C. C. Dyson

From a Punjaub Pomegranate Grove

also published as

Fragments from Indian Life

Chapter I

Journey To India—Moses or Too-Too?—A Sea Post Office—The Eurasian Race—Bombay—A Narrow-Minded Englishman—A Dinner at the Pro-Consul’s

Now that I have arrived in Hariana, which is to be my headquarters for some time, I have leisure to write to you; but before I describe my present surroundings I must tell you a little of what I have seen and felt before arriving here. I want to bridge the distance that separates us, and get you to enter into my thoughts and feelings, so I am not going to write only descriptions and details of happenings, but the thoughts they arouse in me and the many interesting by-paths of history to which they show the way. I can only touch on these and give you a glimpse, as it were, of the various fields of study thus opened out; but, having shown the ways, you will be able to follow them up for yourself. When I sit down to write to you, I am going to think we are in the same room, and I am having a chat with you, so I shall put everything down as if I were talking to you. In your quiet invalid’s life I know you will enter into all, and, in spirit, live my life with me.

You know how I longed to visit the East, which I always thought of as the home of romance and mystery, where the commonplace would be left behind; but the first words I heard when the P. & O. boat anchored at the first Eastern port, Port Said, were not romantic. I was wakened at six o’clock in the morning by knocking at the cabin door.

“Who is there?”

“Cook’s man come to take Mrs. Leaver to Jerusalem.”

Mrs. Leaver was the occupant of the other berth in a two-berthed cabin, a delicate, dainty old lady with silvered hair. She looked not less than seventy years of age, but under the auspices of the courteous and capable agent of the invaluable Messrs. T. Cook & Son she started off for the Holy Land, and would travel with as much ease and comfort as if she had been a princess, and probably see a great deal more of interesting sights.

Port Said used to be full of cut-throats of all nationalities, but has greatly improved of late years. It is now safe for passengers to land, and ladies may walk about alone with impunity. All were glad to get off the boat for a few hours, and most of us spent a little money at the well-known Chinese shop, where the beautiful embroideries and eggshell china are a great temptation. On returning to the boat passengers showed their purchases, each requiring the other to guess what price had been paid. Some people coming East for the first time had been greatly imposed on by street-sellers, and had paid eight or ten shillings for bracelets of coloured stones, while others who knew the ropes had obtained the same for one shilling. The unwary ones felt greatly humbled on hearing how they had wasted their money.

In spite of a few blue-robed fellaheen in the streets, Port Said appeared to me more like an inferior French or Italian seaport than an Eastern town.

In the evening our boat started again and steamed slowly down the Canal to Suez. As we passed down the Canal we saw a few camels occasionally, and Bedouin boys ran along the banks shrieking for coppers. Some passengers responded to the appeal, and threw them, deriving amusement from the frantic efforts of the boys to find the coins in the sand. Then came a short stay at Suez, the starting-point for the Desert; it is a picturesque place, where flocks of seagulls hover round the steamers, hoping for scraps of food, and the passengers found amusement in feeding them.

Suez is attractive to the passer-by, but the English doctor at the hospital, who is an acquaintance of mine, and came to take me round the place, said: “I never heard of any one living at Suez who had the chance to live anywhere else.”

On leaving Suez we entered the Red Sea—which ought rather to be called the “Blue Sea,” so exquisitely azure are its waters. As we steamed along I looked with awe and interest at the high peaks of the barren mountains that border the sea—for one of them is Sinai. My mind was occupied with two Biblical stories which from childhood have had a place in my mental storehouse. You and I belong to a generation which in youth went regularly Sunday after Sunday to morning and evening service in our parish church, and heard one lesson from the Old Testament and one from the New at morning service, and two more in the evening. This went on year after year till quite unconsciously we had received a thorough training in Bible history—the characters seemed as well known to us as if they were members of our family, indeed we might call them familiar friends, and we should no more have thought of doubting their existence than we should have doubted our own family chronicle.

I think the young people of the present day are not as a matter of course familiar with the Bible. Just now I heard a young lady answer some one who remarked on the memories evoked by the scenes we were passing through, by saying: “Oh, I don’t know much about Moses and those old Johnnies.” And I think she missed something—as do her fellows.

Who can pass the Red Sea without thinking of Pharaoh and his hosts? The cadences of the grand old Song of Moses haunted me:

“I will sing unto the Lord, for He hath triumphed gloriously.

The Lord is a man of war.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his hosts hath He cast into the sea, even into the Red Sea.

They went down to the depths like a stone.”

I thought of Christina Rossetti’s remarks that the fate of Pharaoh and his hosts is an awful lesson against time-serving untruths.

“It was told the King of Egypt that the people fled.”

Nay, but “the children of Israel went out with an high hand” (Exodus xiv. 5).

On the supposition (apparently) that they fled, Pharaoh summoned his army and pursued them.

Who told him that they fled?

To inform him of the unvarnished truth would have been a formidable undertaking. Possibly he on whom the duty devolved softened his version of the transaction for royal ears. The Israelites were clean gone; what mattered it whether their exodus was described as a triumph or a flight?

Yet in the long run it clearly did matter, when Pharaoh and his host ended their chase, disappearing under the waters of the Red Sea. Verbal inaccuracy is often responsible for apparently incongruously big results.

I was reading again the grand old song of triumph:

“With the blast of Thy nostrils the waters were piled up,

The floods stood upright as on a heap. The enemy said, I will pursue, I will overtake. Thou didst blow with Thy wind, And the sea covered them: They sank like lead in the mighty waters, Thou didst overthrow them in the sea, even in the Red Sea,” etc.

The music of Handel’s setting of these words echoed in my mind; I went back in thought to old Handel Festival days, and seemed to see and hear our favourite tenor rising to declaim, “The enemy said,” etc.

I was humming the music softly to myself, but incongruous sounds filtered down from the upper deck where a concert rehearsal was going on.

An old young lady was singing of Miss Too-too’s adventures in France, and giving the French dandy’s greeting,

“’Ullo, Too-too, ’ow are you?” etc., and the refrain,

“Too too, too too, too,”

rang shrilly through the air.

This was followed by a young man’s voice singing:

“In Jungle Town

A big baboon

Came out to spoon

Beneath the moon,” etc.

I laughed, and gave up trying to recall ancient history. “Times are changed,” I thought as I brought my mind back to the twentieth century and went to offer my assistance to some young ladies who were struggling to get their fancy costumes finished, for most of the passengers were occupied in preparing for a fancy-dress ball which they held that evening in spite of rough and cold weather. As they tramped round the deck in procession, in order that their costumes might be judged and prizes awarded, I admired the pluck that had enabled them, in the intervals between paroxysms of sea-sickness, to take so much trouble in preparing for the ball, actuated by the wish to “ play up,” i.e. to help to keep some amusements going; though I did not admire the taste which awarded the first prize to a young lady who was disfigured by having stuffed herself out to represent a plum-pudding. The first prize for gentlemen was won by a well-known London actor, a tall faired-haired young man, who looked well as Cupid with his bow, though somewhat more stalwart than that sprite is generally supposed to have been.

On the following evening the concert took place, and the singers I had heard rehearsing were, with other performers, rapturously applauded by a crowded audience, many of whom could only find a place by sitting on the sky-lights.

As we approached Aden the weather became deliciously warm. Though anxious to escape the coaling which makes a stay at Aden, the naval Clapham Junction of the East, a necessity; we did not succeed in getting ashore. Though “the Rock,” as it is called, has a barren, uninviting appearance, it is rather a favourite station with English officers; they see a good many people, for distinguished passengers are generally landed and entertained, and excellent sport is to be had on the Somaliland side.

At Aden thirty Post-Office clerks from Bombay came on board, and, during the five days’ journey that ensued, were occupied day and night (relieving one another) in sorting the mail, so that by the time Bombay was reached the letters were all in the right sacks, ready to be despatched in the various trains that would be waiting to convey them north, south, east, and west, all over India. This Marine Post Office saves a great deal of time, as if the letters had to be sorted in Bombay there would be much delay in despatching them, and a day or two saved in the transit of letters is considered a great boon in India, especially by English residents in up-country districts, where letters are the life-belts that save them from succumbing to the depressing influence of long periods of isolation from the society of people of their own race and standing.

