Life and Loves of a Prodigal Daughter

Being the Intimate Memoirs of Gervée Baronte

Author’s Preface

As my mind goes back over the past my life seems to have contained in experience and events enough for twenty lives. How did I ever live it all? I ask myself. Had I known I was to live it, would my courage have been sufficient to face it?

There was never a dull moment. It has been crowded, packed to the brim with excitement, misery, work, luxury and poverty. Circumstances have often demanded the last ounce of my strength; but something has reinforced me at the breaking point and driven me on. Reeling through incidents as if suffering from an attack of vertigo, I have stumbled on—events flying past like scenes from an express train. How they have flashed past—the struggles—the difficulties—the unfair opposition—the accusations—the escapes—the adventures in love and passion—the few scarlet triumphs! The giddiness of it all makes my brain reel—my alarming, impetuous brain; for ever fighting a losing battle with what tranquillity it can muster. The days have not been long enough to accomplish what had to be done. Insomnia has been a good friend, for it has given me the time and the peace to think.

You begin to doubt because the story is so overwhelming—the activity so mad—the longing so intense—the energy so extreme.

I am the grave in which all this is buried. It was buried deeply and over it I placed the stone of secrecy. I meant never to remove the stone, but others have threatened to remove it, and with their clumsy, unsympathetic hands to exhume the contents of the grave.

I prefer to conduct the excavation. I shall put everything before you and you shall judge. I cannot hesitate in the operation to show you the many sides of each experience for one presses down on the other and there are so many to unearth.

G. B.

Chapter I

I shall not begin by telling you about my family. Too many autobiographies begin with grandfather and grandmother, who, after more than one hundred and fifty pages, make room for father and mother and Uncle John. Somewhere, after the family has had its rather dull say, the person who is writing his story emerges from this welter of family bickerings and frail exposures as if he were apologizing for entering the sacred assembly.

My birth would not interest you. Birth is always the same whether it occurs in a palace or a hovel. Mine occurred in a middle-class home in England, quite by accident, and from the impatience to get things done which has never, at any moment of my life, deserted me. Mother was on her way to Rome to join my father. She had been for a few months with her family in Egypt and had broken her journey in England to visit one of her school friends. If I had waited I should have been born in the eternal city of the Duce. My birth made no difference to anyone however but the unfortunate lady whose home I had disturbed by my impatience.

One of my earliest recollections is of a vegetable shop in Rome where my nurse used to leave me standing for hours while she gazed into the eyes of her Giuseppe, as he, little heeding his customers, weighed out potatoes and onions and wrapped La Stampa round celery and fennel. I wandered round the shop nibbling at carrots and chestnuts. I bit into apples and tomatoes and turned the bitten sides down. I have often wondered since what the people thought who bought the bitten fruits and vegetables; for Giuseppe was too interested in the glowing face of his Ida to notice what he was weighing out. I think berries attracted me more than anything in the shop. I delighted in squeezing them between my fingers and watching the juice run down my hands. On days when blackberries and raspberries were temptingly offered for sale I was very thoroughly dyed by the time Ida could tear herself away from her sweetheart. I question now if Giuseppe occupied this tender position, for the barber, to whom she took me to have me cleaned up before we went home, held her hand as long and as thoroughly.

We always reached home quite breathlessly and my mother was told of the passeggiare lungo lungo. I think my mother believed (if she cared at all) the lie about the long walk. I knew Ida was lying to my mother, but I never gave the show away. Even as a little child I realized that many things were spoiled by too much talking. Then, too, I enjoyed the visits to the greengrocer and the barber. No doubt they were more amusing than being dragged through the streets by Ida’s hand. Occasionally I went to the Gardens and played with other children. I remember wettings under fountains and leanings over the marble edge of the basin to catch gold fish.

Sometimes my father took me out. He would buy me everything I asked for. I loved him as a child loves a popular hero or some great person of its dreams. Perhaps I loved him more because I saw him seldom. He did not come home for weeks on end; and when he did my mother would sit quietly crying. Sometimes she refused to speak to him, then he would give me all his attention. He threw me up in the air and caught me, played little tunes on the piano while I shuffled about the room trying clumsily to dance. Once he took me to visit a beautiful dark-eyed lady. The lady made a great fuss of me, giving me everything in the house to play with. Father was very proud of me, calling attention to all my little sayings and doings. Later he introduced me to certain of his mistresses as his little sister—but I was thirteen then, and father never got beyond his youth. As a matter of fact he was under forty when a motor-car dashed over the edge of a cliff instantly carrying him and his friends into eternity. It was a fitting death for him, for old age or disfiguring illness would have driven him mad.

My mother never understood my dashing, irresponsible father. If she had known him a little better she would not have taken me, when I was four years old, and hurried home to her parents. Mother closed her eyes when she should have opened them, and opened them when she should have closed them. Jealousy and bitterness blinded her to my father’s better qualities. She was a cold, dispassionate woman given to self-pity, considering only, what she called, “morals” important. She never understood emotions. She knew nothing of the necessity of putting new earth about your roots when you drooped and wilted. I do not wish to mislead you into believing that I did not love her. I did. I understood her more and more as the years passed. She was exact and steady. Her mind attacked everything with geometrical precision. What she knew she knew. No one could shake her belief in anything. I never knew her to he or exaggerate. She never gossiped or indulged in slander. She had a great character, but she was the woman to save a village and lose an empire. Always she remained an outsider in her immediate family.

Her father was the most lovable man who ever lived in spite of his violent intelligence which had to probe into everything. Her mother had a whimsical sense of humour which delighted everyone who knew her. Her sister—she had but one sister and no brothers—had all the warmth she lacked. My Aunt Vera was one of my dearest companions. I could tell her anything and be understood. She had none of mother’s cold chiselled beauty which occurred to you rather than startled you, but she had colouring and brilliance which were much more fascinating.

The torch which started the Roman conflagration, from which we escaped in such haste, was a letter which mother received from one of father’s kind friends telling her of certain jewels (jewels have always been the curse of my life) which father had given his then innamorata. I can still see mother standing under the light with the letter in her hand setting her face into that rigid line which meant determination to carry something through. Perhaps she ground her teeth, but she didn’t cry. She cried only when father was at home. I think she did it to shame him.

Ida put me to bed while mother was reading and re-reading the letter. The servants must have worked very fast that night for in the morning everything was ready for our departure. I was told that we were going to visit grandfather and grandmother who, shortly before we left Rome, had “taken” a house in Furness, near Barrow. I was to learn that grandfather was for ever “taking” houses and leaving them. Some he bought and some he rented; but he was like Noah’s dove, he could find no rest for the sole of his foot.

Ida accompanied us. How she tore herself away from Giuseppe and the barber I never knew. In England she became but a homesick shadow of herself, refusing to learn English and belittling English people because they couldn’t speak Italian.

One day my grandfather, sorely exasperated, gave her a sum of money and a ticket to Rome. I never saw her again. No doubt she married one of her innamorati, attracting him with grandfather’s dowry.

The journey from Rome to Furness thrilled me, in spite of my continuously asking why father was not with us. My mother did not answer me, but Ida invented some story about father coming over later. Watching the landscape flash past the train finally took my mind off father, and by the time we crossed the Channel I was too excited to give another thought to him or to anyone in Rome.

I talked in Italian to everyone on the boat. That I could not understand what they said to me made not the slightest difference. Being on the sea made me very happy. It has never failed to do so. Typhoons and the worst storms imaginable have never lessened my love of the sea. When trouble has fallen upon me like driving rain, and there seemed nowhere to turn for assistance, when my health has been shattered and pain has almost driven me insane, I have made for the sea if it were possible.

Grandfather met us at Dover. He spoke the language the people had been speaking on the boat. He took me in his arms and a friendship began which lasted as long as he lived. He was the best friend I ever had. His death prostrated me, and I have never recovered from the shock of it. I was in India when he died, and the thought—absurd, of course—haunted me that he would not have died if I had been with him to nurse him.

