Farewell to Priorsford

A Book by and about Anna Buchan (O. Douglas)

Preface

This book has been compiled at the request of many who wish to know more about Anna Buchan by those privileged to enjoy her friendship.

This commemorative volume is presented in the hope that it will give to all who enjoy Anna Buchan’s books a share of the fun, the courage and the inspiration she gave to all who knew her.

Anna Buchan of Priorsford

- A Biographical Introduction — A. G. Reekie

- Anna — Susan Tweedsmuir

- Olivia — Alice Fairfax-Lucy

- Author and Friend — Christine Orr

- A Peebles Player — William Crichton

Stories by Anna Buchan

- Introductory Note

- A Story for Young and Old:

- Broughton and Two Broughton Stories:

- Two Long Stories:

- The First Eight Chapters of a Novel:

Anna Buchan of Priorsford

A Biographical Introduction

A. G. Reekie

“There has been so much happiness and such great sorrow; but the sad bits are as precious as the happy bits, and they all help to make the pattern. On the whole, a gay pattern.”

— Ann and Her Mother

“What was Anna Buchan really like? I’ve read all her novels and her autobiography, but what sort of person was she really?”

Many readers of the books of “O. Douglas” have asked this question; some may have asked with slight apprehension being aware that successful novelists sometimes prove to be unhappy people quite different from their books. Pre-occupied with their work, some writers tend to be detached and indifferent citizens and companions. In the case of those few fortunate mortals whose days have overflowed with happiness as well as success—as Anna Buchan’s did—such gifts given so generously may spoil the recipients and make them self-centred, inconsiderate and lacking in sympathy.

Anna Buchan was without a trace of the occupational weaknesses of the famous novelist or the self-absorption of the very successful. In her personality and in her achievements, apart from her wide appeal as a writer, she attained to a distinction of character and an influence of exceptional quality. This makes difficulties for those who seek to portray her to others who did not know her personally. Anna Buchan was in fact one whose personal goodness was of such a quality that it made an unforgettable impression on all who met her. An entire community is ready to testify that her influence permeated the town in which she made her home, and which she used as a setting for many of her tales.

Priorsford is, of course, the bright attractive county town of Peebles. It can be said that by her life and example she turned Peebles into Priorsford. Peebles was a little kingdom where her influence was inescapable, and it was an influence that enriched all the civilising aspirations of the community.

It will help those unfamiliar with the inner nature of Scottish life and character to understand Anna Buchan better by recalling the richness—the peculiar Scottish richness—of her heritage.

Her people were Borderers for many generations. Border folk have a marked individuality. For centuries the people of the Border country were comparatively untouched by the main currents of national life. This developed an independence of judgment, a love of stories about themselves and a strong sense of community.

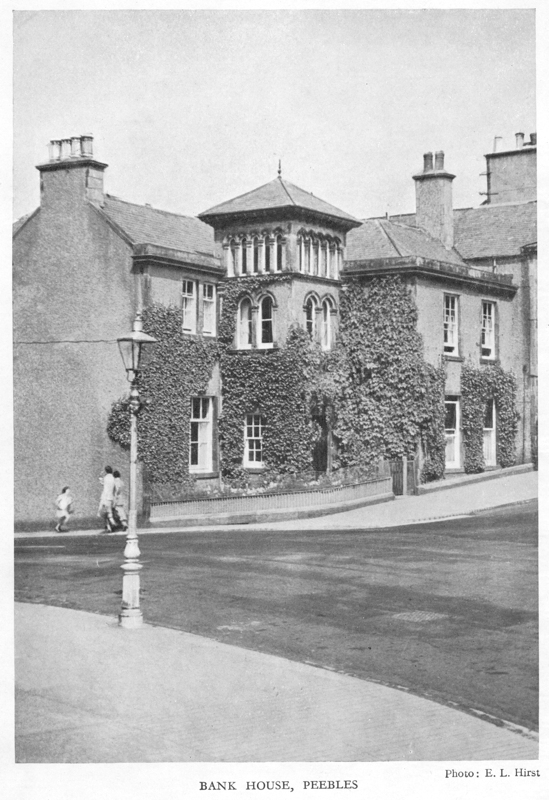

Anna Buchan’s paternal grandfather, whose brass plate inscribed Mr. Buchan, Writer, remains on the bright red door of the Bank House in Peebles High Street, was the legal and financial adviser to the prosperous sheep farmers whose flocks swarmed all over the hills of Tweedvale. Among the farmers was Anna’s maternal grandparent, John Masterton of Broughton Green.

To this strain in which Border character and prospering security were finely proportioned was added an upbringing in a Scottish manse. It is not quite accurate to describe a Scottish manse as the equivalent of an English vicarage. The traditions of the Scottish manse are not so closely linked with the ruling classes of the past. There was a much more stern view of human destiny in the Scottish clergyman’s home due to the Calvinistic doctrines which prevailed in Scotland for so long. If behaviour was strictly defined, it was because there was nothing more important than character. If life was held to be a solemn destiny, it cultivated personal expression of a high order. Other books besides the Bible were warmly cherished. Great minds as well as great hearts were reared in Scottish manses.

Anna Buchan was born in a Scottish manse. Her father, the Reverend John Buchan, was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland. The eldest son of the well-known Peebles lawyer, after completing his course at Edinburgh University, and prior to becoming an ordained minister with a church of his own, took charge of the Free Church at Broughton, fourteen miles further up the valley of Tweed from his home town, during the winter of 1873. Moody and Sankey, the American evangelists, were then in the capital. The young minister brought their hymns to Broughton, and he stirred the village with his earnest preaching and conscientious visitation.

Helen Masterton was only sixteen when the zealous young clergyman sought her hand. In the spring he was called to be minister of Knox Church, Perth, and before the year ended Helen Masterton became mistress of the Perth manse. The congregation gave a warm welcome to the girlish bride who had “put her hair up for the first time on her wedding morning. No congregation has ever welcomed a younger bride to its church and manse than this Border girl. A year later another John had appeared, and, soon after, the blissfully happy parents left Perth for Pathhead Free Church, near Kirkcaldy, in the kingdom of Fife.

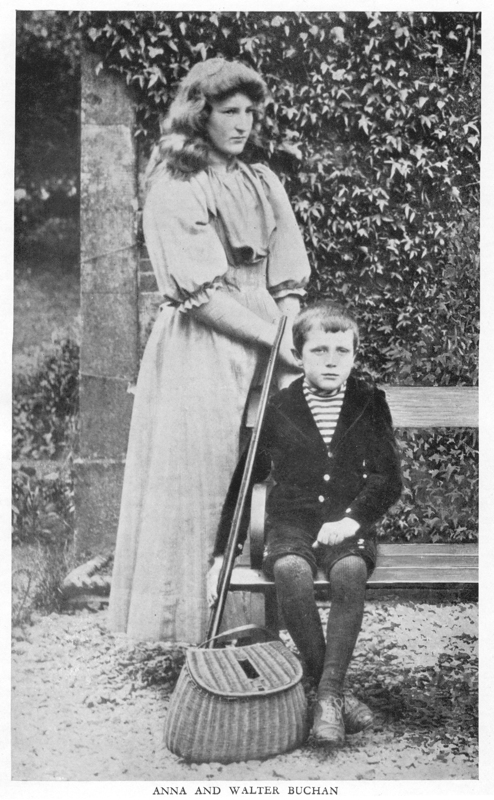

The Pathhead manse, the scene of Anna’s birth, was a substantial, roomy house with a large garden. One of the windows of the nursery, which Anna shared with William and Walter, who followed her, overlooked the garden and commanded a view of the broad waters of the Firth of Forth. The intermittent shafts of light from the beacon on Inchkeith was in Anna’s imagination the flickering gleams of a giant’s lantern.