The Post-Office clerks were mostly Eurasians, i.e. descendants of marriages between native women and Englishmen. They are very numerous in India, but a rather isolated community, determined to dissociate themselves from the native community, yet unable to obtain recognition as equals from the English.

They fill subordinate posts on the railways and in the Police and Post Office successfully, but do not attain the standing of “Sahibs”—gentlemen—though there are a few (very few) exceptions where brilliant abilities and distinguished public services have won well-deserved success and recognition.

At Aden we left cold weather behind us finally. Warm clothing was discarded, white became the general wear, and one revelled in the delicious sensation of being thoroughly warm, through and through, without being weighed down by heavy clothing.

As we approached Bombay, the prospective brides, the young ladies going out to be married, grew nervous. There were six of them on board. Some were coming out after long engagements and wondered if they would recognise their fiancés on the quay or would find them much changed in appearance through residence in a hot climate, or whether the gentlemen would be disappointed in them, remembering perhaps a younger and fresher girl.

On this occasion all went well; the intended marriages were carried out in Bombay, except in the case of one particularly nice girl, whom no bridegroom came to meet. She had confided in me during the voyage and told me that she had her wedding-cake and wedding-dress on board, but just before the steamer started from London a telegram was handed to her on deck saying: “Do not come. Marriage must be postponed.”

Her friends were seeing her off and she could not make up her mind to communicate the substance of the telegram to them, nor to stay behind at the last moment; so she remained on board and throughout the passage was very miserable and depressed. After reaching Bombay she went up-country to friends, from whose house the wedding was to have taken place. I have since heard that after some delay it did take place, for the friends were influential, and the bridegroom was told it was too late to draw back. She has taken a risk, but whether the marriage will turn out better or worse than the general run, time alone can show.

Many amusing stories are told of the meetings, after some years have elapsed, of engaged couples. It has happened that an expectant bridegroom has been told by his fiancée on landing that his hopes are not to be fulfilled, that the lady has met on board some one she prefers, and intends to marry. I heard of a young man who had been living for a long time in a country district in India and not seen much of recent European fashions, who was so disgusted at the costume in which his fiancée landed at Bombay that he told her he could not possibly marry a girl who made such a guy of herself.

One such contretemps between disillusioned engaged couples has been most amusingly dealt with in Mrs. Croker’s very clever novel, “The Catspaw,” which I advise you to get, if you have not already read it.

A drive through the streets of Bombay, with its crowd of dark faces of many races wreathed in turbans of every shape and hue, and the picturesque dress of the numerous Parsees, the tall stiff black hat of the men, and the gracefully draped sarees of exquisitely coloured silks worn by the women, made one feel that at last Europe was left behind.

Next evening there was a dinner-party at Government House, where the King’s representative lives in becoming state. On this occasion an Englishman of no importance distinguished himself by taking away his wife before dinner. As soon as the aide-de-camp had gone round and told the gentlemen whom they were to take in to dinner, the one in question found that his wife was to be taken in by a Parsee gentleman, a cultured man with Western manners, who had spent much time in Europe and assimilated all that was best there, and whose munificent gifts for the public welfare had been rewarded with a title. To the narrow-minded Englishman, this estimable gentleman was only a “nigger,” not worthy to take his wife in to dinner, so he ordered his carriage and took her away to avoid this indignity, as it appeared to him. Needless to say, the couple never received another invitation to Government House.

Now I have assured you of my safe arrival, and written enough for one mail. You must wait till next week to hear more.

Chapter II

In The South Mahratta Country—A Durbar—A College Prize-Day—A Maharajah’s Banquet— A Hindu Lady’s “Trazu” Ceremony

After leaving Bombay I went to pass a few days with an old friend at Kolhapur, in the South Mahratta Country. The ascent of the Western Ghauts to Poona is a wonderful bit of engineering, and lovely views are to be had as the train winds slowly uphill, and one can look down at the green valleys with silver streams running through them; they are studded too with villages, which look so very far below us. By the time we reached Poona it was dark, and after changing carriages, the boy prepared my bed, and I settled down to sleep, for we were to travel all night and reach Kolhapur at seven next morning.

As soon as dawn broke, I awoke, and found we were passing through a flat agricultural country with wide roads bordered by trees, and, early as it was, the country people were on the move, women were at the wells drawing water for the day’s use, others with bundles on their heads were marching steadily along behind their men-folk to market or to some temple.

The Indian woman of the working class always walks behind her husband and carries whatever has to be carried.

At Kolhapur Station my friend met me with a little covered wagonette (called a dhummie) drawn by two bullocks with very long horns, who trotted along at a smart pace, while the driver pulled their tails instead of using a whip.

“Here at last is a little local colour,” I thought.

Ten minutes’ drive brought us to my friend’s comfortable bungalow, where chota hazri (morning tea and toast), brought by a handsome white-robed Mohammedan “boy,” was very welcome, as was also the hot bath which followed, though the large zinc washing-tub, which was the bath I was to use, was a novelty in the way of baths, but I afterwards found it in universal use throughout India.

I may here explain that “boy” is the term applied in Western India to all indoor servants, even if they are grey-headed.

Chota hazri, little breakfast, was followed by a regular breakfast at half-past ten. After answering questions about mutual friends at home, I found that there was quite a programme of social events to be got through in the next few days. That night a dinner at the Residency, next morning a College speech and prize function, third day a Durbar, fourth a banquet at the Palace.

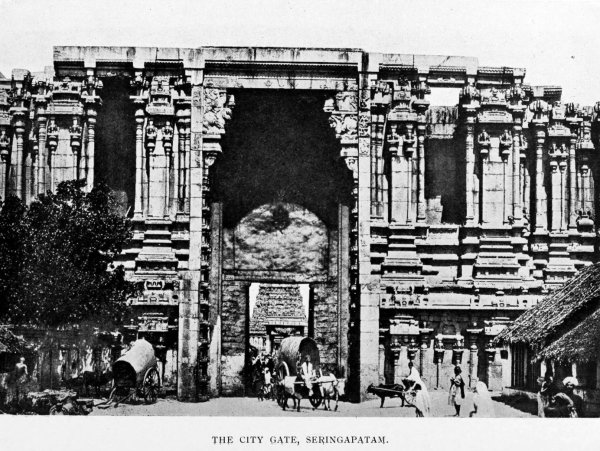

Kolhapur is off the main line of travel generally taken by globe-trotters when they visit India, and is not so well known as it deserves to be. As a Sacred City, Hindus consider it second only to Benares. They say that the gods put both cities in the scale, and that Benares weighed down Kolhapur by an almost imperceptible degree. The temple of the Goddess Ambedévi in the heart of the city is highly venerated. The great bell which sounds the hours of prayer must once have been in a Roman Catholic church, for it has the Virgin’s name engraved on it. Only very great and important non-Hindu persons are allowed even to look inside the Temple into the Holy Place, though one is allowed to walk about the outer courts, which are occupied by small stall-holders selling the things needed for offerings to the gods. Once a Governor of the Bombay Presidency expressed a wish to see the inside, so a scaffold and platform were erected on which he had to mount to look over a rampart or wall into the inner court. What he saw is not on record. To reach this temple you have to go through the heart of the city into its tight-packed native quarters, through crowded streets so narrow that there is not room for one vehicle to pass another, and a puttiwala1 has to run before the carriage shouting to the people to get out of the way.

There are beautiful silks and stuffs to be bought in the shops, and when we entered one to make a purchase, the whole street seemed to take an interest in the affair—some of the people entered the shop, others crowded round the entrance looking on and commenting.

There are few English residents in Kolhapur—only the Political Agent and his assistants, the Commandant of the native regiment, the Principal of the Maharajah’s College, and home missionaries. There are also some American missionaries, who are always counted as Europeans.

Now I must tell you about our dinner-party at the Residency, the Political Agent’s house—a lovely house in lovely grounds. The anteroom between the drawing-room and dining-room was filled with our host’s hunting and shooting trophies. I do not know how many full-sized stuffed panthers and tigers with fangs showing grinned at us as we passed through. A visitor newly arrived who chanced to enter the place at dark and alone might easily get a shock. Our host and hostess were entertaining some high officials. At noon I had noticed the carriages of many Indian gentlemen rolling up to the Residency, for it is their duty to call on the Resident’s guests. The dinner-table was beautifully decorated with pink lotus—the Indian water-lily. The repast was excellent, and while we partook of it the band of the Native Infantry Regiment discoursed sweet music on the verandah, into which all doors were open, playing airs from the latest operas and musical comedies then being performed in London. This band is quite celebrated, and has won several prizes at competitions in various parts of the country. Though the bandsmen are Mahrattas, the bandmaster, as usual, was a Goanese. The Goanese are a mixed race, descendants of native women married to the Portuguese settlers at Goa, the only Indian possession now left to Portugal, which gave us Bombay as the dowry of Catharine of Braganza, wife of Charles II.

