Isabel Fraser Hunter

The Land of Regrets

A Miss Sahib’s Reminiscences

by “Spero”

To

Lady Ward,

In Affectionate Remembrance of Kindness

Which Has Withstood the Test of Years.

Chapter I

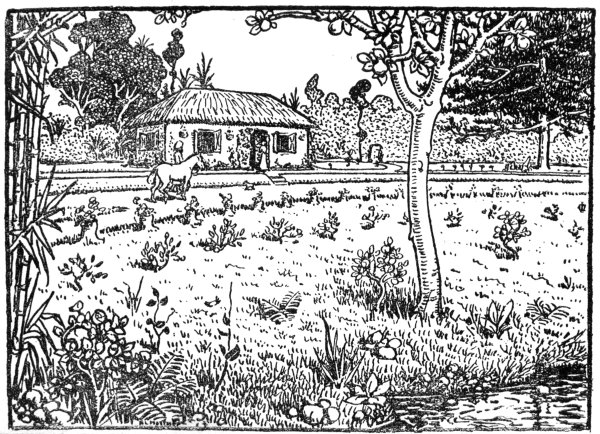

My Cottage

I confess I was overwhelmed with despair as I viewed it—a teeney, weeney cottage. A mere chaumière of bamboo and plaster—battered, broken, frail, and, I had no doubt, unweather-proof. The doors were innocent of locks. They creaked heavily on their rusty hinges; the windows were veiled with cobwebs, and opening inwards, rendered doubtful the beautifying effects of curtain. Oh! dear, what was I to do? They had promised me it should at least be clean, instead of which, packing papers, labels and general confusion, were only a top dressing on the dirt—which was everywhere.

I made a bold stride across the floor—partly to hide my inward chagrin, while I hoped to find better prospects, in what was destined to be my sleeping apartment—scrunch, scrunch, went the floor, and my heels were buried therein. This was nearly the last straw—the last brought the crisis which follows the dregs of despair, when one can despair no more; when one turns the wheel, as it were, and hope appears again.

It was a pitiful wail—a cry, a broken sob, and my poor old ayah, with wizened hands outstretched, proclaimed the verdict of her fellow-servants, “Oh! Miss Sahib, Miss Sahib, humara Miss Sahib turn ne sukta hyara bitoaga, bahut krab hai, bahut mila hai. Miss Sahib bahut jeldi bimar. Hum log sui marjata.”

(“Oh! Miss Sahib, my Miss Sahib. You are not able to stay here. It is very bad. It is very dirty. You will soon be ill. We, your servants, will all die.”)

Her words worked the oracle, my fast failing courage returned. “Oh look,” I said, in my best Hindustani, “see that beautiful orchid, that lovely vauda”—and there through the trellis work of the porch, with its pretty creepers, which had been in a great measure a saving clause, was the lovely spray upon which all eyes had turned. The coolies, sitting outside on their hunkers, were now all alert, as if some great thing had happened. The ayah ceased her wailing, the bearer readjusted his puggaree, the khitmagar, with marked disapproval standing apart, ventured near. So, I was the man at the wheel once more, and with my ungrammatical Hindustani, freely interlarded with English, I made known my wishes and intentions. “All must be spick and span by nightfall,” I ordered. “Set to work with a will, and bucksheesh (the never-failing stimulant) shall be yours.”

It was in a twinkling that they set to work to obey my orders; I would fain have heartened them on with humour, and laughed at the waesome difficulties, but one must never trifle with a native; humour must be a thing apart, else will his energies cease and advantage be taken of good mature. Oh, they are queer kittle-kattle these natives, their depth past finding out, only “like a woman, a dog and a walnut tree, the more you beat them the better they be.” Kindness they do not understand. They will fear that a pice will be taken off their tulab (wage) if one bestows such upon them, or rather if they accept it.

The above doggerel suits the case, but let not the idea take root that castigation is the common lot of the native—the safety valve of the Englishman, and least of all, of a little Miss Sahib, howsoever tempted. You do want to break the law and the prophets, and the native would much rather have a kick or cuff than an angry word, but that kick must come from the Sahib, after which administration of justice the native feels his offence is condoned, forgiven and forgotten; he is reinstated and may sin again as soon as he likes. I shall find it difficult to keep off the subject of the native naukar log (servants): they are so clever, one just wishes them to be quite perfect. Their work is good, but it is the underlying deceit, the lie always so ready to come to the surface, the subtlety, the excuse so tantalizing, the fraud, the open theft, which distracts and disappoints, which, in fact, raises Cain.

It is best to treat them all like children who know no better, but one must never attempt to correct their little failings, for they are proud of their lies, and the innate goodness of the European is not understood by them. The English man or woman is “bahut utcha” (very good) who never cuts them a pice (and I do think that the cutting system from their small wages is a gross injustice), who ignores, or seems to ignore, their petty intrigues, their thefts, their lies, but I can only say that to the mem sahib, who is born to regard these details as part of her very being, there are no offences more irritating. The English statesman will condemn with a high hand the chota sahib (young master) who has just left his mark on his bearer’s back, but let him be sympathetic—the chota sahib had just stretched out for his tobacco pouch, he had only put his last ounce in it a few hours ago, it is empty, and he is miles from the “dukan” (shop); a problem for Labouchere—what would the statesman do?

But revenons, a quick clearance has been made of the odds and ends, yclept furniture of my new residence. It lies, in unpicturesque disorder, in what once had undoubtedly been a very pretty compound. The already over-worn matting is being torn up from its moorings—clouds of dust are blinding the eyes of my now willing band of more hopeful workers; bucksheesh gleamed on the not far-distant horizon. Do not let it be supposed that my immaculate bearer or khitmagar are engaged in this orgie. Oh, no, they stand apart, volubly giving orders which no one heeds. Very soon they will disappear, ostensibly to regulate some work, to make some arrangement—but in reality to smoke their hookahs and chew their vile betel nut.

Meanwhile, let me review the situation. Tell it not in Gath, but my heart rather failed me again, now that the native ceased to clamour out his displeasure at my choice of abode. Briefly, it was Hobson’s choice. In this lovely hill station in which I had elected to sojourn while in the “Land of Regrets,” houses of any sort were at a premium. Small ones to suit the dimensions of a Miss Sahib—an uncommon want in India—all but impossible to obtain. Hence the brave attempt at a contentment which, alas, was only skin deep; but there was that lovely spray of vauda, there was a passion creeper, and, I almost hoped, a gloire. There were ferns galore; some Lenten lilies here and there were trying to force their way through the hard thirsty ground, and, best of all, there was a babbling brook, coursing lengthwise through the compound, almost smothered in undergrowth, yet there, surely there; and there were some fine feathery bamboos and a promise of durantha and—but I must restrain my pen, for the compound was full of hopefulness and hidden treasure, of joy and of profit, too, for here was a pear tree, there a peach, and beyond them a plum or two. Oh, yes, all would be well. There was small credit now in my cheerfulness—but—the inside of the platter must be cleansed first.

India is a land of contradictions. You may wait months and months and months to get a screw put in; but, put on the screw tactfully, well besmeared with bucksheesh, and in one day the work of months can be accomplished by those clever monkey-like artizans. So it happened for me. A white-washer appeared as if by chance on the scene. It is a peculiarity of the native always to know what is going on, and where a rupee can be earned; and doubtless the Miss Sahib’s removal and the state of the cottage was the subject of their table talk that day. Anyhow, very welcome was the white-washer, and quickly set to work; by nightfall the dirty, stained, unsightly walls were all as pure as the drifted snow. Floors were swilled clean by children coolies, who made play of the work and revelled in the pice bestowed with every bucketful of water they brought. The ayah was smiling now, as she made ready a spotless bed for her Miss Sahib.

The khitmagar began to think there were possibilities of space and order for a dinner that night, and the bearer was unpacking bundles and boxes, looking for lamps and the necessaries of life, all surely there, but packed as the native will pack, all safely, but anywhere and anyhow—the knives and forks inside his kummerbund; glasses, pots and pans, cups, saucers, table linen, matches, vegetables, oil and what not, all anyhow but all intact—en passant, my move had been from a very temporary abode, the distance short, and on such occasions one has to submit to the exposure of goods and chattels in any way that the bearers thereof choose to devise. On this point you must not dictate to them.

Chapter II

Philosophy and a Rich Reward

And now to the keepers of pretty English homes let me review the furniture of my little house, which I came to love and revel in, which is full to me of the happiest of reminiscences, and which, with all its drawbacks, I would gladly, oh! so gladly, exchange for my well-appointed English home, its polish and veneer, its trim little maids doing the work of half-a-dozen natives, and its homely ways.