When he put me down, after giving me a real bear-hug, I spoke to him in Italian. “Parla lei Italiano?” I asked, too overcome by the newness of him to speak in the familiar way. He smiled and answered me in Italian. “You must learn English,” he said. “It is grandmother’s language, and it is very necessary.”

“I shall learn it at once,” I promised—and I kept my word.

But I had my own way of learning it. I learned the nouns. They meant something to me. They designated something. If I wanted anything I would mention the name of it and it appeared. When I had learned the nouns, the verbs, adjectives, and other parts of speech would slide up to the nouns and would somehow stand in their right places. I have never changed my method in the study of languages. I approached even Hindustani in the same way. I cannot say that I recommend my method; but I will say that if children are interested in their studies half the battle is won. The names of things are interesting to a child, and in his eagerness to talk about them he will discover the means. When you are familiar with a language the unclamorous, quiet words will appear—words which settle down tenderly as snow; but this never happens at first.

Grandmother fascinated me—the twinkle in her brown eyes—tawny-brown with marigold rims—and her ready laugh. I fairly burned to talk with her. Fortunately she was a silent talker. She could look things if she did not say them. My Aunt Vera spoke Italian and several other languages.

The house in Furness uprose in three floors. The ground floor, with its large drawing- and dining-room and kitchen was, with the exception of the kitchen, oak-beamed and panelled. I was astonished to learn that the ground floor in England was quite as important as the piano nobile (first floor) in Italy. In Italy the servants had the ground floor, but in England everything was reversed. The servants occupied most of the third floor. In the evening, when their work was done, they actually occupied the third floor. No one came into the drawing-room with her knitting to chat with the Signora. When I could talk with grandmother she told me that it was not customary for the servants to sit down with the family. She made no comment upon the customs of either country.

Another of my discoveries was the scullery. Meals were prepared and washing-up was done in the scullery, the door of which could be shut, making, as it appeared to me, two kitchens. The first floor leaned out over the ground floor into rooms which had nothing under them but verandas and gardens. One of the rooms, the library, came down over the garden like an eyelid lowered in a knowing wink. There was some excuse for this, for the part which jutted out and swept downward held the books which, when I learned English, I was forbidden to read. Fielding and Sterne were among them, together with books on filthy magic rites and certain colourfully illustrated medical works. I read most of them, however, by hiding them, one at a time, out of doors until I had finished with them. With the knowledge thus obtained I was able to make a very grave statement when I was nine. When one of grandfather’s guests asked me what books I liked to read I electrified him by telling him, “I have read all the profane classics.” Certain members of the family still tease me about the profane classics.

Mother had a room without a scrap of colour in it. It was as white and tight as a chrysalis. You expected to see something emerge from it—a butterfly perhaps. Thinking of mother as a butterfly, I have to laugh. Aunt Vera’s room was blue, but the colour, as in fact everything else in the room, escaped your notice, for you could see nothing but the photographs—photographs of men in all attitudes, of all ages, handsome and ugly and most of them signed with some term of endearment or friendship. Men went down before Aunt Vera like ninepins—but she married the one good-for-nothing specimen of the collection. Grandmother—with her everlasting sense of humour and her refusal to interfere with her daughter’s choice—sent her a set of binoculars for a wedding present.

Grandfather and grandmother had a large room which had broken out like a rash in chintz covered with red berries. It had two big beds with lace-bordered counterpanes. During my first impression I compared them with the peasants’ beds in Italy. Grandmother never troubled to decorate the houses grandfather “took,” for she knew he would move on to another one before she could plan any embellishment. A picture of a shepherd driving home his sheep hung over grandmother’s bed. Under it was written “The Return.” I have seen these wretched lithographs in some of the splendid old houses in England, and always with the names under them.

Ida and I shared a room next to Aunt Vera’s. It also contained beds, but smaller editions of those which were in grandmother’s room. There were two green china dogs and a five-coloured mug on the mantel. There was a wardrobe with a long mirror before which I loved to stand studying my reflection. My hair was bobbed, but it curled naturally, and it pleased me greatly when Ida—having no Giuseppe to minister to—gave her attention to fastening bows on the top of my head and fussing with my clothes.

The pride I took in my appearance had a rude shock when grandfather sent Ida back to Rome, and quiet, colourless Margaret Paine came to take her place. Margaret Paine was all that a governess—who had charge of a lively Italian child—should not be. Many were the storms that raged in our room about vanity. Once I slapped her face and I was shut up in Aunt Vera’s room until I would apologize. They had to let me out at the end of the day, but I never apologized. I was not sorry, and I refused to say that I was. To this day I am not sorry. I would do it again if the occasion were the same. I had run out of the bath dripping wet to chase after grandfather who was going out. I wanted to tell him something, and I was afraid he would get away before I could reach him. Margaret Paine was horrified and as the care of me had been almost entirely given over to her she could punish me as she thought best. The family seldom interfered, but it was grandfather, on this occasion, who ordered Miss Paine to open the door and release me. She might not have imprisoned me for my nude appearance. It was the slap which set off her sullen temper—usually concealed.

Quietly and icily she nagged me while I was dressing. Her words were like little sharp stabs. My southern nature was not incensed by angry words, screaming or cursing—had I not heard the peasants, hundreds of times, abusing each other from their windows or doorways, their hands beating the air, their heads thrust forward—but nagging was new to me. I was to become better acquainted with it later when I married. The man I was to learn was not my husband, was the only Italian I ever knew who was thoroughly conversant with the gentle art of nagging.

I cried bitterly when Ida left. I felt that my last link with Italy was being wrenched from me, for my mother had explained that father was not coming to England—in any case, not for a long time.

It was indeed a long time before I saw my father again and then he did not come to England. He came to Egypt where grandfather had taken another house to pursue the study he loved—Egyptology.

Two members of the household in Furness became my dearest companions—the cat and the dog. The dog was pure dog. He was a steel-muscled creature who expressed his intolerance of described breeds by attacking them whenever they crossed his path. Someone in an ironic mood had named him Rex. I had wild romps with him every day, and I annoyed Margaret Paine—not intentionally—by allowing him to follow me all over the house. Margaret was one of those women who think that animals should be kept in their place. I have never known just where an animal’s place is unless it is in my heart. I have used my last twopence to buy food for a stray dog in the street, and I have stayed up all night to hold a hot-water bottle on a tiger cub’s tummy when he had an attack of colic. I have—yes, let me tell it—fished the big cockroaches out of the water in India and let them get away. I have never been cruel to an animal in my life with the exception of that cat, Rex’s playmate. I cut his tail off with a hatchet. Horrible—I admit it. As I tell you about it I can see his poor stump of a tail with a bandage on it trying, pathetically, to swish about.

I was lying on the floor one day playing with Rex and the cat, when something startled the cat. He thrust out his claws, forgetting that one of his paws was on my eyelid. For a second I thought his claws had penetrated my eye. In a furious rage I jumped up, took him under my arm, and carried him out to the shed where the “handy man” chopped the wood. I plumped him down on the chopping-block and cut off his tail with the hatchet. My mother spanked me soundly while grandmother salved and bandaged the poor creature’s tail. The little scar, like a tiny white pimple, is still on my eyelid. Contrary to what people might think the cat never held it against me. We were the best of friends until he died some time later in Egypt. Grandfather always moved any animals we had when he moved the family.

Soon everything was English and I was English too. I spoke English fluently. I learned, under the instruction of Margaret Paine, to subdue my voice, and conceal, to a certain extent—I have never thoroughly learned how—my emotions. Well-bred English people did not have tantrums. If they felt deeply about anything they did not mention it. To give way to grief was almost to have hysterics. This concealment of their feelings is the reason why no Englishman can be a lover. Deliver me from an English lover. Later I acquired an English husband—as a husband an Englishman is possible—but as a lover . . .

Many of the English customs seemed strange to me at first. I never could get used to the English breakfast—I still cannot understand how people can devour eggs and bacon, or kippers, or porridge and a rack of toast first thing in the morning. In Italy I had caffè-latté (a little coffee boiled in the milk) and a roll for breakfast. When I reached the age of resistance I went back to my Italian breakfast. It has always been enough for me.