Throughout India you find the Goanese as bandmasters and—cooks! They have these two talents, music and the culinary art. The best cooks are always Goanese.

On leaving the dinner-table the ladies were joined in the drawing-room by some young Indian chiefs, in statu pupillari, whose States are near Kolhapur and who are being educated there, under the eye of the Political Agent, by an English tutor. They were handsome young fellows, set off to advantage by their fine brocaded coats, diamond or pearl necklaces, and rainbow-hued turbans, or picturesque hats.

By their headgear you can tell to which caste a native of India belongs. The hat worn by a Mahratta gentleman differs in shape from that worn by a Brahmin, and turbans are folded in a great variety of styles which are in use by different castes, the profession of turban-folder being recognised as respectable. These young chiefs were generally dignified and impassive in demeanour, but they forgot to keep this up when games began.

It is very usual in India to play games after dinner. “Dum crambo” is a favourite; blowing a feather across a tablecloth held up by people sitting in a circle on the floor, is another; but what the young chiefs liked best were the guessing games. One of the company went out of the room, and the others thought of an object which he was to guess, and when the object thought of was a certain stone in the waist-buckle of a lady not present, the guessing it seemed rather a miraculous feat. Then there was a game of thinking of a celebrated man or woman, a letter of whose name was allotted to each player, who had to choose another personage with a name beginning with the letter allotted to him. The guesser had by a series of questions to elucidate the name of each personage selected. One man, whose letter was N, chose Noah, and as he described him as an Asiatic sailor it seemed improbable that that definition would enable the guesser to place him, but he succeeded in doing so.

At half-past ten the band played “God save the King!” while the young chiefs stood at the salute, and then we all took our departure.

Next day was speech-day at the Maharajah’s College, which is generally known as the Rajaram College, being named after the young Rajah, who died while on a tour in Europe. A memorial erected to him may be seen at Florence, where his death took place.

The Camp at Kolhapur, where the English reside, is some way from the College, which is in the city. It is a picturesque drive from one to the other. The road is shaded by fine trees; on either side were bright green rice-fields or patches of tall waving Indian corn, and as we crossed the bridge over the river some big monkeys were jumping up and down the parapets. The road was crowded with carts, camels, and foot passengers—beggars were lying at the side, wailing, writhing, contorting their bodies, exhibiting their sores or defective limbs in order to excite the pity of passers-by. I admired the beautiful manners of a stately elephant laden with grass for the Palace. Horses generally take fright at elephants, so the orders are that the latter have to get out of the way when a carriage comes in sight. My friend and I were in a little one-horse victoria, pigmies compared to the elephant, but as soon as the mahout2 perceived us he made the elephant understand, and the huge creature backed sedately up a very steep bank to get off the road and well out of our way. He looked at us out of his small eyes, seeming to understand the situation so well: “Behold, why should they fear me? I should do them no harm. They are as dwarfs and I a giant. I could take them up in the carriage, together with the horse and driver, and throw them aside out of my way as easily as a child throws a ball.”

As we approached the city we found it was taking a holiday and treating the day as a gala-day. Shopkeepers and friends in best clothes were sitting at the shop-doors, and the streets were lined with crowds of people waiting to see their Maharajah and the Sahibs (English gentlepeople) pass along to the Rajaram College, where the boys of Kolhapur State get a good education at the Maharajah’s expense.

The Maharajah drove up escorted by his Body Guard; and the Political Agent, with his guests, had a little escort of Sowars (mounted men carrying spears with pennons attached).

When we entered the College hall, the Sahibs took their seats in the front rows, while the Maharajah, the Political Agent, and the guest of honour, the visiting Governor, who was to present the prizes and make a speech, sat on the platform.

The Principal of the College, who wore a very crumpled black gown, read out his annual report, after which some boys gave recitations in correct but rather laboured English. The visitor made his speech and then a long procession of boys went up to receive their prizes at his hands. While this went on, my thoughts wandered away to the place and the day when I had last seen that handsome and distinguished specimen of the genus Englishman who does his country’s work abroad.

If it is true that “where our thoughts are, there are we,” I was not in India among a crowd of dark faces framed in brilliant coloured turbans, the whole bathed in glorious sunshine. I was in London, in St. Paul’s Cathedral, on a cold, grey spring day, and the occasion was the dedication of a side Chapel for the use of the Knights of St. Michael and St. George.

King Edward and the (then) Prince of Wales had come in state, and though the Chapel is small, the function was very impressive.

The Knights Grand Cross wore magnificent long flowing mantles of blue satin lined with red, and had gigantic stars on their breasts.

The King and his son both wore the same blue mantles as the Knights Grand Cross. All the Knights met them at the door and followed in procession to the Chapel, which has beautiful old carved oak stalls. A short service was held there, then the procession went up the nave to the choir, where the rest of the service was held, a short sermon and some beautiful hymns. The bells of St. Paul’s clashed an accompaniment to the hymns, and as they have a beautiful soft tone the effect was most moving. From my seat in the nave I had a good view of the proceedings. Everything had been so carefully rehearsed that there was not a hitch, no one hurried, no one was at a loss where to go or what to do, all moved quietly and impressively. This was due in great measure, I think, to the fact that nearly all the members of the Knightly procession were fairly old, and bore the impress in their faces of lives spent in good work, and duty done, self not the mainspring of their existence.

Only one of the procession was undignified, an old Grand Cross, a short man whose mantle was too long for him, so he clutched it up in front of him like an old dowager going upstairs at a ball and determined not to tread on her best dress at any price.

To come back to India, no one is a better judge of a “gentleman” than the Indian people. A real Sahib is the same as a real gentleman, and you may hear a servant say: “No, I shall not take the place, he is only a low-class Sahib.” And ladies are described as “first and second class ladies.” When first the Indian Civil Service was opened to competitive examination there were many murmurs in India. “Are we to be governed by any low-caste Sahib who can pass an exam.? In old days the Sahibs were Sahibs.” On this occasion they felt very sure that the distinguished Englishman now speaking to them was a first-class Sahib and listened with great attention to the good advice he gave them.

The Rajaram College is a picturesque building in the Indo-Saracenic style. After the ceremony was over, the Principal took us up to the flat roof, from whence we had a lovely view over Kholapur and the environs.

It is beautifully situated on rising ground which affords a lovely view over the surrounding country. A fine river winds through the outskirts of the city, which is embowered in trees, and the many temples and tombs rising from encircling groves add to its picturesqueness. Then the bathing-ghauts on the bank of the river are always crowded with people bathing or washing clothes; a little farther on, smoke is rising from the burning-ghauts, where corpses are cremated. One could look right away beyond the city to the Maharajah’s New Palace, and not far from it is the pretty little English church, built by the celebrated Bishop Douglas at a time when there was always an English regiment quartered in the Camp.

The banquet is to be held at the New Palace, the Durbar to-morrow at the Old Palace in the city.

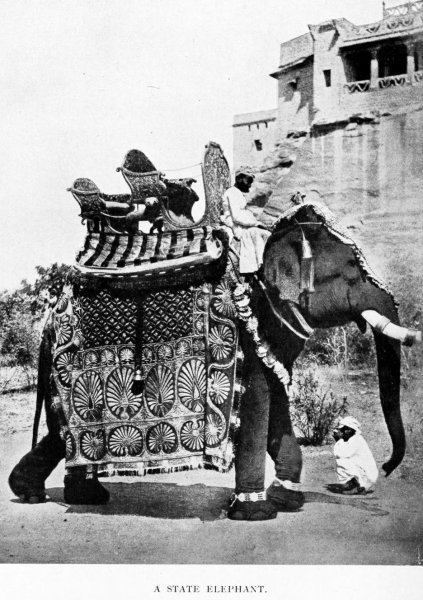

I was lucky to see a real Eastern ceremony, a Durbar, so soon after my arrival in India. When we arrived at the Palace gate, we saw that a guard of Native Infantry was stationed in the Palace Square. There, too, the gorgeously caparisoned State elephants were standing, and a fine white charger, to whose saddle was affixed the gilded, bejewelled Sacred Umbrella which the Maharajah alone has a right to, and from which he takes his title, “Maharajah Chatrapatti” or “Maharajah of the Umbrella,” chatra being the Mahrathi word for “umbrella.”