A visitor to the manse in those days describes the young mother sitting in her low chair encouraging the children in their jokes and banter; and sometimes appealing for protection from them. Mr. Buchan would sit silently while young John expounded a bright new idea of his or listened to Anna reciting or asking a lively question. Life in a Free Church manse of those days had a moral austerity and a firm code of behaviour, but the children were allowed ample expression for their developing talents as well as their high spirits.

Brother John was the natural leader in the numerous adventures of the minister’s family. Pathhead was not a particularly romantic district, but John cast a glory over all of it for his sister and brothers. They went to the woods, to the docks at Kirkcaldy, to the little fishing places along the coast, and many exploits had their venue around the coal-pit. From the beginning John was destined to be Anna’s hero. John was born to lead, was infinite in resource and knew more than any other boy knew. Moreover, did he not have a scar on his head as a result of an accident which nearly killed him?

Children of the manse are notorious for the amount of mischief into which they fall. The Buchan family was not an exception. Their escapades were many and varied, and these were frequently recounted by members of the congregation in shocked tones mingled with admiration and repressed mirth. Some of those childhood pranks are re-told in the novels of Anna.

As a child Anna, was singled out for special mention. She was the worst behaved, but allowance must be made for hero-worship. Though she was a girl, she must not fail John. She made herself what used to be called a tomboy so that John would give her commissions as readily as he gave them to William and Walter. Anna had to establish that she could be trusted just as much as her younger brothers when deeds of daring were the order of the day.

Mischievous to the extent that they once set a woodpile ablaze at the coal-pit, their pranks were more than balanced by the nature of their home life. The Buchan children were drawn naturally into a devotion for literature and a regard for the great virtues their father proclaimed in his sermons and in his life. The children came to know the Bible and the Pilgrim’s Progress as endless stores of wonderful stories, and as source books for all kinds of games. John re-named the physical features of the whole district with names from Bunyan.

Mr. Buchan’s ministry in Pathhead was a fruitful one; he was noted for the power of his appeal to young people. He had talents greater than have been generally recognised. While at Pathhead he published a volume of verse entitled Tweedside Echoes and Moorland Musings, which indicated a natural talent for song. This and another volume of theological writings were, however, minor interests. His deep sense of vocation as a minister of the Gospel made him centre all his energies in his high calling.

To his own children he seemed a wonderful father. In a privately printed tribute to his memory Anna wrote of those Pathhead days:

“What a wonderful father he was! When he came to the nursery tea, fairies spoke out of the teapot, and the fearsome Red Etain of Ireland and cunning Whippitie Stourie joined hands with English Alice to make a Wonderland. He played like a boy, and knew well and loved the good land of ‘Make believe.’ On winter days how he shepherded his flock through the Dunnikier Woods to the pond, and bored holes and fitted skates on to five pairs of feet; then so patiently gave the staggering company their first lesson in the art of skating. In the evenings, with the red curtains drawn in the study, two on his knee and two on the rug at his feet, and ‘Mother’ sitting near, listening, and mending childish garments, he would read of Bruce and Wallace, of John Knox, and that lonely lady, Mary of Scotland, the Covenanters, and old, unhappy, far-off things; or he would get The Queen’s Wake and entrance his audience with the music of ‘Bonnie Kilmeny gaed up the glen,’ imbuing his children with something of his own passionate love for his native Scotland and for all the great kingdom of books.”

The parents’ deep love for Border country was soon shared by all the children. Each summer the children travelled to Broughton to live at their mother’s home, The Green.

Broughton lies in a beautiful hollow among high hills. Through it passes an ancient highway from Edinburgh to the south. The Green had been an inn. On wet days John would tell tales of highwaymen and other adventurers, who, the children were sure, had sojourned in the house, the rooms of which still bore their numbers from the hostelry days. All around was a countryside of Arcadian richness. No children ever had a finer playground. Its glories captured them completely. There were pools and streams to explore, trees and hills to climb, birds to watch, all the life and routine of a large sheep farm to share in, and the shepherds’ cottages to visit; all of an almost untouched pastoral world was theirs and its people, who could tell good stories about Walter Scott and James Hogg, were their friends.

This Border country with its many streams and valleys, each with its lore and songs of courage in battle or of love requited and otherwise, was a constant refreshment and source of inspiration. John was to find the setting here for his novel, John Burnet of Barns, and for Witchwood, one of his finest and his own favourite; Walter was to be its historian in his History of Peeblesshire, a county history and survey of exceptional merit; and in the novels of Anna there are many pictures of the uplands of Tweeddale.

Each September the children left Broughton for Pathhead with passionate regrets, soon forgotten on arriving at the manse. Then in 1888, the year Anna’s sister Violet was born, the John Knox Church in Glasgow, the oldest Free Church in the city, situated on the south bank of the Clyde, a church with a fine succession of scholarly preachers, called the Reverend John Buchan to be its minister.

Glasgow was an exciting prospect for the children. But the second city of the Empire with its agglomeration of people piled up in high tenements is an exacting sphere for a clergyman with such a deep sense of his pastoral duties as the Reverend John Buchan had.

Anna often talked of Glasgow. She maintained strong and affectionate ties with many of the families connected with the Knox Church long after she had left Glasgow. I knew Glasgow well, and I was not unfamiliar with its South Side. Anna enjoyed speaking of the cheerfulness, the friendliness and the generosity of the Glasgow folk. One day I expressed some wonderment as to how they survived their dismal housing accommodation and those dark streets into which the sun seldom shone. As this seemed to Anna to imply some sort of criticism, she was at once ready to defend.

“They have a spirit that rises above these dreadful disadvantages,” she declared with emphasis. Her father certainly had. Into that huge pool of strenuous, teeming energy and frightening poverty he bravely carried his message. At the cost of much tramping through city streets and climbing stairs, he ministered to the members of his scattered congregation.

The children approved of their new home in Crosshill at 34, Queen Mary Avenue. This large villa still preserved something of its former rural peacefulness, though only two miles from the centre of the city. To their father the garden was some compensation for the lost sight of the fields and woods of Pathhead. Little Violet, alone among his children shared with him his delight in flowers, though John wrote of the garden in The Scholar-Gypsies.

At Pathhead Mrs. Buchan had added to her knowledge of domestic management an understanding and a capacity for the many duties of a clergyman’s wife. In all the work of homemaking, family upbringing and the Church she was now wise and experienced. She, too, visited the congregation, especially the old and the sick to whom she always carried comfort and a gift.

Anna was sent to a small private school. Later, when William and Walter joined John at Hutchesons, Anna entered the corresponding school for girls. She did not shine at her studies as did her brothers. For the Buchan children schooling may be described as a minor episode. Without disrespect it could be said that the most important lessons Anna and her brothers learned were those taught at home. School games were less enthralling than those they devised themselves. Every corner was peopled with the creatures of their imagination, and every day crowded with glorious adventures. These first flutterings of the creative power that was to be manifest so richly in John, and so enchantingly in Anna, were not repressed. In the Calvinistic household of the Reverend John Buchan there was a reverence for the gift of imagination. The children grew up in a fellowship in which they were held together by the most powerful bonds. Their family circle was a magic circle; their home a secret order of delight and its shrines were religion and literature. To the Reverend John Buchan and his wife was given the knowledge of how to raise a family so that all the talent within it was allowed to grow and flourish.