I fairly haunted the library, which became, soon after we arrived, grandfather’s study. When I finished my lessons Margaret Paine took me out. While she was putting on her hat and coat I would run into the library and plead with grandfather to permit me to stay with him. Often I was successful and he would look up over his glasses and tell Margaret that he would take me out later. He seldom kept his word, for he would become so interested in explaining to me the pictures in his Egyptian books that time would slip away unnoticed. I understood much of what he told me.

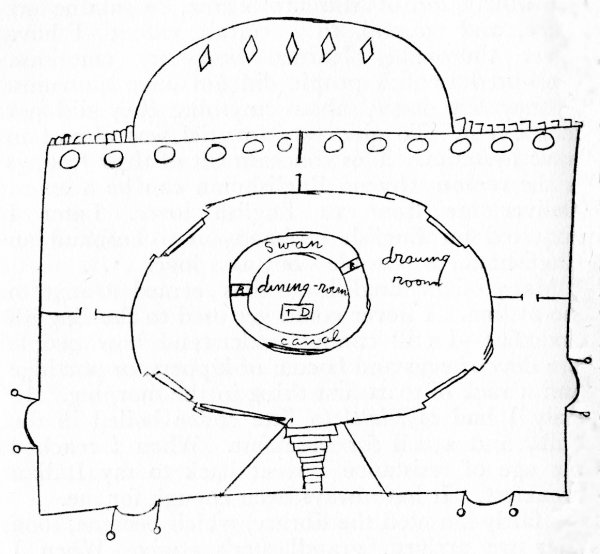

About that time, and until I was ten, I was continuously drawing the plans of buildings on every available scrap of paper. Grandfather collected the drawings and we carried them about with us for some years; but the only one which survived our wandering life is this one:

That you may understand the plan I have written the words dining- and drawing-rooms and swan canal. These were not put down on the original plan. The canal encircling the dining-room was intended for swans to swim about in. I had in my mind, although I never managed to get it down on paper, a little door opening into a passage to the cellar through which the swans could escape when they wanted to stretch their legs. The letters B indicate bridges across the canal. The letters T.D. designate a trap-door through which the servant would appear like a jack-in-the-box, with the table completely laid. When the meal was finished he would disappear through the floor and the trap-door would close over him. The circles under the dome represent windows. If any architect wishes to copy this plan I have no objection. As the patent medicines inform you on the bottles “No proprietary right is claimed.” Looking this drawing over now I think it would be a good model for some architect to follow. The circular drawing- and dining-rooms would be a change from the everlasting square and oblong rooms.

Mother and father had kept up a very animated correspondence since we left Rome. I have reason to believe that father ranged up and down the scale of entreaty, supplication, abuse and threat. Italy has no divorce law, and no doubt father ordered mother to return to the more or less conjugal bed. The upshot of the wordy war was the victory to mother. She agreed to send me to Italy for two months each year if I could be suitably looked after by some respectable member of father’s family. In fact, she thought it would be better if father did not see me while I was in Italy. Her agreement to my visits was made for the purpose of my keeping in touch with Italy and the language. I think there was something to the effect that I could decide which parent I wished to live with when I was older.

Father wanted a photograph of me, and grandfather took me to the photographer. The baby picture—there was one awful painting of a baby lying on a sofa—had been done before I could protest. I didn’t want to go with grandfather to have my photograph taken. I stormed and refused to look at the toys the photographer provided. Finally I sat down on a little stool and jammed my head against a post. A forbidding scowl must have distorted my face, for grandfather asked me, “What are you thinking about?” My answer disillusioned him if he had ever, for a moment, imagined that I was not progressing with English. “I am thinking Goddamn,” I answered. I wish I could show you the photograph of me thinking Goddamn, but I have no idea what became of it. The photographer took me with my head against the post and my brows drawn together in a straight line. No doubt he was heartily sick of me, and would have taken me in any position to get me out of his studio. Some years later, when I saw my father, he laughed about the photograph which was propped up against a vase on the mantel in his bedroom.

A box of dolls arrived one day from Rome. Their costumes were in the latest mode. They squeaked, closed their eyes, and moved their joints. I wrote a letter in English to thank father and let him see that I could write what he called “the commercial language.” The dolls gave me much to think about. I was so concerned with their anatomy that I asked grandfather why people had anything but legs. When I had explained my question and had praised the neater, more compact appearance of dolls, grandfather told me about sex. Poor man, I can see him now pulling flowers to pieces, making little designs, pointing things out on a medical chart in a sputtering effort to teach me about sex. The story of reproduction did not startle me; in fact, somewhere in my mind—rather nebulous—was the thought that grandfather was mistaken, and that people would have been better off had they been simply furnished with legs.

About this time I had one little playmate—Chester Doull. He lived near, and his Nanny (Margaret Paine would never have permitted me to call her Nanny) used to bring him to us when I had finished my lessons. I was responsible for much of Chester’s education. I used to plan the mischief and dare him to carry it out. Once, when I suggested removing the upper pastry from a prune pie and scooping out the prunes before carefully replacing the pastry, I had to bolster up Chester’s courage. I found a knife with a sharp point to operate on the pie while Chester stood at the kitchen door watching for the cook who might return from the market unexpectedly. With my grubby little fingers I scooped out the prunes and put them into a bowl, stuffing the largest ones into my mouth during the process. The bowl I carried out into the garden where Chester and I, standing behind a tree, devoured the prunes. I managed to put the bowl, hurriedly washed under the tap, back on the cupboard shelf before the cook returned. The empty pie collapsed on the luncheon table when grandmother started to serve it. “Cook has forgotten to put the prunes in,” grandmother said. Grandmother never made unpleasant inquiries at inopportune times. Later she might question the cook, but she would never have dreamt of doing so at the table. I never knew what she said to the cook—if anything; but the epilogue of the pie episode was tiresome enough. There was a dish of prunes on my supper tray (my supper was prepared by grandmother, and eaten in the room I shared with Margaret Paine) every evening until I hated the sight of a prune.

There were very few children in the neighbourhood, so I invented a family of children to play with Chester and me—perhaps I should say to act as scapegoats for our naughtiness. The family name was Makaksy, and the seven children were named as the days of the week. Wednesday Makaksy was the most unruly. In fact, he stopped at nothing, from stealing the icing off cakes to playing rather disastrous jokes on the family. The cook told me that “if ’e came into ’er kitching a’ stealing she’d smack ’im good and propper.” But she never caught him; Wednesday saw to that. Sunday Makaksy was a sweet, spineless child who never dirtied her clothes, and who went to church with her father and mother and actually put her penny on the plate. We had very little use for her however. We called her a tell-tale, for one so perfect must have “told on” Wednesday. Monday, Tuesday and the others simply followed Wednesday. He was the ringleader. His Atlas shoulders must have ached under all the blame we put upon him. Mr. and Mrs. Makaksy were shadowy beings necessary only as parents for their calendar seven.

One rainy day, when I was kept indoors because I had a slight cold, something occurred which was supposed to throw a light—not by any means a rosy one—on my character. I was in the library with grandmother. Grandfather had gone to London with mother and Margaret Paine. I had helped to wind wool, to thread needles, to match buttons from a helter-skelter assortment of buttons and hooks in a box. I was aching to go out. I had suggested all manner of excuses for going out. They were promptly turned down by grandmother. Wearily I wandered over to the window where big drops of rain had caught on the casement like a string of crystal jewels. One big raindrop trickled slowly down the pane. In it, tiny, infinitesimal, the garden lay. I followed it down the pane with my finger, excited about the garden tucking itself into such a small mirror. At the lower sill the garden slid out of the drop and disappeared. I told grandmother about the little lost garden and she told me a fairy story about a water sprite. When she had finished the story I said: “Do you want me to tell you a fairy story?”

“Yes, dear,” she said, “tell me a fairy story.”