When we entered the Durbar Hall the seats were already filled with Indian gentlemen, each in his allotted place, the position of which marks his social standing, and is of vast importance in his eyes.

We were received at the entrance by some State officials and guided to seats at the top of the hall near the daïs, on the side allotted to English visitors. Soon after we took our seat the blare of trumpets announced the arrival of the Maharajah, the Political Agent, and the distinguished visitor.

Heralds preceded them up the hall, calling out the Maharajah’s titles. As representative of the King-Emperor the Political Agent at State functions always sat on a sofa beside the Maharajah on the daïs, and it was an important point of etiquette that they should both take their seats simultaneously. Had the Maharajah sat down first it would have been an act of discourtesy to the representative of the Paramount Power. They were both old hands at such functions, so they stood for a moment in front of the State sofa, looked at each other, and then took their seats with successful precision.

The Durbar was held in order that two young chiefs of States feudatory to the Maharajah of Kolhapur, who had just come of age, should be invested with powers to rule their States and should do homage to the Maharajah as overlord. The proceedings began by the Dewan (Prime Minister) of Kolhapur reading out a statement of the size of the respective States and their revenues. Then each young chief in turn read out a declaration of his loyalty to his overlord, the Maharajah, and to the British Government, and paid a tribute to the advantages received from education by an English tutor. Then they knelt down and did homage to the Maharajah by touching his feet with their foreheads, and also placed some gold coins at his feet. When they rose up, one of the State officials handed each a very handsome dress—called poshak—presented by the Maharajah. Then they returned to their seats, and the Political Agent made a speech congratulating them and telling them what was expected of them in the future.

When the speech was ended, the ceremony of “garlanding” began. The Dewan brought two long necklaces, as long as a muff-chain, composed of tuberoses punctuated at certain distances by little bunches of pink roses, all held together by silver wire. The Maharajah put one round the Political Agent’s neck, and then round that of the distinguished visitor, after which the Dewan and his satellites proceeded to do the same to each English person present. They brought long-necked silver bottles containing scent, and one had to hold out one’s handkerchief, which was then sprayed with the scent and a dab of very strong scented powder was put with a little silver trowel on the back of the hand, then the garland was hung round the neck; in the case of ladies wearing very large hats it was a difficult matter, and the Indian gentlemen whose task it was smiled discreetly. To each lady, besides the garland a pair of bracelets made of flowers was given.

This ceremony took some time, and while it was going on, a nautch-girl with her musicians took their places at the lower end of the Durbar Hall and gave a performance. It was not dancing, but shuffling the feet a few yards to one side and then to another—her dress and postures were modesty itself compared with the performance one sees on the European stage; but the song that she droned out in nasal, shrill tones, was, I believe, an impassioned love song, which those who knew the language might think improper; but nobody seemed to pay the least attention to it or to the performer. She was not a young woman, and I thought the saddest part of the affair was that she was accompanied by an understudy, a little girl about eight or ten years old, who, after the older woman had sung a verse and stopped, took up the same strain and made the same movements of arms held out in impassioned appeal, etc., and one felt sorry to think that she was being initiated so young into the profession of nautch-girl and all it implies.

After the garlanding was completed, the Maharajah and the Political Agent and the distinguished visitor departed in pomp and state. Then we lesser folk filed out, and as we stood waiting for our carriages at the entrance we were the object of plain-spoken but not unfriendly comment from the crowd. My friend, who knows the language, said the remarks were amusing and to the point.

We went home to rest a while, then came tea, and my friend had time to tell me of the worry her head-butler was causing. She had offended him the previous day by “cutting” some of his charges—i.e. refusing to pay some of the overcharges in his weekly account—so he had come this morning and shown her a telegram saying that his father was dying and he must go home at once.

This is a favourite device of Indian servants when they want to leave suddenly. They get some one to send them a telegram saying that their relatives are dead or dying. Though the employers feel very sceptical as to the truth of such statements, they cannot in the case of a father’s death refuse leave, because to perform the burial ceremonies for a dead father is the first duty of the Hindu. Many a Hindu, who has no desire to marry again but has no son, takes a second wife solely for the purpose of begetting a son to perform his burial ceremonies.

My friend said that a respectable elderly man of her acquaintance recently brought a nice bright young wife to introduce to her. He had been married quite a short time, so my friend congratulated him. But he said ruefully: “She will be a great deal of trouble! But what could I do? I must have a son to perform my funeral ceremonies!” It is thought that the performance of certain ceremonies by a son after death ensures the salvation of the dead.

To return to the butler in question. My friend asked him to wait at all events till he heard his father was actually dead. But the man refused; he intended to leave at all costs at once to put his mistress to as much inconvenience as possible, knowing that she had visitors and was giving some parties and wished everything to go on smoothly.

Indian natives make excellent servants and are often really devoted, so long as you do not interfere with their peculations. When you do, you are “a low-caste Sahib,” and they do not care to stay with you. If their wages are raised it makes no difference, they will cheat over the bills just the same; they seem to think it a duty to lose no chance of doing so.

My friend and hostess had been struggling to acquire the Marathi language spoken in Western and Central India by hundreds of thousands of people, but her servants did not encourage her efforts. Marathi is one of the best and purest Indian languages, but contains many pitfalls for students, many of the words being so alike in sound that the beginner is often betrayed into cruel mistakes.

Of the two Marathi words beyduk and buduk, one means “ frog,” the other “duck.”

I was present one morning when the cook came to take his orders for the day, and his face was inimitable as he asked if his mistress really wanted frogs for dinner. Nor shall I forget the astonished face of a servant’s child (we were visiting the mother, who was sick) when my friend told him that she would put him “in a bottle”—for two Marathi words, kopee and kopree, mean respectively “bottle” and “corner,” and she had used the wrong one.

Here they still tell the story of the zealous Bishop who in the midst of varied duties had struggled to acquire a knowledge of the people’s language. In Marathi mendré is “sheep” and manzer means “ cat.” Intending in his address to a congregation of native Christians to quote “All we like sheep have gone astray,” he used the wrong word and said “All we like cats have gone astray.”

The Indian people are so phlegmatic that no titters were heard among the congregation. They gazed unmoved at the preacher, and most of them knew what he meant. The next Bishop did not attempt Marathi. He always preached in English, but an interpreter, an Indian priest, stood beside him and repeated each sentence in Marathi, after the Bishop had delivered it in English. I think this was the better plan. I was present on one such occasion, and a very stately, impressive figure the Bishop made, in his red robes, holding the pastoral staff in his hand as he stood on the chancel-steps with the white-robed priest, his interpreter, beside him.

This priest had great command of language and turned the English sentences into Marathi without faltering for a moment.

Now I must tell you about the banquet which we attended next evening. It took place in the New Palace, which is about a mile-and-a-half from the city and near the Camp, as the part where English officials live is called. The Palace is a handsome building, erected for the Maharajah’s predecessor by a French architect. On this occasion the façade was brilliantly illuminated. When we arrived at the flight of steps which lead to the entrance-hall we were greeted by the courteous Dewan, who shook us warmly by the hand, and then another official conducted us to the room where the Political Agent and his wife received the guests, acting for the Maharajah, who would not appear at the banquet till dessert was placed on the table, for it would have been breaking his caste to partake of a repast including meat dishes, or even to sit at table while others were eating.

I heard that the Maharajah’s predecessor had not been quite so particular; he would sit at table with his guests and partake of the viands other than meat.

On one occasion he was heard, during a lull in general conversation, to say to the English gentleman who was sitting next him: “Now you must tell me which things are ‘beastly’”— meaning, that as he was not much used to the appearance of dishes dressed in European style, he desired to be warned which contained the flesh of animals, so that he might not partake of it inadvertently.