By 1892 childhood days were drawing to a close. John was preparing for Glasgow University in the autumn when Anna was to go to school in Edinburgh. But in the summer of that year Violet, now five, was far from well. She was a frail flower. Her delicacy had endeared her to her sister and brothers. Violet made Anna limit her pursuits with the boys. The days of the wild games were over. Anna was ready to give up excursions with her brothers in order to take her sister out to the Queen’s Park nearby, and to look at the shop windows in Victoria Road. Violet was the first to demand a story from Anna, who began a tale of their future life together of which Violet never tired, and even Willie and Walter occasionally joined in listening to Anna’s domestic chronicle about babies and baking, and of how all their lives were to be lived in a place very like Broughton. But the frail flower faded early. On a bright June morning Violet died at Broughton, where she had been taken in the hope that she would revive there.

This was the first of the sharp sorrows the Buchan family were to suffer. To the Reverend John Buchan it was his deepest sorrow.

In Edinburgh Anna lived at the home of a retired clergyman and his wife while she attended a school managed by two French ladies. It was more suited to her natural aptitudes than Hutchesons. Dull studies had no place in its casual curriculum. In its English literature class Anna won her one and only scholarship prize. What Anna enjoyed was the opportunity of exploring the capital. Knowing so well the history of Scotland, the city was not a strange place to her. When she went for music lessons to a teacher in Queen Street she returned by way of Castle Street so that she could gaze at the window of No. 39 through which passers-by once saw the hand of Scott covering page after page.

Anna saw the gentility of the capital exemplified in a great-aunt, whose teas consisted of tiny pieces of faintly buttered bread set on large silver plates, scones as small as a coin, miniature cakes and extra large cups half filled with weak tea—a genteel tradition that has not yet wholly disappeared. Anna remembered the sumptuous high teas of Glasgow, and this increased her yearning to return home. When she learned of the advent of another brother, she pleaded to be allowed to do her studies in Glasgow and ultimately the parents agreed.

The new arrival, Alastair, was known first as Peter, then as the Mhor—Gaelic for “ the great one.” Anna loved and cherished him. Mother was absorbed increasingly in church work and public duties so Anna mothered her youngest brother and took her responsibilities seriously. The Mhor was a mine of sayings which have been preserved for us in several of the novels.

Formal education was continued at Queen Margaret College, while John, a comparatively inconspicuous student at Glasgow University, was writing essays, short stories and a short novel, Sir Quixote of the Moors. Anna, as befitted a daughter of the manse, joined in Sunday school teaching beside John, whose class of Gorbal wild youngsters appear in his Huntingtower. Anna also assisted at Band of Hope (temperance) meetings and collected for missionary enterprises. She also visited many homes of the congregation and extended her knowledge of Glasgow life and character.

This routine of meetings and work connected with the life of a city church may seem dull to the outsider, and one which a girl of Anna’s lively spirit might wish to escape at the earliest possible moment. But she had no wish to escape from such activities. To the last year of her life she attended and addressed such meetings. She never thought ordinary people were dull just because they were ordinary. Her very acute powers of observation gave her insight into the latent comedy and pathos of ordinary human nature. This fact was partly contributory to her success as a novelist.

Though John was busy “commencing authorship,” Anna’s ambitions lay in another direction. She wanted to be an actress!

In her case this was not the foolish fancy of a stage-struck girl. She had attended a recital at which a well-known Shakespearean actor and actress had presented scenes from Shakespeare. Anna thought, with reason, that she had qualifications for a stage career. But in those days daughters of the Scottish manse did not enter the auditorium of the theatre, much less appear on the stage. In an earlier and less circumspect age the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland had adjourned to attend a performance by Mrs. Siddons, but a more critical view of the theatre by the churches was prevalent in Anna’s youth. Anna could not and never wished to pit herself against the traditions of the manse. She found a happy outlet for her desire to act in reciting extracts from Barrie and ®ther Scottish writers at all kinds of gatherings. Later she appeared in amateur theatrical productions and for many years delighted large audiences all over Scotland with her lecture-recitals in which she revealed her talent for histrionics. She could present to the life almost any Glasgow type. All her life in conversation she never told a story carelessly, but gave it the tone and accent which were exactly right.

Many who have enjoyed her company have spoken of the pleasure they had in meeting her. Part of the secret of her power to make even a short conversation stimulating and refreshing lay in her gift, which she possessed to an unusual degree, of projecting a character or a phrase or a word so that its impact was felt.

One day I was with her when the mother of a soldier—an only son—came to her with the news that the lad had been wounded. To watch Anna comforting this distressed mother was a revelation not only of her deep understanding, but of a great gift for personal expression. Her sympathy rose to the level of an art. Her exact use of homely phrases, Border words, comforting words, was impressive. I watched the mother reviving as Anna’s words went home to her heart. When she left us I simply shook hands. Anna had said all that ought to have been said and said it superbly. There was lots of satisfaction for Anna in giving her recitations; she enjoyed the warm response of her audiences. But there were other excitements. John had gone to Oxford and almost overnight had secured a firm and lucrative position in publishing circles. He wrote more and more essays and articles while still a student at Brasenose College, but his Oxford career did not suffer. He won the Stanhope prize for an historical essay and the famous Newdigate prize for verse.

The Buchan family was a very closely-knit one. There was something of Scottish “clannishness” in it, but it was not marred by a lack of interest in others, which is sometimes a feature of such families, nor was John the sort for whom great success meant a slackening of family ties. Anna’s first visit to England was due to John’s wish that she and Mrs. Buchan should spend a week in Oxford. The road south was one that Anna was to take often. For one who in so many respects was Scottish to the core, she had a very deep affection for the traditional in English ways. The rolling English road, the inns, the little fields and cultivated landscapes never failed to delight her all her life, and she journeyed each year to Oxford and Stratford with unabated zest.

This first visit was memorable. John was President of the Oxford Union, a coveted undergraduate office held by so many famous men. Anna was twenty-one, but she had never been in a theatre. So her attendance at the Oxford University Dramatic Society’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was one of her unforgettable experiences. Anna knew and loved the play. Her knowledge of Shakespeare’s work was deep. Untroubled by the problems about Shakespeare that vex so many university professors, she was the Shakespeare lover in excelsis. She could quote from the bard with an enviable readiness on all occasions. That she did not always do so is an instance of her tact. She refrained from making an apt quotation to one who might not appreciate it. She shared her enthusiasms with those who understood her enthusiasms. She had a strong dislike of bores, and took pains never to be one herself.

The Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-on-Avon was not visited until after her father’s death. Its presentations yielded her one of her greatest joys. She became a regular Stratford pilgrim. Though she knew quite well all that could be said against Stratford, nothing ever caused her to lose her love of the place. Even in her last years she set out for Stratford with an eagerness that made one realise that Shakespeare was for her a source of never-ending delight. Her love of the Bard survived the long years, the many other interests of her life, her excursions into grandeur, the deep sorrows, and the weariness of the grim years of war. Her affection for the Stratford productions of her idol survived many changes—changes in the town, casts, stage techniques and even the change of theatre.

Anna’s deep and abiding interest in the theatre was not, of course, limited to Shakespearean plays. Every visit to London meant nights at the theatre. She travelled regularly from Peebles to Glasgow and to Edinburgh to see the trial runs of future London productions, as well as many repertory and amateur presentations. She was very nearly the perfect theatre-goer, but, reared as she was on Shakespeare’s profound sense of the dramatic and comic she was never deceived into accepting the third-rate for more than it was. She could give a shrewd analysis of a play and quickly perceive its flaws.

Sir James Barrie’s last play, The Boy David, was first produced in Edinburgh. Anna was present at that ill-omened first night. In a few words she described the strength and weakness of this Biblical play, and her prediction of its future course proved accurate. Her sense of theatre and her common-sense made her a just and reliable critic. Yet her primary reason for entering the theatre was not to criticise, but to give herself up to the make-believe of the theatre that the true inwardness of life might be unfolded.