“’Deed Mem, and what’s a finger-bowl?” asked a little sixteen-year old maid fresh from the Board School, in the primitive rooms which were my early choice of necessity on arrival in the homeland, oh! so unhomely that cold winter’s day: and “if ye’re hands are dirty canna ye wash them in the bedroom?” I was silenced, nor could nor dare I expose to her the fact that it was contact with her cutlery which rendered so necessary the use of the “boley glass “ which I missed so much—as much as the arm-chairs which, like the common or garden Englishman, I must now learn to do without, but . . . . my furniture—save the mark—must be reviewed and treated accordingly. It lies topsy-turvy in the blazing sunshine. Nature has done its work of purification, and art must do the rest. I always feel it well to overcome the greater difficulties first—and this makes the lesser ones a pleasure only—so I and my little band of retainers attacked firstly what was intended to serve as a dinner-table. Rough beams had been nailed together with some ideas of precision; some of the seams were gaping slightly, the legs were rather corpulent, ink stains formed a Chinese puzzle on its bare, flat, ugly top, but what matters it!—my snowy damask shall efface them at meal times, and pretty Indian embroideries shall garnish the whole at other times.

I am no artist, but some Aspinall will transform the fat legs apparently into ebony or rosewood. The chairs to surround this at present unfestal board were a difficulty, even to my rose-spectacled eyes. I could fancy they were such as Robbie Burns had in his mind’s eye when he depicted the “Cottar’s Saturday Night.” Their cane seats were gaping, their arms were guiltless of veneer; kuchper-wanee (never mind), a little Aspinall would do the trick, a little fine wire netting could be and was nailed over the deficient cane seats, the brass nails were an ornament, and tidy little cushions of art green, neatly buttoned, were a far greater joy to me than Lazarus’s best could have been—or Maple’s either.

But here comes a welcome interruption. “Tiffin tyari hai, Miss Sahib “ (luncheon is ready, Miss Sahib). Such had been far from my thoughts. I could not hope for lunch in the midst of such confusion, howsoever hopeful it now looked. What, oh! what, had the good bawachi (cook) raised? Where, oh! where was my banquet to be served? My dear little dog, my constant companion, my little love, knew all about it. Barking joyfully, he led the way; no surer guide than he. Under a great spreading fir tree, discreetly chosen, fairly near the kitchen, with the fixed idea of saving himself needless trouble, the khitmagar had laid my table, spread with the daintiness which always characterizes his handiwork. There was enough shade for comfort, yet enough sunshine scintillated through the green branches to tint with rainbow hues the silver and glass; the serviette, folded like a spread-eagle, suited the occasion well, and roses were in a bowl weighted with sand to give it the necessary security.

Could any Royal Highness want more? A plump little moorghi (chicken) which, probably, had pirouetted the compound an hour or so ago in happy ignorance of its fate, reposed on potato chips as a centre dish. Nor were its adjuncts wanting of gravy, bread sauce and hill potatoes of the best, pumpkin, found on the top of the kitchen’s thatched roof, and chupattis, made pancake fashion, supplied the place of bread. There was curry and rice, without which no Indian meal is complete, and there was e-custard pudding—the Indian’s never-failing refuge. Compare this with the spring-cleaning days, with their make-shift meal, in the heart of civilization! And to the credit of the cook, let me add, had he not known full well the simplicity of his Miss Sahib’s tastes, the usual number of courses would not have been conspicuous by their absence, even to the characteristic “irony e-stew.”

A time of unhappiness followed for me. The native must have his siesta. The world may stand still, but sleep he must and will. It is well to follow suit; it allays impatience; so, tranquility reigned for the next hour or two. Each coolie lay to sleep where he had worked, a huge piece of betel nut bulging out of his or her cheek; the babel of tongues ceased, silence was supreme. Even my little companion nestled closer in my skirts, and begged that he also might have his snooze, guarding meanwhile his little Miss Sahib, who, fanned by the great fir branches and lulled by the little babbling brook, no doubt did follow suit.

The day is practically done when the native goes for his afternoon siesta. He returns stupefied with the sleep he really does not need. He is more than replete with “curry bhat” and betel nut; he is disinclined for work. He says, or infers, “kyko ara kam banao, bahut roz hai” (Why do more work, there are many days to come?) To drive him is useless. Better bear the inevitable with equanimity; nevertheless, even for my order-loving nature much equanimity was not required. The order by nightfall, with tea and dinner in bold relief, was all that even my hasty soul desired. Spick and span was my little cottage; quite forgotten, or, a memory only as now, were tukleibs (troubles) of the morning, and very much greater was my appreciation of my little dovecot than if I had found it swept and garnished, and probably, to my mind, unornately ornate.

Why do I love to recount it all? Will anyone like to barter their English home for the rough little structure I have left behind, with its devices and contrivances for comfort, all surely there, prompted by the mother of invention and a part only—therein is the saving clause—of a delightful whole? And now, were I asked to define this saving clause of Indian life or life in India, the that, which makes all uplifting, love inspiring and delightful, I should say—it was the weather, the glorious sunshine, the blue skies, the lovely foliage, flowers and trees, the hills and dales and beautiful scenery, the freedom, the open-air life and, what you must never look for in England, the sociability and amusements, without which Jack must always be a dull boy.

I am speaking of the hills of India, and there is not, I think, one station in the plains which a merciful Providence has not provided with a hill resort within easy reach. I love the plains, too, but (let me whisper it) in the cold weather, when there are lots of gaieties on—balls, dances and dinners; for man and maiden were not made to live alone. Some of the best friendships of my life were the results of chance meetings with my “rights” and “lefts” at dinner. I fear I do not view the mild Indian flirtations, a natural consequence of the life, as mortal sins, but rather the essence, indeed the quintessence, of life, which, let us be honest enough to own, we all like—in moderation. I think with Lady Jephson that “an ideal state of society would be that in which a friendship between men and women, distinct from courtship or love-making, should exist, and,” Lady Jephson continues, “remembering that Caesar’s wife should be above suspicion, it is open to doubt whether the social laws which regulate the intercourse of unmarried people are not too strict with us. Take, for instance, the fact that here a married woman in her teens is given full liberty of action and freedom; she may, in fact, steal her neighbour’s horse, while the unmarried spinster may not even look over the hedge.” Life is prosaic enough, sorrowful enough; its daily details need some brightening effects: therefore, why not enjoy the ball, the dinner, the dance, the festal scene? I flatter myself that intercourse with my fellow-men is good for them, as it is for me; and when, as in India, it was my happy lot to revel with our English lords and ladies of high degree, so unapproachable in this dull, cold, cheerless country, with military celebrities as well and, oh! best of all, Royal Princes and Princesses the Most Gracious—God bless them—then was my cup of happiness quite full.

There was one gracious lord and lady who will ever stand out in bold relief in heart and mind, to my feeble thinking—he, the greatest statesman India has ever known—too great for his surroundings—he was generations before his time. It is India’s loss in these days of unrest and trial that his is not the hand nor his the far-seeing eye to quell the turmoil. He saw the end from the beginning and, who is so clever at unravelling the silken skein as the raveller? Who so quickly attains an end as he who adopted an original mode to set in order the start?

And she, that gentle beautiful lady, that essence of all a woman should be—good—truly good. From my heart’s core I would never cease to render tribute to her memory, for one womanly act, which proved her own lovely and love-full life. She would have given to me what she termed “the second-best happiness,” second best only to hers—“none could equal hers,” she said—and yet, God saw good to gather the beautiful flower to Himself long, long before the allotted span, taking her away from husband and children, from position, wealth, power and all that makes life dear, to the great unseen, the invisible, the unknown.

“Oh! not in cruelty, not in wrath,

The reaper came that day;

’Twas an angel visited the green earth,

And took that flower away.”

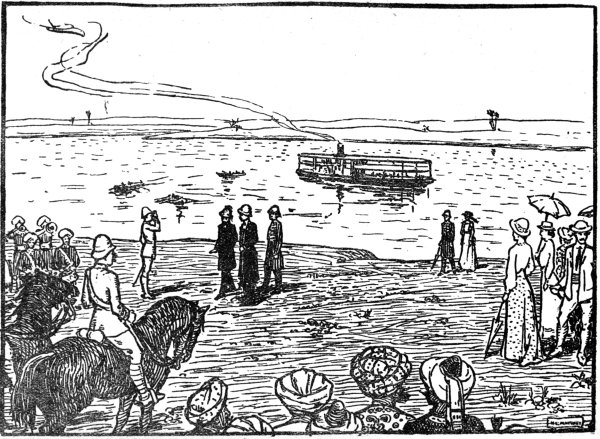

I would fain dwell here on the many incidents connected with her which now illuminate my pen and which make it fly at illegible speed. There was my first view of, and introduction to, the viceregal couple. It was in the plains of Eastern India, under a scorching sun, a cloudless blue sky. Crowds had assembled to welcome the lord and lady. Every honour possible had been prepared for their reception. The station band was playing its best. A fine bodyguard of Volunteers was in attendance, under—en passant—an old Eton boy’s command, a schoolfellow of his own, whom, in spite of the surging years for both, the greater man with pleasing informality recognised and joyfully greeted. The natives in gaudy attire were hustling each other, each anxious to be to the front. There was the great hum of native chatter; but how one always misses the British cheer! There was the little group of English ladies in their pretty frocks, topees and sunshades, all white, so symmetrical and pleasing, a characteristic of the Indian plains, and there was the Viceroy’s flotilla, mid-river, so near and yet so far, for it was at ebb so low that the boats could not reach their moorings at the Ghat (landing stage).