The European residents in Kolhapur are not many, and every one of them had received invitations to the banquet, as had also the American missionaries, who were classed as “Europeans,” that definition being understood to include all who were not natives of India. We soon filed in to dinner, which was laid in a fine hall, the windows of which are filled with painted glass, and the niches around the walls with statues depicting the exploits of Shivajee, the celebrated ancestor of the Maharajah of Kolhapur.

I was taken in to dinner by a Parsee, one of the masters at the College. The Parsees are thoroughly Western in manner of life and outlook. I found this one very agreeable. He had been a student at Oxford, and had spent his vacation in getting some experience of the efforts at social reform being made in some of the worst London slums by College Settlements. He is the only Oriental I have ever met who has interested himself in such matters. He confided to me that he was a disappointed man, describing himself as a “Failed Indian Civil.” He had tried to pass into the Indian Civil Service, but, failing, had been obliged to take up teaching as a profession—and in this he was very successful. The examination for the Indian Civil Service is so very difficult that even to have tried to pass it and failed seems to be considered as conferring some sort of distinction on a man.

In Indian newspapers one often sees advertisements couched in the following terms:

“Wanted a B.A. or ‘Failed Indian Civil.’”

So apparently a “Failed Indian Civil” has his own particular status.

To return to the banquet. The menu was a very good one, and the repast well served, much as one might find at a good London hotel. When dessert was placed on the table, the Maharajah was announced, and the Political Agent went to the door of the hall to receive him and conduct him to the seat next his own.

After a few minutes the Maharajah rose, and, in excellent English, said how pleased he was to welcome the distinguished official, and indeed all the guests, and proposed the King’s health, which toast was warmly responded to.

Then the distinguished visitor proposed the Maharajah’s health. This toast was duly honoured, and then the company all joined in singing “For he’s a jolly good fellow,” started by the English Durbar surgeon.

After this we left the table, the Maharajah escorting the visiting official’s wife, and others following in due order of precedence; we adjourned to a room where a number of native musicians were squatting, prepared to give a concert. Although it is claimed that Indian music is very abstruse, and that Indian musicians have discovered an extra tone to the scale, yet to outsiders their performance is so monotonous and unmelodious that it is not enjoyed by Europeans. We soon grew restless and asked permission to pass on to another room where some conjurers were waiting to give proofs of their skill. Their performance was really exciting and amusing, so we were quite sorry when the Political Agent’s wife thought it time to take her departure, for we were in duty bound to follow her example. This is the etiquette of Anglo-Indian society; no one dare leave before the most important lady present has gone, and it is not thought good taste to linger long after her departure.

The Maharajah stood at the entrance and shook hands with all his departing guests, and we drove away feeling that we had been well entertained, and wishing that our drive home would last longer than it did, for the air was soft, the moon and stars brilliant, and the cicada were holding a concert in the trees, through the branches of which the fire-flies danced and gleamed.

Next day my hostess, knowing how desirous I was to see something of the manners and customs of the Indian people, took me out to a Native State about two hours’ journey by rail from Kolhapur, to be present at the “Trazu” ceremony for which the Dowager Chieftainess—great-grandmother of the present-day Chief—had sent invitations. She was a well-known old lady, one of the old school, and in her day had had much influence over the countryside and among neighbouring chiefs, most of whom were related to her. Trazu is the Marathi word for “scale.”

A pair of large scales had been prepared, on one of which the lady was to sit, and the other was to be heaped up with gold pieces equalling her weight, and the money was afterwards to be distributed in charity.

To give away their weight in silver is an act of devotion not infrequently performed by Indian ladies of rank and wealth; but to give away their weight in gold is not within the means of many, and is thought a notable event. The old lady in question was of an ancient Brahmin family and had decided to celebrate her eightieth birthday in this fashion. She had been a widow many years, and, in accordance with the Hindu law for widows, only took one meal a day. She was short, small, and very thin, and must have been a light weight. A large concourse of spectators had assembled in the wada, and we had all taken the places allotted to us, when she came in, clothed in a plain white saree, such as all widows wear, and took her seat on the scale. Some priests droned out mantras while she sat there, and gold coins were heaped up on the other side. Native musicians beat drums and sang her praises until the scale tipped down, and then the old lady stepped out and went to a seat in the verandah, where we all went to speak to her in turn.

Two girls waving peacock-feather fans stood behind her chair.

She told us that some of the money would be spent in giving a dinner to the poor of the State, but a good deal was to be sent to institutions carried on for the benefit of poor Hindus.

After having paid our compliments to her, we were scented and garlanded and then took our departure.

I leave and go north to-morrow, having greatly enjoyed my stay here, seeing and hearing much that was new to me, and my pleasure has been enhanced by the delicious warmth, and the comfort of being able to wear light clothing. No more red noses, chattering teeth, stone-cold feet such as were my daily portion in London, no more necessity for wearing two pairs of stockings and two vests one over the other. Also it is very nice to find that functions and expeditions can be arranged without any anxiety as to whether they will be stopped or spoiled by weather, because for eight months in the year one can be sure of having no rain.

These are advantages not to be despised.

I must now close this week’s budget.

Chapter III

Journey to Hariana—Bhopal—Gwalior—Agra

Here I am at last in Hariana. I had to pass three days and two nights in the train to get here, but my servant made up a comfortable bed for me each night, by spreading a rezai (soft wadded quilt) along the seat, adding three pillows for my head and a blanket for the early morning, for after midnight it grows cold. I had booked my seat in advance in a through train, so I knew I should not be disturbed. I was travelling first class, which few people do in India, and I and one other lady had the carriage to ourselves all the way to Agra, and were very comfortable on our respective sides of the carriage. The journeys are so well arranged for in India. A train always stops somewhere between 7 and 8 a.m. at a station where tea is ready, and white-robed servants hand up to the window a tempting chota hazri—a pot of really good tea, with milk and sugar, and some toast and butter, and generally fruit as well. This is very refreshing. In India it is impossible to get on without early tea, it seems necessary to set the machine going for the day.

Once, up North, when the train was crowded and the station servants over-driven, I was in danger of not getting served, and appealed to the guard.

“The train shall not go on till you have had your tea, madam; I will see to it,” he assured me!

During the morning a guard will look in to inquire if you want lunch or dinner at certain stations; if you do, you will find yourself eating a good meal of several courses in company of fellow travellers of many sorts, either at a railway station or in restaurant-car attached to trains on many lines.

On the first evening after leaving Bombay I noticed that all the trees seemed to have red leaves, but was told that it was merely because they were covered with locusts, who were devouring every scrap of vegetation in the region we were passing through. As it grew dusk many locusts came through the windows into our carriage. These mischievous creatures are very handsome, like very large Indian-red dragon-flies.

After the first night, the train continued to roll on through rural India, and on these long journeys one gets to understand what a rustic, pastoral race the bulk of the Indian people are. There was not one town of any size between Bombay and Agra, a night and a whole day’s journey in an express train. As one fares onward through long stretches of sparsely populated country, one gets glimpses of the life of the people—the ploughman, using a plough of a pattern that is hundreds of years old; the goatherd; the water-drawer, urging his oxen to and from the well; the bird-scarer, perched amid a field of grain on a little straw seat elevated on four poles, we fear often giving way to the desire to sleep, but rising up fitfully to shout and wave his arms to scare the bird-thieves away; and we see a little girl, whose head does not reach much beyond their tails, driving some huge buffaloes with formidable long horns, to drink at a pond or stream, and notice that they yield docile obedience to the stick with which their little mistress drives them; and we see the women seated at the door of the huts and hear them singing as they grind the corn or sift the rice,

One realises how remote their lives and thoughts are from the modern world, and can understand how, through the black days of the Mutiny, the mass of the people were quite unaffected by it, and continued to sow and reap and tend their flocks and herds without any other thoughts than as to how the crops would turn out, and if they would get out of the moneylender’s clutches or a bad harvest would oblige them to go deeper into his debt. It is said that some country people never even heard of the Mutiny or understood it. Or, if they heard of it, said: “What have we to do with soldiers’ quarrels?—we have enough to do to ‘fill our stomachs.’”

This rather inelegant expression is always in the mouths of poor Indian people. If convicted of an offence or a theft, the excuse always is that they were obliged to do it “to fill,” etc. If, as is customary, a servant is told he will be fined for a breakage, or some neglect of duty, the reply is invariably: “Beat me, but do not take away the means to fill,” etc.