I began: “Once upon a time there was an angel who lived in a beautiful garden of apple and pear blossoms. The garden was all blossoms and the angel was very proud of it. There were two children, a little boy and a little girl, who loved the blossoms because they were so beautiful. One day the blossoms were more beautiful than ever and the children had to have some of them. They climbed the trees and picked some, but when they were getting down the angel came from behind a cloud. She had a pail of water in her hand, and she threw it on the children.” Then I asked grandmother: “Don’t you think the angel was very wicked to throw the water?”

“Yes,” grandmother said, “she should have allowed the children to take some of the blossoms.”

She changed her mind a few days later when old Mrs. Angel, who lived on the next road, complained of Chester and me stealing the blossoms from her fruit orchard. It was not the theft which grieved grandmother so much as the cunning way I made her commit herself in advance. She had placed me beyond punishment by saying the angel should have allowed the children to take some of the blossoms. “A child who can tell a story like that will bear watching,” Margaret Paine said when she heard about it. Although grandfather said nothing I am sure his respect for my intellect increased, for he took much of my education upon himself after that. “The child is quick,” I used to overhear him telling grandmother, “quick on the uptake.”

I am sure mother thought—while she never admitted it—that all my devilry was a gift from father. The apple blossom episode was not indicative of my character, for many times I have taken the full brunt of circumstances which I could have avoided by seeing to it that people show their hands in advance.

The day came when I had to go to Italy to fulfil the agreement made between father and mother. The entire family came to London with me. Margaret Paine was to have a holiday until I returned, and was to stay on in London. There were tears in grandfather’s eyes when he said good-bye to me. At that moment my heart sank and I clung to him begging not to be sent to Venice. Then I saw him smile determinedly and he told me not to be silly. I made a brave front for something in me always sought grandfather’s admiration.

It had been decided that I should visit my father’s two aunts who lived together in Venice. I had never seen them, but I imagined—and rightly, as it turned out—that their home would be deadly dull. They sent their solicitor’s clerk to fetch me. He made very clumsy attempts to help me dress and undress the day and night he had me in his charge, until I rose in my wrath and told him that girls of five could dress themselves. My attempt at my own hairdressing rather gave my brave words the lie, and he had to get the parting straight in my defiant mop. One thing I shall always remember him kindly for was allowing me to eat all the things I was not supposed to have. I had a wonderful tuck-in on the train.

The gondola fascinated me. In fact, I had insisted upon it when he tried to steer me into a motor-boat to save time. I remember wishing that Chester was with me to enjoy the fun.

The aunts lived in a palazzo on one of the smaller canals. How thrilled I was to see boats going right up to the front door. How wonderful, a city without streets. I was to learn later that Venice had streets, if narrow, and that one could walk all over the city.

The aunts were waiting on the steps when the gondola glided up. They kissed me effusively in the Italian way, and discussed between themselves my resemblance to father. Father was one of the very fair Italians. His family had married into fairer nations and father, in appearance, was like his blond relations. I also am blonde; a fact I have detested in adult life. I began to detest blondness in childhood when I discovered that all father’s beauties had glorious dark eyes and midnight hair. Father’s beauties, however, have nothing to do with my present dislike of the fair. I think of blonds as red people, too highly-coloured, too obvious, too pitiful when Time tramples them under his feet. Many a night I have sat on the roof of the Peking Hotel and watched the West dancing—the reddish-skinned West, big-footed—big-handed—rather breathless—too excited. Then I have watched the slender, graceful Chinese gliding through the dance—their ivory hands like long-petalled flowers—wax-white jasmine in the blueness of their hair. Then against an over-florid Dutch background I have watched the dark, pointed, witch-like beauty of Java moving mysteriously, scarcely touching things—like the curl of incense smoke. You get what I mean, don’t you? You may not agree with me; but let me tell you, gentlemen do not prefer them. I should know. The only thing I am thankful to the blond colouring for is a good skin. Truly I have that. No amount of abuse can hurt it. I could wash it with Rinso or “monkey soap” without injuring it. On my body it is of the same texture as on my face. I promised to tell you everything; but I must get back to the aunts.

You may see a thing with rapture or disgust, it is the way you see it that counts. There was something wrong with the way I saw the aunts. I thought they were about a hundred. Actually they were not much over fifty, but they seemed years older than grandmother or grandfather. They had practised nothing but austerity and the art of prayer and it had given them that smug, righteous look than which there is no whicher. The house also was smug and righteous. The first thing they showed me was a stained-glass window which had just been installed half-way up the stairs as a sort of monument (there were others in the cemetery) to their brother who had recently passed on, leaving them the family fortune. In all the colours of the rainbow a shepherd stood beside his flock, holding a lamb in his arms. His long crook rested against a slender tree which looked but little larger than the crook. The sunlight streamed in through the bits of glass, touching the stairs and the reception-room below with multi-coloured rays. “Che bella—bellisima!” one of the aunts exclaimed. I could see nothing beautiful about it. The two women stood on the stairs and literally raved about the beauty of the window. They explained it to me. The stories of the Good Shepherd and Christ blessing little children were somewhat mixed in their endeavours to impress me with its beauty. Child that I was I realized there was no getting up the stairs until I admired it. I began to lie about the beauty of it; but I hated it from that moment. I had no idea then that it was going to release me from the purgatory of visiting the aunts for all time. We three passed it with something akin to reverence. Theirs genuine. Mine feigned.

They took me into a big bedroom, furnished, as most Italian rooms are, with but little furniture. A huge bed, very carved, very heavy, very stiff, waited, all made up with fat be-laced pillows for my little body. It looked so big and lonely I wanted to cry. I remember biting into my lower lip to keep from sobbing. One of the aunts decided that I must have a bath after the journey. The other one went downstairs to talk with the solicitor’s clerk who was still waiting.

When I was undressed the aunt looked at me in amazement. “They are not allowing you to wear the scapular—or anything,” she said. It was my turn to look astonished. “After your bath,” she promised, “I shall get you one.” She did. She got me three as a matter of fact, the scapular and two little medals. As she hung them round my neck she told me father would be shocked if he knew I wasn’t wearing them. I almost laughed in her face. I knew my father didn’t wear them, and I also knew—or perhaps I felt—that religion, or anything pertaining to it, left my father cold. When she told me that Saint Anthony would help me find anything that was lost, if I wore him, I wondered if he would help me find my way back to grandfather. I asked her if father would come to see me. She told me what I already knew, but didn’t want to believe, that it had been decided father would not see me while I was in Italy. Of course, when I was older, no doubt I would come to Italy and live with father—she hoped.

When I was dressed I was taken downstairs. We halted again before the window to admire it. The aunt pointed out new beauties and embellished the stories they had already told me. She told me about her brother, my great-uncle, who had died without seeing me. He would have been so happy if he could have seen me. Just why she didn’t say.

I arrived on a Saturday afternoon. I sat in the reception-room with them—the solicitor’s clerk had gone—listening to the virtues of my departed great-uncle, hearing about St. Mark’s Cathedral where they would take me the next day. What could I tell them about God? Nothing, of course. I have always thought that it is easy to believe in God if you don’t have to explain Him. As I look back on that conversation one of the aunts seemed to have been controlled by someone very far away as the tides are controlled by the moon. I suppose it was God. I kept trying to get them to talk of my father. But they were evasive. Father was away—travelling—they were not quite sure.

Perhaps he had gone with one of his many mistresses. I know now that he had quite a number at that time; but I doubt if he ever kept his word to any of them—his word given in passion. He inspired so much passion, but—excepting my own devotion—I think he inspired little love. It was natural for such a man to be unhappy in marriage. No woman, equally frivolous, can cover as much ground as a roué. There are more hidden traps in her personality—more longings to capture her. There was nothing frivolous about mother and no passionate longings. Mother travelled a very straight road, but nowhere on it could she and father meet.

The aunts questioned me about life in England, about grandfather and grandmother, and very tactfully about mother. To some of my answers they looked at each other and nodded their heads.