Tiny boats were lowered, and with picturesque effect and dignity unimpaired, the Queen’s proud representative landed, followed by his suite in glittering array. It was a better setting they wanted than rough sand banks and bare shadeless country; yet was ever scene more impressive, more loyal and quaintly grand! was ever the National Anthem played with greater effect? The salute was given and received, the Viceroy inspected the guard, and then the most beautiful woman those shores can ever have seen stepped forward, daintily clad in Assam’s finest silk, a graceful tribute to its people. Some words in the Viceroy’s speech, at the informal luncheon party on the day of his departure, were delightfully pleasing. Asked about affairs American by a bachelor present, who wished to know more than the Viceroy cared to tell, his lordship’s tact and humour saved the situation. “Go you to America and see for yourself: you will find much there to interest, benefit and instruct, and you will find there, too, a good thing, a good thing which I would recommend you to secure. It will not be the best, that I have already deprived America of, but you will find still a good choice.” His Excellency’s speech at the formal banquet, splendid as all his orations were, was political—withal humorous.

In proof of the wonderful powers possessed by their Excellencies in recognising faces (be they ever so plain), I quote the honour bestowed on insignificance, when, over nine months later, at the season’s Drawing Room, my lowliness was formally presented to them. It was in the great crowd of unknown people (for was not this their Excellencies’ first season?) and when the viceregal procession passed through the vast reception rooms from the Throne Room, that the hearty handshake and the kind words of welcome were given to the little unexpectant white-robed figure, who, then and there, blossomed into importance and remark, and who, therefore, from personal experience can vouch for one of the characteristics which endeared this great lord and lady to the people amongst whom they sojourned.

Only a few weeks later and one recalls a scene so widely different, the impressiveness of which can never be effaced. A great congregation, too great even for the cathedral’s expanse, clad in sombrous hue and bowed in genuine grief which did not need the accentuations of Chopin’s music, so expressive of hopeless grief, to aid and abet it—grief for the beloved Queen, who had passed to that bourne from whence no traveller can return. Officials moved about with noiseless footsteps as the bells tolled out their mournful dirge, not one gleam of sunshine penetrated the gloom of sadness: all was consistently dreary, within and without.

It was in an interval of telling silence, all outward sign of office removed, in simple morning dress of black and unattended, that the great statesman, with bowed head, which yet could not rob him of his stately presence, with slow and steady step, took his place as chief mourner for the beloved Queen, the gracious lady whose loss was deplored so deeply. Sad reminiscences must all find place with the glad ones, and soon, was not there the counteracting joy?—merry bells ringing out a proclamation which was satisfaction to everyone, the Indian Empire and the English as well.

Le roi est mort. Vive le roi.

Chapter III

A Midnight Visitor

But I have wandered far from my teeney, weeney cottage, the subject not being nearly exhausted.

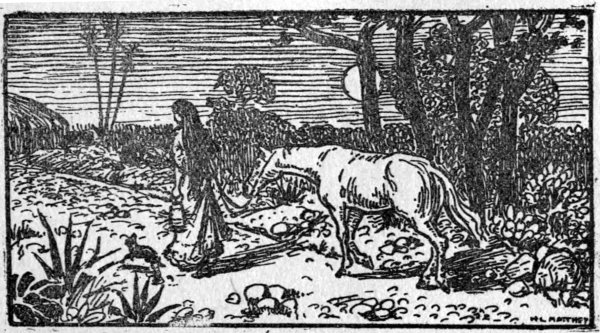

I found it necessary, and a very good plan always, to wear or carry about with me a pair of rose-coloured spectacles. The effect of these was marvellous, and assisted an equanimity of temperament which was good for the wearer, and better still for those surrounding. I needed them muchly on awaking the first morning of residence in my new abode. The curtainless windows, so gaunt and bare, depressed me; the absence of ornamentation chilled my whole being, and these were small details only, for again—the outside view was lovely. A wide range of grand hills in the far distance had a beautiful blue horizon for their boundary line, wide undulating plains intervened, and fresh scented woodland was on every hand. A disturbed night had perhaps much to say to my depressed condition—I had had a midnight visitor—a welcome, yet unwelcome, one.

I was waked by a heavy breathing; a breathing which was persistently sonorous in its determination to rouse me up—two great eyes stared at me in the darkness, a broad flat nose was flattened against the window pane—but it was a low whinny of pleasure that greeted me as I approached. My pony, doubtless not relishing his new abode had come to tell me so. The stables, quite two hundred yards away, must be regained; the track was rough and stony. The night air was damp and chilly, and I . . . . but the stable must be reached, and there would be no gallery to view or applaud. Gently reproving my visitor for his naughtiness, I led the way, stumbling over stones and protruding tree roots, a lantern in one hand, trailing white garments in the other. The scene on arrival was a typical one. The syce soundly asleep on the top of my pony’s grass, shrouded mummywise in odorous clothing, and . . . my pony’s best blanket over all—and poor pony quite nude! It was small wonder he came to tell his tale, and every reason for the syce’s crestfallen and guilty appearance when he came for orders next day.

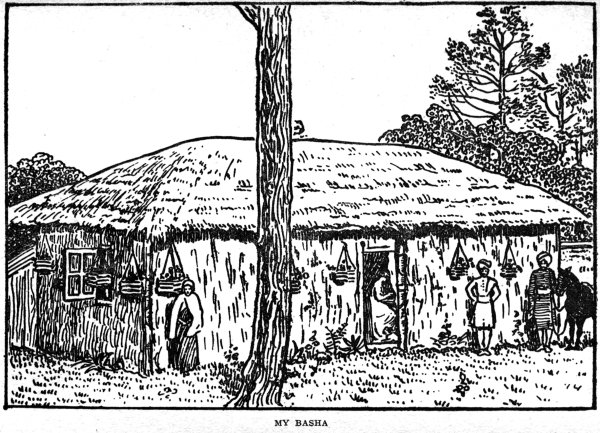

My compound, worthy of a palatial mansion rather than the tiny “basha” (temporary erection) it surrounded, was an inexhaustible source of pleasure. It was, as I have already said, full of possibilities. I resolved I should lay out a kitchen garden. A splendid position on a sunny slope was, after much deliberation, selected by my “malhi” (gardener) and myself. A huge box of Sutton’s seeds was procured, and we set to work with a will—already I scented fresh French lettuce, succulent peas and luscious tomatoes, and mentally invented all sorts of recipes for their use. I encouraged the malhi to work diligently with the choicest Hindustani in my vocabulary. I almost sat me down to watch the various green growths appear.

In due course they came, little green blades, almost one by one; and then, believing they would grow faster unwatched, I resolved to leave my garden alone for some weeks. I felt a grand surprise would then rejoice my heart, and I quite longed for the interval of days to pass. Other eyes than mine had maintained guard meanwhile. It was with angry thuds and threats that I heard the malhi’s voice raised, alas, in futile expostulations. An inroad of cows had consumed the first fruits of our labours, and great ugly hoofs had disfigured the work of weeks and the hopes of months. Alas! we had not thought of fencing in our own preserves: it was useless to lock the door now the steed was stolen. My kitchen garden must be abandoned, and a new link of experience was attached to my chain of events.

My rose-coloured spectacles were in evidence all that day. I contented myself with the knowledge that “biccary wallahs” (native vendors) were galore, and that buying from them would be an amusement daily. I was shortly inundated with them—moorghi wallahs, subji wallahs, all sorts of wallahs. These were at least a joy to my khitmagar, who received from them a generous commission on all I bought, a trick about which I became in course as wise and wary as he. A friend of mine who greatly disliked this Indian custom of being taxed by her servants, offered her cook a wage of fifty Rs. a month, instead of twenty, on condition that he would be quite honest with her. His bargain lasted for a month only. He preferred the custom of his country, and to be left free to rob his employer, and it was Hobson’s choice to agree or be boycotted.

This is a hateful and very common custom in India, and no matter the grade of the employer, the native is master of the situation, and the penalties he can inflict when he is offended or thwarted are beyond description. This is decidedly a difficulty for a Miss Sahib. The fear-inspiring methods of a Sahib are wanted—we will not question what these are. The native is subtle and his ways, as I have already said, are past finding out. I have known Generals and Commissioners, too, come under the lash of his displeasure. It is no use applying to officials for redress. They do not care to interfere. Secure themselves, the difficulties of others less fortunate are a matter of indifference, except in appearance and words only. The dishonesty of the native is a never-failing source of trouble. In this I consider he is greatly assisted by the makers and givers of the law. Rest assured the loser will never recover anything over which the native has shown ignorance of the laws of meum and tuum. One’s only course is to lock the door (if you can) before the steed has been stolen, or maintain stoic silence regarding your injuries. I can speak very feelingly on this subject. It is the one black speck on my reminiscences—the one stain which lightens the regrets.