Anna sought for this same revelation in her reading. She naturally read extensively. She knew all the modern writers. If she did not like some of them it was not because they were modern, but because they were inadequate. The film, the book and the play that could show only the sordid was distasteful to her, because it was so far from being the whole picture. She knew countless men and women in all walks of life, and she was persuaded that the true pathos and sublimity was not in the murky deeds of men but in the mystery of their invincible hopefulness and their persistent aspiration.

At the beginning of the century Glasgow’s cultural life was vigorous and stimulating. Anna was touched by the prevailing enthusiasms, and, in particular, she was impressed by youthful artists some of whom talked art to the exclusion of all else. Anna acquired a desire for darkened rooms and incense-burning. Only a little plain speaking was necessary for Anna to recover her excellent sense of proportion.

Anna did not, however, forget that she had once fallen into such a spell. Her deep understanding of youthful ambition grew out of her own youth in which she travelled along a set path. She showed how her own willing acceptance of the road set before her had immeasurably enriched her life. Her counsel to the young had special value. She did not forget that it is natural for youth to be extravagant in desires, enthusiasm and expression. She dealt tenderly with the dreams of the young, and, though her own youthful extravagances were mild and short-lived, she well remembered them and her humorous recounting of them made youth listen, as they did, to what she advised them.

The confines of the manse were breaking down. The Buchan family were beginning their travels which were to take most members of it to the far places. In 1900, when Mrs. Buchan had a serious illness, Anna had her first experience of housekeeping. In the summer, John took Anna to Switzerland as a reward. The following year John ventured upon his first essay in practical statesmanship by going out to South Africa as one of the notable band of assistants to Lord Milner, the British High Commissioner. At the end of the year the Reverend John Buchan accompanied by Mrs. Buchan and the Mhor, went to the same country to fulfil a temporary ministry of several months. This trip was very happy and successful, and, while her parents were from home, Anna spent most of the time at Peebles with Uncle William and her two aunts.

In 1906, the death of this uncle at Bank House was determinative of so much for Anna. The old family business in law and banking was without a head. William was in India advancing a successful career in the Indian Civil Service. John was back in London, and, though he was practising not very happily at the Bar, his career was obviously set on a very much larger scale. Walter, preparing for the Scots Bar, had to take over, though lacking in experience. Yet such was his ability—which he enjoys concealing—that he quickly established himself as banker and lawyer as well as Clerk to the Town Council, and as Procurator-Fiscal responsible for the presentation of charges at the local Sheriff Court.

As the two aunts, who had managed the Bank House, had resolved to retire to the Channel Islands, Anna became mistress of the family home, and from this time forth it was to be her home and Peebles her personal kingdom.

Peebles is one of the most attractive small towns in Scotland. A population of 6,000 live a well-developed communal life and take pride in the town’s history and charm. Its size preserves it from the depressing anonymity of city life, and yet prevents the excessive curiosity of village existence. Set in the heart of beautiful pastoral country on the banks of Tweed, few homes in the town are without a view of the surrounding wooded hills.

The town is divided into well-defined sections: the Old Town with modern extensions, the Northgate, the Eastgate and the prosperous suburb on the south bank of Tweed. The Bank House stands at the centre on which these four districts converge. Situated at the west end of the bright and broad High Street, which is faintly reminiscent of an English scene, the House is close to the highway. It is much more modern in appearance than one would expect in a building over a century old. The main entrance and vestibule is actually part of a tower which enhances its air of quiet distinction.

At street level are the public rooms including the sitting-room with its restful atmosphere, many books and family portraits and its large bay windows which look out on the garden sloping down to Eddleston Water just before this river pours into Tweed. Downstairs, which is at garden level, are the kitchen quarters, and upstairs are the bedrooms which either overlook the street or the garden. This was the home Anna managed for forty years in the course of which it became the centre of so much that was fine and admirable in the community and in which she entertained so generously. Here, the great ones came and the humble ones too, and all left refreshed and happy.

The departure from Glasgow was the end of a long phase that had been formative and enriching. The circle of her acquaintances was to widen as the years brought success and fame. In Glasgow the circle had been more or less limited to those open to a daughter of the manse. Most of her youthful years had been spent within the circumference of church life and work. Her errands in the Gorbals making sick calls or collecting for missionary causes, had given her insight into the life of mean streets, and her visits in the suburbs of Glasgow an understanding of the hopes and fears and the social environment of the city’s middle classes.

All her memories of these people—their pathos, their shining courage, their wit and humour—were safely stored away. Years were to pass before her experience of the warm common humanity of Glasgow life was to be given the appealing and entertaining presentation she gave it in her novels. For there was as yet no sign of “O. Douglas”. At twenty-eight Anna was fully occupied in the management of Bank House and acting as hostess to her brother. Many calls of a civic character claimed her and, though no longer in a central position in a church as the minister’s daughter, she was almost as busy as she had been in Glasgow in the activities of the church.

The same year as Anna came to Peebles, John intimated his impending engagement to Miss Susan Charlotte Grosvenor. To such a family as the Buchans this announcement was momentous and caused, not unnaturally, some apprehension. Miss Grosvenor was an English aristocrat with a most distinguished lineage; she was a direct descendant of the Duke of Wellington. Her background was full of all that is fine in English ways of living, and in contrast to the Border heritage of the Buchans. To Anna, John had been a glorious companion, wise counsellor and hero. Such a marriage as John hoped for must have seemed the curtailment of a very precious relationship, and the beginning of a gulf which would grow inevitably wider with the years. But the Buchan luck and love held. Susan Grosvenor, beautiful in person, brilliant in intelligence, enriched immensely the life and work of John Buchan, and the life of his brothers and liis sister by a friendship of deep charm and abiding strength; a friendship, which Anna reckoned as one of the great blessings of her life, and for which she so often expressed her thankfulness.

Anna and Susan shared so much happiness together. They also shared hard sorrows. When the shadows at last lengthened for Anna, Susan’s lovely companionship gave to the last a warm and comforting glow.

At the wedding of John and Susan in St. George’s, Hanover Square, London, in 1907, Anna was a bridesmaid. The Reverend John Buchan, normally reserved in manner, was happy and gay. He kissed his beautiful daughter-in-law and went to Paris for a holiday.

All the brothers vied with each other in their devotion to their sister. Anna was precious to each one of them. Willie in India thought the change in the balance of their family existence caused by John’s marriage was an excellent junction to insist on Anna visiting him.

The months Anna spent in India gave her a powerful impetus to write, though when she came back to Peebles there was little time for putting pen to paper. Anna felt no compulsion to forego any of her numerous activities so that she could concentrate on writing. Domestic and family affairs were as engrossing as ever. Moreover, the long spell of freedom from severe anxieties was ending to be followed by years of strain and sorrow.

The family felt that their father should retire from his heavy labours in Glasgow. The Reverend John Buchan was sixty-two, and he was growing less able for his strenuous pastoral duties. Much persuasion was necessary before he finally agreed to leave the Knox Church. At last the Reverend John Buchan retired, and came to reside in a house opposite Bank House on the other side of the river. A pleasant retirement was planned with occasional preaching engagements and work on a book about the poets of Peeblesshire. But the ageing minister had a heart attack while on holiday in London. On returning to Peebles, he had to accept restrictions on all his activities. His contented spirit and his joy in living among the hills of home helped him to recover a fair degree of health. Then Mrs. Buchan was stricken with a menacing fever due to a mysterious disorder of the blood, later diagnosed as pernicious anemia. Doctors and specialists were puzzled—a fact which furthered Mrs. Buchan’s scepticism about their powers.

