boy too. I have always felt an interest in the smart little race of Bombay dog-boys. As a corps, they go on with little change from year to year, but individually they are of short duration, and the question naturally arises, What becomes of them all when they outgrow their dog-boyhood? From such observations as I have been able to make, I believe the dog-boy is not a species by himself, but represents the early, or larva, stage of several varieties of domestic servants. The clean little man, in neat print jacket and red velveteen cap, is the young of a butler; while another, whom nothing can induce to keep himself clean, would probably, if you reared him, turn into a ghorawalla. There are others, in appearance intermediate, who are the offspring of hamals and mussals. These at a later stage become coolies, going to market in the morning, fetching ice and soda-water, and so on, until they mature into hamals and mussals themselves. Like all larvæ, dog-boys eat voraciously and grow rapidly. You engage a little fellow about a cubit high, and for a time he does not seem to change at all; then one morning you notice that his legs have come out half a yard or more from his pantaloons, and soon your bright little page is a gawky, long-limbed lout, who comes to ask for leave that he may go to his country and get married. If you do not give it he will take it, and no doubt you are well rid of him, for the intellect in these people ripens about the age of fourteen or fifteen, and after that the faculty of learning anything new stops, and general intelligence declines. At any rate, when once your boy begins to grow long and weedy, his days as a dog-boy are ended. He will pass through a chrysalis stage in his country, or somewhere else, and after a time emerge in his mature form, in which he will still remember you, and salaam to you when he meets you on the road. If he left your service in disgrace, he is so much the more punctilious in observing this ceremony, which is not an expression of gratitude, but merely an assertion of his right to public recognition at your hands, as one who had the honour of eating your salt. I am certain an Oriental salaam is essentially a claim rather than a tribute. For this reason your peons, as they stand in line to receive you at your office door, are very careful not to salaam all at once, lest you might think one promiscuous recognition sufficient for all. The havildar, or naik, as is his right, salutes first, and then the rest follow with sufficient interval to allow you to recognise each one separately. I have met some men with such lordly souls that they would not condescend to acknowledge the salutations of menials; but you gain nothing by this kind of pride in India. They only conclude that you are not an asl, or born, saheb, and rejoice that at any rate you cannot take away their right to do obeisance to you. And you cannot. Your very bhunghie does you a pompous salutation in public places, and you have no redress.

The dog-boy’s primary duties are to feed, tend and wash his charge, and to take it for a walk morning and evening; but he is active and very acute, and many other duties fall naturally to him. It seems hard that he should come under the yoke so early, but we must not approach such subjects with Western ideas. The exuberant spirits of boyhood are not indigenous to this country, and the dog-boy has none of them. He never does mischief for mischief’s sake; he robs no bird’s nest; he feels no impulse to trifle with the policeman. Marbles are his principal pastime. He puts the thumb of his left hand to the ground and discharges his taw from the point of his second finger, bending it back till it touches the back of the hand and then letting it off like a steel spring. Then he follows up on all fours, with the action of a monsoon frog in pursuit of a fugitive ant. But liberty and the pride of an independent position amply compensate any high-souled dog-boy for the loss of his few amusements.

I have said that the dog-boy never does mischief for its own sake. He would as soon do his duty for its own sake. The motive is not sufficient. You shall not find him refusing to do any mischief which tends to his own advantage. I grieve to say it, for I have leanings towards the dog-boy, but there is in him a vein of unsophisticated depravity, which issues from the rock of his nature like a clear spring that no stirrings of conscience or shame have rendered turbid. His face, it is simple and childlike, and he has the most innocent eye, but he tells any lie which the occasion demands with a freedom from embarrassment which at a later age will be impossible to him. He stands his ground, too, under any fire of cross-examination. The rattan would dislodge him, but unfortunately his guileless countenance too often shields him from this searching and wholesome instrument. When he is sent for a hack buggy and returns after half-an-hour, with a perplexed face, saying that there is not one to be had anywhere, who would suspect that he has been holding an auction at the nearest stand, dwelling on the liberality and wealth of his master and the distance to which his business that morning will take him, and that, when he found no one would bid up to his reserve, he remained firm and came away. Perhaps I seem hard on the dog-boy, but my experience has not been a happy one. My first seemed to be an average specimen, moderately clean and well-behaved; but he was not satisfied with his wages. He assured me that they did not suffice to fill his stomach. I told him that I thought it would be his father’s duty for some years yet to feed and clothe him, but his young face grew very sad and he answered softly, “I have no father.” So I took pity on him and raised his pay, at the same time assuring him that, if he behaved himself, I would take care of him. His principal duty was to take the faithful Hubshee for a walk morning and evening, and when he returned he would tell me where he had gone and how he had avoided consorting with other dog-boys and their dogs. When matters had gone on in this satisfactory way for some time, I happened to take an unusual walk one evening, and I came suddenly on a company of very lively little boys engaged in a most exciting game. Their shouts and laughter mingled with the doleful howls of a dozen dogs which were closely chained in a long row to a railing, and among them I had no difficulty in recognising my Hubshee. Suffice it to say that my dog-boy returned next day to his father, who proved to be in service next door. He was succeeded by a smart little fellow, well-dressed and scrupulously clean, but quite above his profession. It seemed absurd to expect him to wash a dog, so, on the demise of his grandmother, or some other suitable occasion, he left me to find more congenial service elsewhere as a dressing-boy. My next was a charity boy, the son of an ancient ghorawalla. His father had been a faithful servant, and as regards domestic discipline, no one could say he spared the rod and spoiled the child. On the contrary, as Shelley, I think, expresses it,

“He spoilt the rod and did not spare the child.”

But if my last Boy had been above his work, this one proved to be below it. You could not easily have disinfected any dog which he had been allowed to handle. I tried to cure him, but nothing short of boiling in dilute carbolic acid would have purified him, and even then the effect would, I feel sure, have been only temporary. So he returned to his stable litter and I engaged another. This was a sturdy little man, with a fine, honest-looking face. He had a dash of Negro blood in him, and wore a most picturesque head-dress. In fact I felt that, æsthetically, he raised the tone of my house. He was hardworking, too, and would do anything he was told, so that I seemed to have nothing to wish for now but that he might not grow old too soon. But, alas! I started on an excursion one night, leaving him in charge of my birds. He promised to attend to them faithfully, and having seen me off, started on an excursion of his own, from which he did not get back till three o’clock next day. I arrived at the same moment and he saw me. Quick as thought he raced upstairs, flung the windows open and began to pull the covers off the bird-cages; but I came in before the operation could be finished. In the interests of common morality I thought it best to eject him from the premises before he had time to frame a lie. About a week after this I received a petition, signed with his mark, recounting his faithful services, expressing his surprise and regret at the sudden and unprovoked manner in which I had dismissed him, and insinuating that some enemy or rival had poisoned my benevolent mind against him. He concluded by demanding satisfaction. I wonder what has become of him since.