On one occasion I was deprived of a very much valued possession—my watch, chain and charms. There was no doubt as to the culprit. I cried aloud in my vexation and displeasure. I had not then learnt the virtue which is golden.

“Did you see him take it?” asked the magistrate.

“Certainly not,” I answered; “it would not then be theft.” My claims were dismissed. It was a matter of poor satisfaction to me that high officials, in the years which followed, fell a victim to this same thief, who began, perhaps, his trade with me, and who, had he been flogged for a lamb, would not have been exported for a sheep.

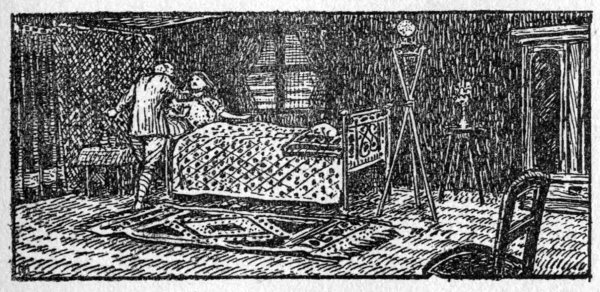

In another experience—I regret to say I had many such—the judge told me privately that he had not a doubt of the guilt of the person I accused; but, he added, the law obliged him to “give the native the benefit of any doubt that remained”; therefore again the culprit went scot free. It is, therefore, small surprise that thieves abound and flourish. On another occasion I appealed to the law to exert its privilege, so far as I was concerned. Again, it was a night visitor—a much less welcome one than my pony. I had been out dining, quite wisely and well. There were sounds of revelry in the stables when I returned, about midnight, but heedless of these, I retired to rest; but, alas, not to dream, for the stable’s gaieties, unlike mine, were carried on neither wisely nor well. These, however, ceased in due course, and the quiet that followed was speedily taken advantage of. Rough indeed was the awakening from the sound sleep that followed. I felt an unusual movement on the counterpane. Believing it to be my little dog, who occupied his usual place on my bed, I gently told him it was not early tea time. Simultaneously with my words and a strong odour of cocoanut oil with which the native always polishes his black body, a shiny hand was laid on my throat, with a grasp which left its mark for some days to come, but yet which did not prevent the indulgence of prolonged screams—a woman’s usual mode of defence. The coward fled with amazing despatch, knocking over screens, lamps, and every article that obstructed his exit. Where! oh where! was my little bodyguard?—sound asleep in his place—and, as I afterwards found, drugged, to leave my assailant a free hand in his onslaught.

This unwelcome visitor was my own syce, who thus sought retaliation for having been reproved for some trifling offence, and who took advantage of the absence of my ayah, through illness, for his midnight raid. The syce was acquitted: such is law in India. While quite certain, mentally, of his identity, uncommon sense alone prevented me risking the assertion on oath in the court of law, if not of justice. My rooms at the time of the attack were shrouded in darkness—the offender had taken the precaution of extinguishing all the semi-lights—and it might be the magistrate would have the perspicacity to follow up my assertions—had I made such—with a reminder of this fact in his conflicting cross-examination. I afterwards proved my suspicions quite correct. The only administration of justice was my own. He was dismissed, his full wage paid him—a large one—because I liked him so well: I was the only sufferer. For weeks afterwards I was boycotted and syceless, and this in addition to having had my larder and stores completely rifled for the dinner party in the stables. which preceded my adventure, and which had rendered senseless the servants who should have come to my aid.

A fortnight later and a similar encounter occurred, this time, however, with practical results, so far as the law was concerned. My orderly had not been dining unwisely: he was on the alert. The burglar was caught, and, I rejoice to say, for once I saw justice administered and for twenty-two months the station rid of the worst thief and blackguard in it. At the same time was the General deprived of his khitmagar (for such was the offender) and, to his annoyance, of his early tea the morning after the event. The next time I saw this Jack of many trades—one of the cleverest servants I had ever known—he was in scarlet livery, and was ministering to the comfort of the guests at a dinner party at Government House, and he it was that I would have hanged long ago for the theft of a lamb—my ewe lamb—instead of which, like the green bay tree, he continued to prosper and grow rich by robbing his employers.

One more such grievance in illustration of the lax laws in India where police administration is concerned, and I hopelessly leave the theme. Years later very extensive were the depredations made on my personal property. With the uselessness of application to the authorities still fresh in my mind, I yet felt the effort must be made, if only to show up the defects in such matters, and in the faint hope that a reform might be effected. In answer to my summons, an officer of justice arrived. He took down all details, and quite agreed with me there was no doubt as to the thief—and there certainly was no room for such—no ability was wanted to make that fact clear. He retired, to return, he said, with the result of his investigations. It was a month before I saw him again, casually encountered on the King’s high road. He had been ill, he said, and he was then going to investigate. I could not find sarcasm to meet the case. He was as useless as he was unornamental, but in my heart I blamed rather the highly paid officials who permitted, and by their own acts justified, such omissions. And yet, in spite of all, I love the “Land of Regrets.”

One case to prove that some ability existed amongst the police must be quoted to qualify my insinuations. A lady, the wife of a military official, had some valuable trinkets stolen from her toilet table through an open window at night. The thief also removed some feminine underwear from a chair close by. The night was chilly: he thought fit to don these. Next day there was a hue and cry for the lost jewellery, the missing clothing was given as a clue. For once the police mastered the situation, with small credit, however, attached to them.

The thief, being a half-witted vagrant, had not mind enough even in daylight to remove the sure means of identification with which he had outwardly adorned himself.

Sir James Outram it was who laid the first fell stroke to the system of “khatpat” (bribery)—pity is that the same influence has not yet permeated the lines of the police. For a few rupees, or even annas, I have often been told, the police allow themselves to be hoodwinked by the offenders, hence follows the better part of silence, however wrong. One avoids the laugh in the sleeve of the policeman, and of being rendered ridiculous in the eyes of the thief.

Chapter IV

A Prelude to Matrimony Made Easy

April’s month, so bright with qualified sunshine, with fresh spring flowers and bright promises, is, to to my thinking, one of the most pleasant in the hills—in this “Land of Regrets.” Old friends then flock up from the plains, newcomers raise hopes and expectations; and life, pleasantly dormant during the cold weather, is all astir again. It is the great time for picnics, before the rains come to make these a doubtful pleasure. The opening one of the season was always to a lovely elevation, some fifteen miles distant, and had for its raison d’être and central attraction a native dance, which took place annually, with a very important object in view. It was a sort of matrimonial fair or a matrimonial auction mart, and the season chosen was a fit and usual time for mating. The native women, gaudily attired in their best, and bedecked with flowers and crude but valuable jewellery, danced in a circle for three days. In their weird shuffling nautch there was yet much method, the difficulty of which has only to be tried to be appreciated. Without appearing to raise a foot from the ground, they heel and toe it, and at the same time glide round, maintaining their circle, rows deep, intact. Around them stand admiring groups of men, each on business intent. They are there to choose wives! Choosing them on grounds as mysterious as do the world at large, with small reference to the little blind boy, who alone should regulate these affairs—and, with as much uncertainty. It did not occur to me that he who drew first drew the best prize in this unique lottery. My choice would rather have gone out to the persevering ones, who nautched the three days of the fête with persevering hope which proved indomitable. Would not such an one better bear the heat and burden of the matrimonial year? An amusing feature of this fête was the anxiety exhibited by some matronly tire-women—anxious mothers no doubt—who drew any dishevelled ones from the ranks of dancers, rearranged, refreshed and reinstated them. This native dance, like many another custom, had probably an interesting origin, but not from the oldest resident, or any authority, could I discover much more than met the eye.

As usual on such occasions, the ride to and fro was far from being the least pleasant part of the affair. It was the pleasant custom of the Burra Mem Sahib1 of the station to chaperone all the girls on her list to this entertainment. Her plans for their enjoyment were most sympathetic. They were not required to ride schoolgirl fashion. A concourse of suitably chosen cavaliers were all hard by at the place of meeting, and thus happily companioned, the large party rode off.

There were some that liked to loiter by the way; others were overruled in their desires by the waywardness of their ponies. Some preferred to go in company, and others chose a solitary mode of conveyance. However, there was pleasure for each and all, and one did not inquire into the unions that resulted from the matrimonial nautch, or the possibilities that followed the rides hither and thither! The ceremonies over these native arrangements are very simple—a little fire, some condiments and a feast: all of such a nature that the laws of God and the Church are not defied should a change of partners in life be found eventually desirable.