As the illness of Mrs. Buchan was protracted, it was decided to give up the house on the South side, and so the Reverend John with his now invalid wife returned to the home of his birth, where Anna and Walter shared in the exacting burden of caring for their very sick mother, and guarding their father, as far as possible, from’ the tension and worry caused by Mrs. Buchan’s mysterious and persistent malady.

Anna spent many nights sitting up with her mother. Writing proved one way of keeping awake. Anna forgot for awhile the anxieties of the night in recollecting the happy carefree days of her Indian tour.

Mrs. Buchan’s fever continued to rise and fall alarmingly until she was taken to London for treatment by Sir Almroth Wright, the famous physician and bacteriologist.

There were many anxious hours before the treatment proved successful. After three months Anna brought her mother and father safely back to Bank House in the summer. John and Susan and their two children spent part of the summer at Harehope in the Meldon Hills only a few miles north of Peebles. The prospects of a more cheerful winter were brighter, but, before winter came, the Reverend John Buchan passed to his rest.

Anna now felt that she had a story she must write. It was a biographical sketch of her father to preface a privately printed volume of some of her father’s theological essays and sermons with a selection of his poems. What she wrote was deeply felt, and it shows the profound effect his example had upon Anna. Though her love for her mother was obvious to all, her father’s teaching had reached the deep heart’s core. The intense evangelical faith of the Reverend John Buchan had quickened no one more than his own daughter. She was his best disciple; for the inspiration of her life she drew deeply from his saintly example. John wrote of his father:

“He loved all changes that the seasons bring;

Enough for him the homely natural joys;

The wayside flower, the heath-clad mountain rift,

The ferny woodland, were his favoured choice.

Each year with grateful heart he hailed the gift

The princely gift of Spring.

Not as the thankless world that takes God’s boon

With blinded soul on trivial cares intent,

To him heaven shone in every summer noon,

And every morning was a sacrament.”

To Anna her father was another Mr. Standfast, and only she could have told all that he counted for in everv day of her life.

Anna was glad she could find some measure of forgetfulness in writing. Before the coming of spring, she had completed the story of her visit to India. Messrs. Hodder and Stoughton undertook to pubfish the book under the title Olivia in India. It was a special pleasure to Anna that this famous firm became her publishers. One reason being that in those days they were perhaps the publishers best known to clergymen, and she had seen many of their books in her father’s study. But her modesty kept her own name off the title page. By this time John was the author of over a dozen successful books; he had also made a reputation as a publisher through his directorate of Thomas Nelsons, and he was prospective Unionist candidate for Peebles and Selkirk. To Anna, John was doing what he had always done—he was doing most things better than most could. She did not wish the name of Buchan to be associated with her first novel, which she considered of much less consequence than any of her brother’s, even though it would have given it favourable publicity. So the pseudonym that was to become so well known, “O. Douglas”, was chosen.

Willie, of course, was especially interested in his sister’s book about her stay with him in India. He was due home on leave. Anna looked forward to showing him the proofs of her novel, but by the time these were available Willie Buchan was a stricken man. He came home tired but in good spirits. Soon after a mysterious malady affected him. Treatment was unavailing. Each day he grew weaker. Willie, the most handsome of the Buchans, the able administrator, the jolly fellow with the monocle, the promising writer, the very dear brother, was doomed.

The distress of the family was acute. John travelled constantly from London to Glasgow where Willie was in a nursing home. Anna took to him the proofs of Olivia in India. Willie, in severe pain, found a whole day’s forgetfulness in reading them.

William Buchan was a gallant gentleman. He met a cruel fate without complaint, and he left an indelible memory of a gay and courageous end.

His death shocked the family. The Buchan luck so many referred to, sometimes with a little envy, did not preserve the family from tragic loss. If their successes were exceptional, so were their sorrows in severity.

Anna and her mother could not conceal their grief. The winter was long and hard. Alastair, fortunately, had his classes at Glasgow University. Walter planned all kinds of quiet diversions.

When spring came, Anna tasted the sweets of authorship. Olivia in India was published. The novel was in the form of a traveller’s letters to home, and it set the tone and character of subsequent books. Her novels are mostly family chronicles. Part of the reader’s pleasure in them is the feeling of perusing a long letter from an old friend. The enormous sale of her novels was to some extent due to Anna’s marked talent for establishing a friendly relationship with her readers. Her talent in the genre was unsurpassed, and her first essay received a very encouraging reception.

James Douglas, then writing for the London Evening Star, wielded considerable influence on the sale of books he reviewed. His praise of a book could create a big demand for it; his condemnation had often the same result. Anna’s book delighted Douglas—an appropriate circumstance—and he devoted a whole column to his review of it. He described Olivia as “a happy book”.

Happy books are scarce. It is not given to many among the multitudes of all kinds of writers to produce a happy book. Though usually characterised as light literature, the writing of such a book demands special gifts as a human being as well as the essential talents of the writer. Anna’s books were happy books, but they were not made so by the avoidance of the harsh realities of existence. The world into which Anna took her readers was not the enchanted world of the fairy tale and happy endings at all costs. There is sorrow and sadness, sickness and heartache, and many a glimpse of the unfortunate in her novels. The shadows are there because she knew so well the grief and the burden of existence. The happiness in her books is secured, despite the misfortunes, because she cherished every gleam in the dark, every joke in the gloom, every comfort in the struggle. She held fast to faith in the ultimate decency of things. She believed much more than that; much more maybe than many of her readers might be able to accept. But the glow of these happy books indubitably sprang from their author’s deep and passionate belief in her father’s interpretation of life.

So it was natural that her second book would be about her father. She began to write it at the beginning of World War I, and before it was finished another break was made in the family circle. Alastair, the little fellow who appears in several of the novels with his quaint sayings, odd exploits and comic escapades, had become a Lieutenant in the Royal Scots Fusiliers. He had been much in war, had been wounded and had returned to the slaughter. On the 9th April, 1917, he fell in battle into which he had led his men with “words of comfort and encouragement”.

The novel about her father and Glasgow life often lay neglected. Anna was engaged in many kinds of war work, which included the entertaining of soldiers in the large military hospital the Peebles Hydro had become.

The Setons was the title finally chosen for the second novel, which, like the first story, was largely drawn from life with only a few alterations. It was a transcript of the life Anna had known so well, and which Glasgow folk at once recognise as authentic. The Setons was an immediate success, and letters began to pour in upon the author.

Though John had always been encouraging, Anna’s writing had not been treated as a matter of supreme importance. The Buchans took a certain degree of authorship for granted in their family. Willie had written, like his brother John, for Blackwood’s Magazine; Walter, despite his many civic, legal and financial activities, had published a monograph on his sister-in-law’s ancestor, the Duke of Wellington, the same year as Olivia had appeared.

After the publication of The Setons, it was clear that Anna’s novel writing should not be considered a mere pastime. For the next ten years she wrote with more regularity, and the novels of this period made her known throughout the land and the Commonwealth. She moved into the select circle of writers whose books are certain to run into many editions.