I have said that there is a vein of depravity in the dog-boy, but there must be a compensating vein of worth of some kind, an Ormuzd which in the end often triumphs over Ahriman. The influences among which he developes do little for him. At home he is certainly subject to a certain rugged discipline; his mother throws stones at him when she is angry, and his father, when he can catch him, gives him a cudgeling to be remembered. But when he leaves the parental roof he passes from all this and is left to himself. Some masters treat him in a parental spirit and chastise him when he deserves it, and the Boy tyrannizes over him and twists his ear, but on the whole he grows as a tree grows. And yet how often he matures into a most respectable and trustworthy man!

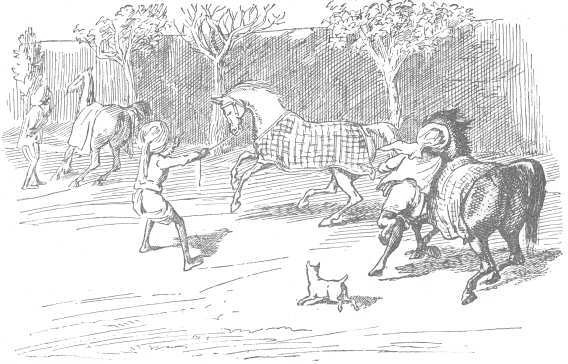

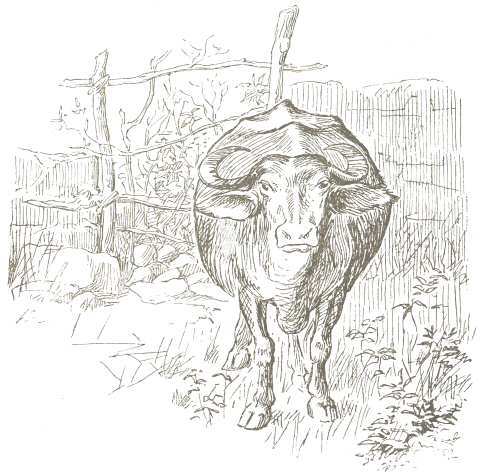

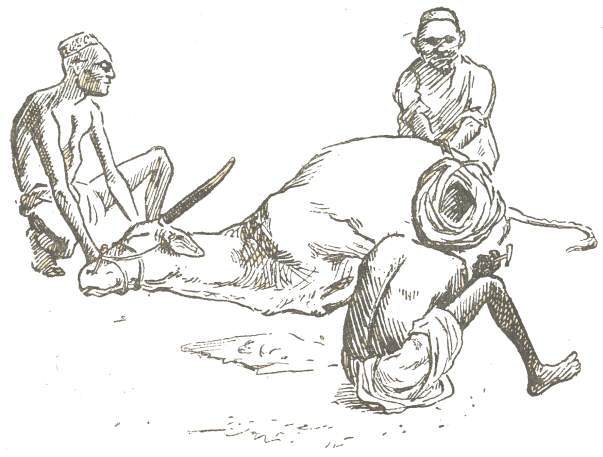

The Ghorawalla, or Syce

A boy for yourself, a boy for your dog, then a man for your horse; that is the usual order of trouble. Of course the horse itself precedes the horse-keeper, but then I do not reckon the buying of a horse among life’s troubles, rather among its luxuries. It combines all the subtle pleasures of shopping with a turbid excitement which is its own. From the moment when you first start from the breakfast-table at the sound of hoofs, and find the noble animal at the door, arching his neck and champing his bit, as if he felt proud to bear that other animal, bandy-legged, mendacious, and altogether ignoble who sits jauntily on his back, down to the moment when you walk round to the stable for a little quiet enjoyment of the sense of ownership, there is a high tide of mental elation running through the days. Then the Ghorawalla supervenes.

The first symptom of him is an indent for certain articles which he asserts to be absolutely necessary before he can enter on his professional duties. These are a jhule, baldee, tobra, mora, booroos, bagdoor, agadee, peechadee, curraree, hathalee, &c. It is not very rational to be angry, for most of the articles, if not all, are really required. Several of them, indeed, are only ropes, for the Ghorawalla, or syce, as they call him on the other side of India, gives every bit of cordage about his beast a separate name, as a sailor describes the rigging of a ship. But the fact remains that there is something peculiarly irritating in this first indent. Perhaps one feels, after buying and paying for a whole horse, that he might in decency have been allowed to breathe before being asked to pay again. If this is it, the sooner the delusion is dissipated the better. You will never have respite from payments while an active-minded syce remains on your staff. You think you have fitted him out with everything the heart of syce can desire, and he goes away seemingly happy, and commences work at once, hissing like twenty biscobras as he throws himself against the horse, and works his arms from wrist to elbow into its ribs. It looks as if it would like to turn round and take a small piece out of his hinder parts with its teeth, but its nose is tied up to the roof of the stable, and its hind feet are pulled out and tied to a peg behind it, so that it can only writhe and cultivate that amiable temper which characterizes so many horses in this country. And the syce is happy; but his happiness needs constant sustenance. Next morning he is at the door with a request for an anna to buy oil. Horses in this country cannot sleep without a night-light. They are afraid of rats, I suppose, like ladies. However, it is a small demand; all the syce’s demands are small, so are mosquitoes. Next day he again wants an anna for oil, but this has nothing to do with the other. Yesterday’s was one sort of oil for burning, this is another sort of oil for cleaning the bits. To-morrow he will require a third sort of oil for softening the leather nose-bag, and the oils of the country will not be exhausted then. Among the varied street-cries of Bombay, the “I-scream” man, the tala-chavee-walla, the botlee-walla, the vendors of greasy sweetmeats and bawlee-sugah, the legion of borahs, and that abominable little imp who issues from the newspaper offices, and walks the streets, yelling “Telleecram! tellee-c-r-a-a-m!” among them all there is one voice so penetrating, and so awakening where it penetrates, that—that I cannot find a fitting conclusion to this sentence. Who of us has not started at that shrill squeal of pain, “Nee-ee-ee-ttile!” The Ghorawalla watches for it, and stopping the good-natured woman, brings her in and submits a request for a bottle of neat’s foot oil, for want of which your harness is going to destruction. She has blacking as well as oil, but he will call her in for that afterwards. He never concludes two transactions in one day. When he has succeeded in reducing you to such a state of irritability that it is not safe to mention money in your presence, he stops at once and changes tactics. He brings the horse to the door with a thick layer of dust on the saddle and awaits your onset with the intrepid inquiry, “Can a saddle be kept clean without soap?” I suppose a time will come when he will have got every article he can possibly use, and it is natural to hope that he will then be obliged to leave you. But this also is a delusion. On the contrary, his resources only begin to develop themselves when he has got all he wants. First one of the leather things on the horse’s hind feet gives way and has to be cobbled, then a rope wears out and must be replaced, then a buckle gets loose and wants a stitch. But his chief reliance is on the headstall and the nose-bag. When these have got well into use, one or other of them may be counted on to give way about every other day, and when nothing of the original article is left, the patches of which it is composed keep on giving way. Each repair costs from one to three pice, and it puzzles one to conceive what benefit a well-paid groom can derive from being the broker in such petty transactions. But all the details of life in this country are microscopical, not only among the poor, but among those whose business is conducted in lakhs. I have been told of a certain well-known, wealthy mill-owner who, when a water Brahmin at a railway station had supplied him and all his attendants with drinking-water, was seen to fumble in his waistband, and reward the useful man with one copper pie. A pie at present rates of exchange is worth about 47/128 of a farthing, and it is instructive to note that emergency, when it came, found this Crœsus provided with such a coin.