I had supper with them. It was served by an old woman I wanted to run to and put my arms about—yes, and cry. Old Bianca seemed to be the one really human person in the house. She had the ample peasant bosom which children like to cry on and the kind eyes which children trust. I was hoping she would put me to bed; but instead it was one of the aunts who tucked me up, kissed me, and criticized ever so slightly the prayer which Margaret Paine had taught me, and which, hastily, I tried to translate into Italian. I had a good cry when she left me, and with St. Anthony pressed into my neck I implored to be allowed to find my way home at once.

St. Mark’s interested me. I loved its bizarre Oriental appearance; its gilt horses and lions all out of proportion because, as an aunt explained, the Venetians had never seen animals. In later years, when I have visited St. Mark’s, I have looked in vain for the screen with the Virgin painted on it before which I stood taking in every detail of her costume and wondering if I could have a dress like that when I got married. I suppose the screen is still there, but I have not rediscovered it. The aunts tried to amuse me. I am sure they did their best. They walked me through the narrow streets pointing out interesting buildings, and telling me bits of their histories which they tried—and, worse luck, I knew they were trying—to adapt to my understanding. I have always had a high opinion of my own intelligence and I am intolerant of those who try to prepare their statements for me. This sugaring of the pill, more than anything else, turned me against the aunts. From the first moment they had undertaken to give me a bath, to help me dress, to treat me as if I were a baby. My recently acquired knowledge of fastening hooks and snaps, getting the seams of my stockings perfectly straight, understanding although I didn’t quite believe it—about sex, fiercely resented the attitude of the aunts. When I was in the house I made little models of the buildings I had seen out of cardboard. Some of them I coloured with a box of paints one of the aunts gave me. One day, speaking about colour, she told me I could learn how to blend colours by studying the window. The window never got very far from our conversation.

One aunt played the ’cello. Her music—I have since heard that she might have been a famous player had not the death of her maestro, with whom she was in love, put an end to her serious study—was the only thing in the place I liked. I used to plead with her to play; and when she agreed I would sit at her feet, forgetting for the moment my homesickness.

It occurred to me that St. Anthony was going to do nothing for me. I thought of getting sick but I didn’t quite know how to manage it. One day out of a clear sky my release came. Impulse has always served me well. It is only when I plan too carefully that I fail in my design. I have taken some desperate chances, but I was desperate when I took them. Homesickness, the dull routine of the aunts’ house, and, above all, the window, acted upon me like the stinging lashes of a whip. Daily they goaded me on to desperation.

Let me arrange the scene for you as it was on that day of days. We were sitting in the reception-room waiting for Bianca to tell us that supper was ready. The late afternoon sun came in through the shepherd and his flock and crept down the stairs. It touched the hair of one of the aunts. I can see it now—the light on her head. The other aunt knitted some blue woollen thing. I was sitting on the floor making little gondolas out of cardboard. Once in a while one of the aunts would look up at the window and call attention to something she hadn’t noticed before. “I am glad we could have it placed so low, so near the landing,” was the last thing I heard about it.

Suddenly I dropped the scissors, flung away the cardboard, dashed up the stairs and kicked my foot through the window. For a second I stood there trembling, frightened out of my wits, then I turned on them like an animal at bay. I have no idea what I expected them to do. They were speechless. One of them worked her mouth like a fish out of the water. No words came. From that inarticulate state she promptly screamed her way into hysterics. The other aunt was sobbing loudly as only Italians can sob. They fell on each other and wept into each other’s necks. “Povero fratello!” (poor brother!) they kept repeating. When the storm subsided, they spoke to me. They told me I had no respect for the dead. My poor unfortunate father would die of grief when he heard of it. My mother would know at once what I had done. They would telegraph her. Their abuse left me cold, but I pointed my ears when they threatened to telegraph.

One of them managed to pull herself together and call for the gondola. She started for the telegraph office while the other one told the servants, who were standing in the doorway waving their arms about, of the curse I had brought upon the house. I think I wondered what Margaret Paine would have thought of the emotional show.

Old Bianca took me upstairs and brought me some supper. She kissed my cheek when she set the tray down. I am sure she thought me very depraved, but she was sorry for me. I took my clothes off and got into the big bed. Soon I was asleep. Childhood doesn’t worry over its depravity.

I was awakened in the morning by the aunt who had gone to the telegraph office. Leaning over the bed, she hissed, “Your grandfather is coming to fetch you. We have had an answer.” I could have kissed her. I could have screamed for joy. Grandfather was coming. I would have kicked out all the windows in St. Mark’s to see grandfather again—to go home with him. Perhaps, after all, St. Anthony had his own way of answering prayers.

Grandfather lost no time in getting to Venice. It was his turn to erect the departed uncle’s memorial. He settled with the aunts for the havoc I had wrought. The settlement must have been arranged quite amicably, for the aunts stood on the steps while the gondola bore us away smiling and waving their handkerchiefs.

Grandfather never mentioned the window until we were in the train, and then he said: “ Gervée, why did you do it?”

I put my head down on his shoulder and said—was I always the coquette?—“Because I wanted to be with you again.” He hugged me and patted my head.

Utterly spoiled, you will say. Yes, no doubt I was utterly spoiled; but I loved him with a love the years cannot dim, and this is not because he let me have my way in most things—others have done that but, with few exceptions, I haven’t loved them. My stormy heart has often been in love, but that is not the same thing.

I had stayed less than one month of the three I was to spend in Italy. I was never sent back. I believe, down in her heart, mother was glad I broke the window. I have always liked fine terminations, but the window was the most definite ending I have ever put to anything.

My mother caused the disappearance of St. Anthony, the other medals and the scapular. I never knew what became of them.

Chapter II

When I was nine, grandfather took a house in Egypt—in Aswan. He had been travelling back and forth to Egypt for years to pursue his studies in Egyptology. He had rented the house before on previous occasions and some of his furniture, which survived the comings and goings of other tenants, still remained there.

Aunt Vera did not accompany us. For some time she had had her mind set upon going to Canada to live on a ranch with a woman friend who held out glowing possibilities of she and Aunt Vera managing the ranch together. Aunt Vera was the last person in the world to consider farming of any sort, but she had to learn her limitations by experience. She left all the suitors—one followed her later, the one she married—and started out in a whirl of excitement about the fortune to be made in grain, apples and poultry.

The library, which belonged to grandfather—everything else in the Furness house belonged to the owners who had rented us the place—was packed into boxes. Crates were made for Rex and the cat, and we were ready for the journey. We were always ready to fold our tents like the Arabs and quietly steal away. We travelled light unless our animals were too numerous. Often when I have gone about the world with the fatigue of four or five huge wardrobe trunks, I have longed—but not enough to achieve it—for the simplicity of the early days.

I was bursting with excitement about going to Egypt. I would ride on a camel out into the desert. I would see a mirage—what a lot of them I have seen!—and beautiful ladies who looked like Cleopatra. I would climb the pyramids, inside and out. I would see the sphinx by moonlight. No one had ever seen it by any other lighting in the novels I had read. I lived in a dream scarcely hearing what anyone said to me.

Margaret Paine stayed in England. She was of the sort who never could live out of England. Like many of the good old Islanders, she had no use for a foreigner. I bade her good-bye with something approaching rapture. I had never liked her and I was glad to see the last of her. Mother seemed pleased to put greater distance between herself and father. She had told me, soon after I returned from Italy, that it was not necessary for me to keep up my Italian. I kept it up, however. I used to go out alone in the garden or for walks and talk to myself in Italian. I taught Chester to speak it after a fashion and we used to tell each other secrets in it. I didn’t want to leave Chester. I begged grandfather to take him with us. I even went to his mother and asked her to let us have him. He cried bitterly when his mother would not consent. He gave me five little turtles as a parting gift. Fearing that grandfather, at the last moment, would find no way of moving them, I put them in grandmother’s trunk under a lace dress. I was to learn later that turtles, in such close confinement, did not travel very well. The odour they left after them clung to the trunk for years, and grandmother’s lace dress had to be burned.