A Parsee wedding I attended in a crowded city palace some years later seemed to defy all possibilities of dis-union, so intricate was the ceremony, so innumerable the priests who officiated, that the knot must have been indissolubly tied. It lasted for hours; indeed, I wearied and did not see its finish. What troubled me at its opening ceremony, was the fear that the two couples about to be wedded should get mixed! The expectant grooms and their brides sat on a raised dais. A large white drapery shrouded the brides and another the bridegrooms. Perhaps, had they got intermixed, it would have been a matter of small moment, as these arrangements are all made by the parents who think they know best, and so again the little blind boy is left out of the calculations, and of chief moment is the expenditure involved. This is usually a king’s ransom, and generally exceeds the amount of the latest wedding known to have taken place. I was struck with the significance which probably appertained to all the details of this Parsee nuptial ceremony; the anointing with oil; the offering of the fruits of the earth, and of gold and incense.

A ceremony which preceded these weddings was quite as complicated, called the Investiture of the Silver Cord. It corresponded with our Confirmation Service, but far outvied it in complication. The little Parsee boy of twelve years, who was required to take upon himself all the responsibilities of life and especially those of his caste, was, at the outset, awarded and fortified for it with a magnificent supply of valuable presents. Quite nude at the opening ceremony, the affectionate manner in which his mother dressed him in white clothes of the best, and then presented him for his father’s embrace and the congratulations of his relations, was quite touching. The little fellow looked so pathetic and, like a lamb, ready for sacrifice; and again was there in evidence the underlying significance and the deep reality of his religion to the Parsee.

But again I have wandered from the straight paths, and while the varied seasons in this dear land prompted one to travel all over it, yet the magnet seldom failed to attract and detain one in the pet district of all, while the heat was at its zenith in the plains. For the botanist there was a splendid field for research, orchids existed in grand variety and condition, ferns were of every species, and every flower of the garden flourished apace. It always seemed to me that where green wood abounded, there also was the aviary complete, but ignorance on the subject of birds prompts the wisdom of silence, save to dilate on the sweetness of their notes and their variety.

There was the talkative minah and the “brain fever” bird to tell us summer was nigh, and the cuckoo and the bimeraj which was human in its instincts, and served its possessor, in one case well known to me, as a most useful watch. When a rider approached the bungalow, it whistled “See the conquering hero comes.” When a pedestrian arrived, it chose “The Campbells are coming” to announce the fact, and on the arrival of a carriage, the selection whistled was “Polly put the kettle on.” The talk of the minah is much clearer than that of a parrot, and a favourite always in bachelors’ bungalows, sometimes their greetings are more genuine than polite.

Chapter V

A Tribute to Anglo-Indian Mem Sahibs

I do not think there is anything one misses more in the cold western land called “home” than the sociabilities of the East. What an amount of pleasure the Westlander loses! Surely intercourse with our fellow creatures is a thing to be desired, and how much easier is entertaining really in England, where every means to assist it is at hand, than in mofussil stations abroad. I have heard much in England about the idle and frivolous lives with which our ladies are credited in India, but from personal experience I should like to give an emphatic denial to all such assertions. The wives of officials must entertain, and do so at an expenditure which the entertained often grieve over, as they think of the little ones at home who have need of special care in the absence of the parents abroad.

Who but the Mem Sahib arranges all the details of the numerous dinner parties, “at homes,” and balls which must be given in the season! One, two, or maybe three hundred guests have to be arranged for, and the manner in which this is done proves the lady Sahib is no drone in her hive. It is always done on a scale so lavish and thorough that our home folk might with all assurance take their notebooks and retire wiser women. It is seldom there is a restaurant or confectioner round the corner to assist with supplies! All must be concocted under the Mem Sahib’s order or maybe personal superintendence, and if she is not directing her own hospitalities, she is quite sure to be assisting her friends. Again, decorations at all entertainments are always on an extensive scale—a work in themselves. A few subalterns and young civilians sometimes can be found to assist, but their energies usually depend on circumstances, which the Mem Sahib does her best to circumvent, and generally with success.

One always regrets the trouble involved in general entertaining, and that eating and drinking should be made the central attraction. Is not this animal necessity one of the most unbecoming of operations? Why, therefore, so much publicity? Why not relegate it as much as possible to the home circle? and for general amusement and delectation let there be the pleasant and useful exchange of ideas; and if these do not exist, then substitute games, dancing, music, and such like. I confess to having often found the ubiquitous ball at garden parties very much de trop. One is enjoying a nice talk with one’s best friend, when up comes the hostess—“Do come and play” (always a ball involved), and thus is a quite interesting pleasure disturbed, an affaire de coeur is perhaps interrupted, and a good opportunity is lost, while the good lady goes away delighted with her efforts for her guests and congratulates herself that her party is going with a splendid swing.

In one’s best bibs and tuckers, frisking about is not always undiluted pleasure, howsoever highly to be commended are all health-giving exercises. I have taken part abroad at the liveliest and most frivolous festivities, when the highest (and portliest) in the station have become children again, and thoroughly enjoyed a game of “blow feather” and “bumps,” and when a march round the dinner table of automatical toy figures was a source of endless amusement, and I contrast this most delightfully with the cold make-believe joviality of old England, engrossed in household cares and memories of the past, who, having killed the fatted calf and briskly stirred the plum pudding, quite forget the lighter side of nature—“the merry heart which doeth good like medicine.”

However, don’t let me leave the impression that only amusement is the order of the Mem Sahib’s busy day—far from it. Who so kind as the Anglo-Indian to the sick, who, unfortunately, are always there? No inconvenience is too great to make space for the invalid from the plains, and too much can never be done to assist the patient.

A very heartfelt tribute of gratitude is here rendered to the many whose deeds will never be forgotten. It was in the wilds of Kashmir that climatic illness overtook me. Camping out and touring, and roughing it ever so smoothly, yet was there an unavoidable collapse, a check to energies too keen. It was the wife of the highest medical authority in India who ministered to my needs, night and day, with patience, gentleness and kindness I shall never forget, and added to this were attentions of an equally practical nature from the highest lady in that land, whom I shall ever remember as one of the sweetest and best of women—one it was, indeed, a privilege even to know—and with affection to be ever held in highest remembrance; and these words are a feeble tribute only to the lady Mem Sahibs whose kindness robbed illness of its sting and a lonely traveller of all loneliness.

Chapter VI

A Modern Lisbon

There came a day—a never-to-be-forgotten one—in eastern India when the powers of all were tested and tried—tried, and yet not found lacking; when the inherent goodness of many, formerly seemingly dormant, had scope to shine, and shine brilliantly; when selfishness was a quality unknown, and when sympathy flowed forth in unchecked measure from the more fortunate to the lesser so.

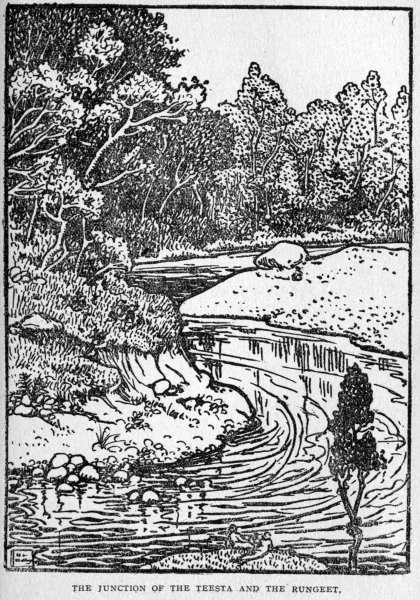

It was a day when the graves gave up their dead, when great mountains swayed to their foundations, and loosening great boulders and rock-bound fetters, sent them also to work havoc and devastation in a relentless fury which could not be gainsaid. Trees were felled down like nine-pins, the mountain sides were lacerated and torn, the streams diverged from their very course or altogether vanished; great yawning fissures everywhere proved how completely the work of destruction had been done, and all in the space of four or five minutes. Houses everywhere were razed to the ground. Lakes were swept away. Scenes formerly of joy and beauty were hideous in their transformation, and beautiful nature was bereft of all its charms.

Dark days followed of sunless cheerlessness, of rain, of mud, and mire, of hunger and thirst, and fatal consequences, of deprivations and discomforts appalling in their effects, and these were whetted with longings for the loved ones far away—powerless to extend sympathy and help. But there was a saving clause—the one thing needful—love, kindness, goodness, which takes the sting out of all earthly woes. These were in unstinted measure given to each and all, and especially to the women and children. It is almost with an apology that I make an allusion at all to the great earthquake of June 12th, 1897, as the tale—written chiefly on a heap of stones, in drenching rain under shelter of a battered umbrella—I then sent abroad; but its horrors can never be forgotten, and there always seems some fresh reminiscence of it still unrecorded; and maybe we still long for the sympathy, a reward of merit so sparsely given by the outside world at the time, owing, however, I am sure, to their defective knowledge of our sufferings.