Now it is evident that if the syce can extort two pice from you for repairs and get the work done for five pies, one clear pie will adhere to his glutinous palm. I do not assert that this is what happens, for I know nothing about it. All I maintain is that there is no hypothesis which will satisfactorily explain all the facts, unless you admit the general principle that the syce derives advantage of some kind from the manipulation of the smallest copper coin. One notable phenomenon which this principle helps to explain is the syce’s anxiety to have his horse shod on the due date every month. If the shoes are put on so atrociously that they stick for more than a month, I suspect he considers it professional to help them off.

Horses in this country are fed mostly on “gram,” cicer arietinum, a kind of pea, which, when split, forms dall, and can be made into a most nutritious and palatable curry. The Ghorawalla recognises this fact. If he is modest, you may be none the wiser, perhaps none the worse; but if he is not, then his horse will grow lean, while he grows stout. How to obviate this result is indeed the main problem which the syce presents, and many are the ways in vogue of trying to solve it. One way is to have the horse fed in your presence, you doing butler and watching him feed. Another is to play upon the caste feelings of the syce, defiling the horse’s food in some way. I believe the editor of the Aryan Trumpet considers this a violation of the Queen’s proclamation, and, in any case, it is a futile device. It may work with the haughty Purdaisee, but suppose your Ghorawalla is a Mahar, whose caste is a good way below that of his horse? I have nothing to do with any of these devices. I establish a compact with my man, the unwritten conditions of which are, that I pay him his wages, and supply a proper quantity of provender, while he, on his part, must see that his horse is always fat enough to work, and himself lean enough to run. If he cannot do this, I propose to find someone who can. Once he comes to a clear understanding of this treaty, and especially of its last clause, he will give little trouble. As some atonement for worrying you so much about the accoutrements, the Ghorawalla is very careful not to disturb you about the horse. If the saddle galls it, or its hoof cracks, he suppresses the fact, and experiments upon the ailment with his own “vernacular medicines,” as the Baboo called them. When these fail, and the case is almost past cure, he mentions it casually, as an unfortunate circumstance which has come to his notice. There are a few things, only a few, which make me feel homicidal, and this is one of them.

I cannot find the bright side of the syce: perhaps I am not in a humour to see it. Looking back down a long avenue of Gunnoos, Tookarams, Raghoos, Mahadoos and others whose names even have grown dim, I discern only a monotony of provocation. The fine figure of old Bindaram stands out as an exception, but then he was a coachman, and the coachman is to the Ghorawalla, what cream is to skim milk. The unmitigated Ghorawalla is a sore disease, one of those forms of suffering which raise the question whether our modern civilization is anything but a great spider, spinning a web of wants and their accompanying worries over the world and entangling us all, that it may suck our life-blood out. In justice I will admit that, as a runner, the thoroughbred Mahratta Ghorawalla has no peer in the animal kingdom. A sporting friend and I once engaged in a steeple-chase with two of them. I was mounted on a great Cape horse, my friend on a wiry countrybred, and the men on their own proper legs, curious looking limbs without any flesh on them, only shiny black leather stretched over bones. The goal was bakshees, twelve miles away. The ground at first favoured them, consisting of rice fields, along the bunds of which they ran like cats on a wall. Then we came to more open country and got well ahead, but at the last mile they put on the most splendid spurt I ever saw, and won by a hundred lengths.

It is also only justice to say that we do not give the Ghorawalla fair play. We artificialise him, dress him according to our tastes, conform him to our notions, cramp his ingenuity, and quench his affections. The Ghorawalla in his native state is no more like our domesticated Pandoo than the wild ass of Cutch is like the costermonger’s moke. We will have him like our own saddlery, plain and businesslike, but he is by nature like his national horse gear, ornamental, and if you let him alone, will effloresce in a red fez cap, with tassel, and a waistcoat of green baize. In such a guise he feels worthy to tend a piebald horse, caparisoned in crimson silk, with a tight martingale of red and yellow cord. He can take an interest in such a horse, and will himself educate it to walk on its hind legs and paw the air with its forefeet, or to progress at a royal amble, lifting both feet on one side at the same time, so that its body moves as steadily as if on wheels, and, to use the expressive language of a Brahmin friend of mine, the water in your stomach is not shaken. He will feed it with balls of ghee and jagree, that it may become rotund and sleek, he will shampoo its legs after hard work, and address it as “my son.” If it is disobedient, he will chastise it by plunging his knee into his stomach, and if it acquits itself well, he will plait its mane and dye the tip of its tail magenta. This loving relationship between him and his beast extends even to religion, and the horse enjoys the Hindoo festivals. During the Dussera it does not work, but comes to the door, festooned with garlands of marigold, and expects a rupee.