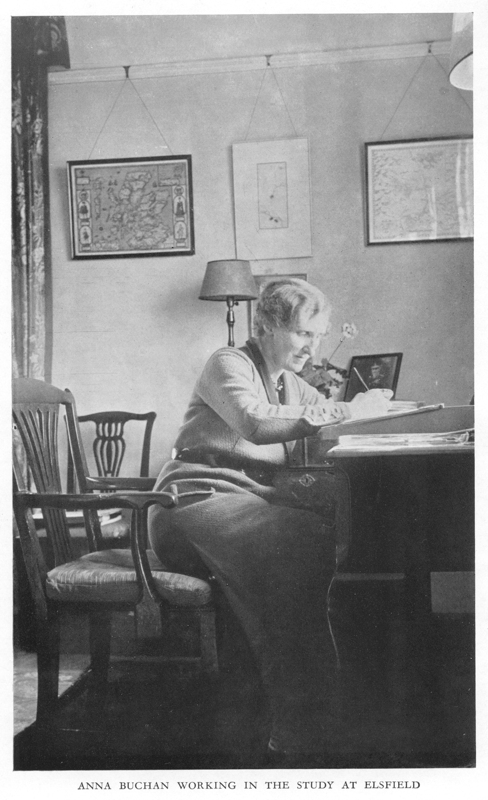

With each book the letters from admirers mounted higher and higher. Most authors in a similar position content themselves with formal acknowledgment. Such a reply was impossible for Anna. She refused to have a secretary to handle the large post bag that came daily to Bank House, and she refused to use a typewriter. She wrote in her own hand a friendly note of thanks to every letter of appreciation she received.

This burden and the increasing calls for her appearance at public functions throughout Scotland necessitated some change in the ordering of her daily life. Blessed as she always was with the help of a most efficient and devoted domestic staff, she nevertheless remained responsible for certain domestic duties. These tasks the essential shopping and constant entertaining, left almost no time for writing. So she arose at five o’clock every morning for her bath, then gave the next three hours up to the chores she had to do, so that part of the forenoon could be free for desk work. A strong constitution helped her to maintain this Spartan habit. I have seen guests gasp when she chose to reveal it to them.

Other hours for writing were also possible when the circle of three—Mrs. Buchan, Walter and Anna—were alone in Bank House. Writing was also possible when she stayed at Broughton in the summer, and at Elsfield Manor where John and Susan Buchan with their four children lived after 1920.

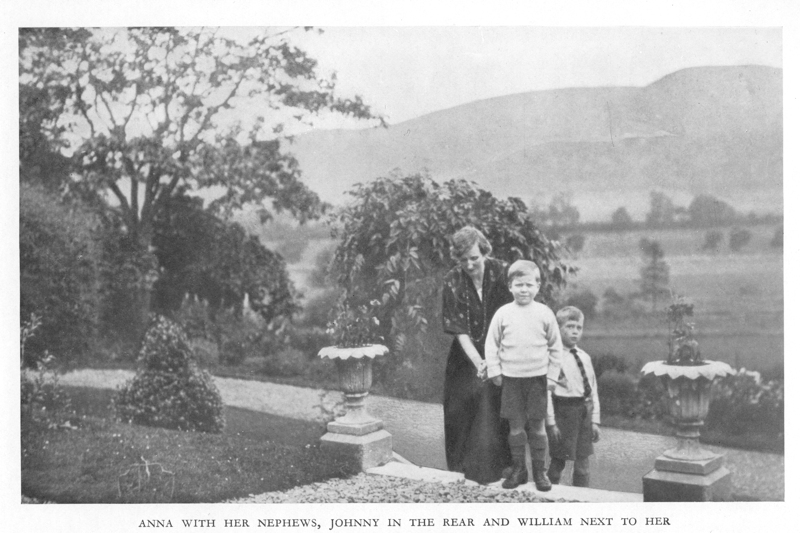

Anna’s visits to Elsfield in the spring, and the summer visits of her brother and sister-in-law with the children to Scotland, were among the happiest features of the 1920’s. Life had become more settled and serene, and, though the actual writing of a novel was not a joyful task to Anna, she was happy in the steady flow of her tales, which a very large public clamoured to buy.

Peebles was increasingly proud of the Buchan family. John was held in high honour everywhere. Walter was the much respected Clerk of the town, and his counsel was sought by all. Mrs. Buchan was a most familiar figure. She was everywhere where a kind word, a pot of preserves or a cake could do good. She and Anna were a partnership in good deeds unostentatiously performed. The character of these generous acts is known, but not their number. Mrs. Buchan’s visits to many a home was a benediction.

Though she now gave more time to her writing, Anna did not withdraw herself from the community she loved. She was to be seen most days in the High Street and elsewhere spending an hour on shopping, except when she was fulfilling one of the countless engagements, which took her to every part of Scotland. Her mother invariably accompanied her on these journeys to open a Bazaar, a Sale of Work or a Garden Fête. The task of the lady or gentleman, who has the honour of declaring such functions open, calls for a variety of gifts if it is to be really well done. The speech to be a success must be short and apt; it must please the audience, and must encourage the people to buy what the surrounding stalls have to offer.

On such occasions, which have daunted many an experienced speaker, Anna was excellent. The first time I heard her speak was at a Garden Fête and, though I judge myself a somewhat blasé listener to such speeches, Anna’s expert approach made me forget the formalities. She was at once on good terms with her audience. She did so through her gift of being able to speak naturally to a large audience as if it were a gathering of two or three friends. Two amusing stories cleverly spaced and timed in delivery, a clear and sympathetic understanding of the good cause for which the Fête was held, an encouraging word to the workers and a climax which went right home made, what so often is a trying sort of formality, a very pleasing and stimulating ten minutes.

The girl who had once wanted to be an actress was completely at home on a platform. Though she appeared so cool and calm and spoke so naturally, Anna never lost an innate modesty; there was always about her the faint flutter of a shyness, which character and will-power had disciplined.

Anna could enliven the dullest and most formal occasion by her gift of projecting her own zest and fun from a platform to an audience. Speeches moving the adoption of annual reports of charitable institutions come near to being the nadir of all speech-making. Even in this class Anna was never dull. An instance of her success in such a task was a speech she made when moving the adoption of the annual report of the Peebles Association of the Queen’s Nurses.

Beginning by contrasting the bad news in the newspapers with the good news of their Association, Anna described how her mother had collected in Fife in 1887 for the fund to form the Nurses’ Association as a gift to Queen Victoria. An old lady, whom her mother had called upon, asked: “Dae ye no think it wad be mair like the thing if the Queen gave me a present?” Then she gave a short graphic picture of pre-nursing association days, and quickly passed to an occasion when she had to prepare a poultice which, however, leaked. Then she said a few words about those who worked earnestly for the Association, and finally she praised the nurses, and told of an old man she knew who lived alone and required a nurse. He was strongly opposed to being nursed. “To think,” he said, “I’ve lived till I am eighty, and noo I’m gaun to be overpowered by a woman.” But, Anna concluded, he too lived to bless the nurses.

This speech is typical. Little wonder she was so much in demand. For years Anna willingly faced the fatigue and discomforts of constant travelling to make her brief appearance and effective speech and, though her mother knew well how reliable her daughter was, she frequently expressed concern over the speech she was about to make. It was Mrs. Buchan’s way of encouraging Anna to be at her best, but she almost always was. Though sometimes very tired, her vitality was exceptional. Her health never gave rise to anxieties. At home there were occasional remonstrances about the time and energy she spent in letter writing and speech-making, but Anna did not spare herself, and through the years never failed to answer a letter or keep an engagement she had contracted.

The circle of friends and acquaintances was constantly widening. John had been offered a choice of seats in the House of Commons, but his health was affected by a duodenal conditon, which was often painful; because of it he had undergone a major operation and several enforced spells of rest. In 1927, however, he entered Parliament as a representative for the Scottish Universities, being elected by a very large majority. His fame as a writer was widespread, and his counsel was sought in high places. Many people from all walks of life claimed his friendship. At his home at Elsfield he entertained some of the most famous people of the time, but other folk were equally welcome, and many a young man and woman found there a determinative influence on their subsequent careers.