However, there was a happy side, and it is always best to see it. It is an ill wind indeed that blows no good. No end of love-making and, as I can now vouch, happy marriages followed. Men realized their need for sympathy, and women clung to the reeds, broken or otherwise, upon whose strength it is woman’s privilege to lean. Discussing the why and the wherefore of seismic troubles with a learned Irishman who yet could lower himself to feeble understanding, he summed up the great dispensation in a word: “’Deed, me dear, and it’s just a bad pain in the stomach of the earth, an’ it just can’t help itself.”

Camping out these weird days, surrounded by the ruins of our formerly pretty residences, howsoever joyous at its proper season, had serious drawbacks in the rains. The merest native tents were nevertheless luxurious, after ten days spent in open sheds, which had proved themselves too frail to succumb in the general wreck. I felt in the lap of luxury when a sixty-pound “Patrol” was apportioned for my special use, and a very proud person when, unsought and undreamt of, some weeks later a splendid E.P. was substituted for the former by the kindly thoughtfulness of the Chief Commissioner, who was always a good friend to me.

There was space for high jinks in this, for hide-and-seek in the spacious connaughts, had I been so disposed. These instead were delightfully arranged into wardrobe, dressing room, bathroom, pantry and entrance hall (save the mark), and the whole was pitched by a lovely chestnut tree, with a glorious view of hills in front. I felt there was not even credit due for my overflow of cheerfulness. My little kitchen tent, however discreetly secreted, was rather a blot on the landscape. Smoke and smell were sometimes in evidence—again, ignorance is often bliss where the Indian kitchen is concerned. I have seen rissoles cleverly manipulated by the toes as well as the fingers of the cook, and toast poised for operation on his soles, but—these are details only.

Two of my friends were one day discussing the merits of their cooks, each declaring that his outvied the other’s in cleanliness. “Come to my kitchen and see: no matter that you surprise him at work.” They went—and found the cook washing his feet in the soup tureen! A bachelor friend contemplating matrimony, thought it would be well to investigate the ways of his household in advance. He began, and ended, with the kitchen! He found the cook straining soup through one of his socks! Remonstrated with for such conduct, the cook was equal to the occasion. “Pardon me, Sahib,” he said, “but it is only a dirty sock! See, the dhobie man waiting to take away master’s wash.”

Being in cantonments under military care (and surveillance) was another flower in my garden, and adjacent to the camp of one of the best and noblest of the “servants of the Queen,” I was happily content with the arrangements which Government in its capacity of general housekeeper had made for my comfort, who was not officially entitled to any care.

Searching in the ruins for buried treasure was one of the day’s lighter occupations. Can I truthfully record the fact that I stood by smiling while my best frocks were drawn out of what can best be described as a mud bath, with great stones intersected therein, lacerating their folds into ribbons in their extraction! Some muslin frocks were quite grotesque; riding boots, bulged out with grit and mire, presented most dissipated attitudes; hats were quite past a joke even. Silver things, which could not really disappear, were altogether non-existent for me (I was not the first to search my own ruins).

A most pitiful sight was the butler’s pantry; a very bloodthirsty battle might have taken place there. A large quantity of very excellent bramble jam had consummated its existence the very morning of this momentous day of upheaval, the large glass bottles in which encased must have charged each other again and again with force and fury irrepressible to have attained such results. Great crimson stains were everywhere, and these, lashed for days by a cataclysm of pelting rain, were productive of rivers and pools of that which verifies my descriptive statement. Stranger than fiction, too, were the happenings: a cut-glass salad bowl was found, wedged in the branches of a friendly tree, and quite intact, and this is but an instance.

It was by the irony of fate that, in this harum scarum scatter, articles, chiefly of attire, which one usually relegates to one’s dressing room except on Dhobie days, had so often possessed themselves of conspicuous outside places—fronts seats, in fact. Oh, yes, I smiled, and smiled broadly, I and my good Gurkha friend, to whom I entirely attributed my equanimity, a small reward to him for attentions too sincerely kind ever to be forgotten. We rejoiced over the finding of one great overland box securely fastened. What joy! I should have “frillies,” I felt, enough and to spare. The ayah and the bearer were jubilant. They had secured all they could, they said, and all were intact inside. There came a day—not far distant—when this box came to be dissected, the day the ayah and the bearer had claimed leave to go to their country. Found therein were only broken bottles, papers, rubbish, and then and there for ever was shattered all faith and trust in the sons and daughters of the soil.

These ruins which I viewed with so much borrowed equanimity, the reflection of the kindly support given to me in my time of need by my stalwart Gurkha benefactor, were the remains of a goodly stone-built edifice, one which I called “home,” and which, after three months of hard labour, decorating and remodelling, I had only that morning pronounced very, very good: but man proposes, only—

I went for consolation and counteraction of my own pains to the funereal pile of a friend’s ruins. She, too, was smiling. She was the station’s best girl, recently married, and was having search made in the ruins of her house for her much-prized wedding gifts. A Burmese bowl was brought out flat as an opera hat, and a wedding gown, recently so beautiful, was now a dripping mass of slime and lime, laid aside to dry in the sunshine and then be passed on to swell the bonfire-heap of rubbish. “I cannot grieve for anything,” she said, “but for my poor little ayah buried in the downfall.”

Were one free to dilate on the experiences of others during that momentous time, it is not a chapter, but volumes, that could be written; and at this evaporation of time, it is the seamy side which appeals so strongly to me. Four gentlemen were dining in what had formerly been their hen-house, the thatched roof, never of the best architecture and slightly the worse for the turmoil through which it had passed, with small premonition, gave way, and landed hatwise on top of the diners. The station’s version of the episode next day was that each head perforated the thatch as it fell, and thus decorated, the owners paraded the compound until released from bondage. This, by the way, should be taken with the proverbial grain of salt, and is only one of the many little fictions which were circulated for the general amusement of people who were sorely in need of some antidote for their sufferings and deprivations.

My “George Washington” pen continues the reliable narrative. This hen-house was, necessarily, also the sleeping quarters of some, if not all the occupants of what had formerly been a most delightfully hospitable chummery. Owing to its decapitation, ingenuity was taxed to the utmost to find other shelter for the night. The ground was quite impossible, only one alternative presented itself. Splendidly thick trees with spreading branches were in evidence all round, so sheets were procured, and these, hammock-wise arranged and suspended ’neath the branches, formed an example which found imitators in these sorely strained days, and at the same time supplied fresh “copy” for the station’s “charivari.” There was also a humorous aspect to the General’s residence, a tiny rickshaw house, which, in its frailty, had defied the ’quake by quaking with it, and quite grand, because it was spacious, was the dilapidated coach house, in which a popular official not only lived for many weeks, but dispensed, as was his never-failing custom, hospitalities, and with the clever contrivance of his wife, sheltered others as well within its cracked and battered confines.

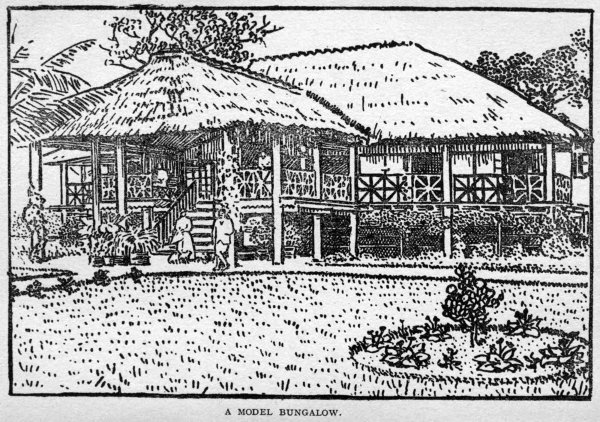

The little thatched huts, which sprung up in the station to replace tents for the cold weather, and in anticipation of more secure tenements for the future, were picturesque, if not palatial. They were an index of the ability and capability of the occupants as much, necessarily, with a limited labour supply, was left to them by the constructors thereof. Quite wonderful was the comfort and order which could prevail, and, alas! very pitiable could be the results when talent and taste were not exercised or available.