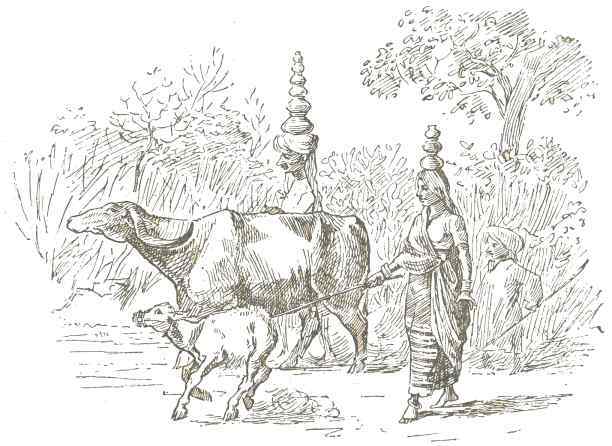

The coachman is to the Ghorawalla what cream is to skim milk, that is if you consider his substance. As regards his art he is a foreign product altogether, and I take little interest in him. There is an indigenous art of driving in this country, the driving of the bullock, but that is a great subject.

Bootlair Saheb—Anglicè, The Butler.

Some dogs, when they hear a fiddle, are forced to turn over on their backs and howl; some are unmoved by music. So some men are tortured by every violation of symmetry, while some cannot discern a straight line. I belong to the former class, and my Butler belongs to the latter. He would lay the table in a way which almost gave me a crick in neck, and certainly dislocated my temper, and he would not see that there was anything wrong. I reasoned with him, for he is an intelligent man. I pointed out to him, in his own vernacular, that the knives and forks were not parallel, that the four dishes formed a trapezium, and that the cruet, taken with any two of the salt cellars, made a scalene triangle; in short, that there was not one parallelogram, or other regular figure, on the table. At last a gleam of light passed over his countenance. Yes, he understood it all; it was very simple; henceforth I should find everything straight. And here is the result! He has arranged everything with the utmost regularity, guiding himself by the creases in the tablecloth; but, unfortunately, he began by laying the cloth itself slantwise; consequently, I find myself with my back to one corner of the room and my face to another, and cannot get rid of the feeling that everything on the table is slightly the worse for liquor. And the Butler is in despair. What on earth, he thinks, can be wrong now? He evidently gives it up, and so do I.

I have already treated of the Boy, and to devote another chapter to the Butler may seem like making a distinction where there is no difference; but there is in reality a radical difference between the two offices, which is this, that your Boy looks after you, whereas your Butler looks after the other servants, and you look after him; at least, I hope you do. From this it follows that the Boy flourishes only in the free atmosphere of bachelordom. If master marries, the Boy sometimes becomes a Butler, but I have generally seen that the change was fatal to him. He feels a share at first in master’s happiness on the auspicious occasion, and begins to fit on his new dignity. He provides himself with a more magnificent cumberbund, enlarges the border of gold thread on his puggree, and furbishes up his English that he may converse pleasantly with mem saheb. He orders about the other servants with a fuller voice than before, and when anyone calls for a chair, he no longer brings one himself, but commands the hamal to do so. He feels supremely happy! Alas! before the mem saheb has been many weeks in the house, the change of air begins to disagree with him—not with his body, but with his spirit, and though he may bear up against it for a time, he sooner or later asks leave to go to his country. His new mistress is nothing loth to be rid of him, nor master either, for even his countenance is changed; and so the Butler’s brief reign comes to an end, and he departs, deploring the unhappy match his master has made. Why could not so liberal and large-minded a saheb remain unmarried, and continue to cast the shadow of his benevolence on those who were so happy as to eat his salt, instead of taking to himself a madam, under whom there is no peace night or day? As he sits with his unemployed friends seeking the consolation of the never-failing beeree, the ex-butler narrates her ladyship’s cantankerous ways, how she eternally fidgeted over a little harmless dust about the corners of the furniture, as if it was not the nature of dust to settle on furniture; how she would have window panes washed which had never been washed before; her meanness in inquiring about the consumption of oil and milk and firewood, matters which the saheb had never stooped to look into; and her unworthy and insulting practice of locking up stores, and doling them out day by day, not to mention having the cow milked in her presence: all which made him so ashamed in the presence of the other servants that his life became bitter, and he was forced to ask for his ruzza.

Lalla, sitting next to him, remarks that no doubt one person is of one disposition and another of another disposition. “If it had been my destiny to remain in the service of Colonel Balloonpeel, all my days would have passed in peace; but he went to England when he got his pencil. Who can describe the calmness and goodness of his madam. She never asked a question. She put the keys in the Butler’s hand, and if he asked for money she gave it. But one person is of one disposition and another is of another disposition.”

“That is true,” replies the ex-butler, “but the sahebs are better than the mem sahebs. The sahebs are hot and get angry sometimes, but under them a man can live and eat a mouthful of bread. With the mem sahebs it is nothing but worry, worry, worry. Why is this so dirty? Who broke that plate? When was that glass cracked? Alas! why do the sahebs marry such women?”

Old Ramjee then withdraws his beeree from his mouth and sheds light on the subject. “You see, in England there are very few women, for which reason it is that so many sahebs remain unmarried. So when a saheb goes home to his country for a wife, he must take what he can get.”

“It is a question of destiny,” says Lalla, “with them and with us. My first wife, who can tell how meek she was? She never opened her mouth. My present wife is such a sheitan that a man cannot live under the same roof with her. I have sent her to her country ten times, but what is the use? Will she stay there? The flavour has all gone out of my life.”

And they all make noises expressive of sympathy.

The Butler being commander-in-chief of the household forces, I find one quality to be indispensable in him, and that is what the natives call hookoomut, the faculty of so commanding that other men obey. He has to control a sneaking mussaul, an obstinate hamal, a quarrelsome, or perhaps a drunken cook, a wicked dog-boy, a proud coachman, and a few turbulent ghorawallas, while he must conciliate, or outwit, the opposition headed by the ayah. If he cannot do this there will be factions, seditions, open mutiny, ending in appeals to you, to which if you give ear, you will foster all manner of intrigue, and put a premium on lies and hypocrisy; and it will be strange if you do not end by punishing the innocent and filling the guilty with unholy joy. In this country there is only one way of dealing with the squabbles of domestics and dependents, and that is the method of Gallio, who was a great man.