Yet the family ties were as strong as ever, and Anna had frequent opportunity of meeting the famous and the celebrated.

Anna’s interests, however, did not centre in the life of high places, though she greatly enjoyed her occasional encounters with the great. She read much, but it would be inaccurate to describe her main interests as intellectual. Modern scientific and philosophic thought had little interest for her. Theological arguments had no appeal. She was fond of the old songs of her native land, but symphonic music had a soporific effect on her as theatre-going had on John.

She had an intense appreciation of other people’s gifts and achievements. She spoke as if everyone else’s work was much more important and much more interesting than her own. She delighted in encouraging others to talk, and it was always difficult to persuade her to speak about her writing. This was not an affectation; it was the ingrained politeness of the daughter of the manse; it was second nature for her to take a genuine interest in people. People fascinated her; she had a kindly curiosity about what people were doing and thinking.

Professor T. H. Bryce, a former Professor of Anatomy in Glasgow University, and a cousin of Lord Bryce who wrote The American Commonwealth, retired to Peebles. The death of his wife left him an ailing and somewhat lonely man. Anna visited him and persuaded others to do so. One day I told Anna I had spent the previous afternoon with the Professor.

“And what did you do?” Anna asked at once.

“Well, he felt able for a little stroll, so we went to the cemetery, and we sat there talking about immortality,” I replied.

“What a very Scottish thing to do!” Anna exclaimed. Then she added: “I hope your conclusions were sound.”

I said our conclusions would not have dismayed her.

She smiled and nodded. It was a slight incident, but it pleased her, and it was the kind of incident she could so well embellish in a novel.

Anna was very selective in her listening to the radio. She preferred to spend the evening reading when she was alone. She enjoyed most talking about books and plays. I cannot recall her ever making a harsh judgment. Unkindness was contrary to her code. That does not mean her opinions lacked sharpness; her opinions were sometimes very short and pungent. With her gifts of expression she could give a sentence a wealth of meaning.

A novel by a writer we both knew had proved disappointing. I asked Anna what she thought of it. She drew herself up.

“What dreary people!” she said. It was all she needed to say. The way she lengthened the word “dreary” was at once comic and devastating.

On political matters she voiced emphatic views, but she had no fondness for long political discussions on social occasions. There are only a few political judgments in her autobiography, Unforgettable, Unforgotten, but they are emphatic. Occasionally, she was persuaded to address Unionist gatherings, and in one hotly-contested election in a Parliamentary constituency, a striking speech she made to a very large audience swayed the issue in favour of the candidate for whom she appealed.

Anna had an extraordinary patience—as her mother had—with all sorts of people. Again like her mother, she was very kind to bores. But the pompous and complaining were exceptions. The pompous tended to make her laugh, and she thought very few persons were justified in being chronically woeful.

As John’s fame continued to grow so, in its own way, did Anna’s. Novels now came from her pen with regularity. Penny Plain, Ann and Her Mother, Pink Sugar, The Proper Place, and Eliza for Common—all received a rapturous welcome in the empire of “O. Douglas” enthusiasts.

Ann and Her Mother told the story of Mrs. Buchan. There is almost no attempt to disguise its true character. Though it pictures a world that has almost vanished, the years and the changes have not reduced its appeal. It contains several moving passages as well as vivid cameos and rich comedy. It gives flashes of the emotional power Anna held in reserve. Had she chosen to lead a more secluded life, she might have written novels on a bigger scale. Yet it is doubtful if the books she might have written would have had as an enduring life as the ones she did. Though her works were outside the fashionable trends of intellectual fiction, her accurately drawn portraits of Scottish character will have an interest and a charm for future generations. Already there arises a new generation, which eagerly absorbs the gentle but authentic tales of “O. Douglas”.

Penny Plain is the first of her stories set in Priorsford. Peebles was stirred to find its familiar features and some of its personalities in a very popular novel. The town reacted to the distinction Anna gave it by using it as a setting; there was a desire to enhance the charm and character of the place she skilfully presented in her novels. Thus it became more and more the “O. Douglas” town. For long a popular resort—even in pre-slogan days “Peebles for Pleasure” had a universal circulation—more and more were drawn to visit the town whose inhabitants pointed out Bank blouse with pride. More and more people rang the bell of the bright red door, and were given a gracious welcome.

Anna entertained on a very generous scale. She gave innumerable luncheon parties, and at afternoon tea guests of all types were to be met.

One afternoon one might find the Commander, a retired naval expert with a doctorate in science, who delights in making provocative remarks in a most bland manner. There is a quiet, modest lady, also a novelist, whose gifts Anna extols to all her guests. The thin, nervous lady is the one who played the organ at the meeting from which Anna has brought her, along with a clergyman’s widow, who is one of Anna’s most trusted lieutenants in good works. There is also the minister who spoke at the meeting and his wife is there too. One of Anna’s nephews, who is staying for a few days at Bank House, is also there. And Walter leaves his adjoining office for twenty minutes to join the group round the table. It is an animated group. No one is neglected. There are no pauses in the talk, and there is a lot of laughter. Everyone has a piece of Anna’s own gingerbread which she made with beer.

Anna was a natural hostess. Her own enjoyment in entertaining was obvious. People meeting her for the first time were surprised to find that they did most of the talking. Anna was a most sympathetic and encouraging listener. She had the power of concentrating utterly on what she was being told. This concentration may explain the ease with which she remembered little details about her friends and acquaintances; she could quote remarks from past conversations, which was often pleasing and sometimes startling. Very Little escaped her. As her mother observed, “Anna misses nothing.”

Every day was full. Anna served on many committees in the town and county. Peebles has a well-developed interest in music and drama, which Anna did much to encourage. Fond of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, she was President of the Peebles Philharmonic Society, which produced one of the operas every year. Anna was one of the Peebles Players, a successful amateur group, and she appeared with them in several productions and in performances at national dramatic festivals.

1932 was the last of the comparatively quiet and serene years, though this centenary year of Sir Walter Scott was exciting enough for a family who idolised the great wizard. John’s contribution was the biography Sir Walter Scott which G. M. Trevelyan has described as “the best one-volumed biography in the English language.” He also wrote a play for the Centenary celebrations at Peebles in which he played the part of Scott. He also wrote a play, The Maid, in which Anna appeared.

There were other happy occasions. Elsfield, London, Broughton and Peebles were the centres of most of them. A larger world, however, was now looming. John was about to enter a new life of service of the highest order. The prelude was John’s appointment as the Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. This office is unique in the United Kingdom. The Lord High Commissioner is the representative of the King; he lives in the Palace of Holyrood House, and he receives all the courtesies and ceremonial accorded only to Royalty; he addresses the General Assembly from the Throne Gallery of the historic Assembly Hall on the Mound of Edinburgh, and he fulfils a heavy programme of engagements during the ten days of the tenure of his office. Generally, this unique position has been held by a Scottish peer, and sometimes by a member of the Royal family. John Buchan was the first son of the Manse to hold the office, and his appointment was universally acclaimed.

The General Assembly brings ministers and elders from every part of Scotland into the Capital. Though a religious court, its debates touch upon almost every aspect of the life of the Scottish people. John Buchan spoke to it with a complete understanding of its place in the nation’s life, and from personal knowledge of the significance of the Church in the life of the people. He and his gracious lady made the occasion memorable. And it was so for Anna and her mother. All Anna’s books, as well as John’s, were to be found in Scottish manses so her presence in the Throne Gallery with her mother gave an added thrill to John’s Commissionership. Every day they were surrounded by people clamouring to meet them. For Anna’s mother this was probably the happiest time of her long widowhood. To the excitement of appearances at the Assembly and various social occasions, they had the pleasure of residing at the Palace of Holyrood House with elaborate ceremonies, the official dinners and the huge party in the gardens below Arthur’s Seat. All this exciting happiness was theirs again for a second time when John was appointed Lord High Commissioner the following year.