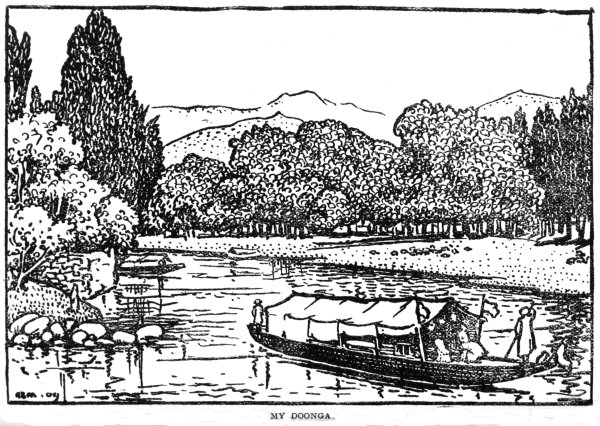

The little basha hut by the wayside in cantonments, kindly, most kindly granted by both General and Chief Commissioner to the little Miss Sahib, who was not entitled officially to any roof at all, was, in proof of her gratitude, as ornate as hands could make it, inside as well as outside. My picture, taken from a photograph, is therefore a true delineation. For two years, with fleeting visits elsewhere, was “Home” its proud title; and when the fiat went forth that it must be relinquished for reasons of security, the “teeney, weeney cottage of bamboo and plaster, battered and broken, frail and, I had no doubt, quite unweatherproof,” was for a long time felt to be a poor exchange. Added to the original photograph, as detailed in my earlier pages, is a ghostly figure escaping from the bathroom, escaping from the burglar’s grip and fleeing for protection to the nearest friend, clad only in robe-de-nuit, shoeless and defiant of the cold December’s midnight, heedless too of rough and stony paths, quite fearless, only troubled because of the absence of the little bodyguard who could have failed only through necessity. Who, with all these adventures, experiences and good things, could have aught but regrets for the dear adopted land?

One more experience only and I must restrain my pen. With the erection of huts, came dinner parties galore, withal for a limited number only, as space necessitated. They were, however, for that reason the more numerous. The rains were still with us. It was not uncommon (as in the days of Lord Auckland in Simla, and long before the beautifully secure Viceregal residence there now) have recourse to umbrellas during dinner! That, however, was a small detail when compared with the difficulty of transit to and fro, owing, in addition to the rain, to the quagmiry state of the roads and paths, which naturally could not receive primary attention, if any at all, at such a season.

One of the many invitations with which I was favoured, which partook somewhat of the nature of a command, must at all perils be obeyed, and gladly so. I hoped the night would be fine overhead, I needed not to hope for such underfoot. The fates were unpropitious. It was with unrelentless fury that the storm clouds expended themselves in torrents. I anticipated the worst when my rickshaw men, enveloped in sacking, came to tell me that they could not possibly take me out. Oh! the wretches!—with their bare legs, what mattered quagmire, be it ever so miry? I adopted a quiet commanding tone of persuasion, but of no avail. Next I threatened, and lastly—strongest hope of all—promised unlimited reward.

The oracle worked. We started—slush, slush—up to the axles in the mire. Very quietly I added all the words of encouragement I could. That we reached our destination at all was matter of deepest congratulation. I did not give a thought to the return journey. Well that I did not fetter mind or manners, for it was in vain that the Miss Sahib’s rickshaw was called for. The rickshaw was there, where were my flat-footed animals? Nowhere to be found! I could not confess my humiliation to the fine scarlet-liveried retainers who surrounded me! They would not understand insubordination, and would only attribute a failure of virtue in the Miss Sahib. She was quite sure to be the offender, nor credited with having shown every consideration possible. The distance was not great, I smilingly vouchsafed, while appalling visions of the miry, sloppy route—path it could not be called—as it neared my dwelling, rose mentally before me. I gathered my skirts to their highest. I did even more, for the night was fairly dark.

That I arrived home bodily intact is now proved, but without my shoes, which were found after many days feet deep in the slime. I was mud and mire from top to toe. Did I kill the rickshaw men next day? Oh no! Not one word of my discomfiture was ever divulged to them. That would have been for them satisfaction too great. Smilingly, rather, they came for their reward next day and got it. There was also a reward for me, and a silver lining to my cloud. A fine way was laid to my chateau, and a fresh proof was given too, of the goodness and kindness of the best of Chief Commissioners.

Chapter VII

Life in the Plains

The exigencies of fate and the solicitations of anxious-minded relations obliged me to relinquish, but not without regret, the ruined citadel for a time. One felt guilty of cowardice, like a captain deserting his ship, or a soldier his fort. The interest of watching resuscitation was not the only regret. There was still scope for untrammelled usefulness and sunlit cords of sapphire blue, held by the little blind boy, were hard to stretch, even for a time.

The usual mode of conveyance from hill stations in India is so fast being superseded by motor power that I would hope to immortalize the good old way by describing it in my pages. Imagine a little springless cart, with deep set floor, to reach which a high step was involved, or by tipping the barrier a head-first entrance could be effected. This appertained to the front seat only. For the back, a flying leap was required, a one, two, three-and-away stimulant, or much hoisting on the part of assistants. This Royal Mail or Government conveyance—and it was no respecter of persons, the same for the highest or the lowest—had for covering an arched canvas roof, or hood; I say roof advisedly, because it was always there unless removed by the caprice of accident. Two straight bamboo shafts attached lengthwise outside the body of this cart confined one pony, or tried to do so; a second pony ran attached alongside, outside the left shaft. A problem I never succeeded in solving was which did the work, or which did most, or least, or was it fairly divided?

The harness for this unique vehicle baffles my descriptive powers. There was some leather about it; there was much rope. Where there was strapping there were usually many string-made repairs, for which I noticed the driver always kept a large supply in a bulging-out pocket, and there was a cross bar of wood or bamboo cunningly placed to keep the outside pony in subjection, if not in order.

Of the ponies it is hard to speak, they were usually the pick of “badmashes” (villains), all too unruly for other service. They jibbed, they reared, they kicked, they bolted, they did all those things they ought not to do, and, only under severe castigation, what they ought to do. I have had the misfortune of being inside when a fire had to be lit ’neath pony’s “tum-tum” before he would advance an inch. To blindfold him in order to place him in the tonga at all was a common occurrence. I have often begged for his deliverance. Only on one occasion was I listened to. The waywardness of the pony must be checked, they said; like the little boys and girls in the nursery, they must be shown early they were not to have their own way: the way must be made hard and unpleasant for them. Later on in the children’s lives, while every effort had been made in infancy to check ardour and ambition, they would be applauded for persistently persevering in having their own way, and how many a life is spoilt by needless control and interference! If the ponies were ever thwarted in their desire to return to their wayside stables, sometimes they attempted suicide over the khud in preference to submission. This was decidedly inconvenient for peaceful passengers not bent on self-destruction. Fortunately such efforts were of rare occurrence, and mishaps, to the credit of the management be it said, were rare.

The hard wood benches inside this char-a-banc were cushioned with pine needles, therefore they were none too soft. Passengers usually tried to supplement these with downy arrangements, but with doubtful results, as these always had the fatality of slipping and of being anywhere but where required.

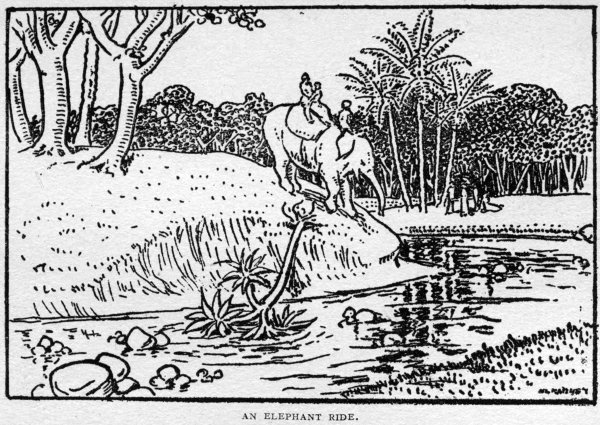

I chose usually a less exciting but much more delightful method of reaching the plains. I preferred riding, picnicing and camping by the way, enjoying at my leisure, instead of under panoramic bolts and jars, scenery the most beautiful. There was no fear of solitude, beautiful nature belied the term; it was always weaving beautiful romances for me. Once, only once, were my pleasures divided and an escort deemed advisable. That was thoroughly nice because of its delightful character, but was not guard against an inroad of native dogs on the supply of cakes with which our stores were flanked and fortified for the campaign.

Leaving quite cold weather behind, it is almost summer weather that one returns to in the plains. White frocks must be refurbished and punkahs are usually in evidence, at least in the lower plains, for the hottest part of the day. The ceaseless variety of place and people in India is ever source of greatest interest. Life in the plains is widely different to that in the hills. The latter have English climate, only far better, with their own delightful manners and customs far in advance of England’s. Take, for instance, the early rising habit, to which I have no doubt England will soon with wisdom succumb. What is more delightful, more useful and beneficial, than the freshness of the early hours—say from five to seven in the plains of India, and six to eight in the hills? England’s are quite equal to those last in benefit, and yet all the world is asleep, at least all who have any choice, and these prefer the night’s extension of energies in artificially-lighted rooms, with deterrent effects on health and longevity. Once try those early hours, and a recurrence to the present custom is more than improbable. Experience of Anglo-Indians in England is proof of this.