The Mediterranean reminded me of a big bowl of setting jelly. I knew that if I had a spoon and could bend way over I could dip up thick wiggley spoonfuls of it. Breathlessly I rushed from one side of the ship to the other, hoping some big fish might poke his head up through the jelly. I never tired of watching the flight of the sea-gulls and the way they could sit on the water, tossing up and down as if they were on little springs. The only passenger I remember was a lady who let me exercise her dog on the forward deck before breakfast. No matter how many chocolates she ate she seemed always to have a full box. She was very generous with the sweets and I liked her accordingly.

Port Said was like a fairy tale. Its dirt and cheap bazaar streets were enchanted. I knew genii would run out of some doorway and turn into animals or birds right before my eyes. Grandfather bought me a pair of sandals and a box of the inevitable turkish delight, which mother promptly took possession of, to deal out in small doses. I was disappointed at not finding the pyramids at Port Said. I had some vague idea that all the wonders of Egypt were huddled together in one spot. I was not to see the pyramids for some months, for grandfather hurried us through Cairo, as he had hurried us through Port Said. We stayed one night at Shepheard’s Hotel. What impressed me then about Shepheard’s was the size of the rooms and the corridors. The size of the veranda, where all the world meets, was to occur to me later.

The train journey up to Aswan was thrilling—the desert and the Nile. Lines of camels passed along the desert. They were caravans with hidden treasure going to some beautiful princess. Perhaps a barge would come floating down the Nile with a silver sail like Cleopatra’s.

Our house in Aswan was an old rambling affair. A rich merchant had built it for his son who had little use for it, preferring to live in Europe. It had some gorgeous carpets on the floors and walls. Some of the walls were covered with the Bedouin hiam (tent cloths). The rooms seemed to be all hangings and coverings. The furniture was of the inlaid, pettily-carved Arab sort which I have learned to despise. Even then I resented its fussiness. The beds were big divans with good mattresses. Grandfather had bought them on a previous visit. Bookshelves waited empty, round the walls of one huge room, for our library. There were bathrooms without hot water; but hot water was never lacking. The boys were for ever heating it on kerosene stoves. The servants, who greeted grandfather and grandmother with their hands on their foreheads and their hearts, were unloading furniture from a cart when we arrived. It was the extra furniture grandfather had ordered before leaving England. It seemed to consist of tables, writing-desks and dishes. The house soon filled with Arab servants. They appeared almost to be in each other’s way. When I got to know them and where each belonged, they fitted perfectly into the routine.

A room on the first floor was fitted out as a schoolroom. There were a large desk with a chair before it, a small desk—it also had a chair pushed in under an extension—a long table, several maps which shared the walls with a blackboard, and a book-case which turned round on a pivot. On the train grandfather had told me that I was to have a tutor from Cairo; an old friend of the family, a certain Mr. Vanburgh, who, no doubt, temporarily pinched by poverty, was willing to undertake my education.

There was a garden with a wall round it. The Nile mud had been brought to it and put down over the sand so flowers and small shrubs could grow. In one corner, tall date palms plunged their feet into the sand until they could feel the moisture below.

We had been in Aswan but two days when Mr. Vanburgh arrived. I have never seen anyone since so haggardly handsome. His face had passed through all the phases of decadence. There was something about him which spoke of spiritual assassination. Of course I had no idea of all this at the time. His face simply fascinated me then because it was so different from any face I had seen. He had strange dark eyes and an exaggerated charm. For women his appeal had been swift—so I heard mother tell a lady who visited us later. Even as a child I felt that he would always be master of the situation—that he might make intelligent mistakes but not foolish ones. I wondered if he would be victor in a clash of wills and how I was to get my way with him. Looking back at him I think he was a man who could unhesitatingly commit a murder, but who would consider for some time which woman he would go to bed with. His voice was rich and deep. It seemed to bore down through his words. He had never tutored anyone before. He had been married twice, but he never spoke of his wives. I think they had shuffled off this mortal coil and left him free. He was just under forty when he came to us.

He, with grandfather’s help, educated me. They had their own very definite ideas about my weird education. Their interest in Egyptology was so intense that sometimes they forgot me entirely. Mr. Vanburgh—the name did not belong to him, he used it for reasons of his own—would forget to come to the schoolroom. I would wait a reasonable time, and then, knowing Egyptology had first place, I would go out into the desert. Grandfather used to send me out to walk to cultivate my observation. I had to write down what I had seen during my walks, and the impressions caused by what I had seen. Little rewards were given me for learning chapters from the Bible, and pages from the Vedas and the teachings of Buddha, the rewards were given for my memory and not for learning the religious teachings. As a matter of fact Mr. Vanburgh frequently made fun of the teachings. He cursed me, very elegantly, when my mind refused to absorb as much as he thought it should. They kept me up all hours of the night—regardless of mother’s protestations—teaching me Egyptian history.

Grandfather, with all his colourful imagination, reconstructed the tombs and the temples. Mr. Vanburgh insisted upon rather difficult mathematical problems. The simple arithmetic which Margaret Paine had taught me in no way fitted me for the demands of Mr. Vanburgh; but somehow I managed to stumble through what he required. He gave me lessons in Latin and he threatened me with Greek. I invented little ways of learning Latin because I could not, under his direction, learn the nouns first. I also invented rhythms for adding up columns of figures. I still use them. They are composed of beats and stops, but to save me I cannot explain them.

Grandfather and Mr. Vanburgh decided to write a book about Egyptian sculpture. When either thought of something concerning it he would rush to the study, leaving whatever he happened to be doing, and make a note of it. This happened sometimes when they were at the table. When they returned later, sometimes an hour after jumping up and running out, they expected to find their meal still waiting for them. The servants were usually prepared for these flights and returns. One evening when Mr. Vanburgh was greatly inspired, the servant, thinking he would not return, because he delayed much longer than usual, threw his food—the inevitable Egyptian mutton and braised tomatoes—into the garbage pail. When he returned the servant smiled, as only an Egyptian can on such an occasion, and explained that he had taken the food out to the kitchen to keep it hot. I followed him out and watched the cook fish it out of the garbage pail, and titivate it a little with some fresh parsley.

I sat at the table and laughed inwardly while Mr. Vanburgh ate it, wondering what he would say if he knew where it had been. I remember the little thrill I had thinking how neatly he had been tricked.

The book on Egyptian sculpture was privately printed by them and given to their friends.

I learned Arabic from the servants and the Arab children. I learned it in my usual way by acquiring the names of things and learning to describe them afterwards. Grandfather, who spoke fluent Arabic, often corrected me; but I don’t believe he knew how I acquired the language. He was never concerned with the why and the wherefore of things. If they happened, why worry about their instigation?

I was lonely for companions of my own sort. The Arabs were very interesting but I longed for Chester. I wrote letters to him almost every day and told him with a certain amount of pride about my studies and the progress I was making. But I was not to be left long without companions. Grandfather’s house soon became a caravanserai for all sorts of wandering people. They came singly and in groups. They brought their children and their servants. When the house would not hold them grandfather hired a place nearby. Grandmother for ever played the rôle of hostess. Several men made languishing eyes at mother but they made not the slightest impression. Mother was like a certain religious cult of India; she retained her magnetism by permitting no one to contact it.

A French lady, Mme. Devereaux, came to visit us and brought her son and daughter, Georges, a boy of twelve, and Azele, a girl of ten. Georges kissed my hand and clicked his heels together when he met me. I had seen the men in Italy kiss the ladies’ hands hundreds of times but I had never seen little boys kiss the hands of little girls. It did not embarrass me—nothing has ever done that but squeaky shoes—but I wrote Georges off as a “sissy.” Azele was very pretty, very charming, very intelligent, but destined never to catch the eye.

Mme. Devereaux was a widow. Her hair was slightly bleached, her face was slightly made up; everything about her seemed slightly done. Her voice dripped like honey in a thin, sticky smear. She gave the impression of being very frail, very helpless; but, judging from what I have heard of her since she must have been as calculating as a harlot. Then she seemed as cool and dispassionate as a pearl and she reminded my childish mind of a picture I had seen of a saint.