Besides the general responsibilities of his position as C.-in-C., the Butler has certain specific duties, such as to stand with arms folded behind you at meal time, to clean the silver, and to go to the bazaar in the morning. The last seems to be quite as much a prerogative as a duty, and the cook wants to go to law about it, regarding the Butler as an unlawful usurper. He asserts his claim by spoiling the meat which the Butler brings. Of course, there must be some reason why this duty, or privilege, is so highly valued, and no doubt that reason is connected with the great Oriental principle, that of everything a man handles or controls, somewhat should adhere to his palm; but if you ask how this principle is applied or worked out, I can only reply that that is a matter on which I believe not one of us has any information, though for the most part we hold very emphatic opinions on the subject. I am quite certain that it may be laid down for a general rule that the Butler prefers indirect to direct taxation. He certainly would not reduce salt and customs duties to pave the way for an income tax. Neither would a Viceroy, perhaps, if he had to stay and reap the fruit of his works, instead of leaving that to his successor—but that is political reflection which has no business here. The Butler, I say, wisely prefers indirect taxation and prospers. How, then, are you to checkmate him? Don’t! A wise man never attempts what cannot be accomplished. I work on the assumption that my Butler is, like Brutus, an honourable man, treating him with consideration, and fostering his self-respect, even at the cost, perhaps, of a little hypocrisy. It is a gracious form of hypocrisy, and one that often justifies itself in the end, for the man tends to become what you assume that he is. For myself, I confess that I yield to the butler’s claim to go to market, albeit I am assured that he derives unjust advantages therefrom, more easily than I reconcile myself to that other privilege of standing, with arms folded, behind me while I breakfast, or tiffin, or dine. I can endure the suspicion that he is growing rich while I am growing poor, but that argus supervision over my necessary food is like a canker, and his indefatigable attentiveness would ruin the healthiest appetite. After removing the cover from the “beefysteak” and raising one end of the dish that I may get at the gravy more easily, he offers me potatoes, and I try to overcome an instinctive repugnance to the large and mealy tuber under which he has adjusted the spoon in order to lighten my labour. After the potatoes there are vegetables. Then he moves the salt a little nearer me and I help myself. Next he presses the cruet-stand on my attention, putting the spoon into the mustard pot and taking the stopper out of the sauce bottle. I submit in the hope that I may now be allowed to begin; but he has salad or tomatoes or something else requiring attention. I submit once more and then assume my knife and fork. He watches his opportunity and insinuates a pickle bottle, holding the fork in his right hand. I feel that it is time to make a stand, so I give him one unspeakable look and proceed with my meal, whereupon he retreats and I breathe a little more freely. But no; he is at my left hand again with bread. To do him justice, he is quite willing to save me annoyance by impaling a slice on the knife and transferring it to my plate, but I prefer to help myself, which encourages him to return to the charge with butter and then jam. This looks like the end, but his resources are infinite. His eye falls on the sugar basin standing beside my teacup, and he immediately takes it up and, coming round to my left side, holds it to my nose. All this time sit I, like Tantalus, with the savoriest of Domingo’s “beefysteaks” before me and am not allowed to taste it. But I know that in every operation he is animated by an exalted sense of blended duty and prerogative, and if I could really open his mind to the thought that the least of his attentions was dispensable, his whole nature would be demoralized at once; so I endure and grow lean. Another thing which works towards the same result is a practice that he has of studying my tastes, and when he thinks he has detected a preference for a particular dish, plying me with that until the very sight of it becomes nauseous. At one time he fed me with “broon custard” pudding for about six months, until in desperation I interdicted that preparation for evermore, and he fell back upon “lemol custard.” Thus my luxuries are cut off one after another and there is little left that I can eat.

Our grandfathers used to have Parsee butlers in tall hats to wait upon them, but that race is now extinct. The Butler on this side of India is now a Goanese, or a Soortee, or, more rarely, a Mussulman. Each of these has, doubtless, his own characteristics; but have you ever stepped back a few paces and contemplated, not your own or anyone else’s individual servant, but the entire phenomenon of an Indian Butler? Here is a man whose food by nature is curry and rice, before a hillock of which he sits cross-legged, and putting his five fingers into it, makes a large bolus, which he pushes into his mouth. He repeats this till all is gone, and then he sleeps like a boa-constrictor until he recovers his activity; or else he feeds on great flat cakes of wheat flour, off which he rends jagged-pieces and lubricates them with some spicy and unctuous gravy. All our ways of life, our meats and drinks, and all our notions of propriety and fitness in connection with the complicated business of appeasing our hunger as becomes our station, all these are a foreign land to him: yet he has made himself altogether at home in them. He has a sound practical knowledge of all our viands, their substance, and the mode of their preparation, their qualities, relationships and harmonies, and the exact place they hold in our great cenatorial system. He knows all liquors also by name, with their places and times of appearing. And he is as great in action as in knowledge. When he takes the command of a burra khana he is a Wellington. He plans with foresight, and executes with fortitude and self-reliance. See him marshal his own troops and his auxiliary butlers while he carves and dispenses the joint! Then he puts himself at their head and invades the dining-room. He meets with reverses;—the claret-jug collides with a dish in full sail and sheds its contents on his white coat; the punkah rope catches his turban and tosses it into a lady’s lap, exposing his curiously shaven head to the public merriment; but, though disconcerted, he is not defeated. He never forgets his position or loses sight of his dignity. His mistress discusses him with such wit as may be at her command, and he understands but smiles not. When the action is over he retires from the field, divests himself of his robes of office and sits down, as he was bred to do, before that hillock of curry and rice.

Even good Homer nods, and I confess I am still haunted by the memory of a day when my Chief was my guest, and the butler served up red herrings neatly done up in—The Times of India!