Glimpses of village life bring many passages of Scripture to mind. Through an open barndoor one sees an ox tied to a pole, patiently pacing round and round in a circle, treading out the corn—“Thou shalt not muzzle an ox that treadeth out the corn.”

Then, when two women are grinding corn, they sit opposite each other over a small grindstone, each holding one end of the grinder, which they push backward and forward, and are in very close proximity to each other—“Two women shall be grinding at a mill, one shall be taken and the other left.”

And so on. We realise that village people in India have not changed their mode of life and work since patriarchal times.

On the second day of my journey we passed through the State of Bhopal, whose rulers are such loyal adherents of the British flag. The Government of Bhopal is an anomaly, the ruling house being Mohammedans, while the bulk of their subjects are Hindus. The hereditary powers are on the female side, Bhopal being always ruled by a Begum (Queen) whose husband is only a Prince Consort,3 and we do not hear that the wives are at all anxious to delegate their powers to their husbands or that the latter wish to seize them.

I remember hearing that at the first Durbar (held when Lord Lytton was Viceroy) the Begum of Bhopal of that day rather spoiled her otherwise magnificent appearance by wearing a knitted woollen comforter round her neck, almost hiding her splendid necklace. She had begun to wish to learn the ways of English ladies and had probably learned to knit, or, if the comforter was not her own work, some member of her family had made it for her, and it was an achievement of which she was proud. The present Begum is well known at the English Court.4 She is really a ruler and makes her authority felt in every department in the State Government. She considers that her subjects are backward in education (this is the case with the whole Mohammedan community as compared to Hindus), and not long ago issued her fiat that they were to take steps to improve in this respect, and announced that if they did not quickly take advantage of the facilities of education afforded by the State, she would know the reason why—and give them cause to regret it.

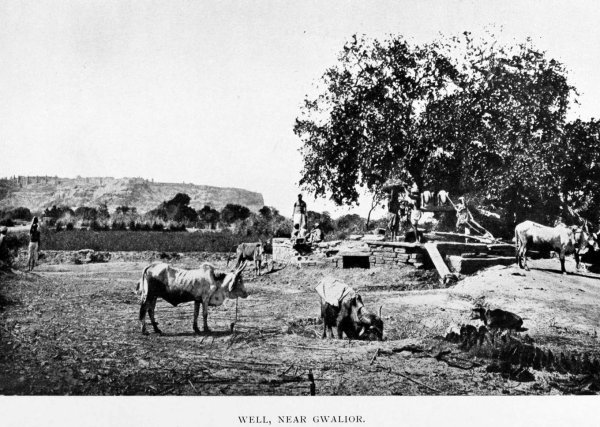

After leaving Bhopal, the next interesting place we came to was Gwalior, the fortress-city on its high rocky plateau, standing up boldly against the sky—a conspicuous object from the plains that surround it.

Its Maharajah, Scindia, is a personal friend of King George, and has entertained him twice with great splendour, and has been able to give him splendid sport, such as the King really enjoys.

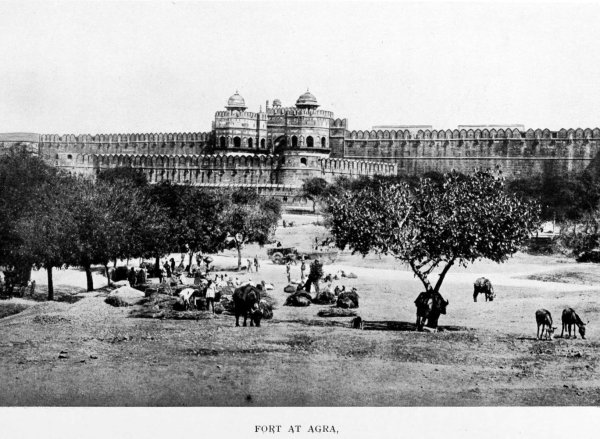

Scindia comes of a fine race. Though the Mahrattas held out longer than any other race against English rule in India, since their allegiance was given they have been loyal subjects or allies of the Crown. We owed a great deal to the Scindia of Mutiny times (the present Maharajah’s ancestor); he it was who, riding into Agra at the head of his troops at a time when the English garrison was hard-pressed by the mutineers, arrived just in time to turn the scale in our favour, and save Akbar’s Fort from falling into the hands of the mutineers.

I reached Agra as it was growing dusk, and was to leave the main line there, and rest for a day before going by a branch line to our quarters in Hariana. I had time to see that Agra, with its fine river, grand old fort, and splendid palaces and mosques embowered in green groves, is the most interesting and thoroughly Oriental city that I have yet visited in India. I had not time to see half or a quarter of its interesting sights, but I visited the old Red Fort, where, since Akbar’s days, Englishmen have done doughty deeds, and I thought of the handful shut up there in the black days, looking out, like Sister Anne, across the plains, hoping to descry a cloud of dust heralding the approach and the first waving pennons of the Lancers of Scindia’s Relief Force. If he came too late the little band of Englishmen shut up in the Fort must take desperate measures, blow up the Fort and perish in its ruins, rather than that they and their wives should fall into the hands of the mutineers. But Scindia came in time to avert such a catastrophe.

Of course I visited the Taj Mahal. I will not attempt to describe it, but will only say that of the World’s Wonders which I have seen the Taj is the only one that has not disappointed me. Its beauty far exceeds anything I could have imagined.

I was astonished at the effect the first sight of it had on my “boy,” the servant who carried my cloak and umbrella. He was an ignorant country fellow from the Bombay hill-country (my head servant had gone on to get things ready at Hariana), and such people are generally most apathetic and impassive, but to my amazement, as we passed through the outer gateway and caught the first glimpse of the white marble Taj at the end of the avenue of cypress-trees, with the stream flowing between, he dropped my chattels and threw up his arms, exclaiming “Ari, Ari, sundr, eraloqui!” (“Oh, what beauty; it is heaven!”).

He was quite overwhelmed.

As I was thinking about this in the evening at my hotel, I remembered that Canon Barnett used to say: “True beauty, anything perfectly beautiful, appeals even to the most uncultured minds.” He persuaded wealthy collectors to lend their best pictures for exhibition in Whitechapel, and was apparently justified in his idea by the results of the plebiscite always taken at the exhibition. Those who came to see the pictures were the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, the most thickly populated part of East London. Each was required to vote for the picture he or she liked best, and the pictures considered “the best” by connoisseurs always got the most votes. The real beauty had struck home even to the uncultured perception.

I left Agra next morning and started off by a branch line to my destination, finding the travelling very different from that of the first part of the journey on main lines in express trains. Now I was in a narrow stuffy carriage with dust permeating every corner, jolting slowly along through a very dreary, sandy, barren country, but I buoyed myself up with the thought: “I shall be right out in the country among the Indian people and see them as they are—there will be no English but ourselves, and I shall get to know what the life of the people of India really is.”

I reached Hariana at dusk; Bob was at the station to meet me, with an army of puttiwalas who took charge of my seven boxes. The sun had gone down, so the cover or head had been removed from the tonga (double dogcart) in which we were to drive to our quarters.

On the way I was to make acquaintance with the dust, which is a very insistent factor of life in India. It was like thick, dirty-white flour, the roads were overlaid with it, three or four inches deep, and the trees beside the road were white, not green. When people come driving or even walking, their approach is heralded by the cloud of dust they raise as they move along; if a drove of cattle is coming it is a vast cloud.

We had not far to go to the Rest House or Travellers’ Bungalow which was to be my home for some time to come. Throughout India, wherever the official’s duty takes him—be he engineer, revenue-collector, forest-officer, or officer of the police force—there is always a Government Bungalow in which he can take rooms, and a kamsamah (cook-butler) to attend upon him. When Government officials are not using it, other English people may find accommodation there at a fixed charge. The Bungalow housed Bob and myself, but tents had to be pitched in the grounds for Bob’s office and clerks.

The Bungalow rooms were lofty and spacious, the furniture was plain, but all that was necessary was there. In my bedroom I found a dressing-table and glass, an almirah (wardrobe for hanging dresses), a chest of drawers, and a wooden bedstead (on which our own mattresses would be placed) with mosquito poles and net, and on the floor some blue and white striped dhurries (country carpets) were placed. Throughout India one carries one’s own bedding with one. I remember an Indian gentleman told me that what surprised him greatly in Europe was that the hotels supplied bed, sheets, and towels!