I know well now an old lady in England who can speak of the Lucknow horrors from personal experience, and yet at five o’clock every morning is astir, busy with her correspondence and her various interests, while the younger members of her household, and, of course, her servants, are still asleep. I have called my friend old, and uniting her with the mutiny speaks of the heat and burden of the day being past, but to the credit of life in India be it spoken, she is not old in heart, mind, or form. One tale she told me of Lucknow, not, I think, recorded elsewhere, which is pathetic because of telling so nearly home. Her father was the brave general, the gallant gentleman who, without casualty of the most trifling kind, led his troops into the Residency from Mutchli Bawn. Long and prolonged were the enthusiastic cheers which greeted their entrance and success, but while still uplifted with the outburst, the approach of an aide to tell him that his pet daughter, sheltered with her two children in the Residency crypt, had by a cannon’s ball been shot through both limbs and had instantly succumbed, turned the fleeting gladness into sadness.

Chapter VIII

The Simple Life

I love the plains in the cold weather, and residence there, such as was my good fortune, was of the best. The bungalows, either chung or on the flat, can be equally salubrious. I would give a preference to the former because, being poised six or seven feet above the level, ventilation is more free, and, indeed, one can there live in a hurricane, with doors and windows all open, as is the custom, night and day. What a delightful contrast this is to the homeland with its multifarious bolts and bars, and a tribute too, is it not, to the native. True, a nightwatchman is on guard and supposed to keep patrol, but the best bench he can find is his choice when circumstances permit. I have vivid recollections now of the result. Yards and yards of snoring, so long and so continuous that there scarcely seemed an insertion of breathing space, and thus was the night air rent. A visitation of jackals sometimes disturbed his slumbers, but even then he was first aroused by the dogs, the best watch of all, with scent so keen.

The early awaking is delightful in the plains. Perfect stillness reigns. No traffic of carts or motors or discordant street cries destroy its peacefulness. The air, weighted with dewy freshness and scented with roses, mignonette and violets, is wafted to the presence with every breeze. It is as fresh as a leveret or as a little rested child that one stretches out arms to greet.

The great gong clanks out five of the clock, and native life is again astir for its full, yet simple and restful day. There is no hurrying to and fro; no scurrying and scuttering: all is easy, leisurely tranquility there. My picture is of a model bungalow surrounded by acres and acres of neat symmetrical tea garden. The bungalow is verily an oasis in its midst, with tennis and croquet lawns all taut and trim. The hot sun beating on the fernery’s primitively thatched roof, scintillates thro’ it, and produces the steamy atmosphere necessary for its well-being. A peep inside reveals a magnificent display of exotics, and confirms the opinion of the climate’s wonderful powers. With the sun all but at its zenith, a lovely cool breeze qualifies it, for it comes from the great snowy range of the Himalayan mountain tops, so far away, yet seemingly so near.

The air is redolent with the highly-scented trees and shrubs peculiar to the East. The great cocoanut tree is overweighted with its offspring, the plantain secretes ’neath its protective branches great bunches of golden fruit. The passion creeper is fast approaching its full glory, and roses and orchids are everywhere. In further proof of the powers of the plains, let me lead my readers still further afield, and there lies a trim kitchen garden. A great well in its midst, which would have been a wealthy dower to the daughters of Israel, provides water for all, and accounts for the prolific and varied produce within its confines. There are rosy tomatoes and peas galore. There are cauliflowers and French beans enough and to spare, common culinary necessities abound, and lettuces, which might be a joy to Covent Garden; and I see the gardener now hauling great bunches of artichokes from their lair, and I am content and already anticipate a menu with Palestino for its opening event.

A winding pathway, discreetly shaded, shields from the common gaze a little model miniature home farm. The odour which greets the visitor is milky. A contingent of fine fat cows are being groomed; even to the spraying of their mouths, no detail of toilet is omitted. The American system of milking by electricity has not yet penetrated to these wilds, but you may rest assured that all is clean in this farmyard, and that the Mem Sahib herself sees the milkman (no rosy dairymaids here) wash and scrub his hands until only the natural black remains. Two or three fleecy sheep with bleating baa lambs, their toilets also superintended, are happily crunching their daily doles of oil cake. Pigeons are fluttering about, and descend in swoops to steal from the various contingents getting their chota haziri.2 Cocks and hens, struggling for their rights, are everywhere; the latter are quite in the majority. Polygamy is very much the order of the day, and, like a veritable lord of creation, Master Cock struts about followed by his harem, whom he tries to protect from the envy and admiration of his fellows.

These, let loose for their morning stroll, take full advantage of their freedom, and are only safeguarded from trespassing on the garden preserves by a company of English terriers whose office it is to say them nay. Loud only is the Mem Sahib’s voice in expostulation, when the pet Brahmins insist in their ambitious ventures to test the early seedlings. A tussle for supremacy follows. Fatal sometimes is the result. A jury is summoned, and death from misadventure and over-zeal is the verdict, and a dainty morsel is provided for the sweeper’s dinner. A rider is added to the effect that Tiny and Tootles must be placed under arrest for some days to come, until they have learnt the Early Breakfast. limit of their prerogative. I maintain a discreet silence when the sentence is pronounced, for I greatly fear me that the dear little villain, crouching by my side with an assumed appearance of ignorance and innocence of the morning’s fray, had in reality much to say in aiding and abetting the ringleaders of the kennel. I have no doubt he was in at the death, but so complete is the understanding between us that my “fie-fie” finger raised in reproof is all sufficient. Lover never raised to his lady eyes more beseeching or more tender and true, than did my little four-footed friend to mine; and with return which the most devout might simulate . . . and envy.

Further afield is a group of more special interest. Removed from the common herd of everyday cattle are the ponies. There they stand haltered each to his own special post under the shade of great spreading chestnut trees, spick and span as elbow-grease can make them. We do not give the generic term of “stable” to our ponies in India. They are our friends, and have each a special place and distinctive name. Always termed “ponies,” too, they may be rising 14 hands and more; the smaller, 12 and 13 hand polo ponies, are less in evidence nowadays, as the regulation 14 hands is now a recognised necessity, save, perhaps, in Manipur, where the little sturdy hill ponies are still found good enough and certainly safer for the game. In the midst of this group of ponies, so happily sheltered, is a dear little brown pony. His lesser dimensions are no gauge to his appetite; it quite equals that of his more stalwart confrères. He is usually first at the feeding trough and quite the last to leave it, for he always has a look round for the crumbs that, perchance, may have fallen; nor is he last in the procession returning from the morning roll, for after completing his work of scavenger, by some “gainer” route, he will regain his place at tail end if not of middle man.

“I see the long procession,

Still passing to and fro,

The young heart hot and restless,

The old subdued and slow.”

Micawber leads the contingent because of his seniority. He has seen better days, but still is his white coat glossy, tho’ somewhat “hilly” are the hind-quarters it covers. Maori feels quite equal to holding her Australian head erect; she is less proud of her tail which, in spite of daily applications of Harlene, does not flourish apace. Taffy Waler is quite sure of his superiority; his is the “young heart hot and restless,” but whose good breeding enables him to suit his paces to the needs of the moment. Then there is poor pensioner Pickwick, who has born the burden and heat of many a day, who with care and tenderness is yet spared to enjoy the “old age” pension which he has as richly earned as any of the subjects who thronged the home offices for theirs on the 1st January, 1909. Caesar, the little greedy brown boy, who yet finds internal space for the largest dessert of sugar cane, is chiefly conspicuous for his magnificent tail and mane, and the love his mistress bore him blinded her to all other defects. Alas! only that tail and the hoofs now remain, with memories of his oft-repeated devotional attitudes and many escapades. A lamentable accident, the result of his enervated old age, reduced his days of pension, and howsoever kindly assisted, may we hope with the spiritualists, to a better world, there were yet salt tears to furrow the cheeks of his devoted mistress when the crisis, tho’ ever so gently broken to her, came.

My illustration completes my pen picture. A wounded soldier, obliged to lay aside his accoutrements for a time, rests on the verandah. A less pretentious one, an honorary one, is supposed to be in attendance on the invalid. Another, mine host, seems to be “blessing the Duke of Argyle,” and the Mem Sahib is again in evidence.

Chapter IX

Mofussil Gaieties

Life in the mofussil plains of India, in the cold weather, which is the season, is of a most lively description. In a state of chrysalis all the hot weather, all have resuscitated and are on the alert to enjoy their brief time of respite of about three months only. Camp meets, race meets, gymkhanas and all sorts of contrivances to get pleasure, are the order of the day, and everyone is full of energy to contribute their best efforts in detail to the general success of the whole.

People troop down from the hills. Every bungalow is stretched to its utmost limit, and from all the outlying districts lonely sequestered outcasts come to the more central stations to make merry once a year in the general fray. From station to station do they go, and are only partly satiated when the last gaiety has come. Race meets are the great attraction, when the frivolling days only end to begin again. The candle is burnt at both ends. The races usually take place in the morning. Tournaments fill up the day hours, and yet is there energy left for the balls, dinners, cinderellas, theatricals and concerts which occupy the night hours. Well, these come but once a year, and the good cheer must be appropriated by each and all.