Georges and Azele told me about Paris. There was no city like it in the world. They had been to a dancing school. I insisted upon their teaching me to dance. We would take the gramophone into the library when my lessons with Mr. Vanburgh were finished, and Georges would teach me the steps while Azele put on airs and criticized my movements. What she said made no difference to me. I was going to learn to dance and learn I did—all that Georges could teach me. In exchange for his dancing lessons and Azele’s hints on how to wear my clothes to the best advantage I told them about Hadrian’s visit to Egypt in A.D. 130. I made much of the story of Antinous, Hadrian’s beautiful youth who threw himself into the Nile as a sacrifice to the River god. I pictured Hadrian as inconsolable until he erected temples and renamed the old city of Besa, Antinoöpolis in memory of his favourite. When I told them there was a bust of Antinous in the Louvre, they said there was no such thing or they would have seen it. Then I told them that Queen Hatshepset had married her brother, Thotmes 2nd. Azele said there was nothing wonderful about that, why shouldn’t you marry your brother if you wanted to marry him?

I showed them grandfather’s collection of ushabti, libation cups, funerals jars and scarabs. I took down a strigel from its place on the wall and explained to them that it was used to scrape the hair off the body during the Greek period in Egypt—I insisted upon showing them just how it was used, and Georges extended his leg—putting his foot in my lap—for the operation. The instrument was too dull to shave the hair off his leg, which was as well, for had I been able to use it, I would have done a thorough job while the mood to demonstrate was upon me.

Sufficiently to impress them with their own ignorance—and no doubt to get my own back on Azele for laughing at my dancing—I recited the longest chapters I knew from the Bible. In a way, I felt very superior to them. Their knowledge seemed very frivolous to mine.

I had an Arab pony whom I used to ride into the desert, and when I was far enough away from the village I would cease to control him and let him gallop wherever he liked. We would fly like the wind over the sand, he snorting and drinking the wind, I screaming to him to go faster. Why I was never thrown is a mystery. Perhaps my utter fearlessness saved me.

Grandfather got a pony for Georges and one of the Arab boys taught him to ride; but I don’t think he enjoyed it. Conventional riding in his beloved Paris might have appealed to him, but a frisky Arab pony on the desert was too uncertain. Azele was afraid of horses and nothing would induce her to mount.

Before Georges left he told my mother how I rode and she forbade me to ride unless Mr. Vanburgh accompanied me. Inwardly I resented this; but I soon won Mr. Vanburgh over to my desert gallops. Then we would race each other, making bets on which horse would arrive first at a certain place. I usually won for I had the faster horse.

Grandfather planned a visit to the pyramids for all his guests. A desert sheikh who owned a dahabeeyah offered us the boat for the journey down to Cairo. We stopped on the way down the Nile to visit Luxor. Grandfather had taught me to call it El-Aksur as the Arabs did. His guests followed grandfather like a lot of sheep in and out of the Theban ruins. He explained the festal scenes which are depicted on the walls of the great colonnade. He stood before Amenhotep’s temple, telling us that the building had been rather neglected during Akhenaton’s revolt—when he refused to worship the sun as his ancestors had done—and Tutankhamen had to take a hand in it. I hung on his words like a spider to his thread, but some of the others, almost baked under the hot rays of the sun, had tried to find a meagre shelter behind the broken columns.

For some obscure reason I thought that the great statue of Rameses would move if I watched it long enough. I stood staring at it until one of the ladies told my mother I would surely have a sunstroke. Mother knew better, but she suggested our getting back to the boat.

Mr. Vanburgh had suddenly become very attentive to mother to save himself from the vamping of Mme. Devereaux. Mother, not knowing what inspired his sudden interest, was rather impatient with him. His gallantry would have passed me by too, had not Georges whispered to me that his mother had her eye on Monsieur.

Cars—summoned by a telegram to Cook’s—were waiting for us at Cairo to take us out to the Mena House where grandfather—with the aid of another telegram—had ordered dinner. The garden of the Mena House impressed me then as it has always impressed me—an oasis on the edge of the desert—a cool, green haven where the sting is taken out of the sun by the palm trees and the flowers, and the blossoming shrubs make you forget the miles of trackless sand which lie just over the wall.

We had dinner in the garden on small tables under the trees. An orchestra was playing on the veranda. It all seemed very theatrical, like a painting hung up somehow on the wall of night. Outside the wall it was dark, that blue dark of Egypt. The painted garden seemed to make a hole in the depths of it.

After dinner we went to the pyramids. I could see nothing but a vague outline of them in the dark. There was to be none of the customary moonlight to light up the sphinx. Someone, less romantic than myself, had known that if there was no moonlight to shine on anything else, there would be none to shine on the sphinx, and had brought along a magnesium flare. He touched a match to it and suddenly the sphinx rose out of the desert. It seemed to stride towards us through the shadows. Behind it there was a blue drop with yellow stars sprinkled on it. I saw the great stone face with its broken nose, its full negroid lips, the flush on its cheeks which time cannot obliterate, the reverie in its eyes, the scars on its chest where the excavations had wounded it—and then it was gone—gone back into its mystery.

I was crying. I felt the tears cold on my face. I slipped down on the sand and sobbed. I knew that no one who had seen it under the moon had seen it as I had—for just as it vanished it was opening its lips to say something. I was roused by a voice saying: “Madame wants her fortune told?” Right near me, I could have touched them, Mme. Devereaux and an Arab, Abu Bakt (a fortune-teller, literally the father of luck) were standing.

“How can you tell it here?” she demanded.

“I have the candle,” he said.

He raked the sand into a little heap with his hand and set the candle on the top of it. He crouched down and poked holes in the sand with his finger. “Your husband will be very rich,” he said, “and you will have many children. All will be boys. One will be rich like his father and travel to far lands.”

“You silly fool!” Madame said, “here are two piastres, quite enough for you.” She threw the coin. He found it in a second.

I sought grandfather and soon he shepherded us back to the hotel. Camel boys and dragomen followed us back, hoping we would engage them for the next day.

All night I dreamt of the sphinx. Once it was dancing on the desert with one of the pyramids, its scarred chest bleeding profusely. I must have been talking in my sleep for my mother—I had a bed in her room—woke me and asked me what was the matter. I sat up in bed and told her about my dream, and I tried to explain to her how I had felt when I saw the sphinx. She told me not to be silly. At such times I used to hate her when I was a child. I know better now. Who can change the temperament of another?

The next day I rode a camel. I felt a little sick from the swinging motion, but not for the world would I have admitted it. Georges sat on another gaily-bedecked camel also trying to pretend the motion did not upset him. Azele rode a donkey whose fleas kept her occupied with scratching. Grandfather and Mr. Vanburgh, on camels, accompanied us. A camel-boy walked beside my camel telling me how easy it was to climb the big pyramid (Cheops) on the inside. After riding round the pyramid we got down, or the camels did. Snorting and sputtering, mine lowered himself ever so slowly. Unpleasant things should be done quickly, but he believed in drawing out the agony. I have often wondered why these beasts can get up so much faster than they can get down.

After a lot of persuasion grandfather consented to allow Georges and me to climb the pyramid, the camel-boy going ahead to show us the way. We carried lighted tapers. Much of the way we had to crouch down and almost go on all fours. The chamber of the king being about eighty feet above the chamber of the queen was as nothing to our curiosity. Eagerly we took it in our stride—or rather our crouch. We were disappointed in the chambers. I am a little uncertain as to what we expected to see. The camel-boy explained that the chambers were empty because the king and the queen had been taken to the museum. I scratched my name on one of the stones of the queen’s chamber with the snap that kept my hair out of my eyes. Georges scratched his name with the same instrument. The stone was very hard. I could write only on the very surface of it. Its resistance was recalled to me six years ago when I tried to rent a house in Misr-el-Ghedideh (Heliopolis). Thinking the stones of the floor looked a bit crumbly I asked the Egyptian owner: “Will the floor last?”

“It should,” he answered, “as the pyramids were made of the same.”

Georges and I made up a story, as we crawled down the pyramid, to tell Azele. The mummies of the king and queen were to be in their chambers, with the mummies of their court wearing gorgeous dresses and jewels. They were to have hands and faces of solid gold. Later in the day we told her this story. She insisted upon going back to see the dresses and the jewels. She would endure the climb to see them. She went to grandmother about it. Grandmother, who never in her life failed to see a joke, told her that she must take advantage of things as they came along and not be so frightened of soiling her dress.