Domingo, the Cook

I do not remember who was the author of the observation that a great nation in a state of decay betakes itself to the fine arts. Perhaps no one has made the observation yet. It is certainly among the records of my brain, but I may possibly have put it there myself. If so, I make it now, for the possibilities of originality are getting scarce and will soon disappear from the face of the earth as completely as the mastodon. The present application of the saying is to the people of Goa, who, while they carry through the world patronymics which breathe of conquest and discovery, devote their energies rather to the violin and the art of cookery. The caviller may object to the application of the words “fine art” to culinary operations, but the objection rests on superficial thought. A deeper view will show that art is in the artist, not in his subject or his materials. Perusal of the Codes of the Financial Department showed me many years ago that the retrenchment of my pay and allowances could be elevated to a fine art by devotion of spirit, combined with a fine sense of law. And to Domingo the preparation of dinner is indeed a fine art. Trammel his genius, confine him within the limits of what is commonly called a “plain dinner,” and he cannot cook. He stews his meat before putting it into a pie, he thickens his custard with flour instead of eggs, he roasts a leg of mutton by boiling it first and doing “littlee brown” afterwards; in short, what does he not do? It is true of all his race. How loathsome were Pedro’s mutton chops, and Camilo could not boil potatoes decently for a dinner of less than four courses. But let him loose on a burra khana, give him carte blanche as to sauces and essences and spicery, and all his latent faculties and concealed accomplishments unfold themselves like a lotus flower in the morning. No one could have suspected that the shame-faced little man harboured such resources. If he has not always the subtlest perception of the harmonics of flavours, what a mastery he shows of strong effects and striking contrasts, what fecundity of invention, what a play of fancy in decoration, what manual dexterity, what rapidity and certainty in all his operations! And the marvel increases when we consider the simplicity of his implements and materials. His studio is fitted with half a dozen small fireplaces, and furnished with an assortment of copper pots, a chopper, two tin spoons—but he can do without these,—a ladle made of half a cocoanut shell at the end of a stick, and a slab of stone with a stone roller on it; also a rickety table; a very gloomy and ominous looking table, whose undulating surface is chopped and hacked and scarred, begrimed, besmeared, smoked, oiled, stained with juices of many substances. On this table he minces meat, chops onions, rolls pastry and sleeps; a very useful table. In the midst of these he hustles about, putting his face at intervals into one of his fires and blowing through a short bamboo tube, which is his bellows, such a potent blast that for a moment his whole head is enveloped in a cloud of ashes and cinders, which also descend copiously on the half-made tart and the soufflé and the custard. Then he takes up an egg, gives it three smart raps with the nail of his forefinger, and in half a second the yoke is in one vessel and the white in another. The fingers of his left hand are his strainer. Every second or third egg he tosses aside, having detected, as it passed through the said strainer that age had rendered it unsuitable for his purposes; sometimes he does not detect this. From eggs he proceeds to onions, then he is taking the stones out of raisins, or shelling peas. There is a standard English cookery book which commences most of its instructions with the formula, “wash your hands carefully, using a nail brush.” Domingo does not observe this ceremony, but he often wipes his fingers upon his pantaloons. It occurs to me, however, that I do not wisely pursue this theme; for the mysteries of Domingo’s craft are no fit subject for the gratification of an irreverent curiosity. Those words of the poet,

“Where ignorance is bliss,

’Tis folly to be wise,”

have no truer application. You will reap the bliss when you sit down to the savoury result.

Though Domingo is naturally shy, and does not make a display of his attainments, he is a man of education, and is quite prepared, if you wish it, to write out his menu. Here is a sample:—

Soup.

Salary Soup.

Fis.

Heel fish fry.

Madish.

Russel Pups. Wormsil mole.

Joint.

Roast Bastard.

Toast.

Anchovy Poshteg.

Puddin.

Billimunj. Ispunj roli.

I must take this opportunity to record a true story of a menu, though it does not properly pertain to Domingo, but an ingenious Ramaswamy, of Madras. This man’s master liked everything very proper, and insisted on a written menu at every meal. One morning Ramaswamy was much embarrassed, for the principal dish at breakfast was to be devilled turkey. “Devil very bad word,” he said to himself; “how can write?” At last he solved the difficulty, and the dish appeared as “D—d turkey.”

Our surprise at Domingo’s attainments is no doubt due very much to the humble attire in which we are accustomed to see him, his working dress being a quondam white cotton jacket and a pair of blue checked pantaloons of a strong material made in jails, or two pairs, the sound parts of one being arranged to underlie the holes in the other. When once we have seen the gentleman dressed for church on a festival day, with the beaver which has descended to him from his illustrious grandfather’s benevolent master respectfully held in his hand, and his well brushed hair shining with a bountiful allowance of cocoanut ointment, surprise ceases. He is indeed a much respected member of society, and enjoys the esteem of his club, where he sometimes takes chambers when out of employment. By his fellow servants, too, he is recognised as a professional man, and called The Maistrie, but, like ourselves, he is an exile, and, like some of us, he is separated from his wife and children, so his thoughts run much upon furlough and ultimate retirement, and he adopts a humble style of life with the object of saving money. In this object he succeeds most remarkably. Little as we know of the home life of our Hindoo servants, we know almost less about that of Domingo, for he rarely has his family with him. Is he a fond husband and an indulgent father? I fancy he is when his better nature is uppermost, but I am bound to confess that the cardinal vice of his character is cruelty, not the passive cruelty of the pure Asiatic, but that ferocious cruelty which generally marks an infusion of European blood. The infusion in him has filtered through so many generations that it must be very weak indeed, but it shows itself. When I see an emaciated crow with the point of its beak chopped off, so that it cannot pick up its food, or another with a tin pot fastened with wire to its bleeding nose, I know whose handiwork is there. Domingo suffers grievously from the depredations of crows, and when his chance comes he enjoys a savage retribution. Some allowance must be made for the hardening influence of his profession; familiarity with murder makes him callous. When he executes a moorgee he does it in the way of sport, and sits, like an ancient Roman, verso pollice, enjoying the spectacle of its dying struggles.

According to his lights Domingo is a religious man; that is to say, he wears a necklace of red beads, eats fish on Fridays, observes festivals and holidays, and gives pretty liberally to the church under pressure. So he maintains a placid condition of conscience while his monthly remittance to Goa exceeds the amount of his salary. He rises early on Sunday morning to go to confession, and I would give something to have the place, just one day, of the good father to whom he unbosoms himself. But perhaps I am wrong. I daresay he believes he has nothing to confess.