In the dining-room there were a large table and some cane-seated chairs, as well as two deck chairs and some cane lounges. The dhurries were red and blue. I was quite pleased with the appearance of the dining-room when the butler had announced dinner.

There were our own lamps with rose-coloured shades, and our own glass, silver, and chinaware, flowers were tastefully arranged in vases on the table, and the dinner was a good one. Indian cooks are very resourceful even in the jungle; with a frying-pan as the only cooking utensil, and two stones for a fireplace, they will produce an appetising dinner.

I give the menu:

Clear Soup.

Salmon Cutlets (tinned).

Roast Mutton.

Stuffed Tomatoes.

Caramel Pudding.

Cheese Toast.

So you see I need not starve out here!

After dinner we sat out on the verandah, which has a pretty flower-garden in front of it, shaded by splendid cork-trees, and on the side of the house were other lofty trees and a golden laburnum, now a mass of splendid colour. The flower-garden melted off into the Pomegranate Grove of which I will tell you tomorrow. I had noticed some stately peacocks strutting about the garden before dinner, and heard from time to time a rush and whir of wings, which meant that they were flying up to settle on the trees for the night, in fact going to roost. But apparently the instinct which warns them of approaching atmospheric disturbance prevented them from sleeping, for as we sat in the verandah, shrill and startling wailing cries broke the stillness from time to time.

“There will be rain,” said Bob. “When the peacocks make that noise it is a sure sign that rain is coming.”

I enjoyed sitting in the verandah chatting, and just remarked, “This is really India,” when, horror of horrors, the loud sound of a gramophone rent the air. I distinguished one of the latest London music-hall songs, one of Harry Lauder’s successes. This was followed by airs from the last “Gaiety” operetta, and so it went on.

Bob told me that the Zemindar, whose house and grounds were close by, had lately returned from a visit to London, and that this gramophone was one of his most cherished acquisitions and that we were likely to hear a good deal of it. On this occasion it played for nearly an hour, and spoiled my first evening in Hariana.

I retired from the verandah to do a little unpacking, and when the gramophone stopped, I was glad to go to bed; and very comfortable and snug I felt with the mosquito-nets tucked in around me, for when the bed is large and the mosquito-poles high, and the nets tucked in tightly around the mattress, they make a little room within a room.

But though I was so snug and comfortable, I, like the peacocks, could not sleep. I was, however, well content to lie still and listen to the various sounds that succeed each other through the night in India.

Night is such a busy time for the winged creatures and the denizens of the jungle. The cicada chant incessantly, the night-owls hoot as they chase their evening meal, the cry of a band of flying foxes is weird, the chorus of bull-frogs, if you are near water in the rainy season, is often quite overwhelming, then in the distance one may hear the call of the jackal, warning the panther, for whom he is stalking, that he scents prey, while on the road, near by, bullock-wagons pass from time to time, and the bells hung around the necks of the team jingle and tinkle pleasantly. In India, travelling and transport work are always done at night when possible, in order to avoid the heat.

As I lay awake listening to these various sounds and signs of a life that was novel to me, I thought how much they were to be preferred to the noises heard as I lay awake (not so long ago) in a private hospital in London. There I used to dread the approach of night. As soon as it grew dark many specimens of foul and miserable humanity began to issue from their lairs in the adjoining slums and made their needs and misery known to the world by a variety of cries. A raucous voice would bellow passionate love-songs, a quavering female voice would follow with a pseudo-religious ditty, then a boy with a painful attempt at jocularity would give a comic music-hall ditty in a squeaking voice, sometimes a broken-down actor declaimed a scene from Shakespeare. Generally their efforts were cut short by the jingle of some coppers on the pavement and an order to move on. How terrible to be reduced to having no other means to keep starvation at bay than by doing something that people will pay you to stop doing; in fact, they will pay you not to do it again.

Finally the nuisance was stopped in that particular square by the matron of the hospital getting a police-inspector to place a man on duty to prevent mendicants frequenting it. Poor creatures! They only changed their beat.

These noises are not all that makes a London night hideous. There is the flare of electric light on the painted girls in the streets, the garish restaurants, the houses where youth and innocence are foully sacrificed, the flaring gin-palaces and their sodden, degraded customers, but there is also the other side of the picture—the open doors of the hospitals—(for it is after the public-houses close for the night and the frequenters are turned into the street, that the greatest number of accident-cases are brought to the hospital); the army of patient, duty-loving nurses, in hospitals, nursing-homes, and private houses, forgetful of self, cheerfully performing disgusting offices, fighting to save life—to save their patients from the consequences of following the lead of the world, the flesh, and the devil.

But I was glad to be away from it all, in fresh surroundings. I fell asleep at last and was quite surprised that morning came so soon, and not prepared for the knock at my door that proclaimed seven o’clock, and the butler’s voice saying: “Char tyar, mem Sahib” (“Tea is ready”). That meant he had placed my tray of tea and toast on a little table at my door and that when he retired I was to open my door and take it in. Indian men-servants, unlike Continental waiters, would never think of entering a lady’s bedroom while she was in it.

Bob was due at his office at eight o’clock and would return for real breakfast at eleven. This breakfast is more like an early lunch. After dressing I put on my sun-topee (helmet) and began to explore my surroundings.

I must tell you about them next week.

Chapter IV

The Pomegranate Grove

I must now describe my surroundings for your benefit. In front of the Bungalow is a garden; in the garden are cornflowers, phloxes, petunias, marigolds, and mignonette, besides small Persian rose-bushes and jasmine. There are also a few bushes of the Cashmere rose, the real original rose, from which all other varieties have descended or been propagated. It is a large, pink, single rose, excessively fragrant.

We are among the Punjaub irrigation colonies, and as I walked down the path I saw a dazzling sight at the end of the flower-garden, a mass of white and pale pink fruit-blossom, which had not been there two days ago, but the water had been turned on, and this was the result. It is said that the drain of irrigation canals has brought the waters of the Jumna so low that boats of any size cannot travel on it and the trade of the Jumna, which was considerable, is almost at an end; on the other hand irrigation means prosperity to the landowners and ryots of the Western Punjaub. To return to my garden. After the blossoming fruit-garden, began the Pomegranate Grove and a thick tangle of dark green small-leaved trees, with flowers of bright, rather bricky-red hue. Most people know the dark crimson of the ripe pomegranate-fruit, but the flower is of quite a different shade. It was a very extensive grove, overshadowed by some lofty shade trees. It struck me as a lovely place wherein to sit and read, write or dream. At present, while the trees are in blossom, it is a quiet place, but later on, when fruit is ripening, it will be very noisy. Empty kerosine-tins with large stones in them will be attached to branches of some of the taller trees, and at the bottom of each such tree will be stationed a small boy whose business it is to pull a rope attached to the tins and make the stones rattle to scare away the marauding birds. Other boys will be there with bows from which they will let out mud pellets, not arrows, at the robbers.

At the end of the grove is a large tank much frequented by water-birds; beyond that rise the walls and flat-roofed houses of the town. It is merely a small Indian country town, no shops where anything required by English people could be procured, but it is the centre of a cotton-growing district, and the great Greek merchants, Messrs. Ralli, have offices here and an agent, who buys up cotton for the Bombay or Calcutta markets. This agent and his clerks are the only European residents. The town is uninteresting, but a little above it are the remains of the old fort, and bathed in the glorious Indian sunshine the general effect is quite picturesque.

The climate here is much colder than in Bombay. Here I am glad of a blanket at night, and a cloth coat and skirt are comfortable wear in the early morning. By ten o’clock the sun will have warmed the atmosphere and diffused a delicious warmth everywhere.

I have now chosen a corner of the pomegranate grove overshadowed by trees, and there I have placed a cane chair and a blue and white dhurrie for a carpet; this will be my own special boudoir, to which I shall retire when I want to have a chat with you on paper, and you can think of me as sitting there to compile my ‘weekly budget.

I sit there so quietly that the birds and animals who inhabit the grove and neighbourhood take no notice of me, but go on with their daily life as if I were not there.