I have reason to think that the French family was beginning to get on grandmother’s nerves.

The next day there was a trip planned to Bed Rachine. We children were not taken because grandfather wanted to visit a famous psychic who could extend his vision round the world and lay bare all the hidden secrets. Later, on one of my many journeys to Egypt I visited him. I saw nothing remarkable about him. If he had any power he concealed it the day I saw him.

Mr. Vanburgh stayed at the hotel with us. Towards evening he took us to El-Ahram, the little village near the pyramids. An Arab came out of his tent and made coffee for us in the sand. He dug a hole, made a fire in it, and set the coffee-pot over it. His wife, who wore a yashmak of gold coins, stood in the opening of the tent holding the dirtiest child you can imagine. The poor little mite had sores all over his body—a rash brought out by filth—and matterated eyes on which the flies had settled.

In spite of the gold cascade the woman told us they were very poor. She tried to beg a dress for the baby who had no clothes. How the fastidious Mr. Vanburgh managed to drink the coffee I can’t imagine. He rinsed the cup out well with the boiling mixture before he swallowed any. The Arab brought out two boxes and they sat themselves down and discussed politics. Mr. Vanburgh was a sly old dog who nosed out information from all sorts of sources.

Georges tried, unsuccessfully, to wedge his way into the tent while Azele stood off holding her nose. I asked the woman how old she was. She told me she was fourteen and that she had had another baby. It was dead. She let me pass inside the tent. I suppose this was because I spoke Arabic and she wanted to question me. I answered all her questions and then I decided to question her. “Does it hurt much to have a baby?” I asked her.

She shrugged her shoulders. “Not too much,” she said. She made confinement something quite commonplace and uninteresting. There and then I decided not to have children.

Mr. Vanburgh, having squeezed the Arab dry, called us and we went back to the hotel. My mind still hovered round what the Arab woman told me. Having a baby should at least be dignified by joy or suffering; but instead it was like putting on an old shoe. No wonder the Arabs had so many children. There was nothing to it. When grandfather had explained sex to me he had failed to tell me how easily you had a baby.

That night we watched the dancing in the dining-room. We lingered over dinner as Mr. Vanburgh said nothing about us going to bed early. He, too, seemed to be interested in the dancers. I watched girls in the arms of their partners and wondered if they loved the men they were dancing with, if they would marry them and have babies.

We were in bed and asleep long before the others returned from Bed Rachine. I had intended asking mother about the Bed Rachine pyramids when she came up to bed. Never would I have dreamed of asking her to corroborate what the Arab woman had told me—but I slept soundly and didn’t know she was in the room until the boy brought our tea up in the morning.

We returned to Aswan by train. Grandfather’s guests left singly and in little groups as they had come. Mme. Devereaux, Georges and Azele were about the last to leave.

The house was quiet for a while and then a new assortment of people arrived. They brought no children with them. The youngest of the new guests was a Russian named Peter Evenoff. He was probably about twenty. I fell in love with him, not because he attracted me, but because I thought I should be in love with somebody. No doubt the almost child marriage—although nothing like India—of the Arabs made me think I should give some thought to marriage. I was not very keen on it. I thought it rather foolish; but remembering what the Arab woman told me, I thought, even if humdrum, it would not be difficult.

The Arab women preserve the evidence of their virginity. In fact, this piece of a torn sheet, is usually their most cherished possession. I saw one of these sacred relics at one of the Arab houses. When it was explained to me, I wanted to know if every woman was a virgin until she was married. On being told by an Arab woman that this was a fact, I asked her if she thought I was a virgin. She assured me that I was. I became rather interested in myself and I wondered if Peter Evenoff had any idea of the mystery I concealed. I am sure Peter thought of me as a precocious child—if he thought of me at all. I used to imagine myself kissing him, but I never got to the actual experience. With the exception of a few wild gallops across the desert we were never alone. He rode as I did, without a thought to consequences.

About this time I was very much interested in feet, hoofs and paws. I felt over the extremities of every statue I saw. Even now I never pass a statue representing strength—a lion or a horse—without touching it. Several times I have felt all I could reach of the lions in Trafalgar Square. I have covered with my hands the entire anatomy of the two bronze lions outside the Hong-Kong and Shanghai Bank in Shanghai. Potty? Oh, no; just a peculiarly sensitive sense of touch, which even if blind, would give me pleasure in definite contours.

Can’t you hear the psychologists saying she has some sort of fetish. She has nothing of the sort. The psychologists must have a hidden reason for everything. My interest in feet and my pleasure in feeling the contours of statues, no doubt indicate that I have a secret wish to live with a negro, or to watch the mating of animals or any other desire equally ridiculous. I have often wondered what the psychologists would do without the word complex. That poor old word can carry more on its back than a camel.

Grandfather gave me some modelling clay, and I copied the feet of statues, human feet, the hoofs of the horses, Rex’s and the cat’s paws. I had given up drawing the buildings I saw and the plans of imaginary buildings.

Rex died during our second year in Egypt. I resented his death. I could see no sense in life if death was to be the end. I thought of God as a monster who perpetrated hideous jokes. I left off saying my prayers after Rex’s death.

When I was twelve I began seriously to take an interest in literature, especially French literature. I still prefer it to any other. The French have graceful, bendable minds, which can curve round anything. I read Anatole France’s “Penguin Island” seven or eight times until I was quite familiar with the Penguins. In fact, I made a little penguin out of black and white velvet which I called Anatole. I took Anatole to bed with me every night for some weeks.

Mr. Vanburgh gave me the best of his whimsical original mind during my studies—but along the lines I was going I had to travel alone. I had to think my way through—to get my own impressions. I studied English literature too. Trollope, Bunyan, Swift, the Brontës; then Hardy, Shaw, Wells, Bennett. Shakespeare I came to slowly because Mr. Vanburgh was always talking him up to me. I never liked Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot or Meredith.

I put all the authors away one day and decided to read nothing but poetry. I wanted to soak in the colour of it, for the poets belong with the painters and not with the authors. I read Villon, Blake, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Walt Whitman and Byron. Later I discovered Edgar Allan Poe and I read him for hours on end. I loved poetry then more than anything in the world. I tried to think of poetic words to describe everything I saw. What poetry would fittingly describe the desert, the sunset, the tombs. I was to know later that poetry needn’t describe anything, that the most helpful things must be said in prose, for poetry cannot be expected to turn her beauty to service. I had none of the so-called modern ideas about poetry. Every age produces its moderns. They are as old and as young as Time. While it lasts each group thinks it has the ultimate word. The only thing which makes literature different from the stringing together of words, which to-day is called writing, is the poetic ingredient. I am not saying that much of the writing of yesterday was better than the writing of to-day, but this feverish desire to be what is known as modern, this ridiculing of romance and sentiment, is only the striving to be different. A lot of the present clever writing is such tiresome bunkum! The wish to be sprightly overshadows everything. The poets, on the other hand, are a long way from being sprightly. They wallow in transcendental gush and rare erotic states, insisting that poetry cannot be explained. Rubbish! Poetry is as simple as the smile on a baby’s face and as universal. We find it in all sorts of situations. Why make such a mystery of it? It is quite true that much of what is now called poetry cannot be defined. But is it poetry any more than crooning is singing? It all comes from the wish to own something. Each generation wants its own stamp; something which makes it special and sets it apart from all previous generations. Each age must, willy nilly, do the modern thing. The poets themselves and certain lovers of poetry are trying to keep up this Hindu attitude of secrecy towards poetry. They want it to belong to the few initiates. Poetry is an emotion. Anyone, according to his emotional nature, can get the feel of it as he can get the feel of love and passion. In speaking of the modern writing I have nothing to say against stark naked prose. Often it exposes lovely flesh tones, graceful curves; in short, poetry. I object to the writing which is neither naked nor dressed but which aims at being so damnably clever.