One story more to teach us to judge charitably of Domingo. A lady was inveighing to a friend against the whole race of Indian cooks as dirty, disorderly, and dishonest. She had managed to secure the services of a Chinese cook, and was much pleased with the contrast. Her friend did not altogether agree with her, and was sceptical about the immaculate Chinaman. “Put it to the test,” said the lady; “just let us pay a visit to your kitchen, and then come and see mine.” So they went together. What need to describe the Bobberjee-Khana? They glanced round, and hurried out, for it was too horrible to be endured long. When they went to the Chinaman’s kitchen, the contrast was indeed striking. The pots and pans shone like silver; the table was positively sweet; everything was in its proper place, and Chang himself, sitting on his box, was washing his feet in the soup tureen!

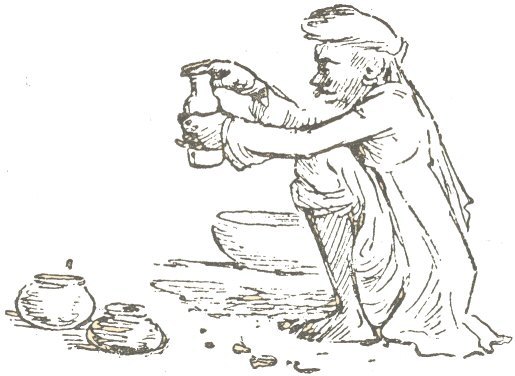

The Mussaul, or Man of Lamps

The Mussaul’s name is Mukkun, which means butter, and of this commodity I believe he absorbs as much as he can honestly or dishonestly come by. How else does the surface of him acquire that glossy, oleaginous appearance, as if he would take fire easily and burn well? I wish we could do without him! The centre of his influence, a small room in the suburbs of the dining-room, which he calls the dispence, or dispence-khana, is a place of unwholesome sights and noisome odours, which it is good not to visit unless as Hercules visited the stables of Augeas. The instruments of his profession are there, a large handie full of very greasy water, with bits of lemon peel and fragments of broken victuals swimming in it, and a short, stout stick, with a little bunch of foul rag tied to one end of it. Here the Mussaul sits on the ice numda while we have our meals, and as each plate returns from the table, he takes charge of it, and transfers to his mouth whatever he finds on it, for he is of the omnivora, like the crow. Then he seizes his weapon of offence, and, dipping the rag end into the handie, gives the plate a masterly wipe, and lays it on the table upside down, or dries it with a damask table napkin. The butler encourages him for some reason to use up the table napkins in this way. I suppose it is because he does not like to waste the dhobie on anything before it is properly soiled. When the Mussaul has disposed of the breakfast things in this summary way, he betakes himself to the great work of the day, the polishing of the knives. He first plunges the ivory handles into boiling water, and leaves them to steep for a time, then he seats himself on the ice again, and, arranging a plank of wood in a sloping position, holds it fast with his toes, rubs it well with a piece of bath brick, and commences to polish with all the energy which he has saved by the neglect of other duties. Hour after hour the squeaky, squeaky, squeaky sound of that board plays upon your nerves, not the nerves of the ear, but the nerves of the mind, for there is more in it than the ear can convey. Every sight and every sound in this world comes to us inextricably woven into the warp which the mind supplies, and, as you listen to that baleful sound, you seem to feel with your finger points the back of each good, new knife getting sharper and sharper, and to watch its progress as it wears away at the point of greatest pressure, until the end of the blade is connected with the rest by a narrow neck, which eventually breaks, and the point falls off, leaving the knife in that condition so familiar to us all, when the blade, about three inches long, ends in a jagged, square point, the handle having, meanwhile, acquired a rich orange hue. Oh, those knives! those knives!

Etymologically Mukkun is a man of lamps, and, when he has brushed your boots and stowed them away under your bed, putting the left boot on the right side and vice versa, in order that the toes may point outwards, as he considers they should, then he addresses himself to this part of his duty. Old Bombayites can remember the days of cocoanut, when he had to begin his operations during the cold season by putting a row of bottles out in the sun to melt the frozen oil; but kerosine has changed all that, and he has nothing to do but to trim the wick into that fork-tailed pattern in which he delights, and which secures the minimum of light with the maximum destruction of chimneys, to smear the outside of each lamp with his greasy fingers, to conjure away a gallon or so of oil, and to meet remonstrance with a child-like query, “Do I drink kerosene oil?” Then he unbends, and gives himself up to a gentle form of recreation in which he finds much enjoyment. This is to perch on a low wall or big stone at the garden gate, and watch the carriages and horses as they pass by. Other Mussauls, ghorawallas, and passing ice coolies stop and perch beside him, and sometimes an ayah or two, with a perambulator and its weary little occupant, grace the gathering. I suppose the topics of the day are discussed, the chances of a Russian invasion, the dearness of rice, and the events which led to the dismissal of Mr. Smith’s old Mussaul Canjee. Then the time for the lighting of lamps arrives, and Mukkun returns to his duties.

You might not perhaps suspect it, but Mukkun is a prey to vanity. The pure oily transparency of his Italian complexion commands his admiration, and he thinks much of those glossy love-locks which emerge from his turban and curl in front of his ears. Several times a day he goes into his room to contemplate himself in a small hand mirror, and to wind up the love-locks on his finger. Poor Mukkun has, indeed, a very human side, and the phenomenon which we recognise as our Mussaul is not the whole of him. By birth he is an agriculturist, and there is in the environs of Surat a little plot of land and a small dilapidated hut in one corner of it, overgrown with monstrous gourds, which he thinks of as home, sweet home. There are his young barbarians all at play, but he, their sire, is forced to seek service abroad because, as he practically expresses it, the produce of his small field is not sufficient to fill so many bellies. But, wherever he wanders, his heart—for he has a heart—flutters about that rickety hut, and as he sits polishing your boots of a morning, you may hear him pensively humming to himself:—

Beatus ille qui, procul negotiis,

Ut prisca gens mortalium,

Paterna rura bobus exercet suis,

Solutus omni fœnore.