But I am beginning to make friends with some of them. The minors (Indian starlings) are very bold birds, and will come quite close to me to pick up crumbs. They are very handsome, graceful birds and most amusing, chattering incessantly and quarrelling with each other as they patter to and fro looking for food. The little squirrels, whose fur is grey with black stripes, are shyer than the minors, but even they are beginning to look out for crumbs, they will take a run up the trunk of a tree to nibble it, and then scamper back for more. I was amused to see one of them run in between two green parrots who were disputing over some grain, and carry it away while they were chattering. The monkeys who come into the tall trees beyond the grove are endlessly amusing, but I do not make friends with them, indeed they grin and hiss at me in rather a forbidding way, if I pass near a bough on which they are seated. One ventured into the verandah yesterday and the servants drove him off immediately, saying: “Monkeys are very bad people.”

I write a little, and then pause to see what is going on around me, and I often witness a little drama among my dumb neighbours. To-day it was enacted by a monkey and two crows. The monkey was seated on the topmost bough of a casaurina tree, which looked too fragile to support his weight, indeed he swayed backwards and forwards as he was eating a wood-apple.

One crow attacked in front, while the other pecked at his tail behind. He was quite equal to the occasion, and I admired the deftness with which he aimed a blow at the enemy in front, and then wheeled quickly round to give another blow with his paw to the crow attacking him in the rear. The crows retired for a few yards and then returned to the attack; this went on for some time, till they got tired and flew off with discordant cries.

Life in India nowadays seems very tame by comparison with the old times before British rule was firmly established in India. Now no one dare shake the pagoda-tree; then it held endless possibilities for attaining riches and power, and the tales of the exploits and achievements of French and English adventurers in those days, though actual facts, sound like extravagant romances.

Hariana, a district covering an area of three thousand square miles, was the scene of the exploits of George Thomas, known as the “Irish Rajah,” and it was in the old fort here that he made his last stand against the forces of Scindia.

George Thomas arrived in India towards the end of the eighteenth century, as a sailor before the mast, and after a series of marvellous adventures, during which he collected an army of followers, he made his power supreme throughout Hariana, and carved out a kingdom for himself from the ruins of the Moghul Empire. He made the town of Hansi his capital, and there he established a mint to coin the money to pay his troops; he also cast his own artillery, manufactured muskets and powder, making the best preparation he could for carrying on an offensive and defensive war against all comers, knowing that nothing but force of arms could maintain his authority. Thomas aspired to conquer the Punjaub, but the celebrated French General Perron (commander-in-chief of the army of the Mahratta Confederation, of which the Maharajah Scindia of Gwalior was the head), who had seized Delhi and established the Mahratta power throughout Central and part of Northern India, thought that Thomas was getting too powerful and that his progress must be stopped. After vainly endeavouring to get him to join forces, or to enter into a compact limiting the area of his conquests, General Perron declared war on the “Irish Rajah,” sending a force of six thousand Sikhs and sixty guns under the command of the French General Bourguien to invade Hariana.

A fierce warfare was waged. Thomas, who had some English officers with him, drove back the invading force at Georgeghar, sixty miles from Hansi, and then entrenched himself at Georgeghar, holding out for six weeks against the besieging force, which was repeatedly strengthened by reinforcements from Perron’s army. Supplies being exhausted, Thomas’s only chance was to break through the enemy’s lines with his mounted men. He succeeded in doing this one night, but his followers were quickly dispersed by the troops which General Bourguien sent in pursuit. Thomas himself, with four English officers, following a circuitous route for one hundred and twenty miles, finally reached Hansi in safety. There they did their best to hold out, but the French general stormed the town and took it after a gallant defence had been made by the besieged. Thomas and a handful of followers were driven into the Fort, where they were bombarded for ten days, but finally had to capitulate. In these scenes the well-known Anglo-Indian family of Skinner played a prominent part, fighting on the side of Maharajah Scindia’s troops against Thomas. Colonel James Skinner has left a very graphic account of all that took place, in his Memoirs, which were lent to me by his descendant, now living at Hansi.

It is said that the “Irish Rajah” behaved in a most dignified manner at his first meeting with his conqueror, General Bourguien, to whom he gave up his sword; but the General invited him and his officers to a banquet, which degenerated into an orgy. Thomas, trying to drown grief in wine, became intoxicated and lost all prestige. Drink was his besetting weakness; he gave way to it after the collapse of his power, and never retrieved his fortune. After living for a time in obscurity in Benares, he died on his way home to Ireland.5

It is eleven o’clock, so I must break off and go in to breakfast.

Resumed later. — Bob seemed dejected at breakfast and was very silent. I remarked on the crowd of natives collected round his office tent.

“Yes,” he said—“blackguards most of them, and litigation is the joy of their life. It would take the wisdom of Solomon to know when they are speaking the truth. Outside a magistrate’s court, a number of men are always to be found who can be hired for fourpence to swear to anything. To be a false witness is a recognised profession.”

Bob, besides his duties as Assistant Revenue Collector, has magisterial powers, and is obliged to hold Courts of Justice wherever he goes. When breakfast was over, he had only half an hour’s respite, and then was obliged to return to his office tent, where he would be engaged till five o’clock.

So I was to have all the day to myself. Servants always retire to their quarters for food and siesta from twelve o’clock till two, and great quiet reigns in an Englishman’s house at that time. Who can describe the “hush” of noontide in India? Early rising is the order of the day; by noon the morning’s work is over, the chatter and passing to and fro of the servants have ceased; there is no sound but the soft cooing of doves in the barboul-trees, or the creaking of the water-wheel in the distance, and the long-drawn-out cry of the water-drawer urging the patient bullocks to their work as they pace to and from the well—they go forward to drop the buckets into the well, and by retreating pull back the ropes which draw up the buckets, which empty themselves into prepared receptacles. I had not yet got into the habit of taking a noonday siesta, so I took out my phrase-book and began to study the Hindu vocabulary. As I could not speak the language and knew nothing of prices, Bob advised me to leave the housekeeping to the servants for the present—they were experienced men who had been with him some years; but I meant to get the language and fit myself to be mistress of the household as soon as possible. How long I had been poring over the Hindustani alphabet I know not, when suddenly the “boy” rushed into the room and hurriedly began to close every window and door; and other servants were doing the same all over the Bungalow.

“What is the matter?” I asked.

“Kala paous” (“Black rain”), he replied.

Quite suddenly it grew dark, and a cloud of black dust seemed to pervade the air—it permeated through window and door chinks, and covered the furniture and made one choke. We were in the Western Punjaub, and a sand-storm from the adjoining Rajputana Desert was the cause of the darkness and dust. Although it was only two o’clock the servants had to light the lamps, and the atmosphere was that of a London fog. By evening the storm died away, and the air became clear, but the house was in a dreadful state. These unpleasant storms occur not infrequently in this district. I felt glad I had not unpacked the pretty knick-knacks and cushions with which I had intended to make the rooms look homelike.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

A week has passed since I last wrote to you, and as I was out on an expedition into the jungle with Bob, I missed the mail. I am now alone in the Bungalow, for Bob has had to go away for a few days into an outlying district where it was not convenient to take me. Had I gone, it would have meant double tent equipment, etc. Some servants are left to take care of me, and they feel honoured by the charge and will make it their business to see that Mem Sahib is well looked after. Then the Zemindar, who lives near by, called and assured me that I need not feel at all nervous, and asked me to summon him should any difficulties arise. He said: “Both I and my servants would lay down their lives rather than that any harm should befall the lady of our English Sahib. To the English Raj we know we owe all our prosperity. But Mem Sahib need not be nervous, the people in this neighbourhood are all well-disposed.”

I noticed when I went out for an evening stroll with the puttiwala at my heels, that the country people were very respectful. If a farmer was riding along, he would get off his pony and wait till I had passed.

“Unrest” was manifesting itself in other parts of India. Bombs had been thrown; the first killed two ladies at Mozufferpoor, and many people were getting into a state of panic.

I am lucky to have such loyal neighbours.

The Zemindar is rather a remarkable man, an Anglo-Indian who is a descendant of a mixed marriage. An ancestor had done great service to the British Raj, and raised a regiment in Mutiny time, a regiment that is known to fame as “The Yellow Boys,” from the colour of their uniform. As a reward for services, large grants of land were bestowed on him, which had to be divided among a large family at his death.