He puts a peculiar pathos into the last line, for he is grievously haunted by an apparition in the form of an old man with a small red turban, gold earrings, and grey beard parted in the middle, who flourishes a paper in his face and talks of the debtors’ gaol; and hints that he will have the little house and field near Surat. Mukkun first fell into the net of this spider many years ago, when he wanted a few hundred rupees to enable him to celebrate the marriage of his little child. He signed a bond for twice the amount he received then, and it continues to increase from year to year, though he has paid the principal twice over in interest; at least he thinks he has, but he is not a good accountant. Every now and then he is required to sign some fresh document, of the contents of which he knows nothing, but the effect of which is always the same—viz., to heap up his liabilities and rivet his fetters more firmly, and punctually on pay day every month, the grim old man waylays him and compels him to disgorge his wages, allowing him so much grain and spices as will keep him in condition till next pay day. In a word, Mukkun is a slave. Yet he does not jump into the garden well, nor his quietus make with a bare bodkin. No, he plods through life, eats his rice and curry with gusto, smokes his cigarette with satisfaction, oils his lovelocks, borrows money from the cook to buy a set of silver buttons for his waistcoat, and when he tires of them, pawns them to pay for a velvet cap on which he has set his heart. In short, he behaves à la Mukkun, and no insight is to be had by examining his case through English spectacles; but it is our strange infirmity, being the most singular people on earth, to regard ourselves as typical of the human race, and ergo to conclude that what is good for us cannot be otherwise than good for all the world. Hence many of our anti-tyranny agitations and philanthropies, not always beneficial to the subjects of them, and also many of our misplaced sympathies. We see a spider eating a fly, and long to crush the spider, while we shed a tear for the fly. But the spider is much the higher animal of the two. It labours long hours laying out a net, and then waits all day for the fruit of its toil. Insects are caught and escape again, the net gets broken, and when, after many disappointments, the spider secures a fat fly, what advantage does it derive? A meal; just what the fly got by sitting in a pit of manure and sipping till it could sip no more. Doom that fly to the life which the spider leads, and it would drown itself in your milk jug on the spot, unable to bear up under such a weight of care and toil. In this parable the fly is Mukkun and the spider is Shylock, and my sympathies are not wholly given to the former. I quite admit that Shylock worries him cruelly, and if he had not given hostages to fortune, he would abscond with a light heart to some distant station where he might forget his old debts and contract new ones. But this is not the alternative before him. The alternative is to take care of his money, not to buy things which he cannot afford, to do without the silver buttons, and postpone the velvet cap, all which would put a strain on his mental and moral constitution, under which he would wear out in a week. He must find some other modus vivendi than that. If he had lived in the world’s infancy, he would have sold himself and his family to someone who would have fed him and clothed him, and relieved him of the cares of life. But Britons never, never, never shall be slaves, and under our rule Mukkun is forced to share that disability; so he attains his end in an indirect way, and lives thereafter in such happiness as nature has given him capacity to enjoy. Shylock will neither put him into gaol nor seize his field. We do not send our milch cow to the butcher. Shylock owns a hundred such as he, and much trouble they give him.

Mukkun lives in dread of the devil. Nothing will induce him to pass at night by places where the foul fiend is known to walk, nor will he sleep alone without a light.

The Hamal

The Hamal is a creature which gets up very early in the morning, before anyone is out of bed, and opens the doors and windows with as much noise as may be. He leaves the hooks unfastened, that a feu-de-joie may celebrate the advent of the first gust of wind. He drops the lower bolts of the doors, so that they may rake up the matting every time they are opened. Then he proceeds to dust the furniture with the duster which hangs over his shoulder. He does this because it is his duty, and with no view to any practical result; consequently it never occurs to him to look at what he is doing, and you will afterwards find curiously shaped patches of dust which have escaped the sweep of his “towal.” He next turns his attention to the books in the bookcase, and we are all familiar with his ravages there. He is usually content to bang them well with his duster, but I refer to high days, when he takes each book out and caresses it on both sides, replacing it upside down, and putting the different volumes of each work on different shelves. All this he does, not of malice, but simply because ’tis his nature to. He does not disturb the cobwebs on the corners of the bookcase, because you never told him to do so. As he moves grunting about the room, the duster falls from his shoulder, and he picks it up with his toes to avoid the fatigue of stooping. When all the dusting is done, and the table-covers and ornaments are replaced, then he proceeds to shake the carpets and sweep the floor, for it is one of his ways, when left to himself, to dust first and sweep after. Finally he disposes of the rubbish which his broom has collected, by stowing it away under a cupboard, or pushing it out over the doorstep among the ferns and calladiums.

Such is the Hamal in his youth, and as he grows older he gets more so. About middle life he sets hard, like plaster of Paris, his senses get obfuscated, and a shell appears to form on the outside of his intellect, so that access to his understanding becomes very difficult. Sometimes his temper also grows crabbed, and noli me tangere writes itself distinctly across the mark of his god on his old brow. A Hamal in this phase is the most impracticable animal in this universe. When found fault with, he never answers back, but he enters on a vigorous conversation with himself, which is like a tune on a musical box, for it must be allowed to go until it runs itself out; nothing short of smashing the instrument will stop it. How well I remember one veteran of this type, from whose colloquies with his own soul I gathered that he had been fifty-six years in gentlemen’s service, and never served any but gentlemen until he came to me. He computed his age, I think, at seventy-two, and asked leave to attend the funeral of his grandfather. Sometimes, happily, the Hamal’s senility takes the direction of benevolence. Who does not know the benign, stupid old man, with his snowy whiskers and kindly smile, which seems to grow kindlier with every tooth he loses!

It is a practical question whether you should endure the Hamal, or address yourself to the task of his reformation, and I am content to make myself singular by advocating the latter for two reasons; firstly, because he cannot be endured; secondly, because I cherish a fantastic faith in his reformability,—at least if you take him in his youth, before he has set. I believe we fail to cure him either because we do not try, or because we dismiss him before we succeed. Another great impediment to success in this enterprise is the foolish habit of getting wrathful. An untimely explosion of wrath will generally blow a sensitive Hamal’s wits quite out of his own reach, and of course, out of yours; or, if he is of the stolid sort, he will set it down as a phenomenon incidental to sahebs, but without any bearing on the matter in hand, and he will go on as before. Besides, a state of indignation is very detrimental to your own command of the language, and if you could in cold blood take your “Forbes” and study some of the sentences which you fulminated in your ebullitions of anger, you would cease to wonder that the subject of them was such an idiot.

Hum roz roz hookum day,

Tum roz roz hookum nay,

Ooswasty lukree—(whack, whack)