John was staying at Bank House for a few days in the spring of 1935, when he was summoned to Buckingham Palace. A few days later his appointment as Governor-General of Canada was announced, and he became the first Lord Tweedsmuir, taking his title from the tiny village close to the source of the river he loved. He threw himself, despite constant pain, with zeal and imagination into his high office. The people of Canada responded to the distinctive way he fulfilled his many duties. He helped Canada towards self-realisation.

Family ties were stronger than ever, and, in his first year as Governor-General, John was eager for his mother, sister and brother to stay at Government House in Ottawa. Anna had taken her mother on countless journeys, but this was the longest. At the age of seventy-nine Mrs. Buchan crossed the Atlantic with Anna.

It was a very happy visit, and they made more new friends. So the following year—the year of the Coronation of Their Majesties King George VI and Queen Elizabeth—Bank House extended hospitality to many Canadians.

But before the year was out Mrs. Buchan grew tired, and, on the last day of her long life, Anna saw on her mother’s face a look of utter content.

Her passing was lamented. Everyone missed the remarkable little lady who had been so kind to all. For Anna it was a very big breach. Her mother had occupied a large place in her life, and for many years she had been her constant companion. Some years later when Anna began to write her reminiscences, she talked frankly to me about the difficulties of writing autobiography. Then she confessed: “When I start to write, memories of my mother crowd in upon me. These are the memories that are uppermost, and I expect they always shall be.”

Walter and Anna were now alone in Bank House. The bond between them had always been strong. Now it was firmer and finer than ever.

I have postponed comment on a question that usually follows the question with which we began. The second question is “Why did Anna Buchan never marry?”

It is a natural question perhaps to ask about one so attractive as Anna was. But she was not a believer in the prevailing literary fashion that insists all must be told. We must respect her reserve. We must remember that every life has a private agony. It is improbable that Anna’s life was an exception. Perhaps some words of Nicole in The Proper Place were written out of her experience. Whatever heartache Anna knew from whatever cause, she did not ever fail to show the shining morning face, and she used her gift for fantasy and friendship to find a way to joy and peace. If there had ever been a sore wound, it had healed so well that none could detect the faintest scar.

The flow of novels continued though the interval between them lengthened slightly. The Day of Small Things, a sequel to Penny Plain; Priorsford, a sequel to The Proper Place; Taken by the Hand and Jane’s Parlour received a rapturous reception from her readers spread throughout the English-speaking world, and each book increased the correspondence their author had to tackle daily. This correspondence became a heavy burden, but Anna still refused to seek relief from it. There is no doubt whatever that this steady stream of friendly letters from her pen gave a great deal of pleasure and happiness to the recipients, but as the pile of incoming letters mounted, the effort of coping with them was a constant drain of time and energy. Appeals to Anna to reduce this labour was unavailing. The only concession she agreed to make was to accept Walter’s gift of a room he had prepared for her in a building opposite Bank House. Here, overlooking Tweed, Anna was able to write with more freedom from the ever increasing interruptions.

Anna and Walter returned to Canada in July of the fateful year of 1939, undeterred by the growing rumbles of the second World War. This visit gave the Buchan family the opportunity of spending the last few weeks of peace together, and they were the last days Anna and Walter were to enjoy with John. Anna and her brother returned to Peebles in time to hear the Prime Minister’s broadcast message that war had begun.

War brought large numbers of evacuees to Peebles which was a so-called safe area. Soldiers of the British and Polish armies thronged the streets of the little Border town, and crowded into its dwellings. Bank House entertained many of these visitors. Later, when the Canadian soldiers arrived, many spent their leave in visiting Peebles to see the ancestral home of their Governor-General.

That harsh winter, with all the uncertainties and uneasiness of the “phoney war” period, brought the hardest blow of all to Lady Tweedsmuir in Ottawa and Anna and Walter in Peebles. John Buchan’s amazing life, so rich in lasting achievement despite the adversity of pain, came to its end. On Sunday, 11th February, 1940, Anna’s “playmate, comrade and counsellor” departed this life.

Anna had a book The House that is Our Own to finish. It was to be the last of her published novels. The writing of it sustained her through sessions of grief.

Though the war gathered momentum, Anna and Walter still continued their journeys south. Anna saw for herself the ravages of the blitz, and she learned at first hand what it meant to suffer nights of bombardment. She continued to fulfil public engagements, and she served the Red Cross and other movements to help the cause of country. She ministered to those to whom war brought grievous loss. She was quick with her sympathy and her practical help. When a Peebles lad, a rear gunner in a bomber plane, suffered shocking injuries, the doctors suggested that if his sweetheart married him, it might help to strengthen the wounded lad’s grip on life. The Peebles lass flew to her lad with a full bridal attire provided by Anna.

Anna was President of the Peeblesshire branches of the League of Wives and Mothers. She held this office to the end. She had, I think, more pride in this office than in most others she held. She enjoyed saying. “I am neither wife nor mother, so they made me President.” She always attended the meetings of this organisation at Peebles and Innerleithen. She spoke at every meeting, and usually voiced the thanks of the women to the speaker of the day. Anna, however, did not remain on the platform. She moved freely among all the women, some old and infirm and others young and newly married. They were drawn from all sections of the community. How these women enjoyed their brief chat with Anna, who seemed to know them all, their families and their troubles! No presentation of Anna Buchan would be complete without this picture of her moving among the women, shaking hands and smiling, and asking questions, and being utterly absorbed in the answers. This was the daughter of the Manse doing the work she first learned in her father’s Church. The sophisticated might be puzzled by this expenditure of herself, but for Anna long ago there had come a call to cheer ordinary folk, and she obeyed it to the end.

When Anna began to work on Unforgettable, Unforgotten, she had some doubts about writing it. John in his Memory Hold the Door had written an inspired book which has gone into many editions. He did not choose to write of the more personal aspects of his life. It was these aspects which mainly engaged Anna’s interest. Lady Tweedsmuir gave her much encouragement and, as Anna proceeded, her pleasure in chronicling “the fount of all her memories” increased. To Anna the friendship of Susan Tweedsmuir grew more and more precious, and the inevitable sadness of the last years was made less so by the charm and intelligence of Susan’s endearing companionship.

Anna’s health was still very good, but friends began to say that she was ageing a little. This only meant that she moved a little more slowly. She was as erect and alert as ever. Her bright eyes were as keen as ever, and her zest unimpaired. She accompanied Walter to “cures” where he sought alleviation from arthritis, but no opportunity of theatre-going was foregone by either of them. She began work on another novel with its opening chapters set in Priorsford in the early days of the war. Old friends were to appear as well as new ones, including an attractive young Canadian.

The publication of Unforgettable, Unforgotten in October, 1945, gave Anna much pleasure. The book received a warm welcome from all types of reviewers, and sales were only limited by the then prevailing restrictions on paper. An enormous number of letters poured into Bank House. It was just and appropriate that one who had given so much happiness and comfort to others should be given such warm-hearted and sincere assurances of her fine achievement. The book not only pleased her many readers anxious to read their favourite author’s own story; it helped substantially to round out the saga of the Buchan family, one of which had attained to the highest public honours and an abiding place in literature, while another suffered the bitterness of affliction; one to the briefest life of fragrant beauty; another to sacrifice in early manhood for King and Country; another to long and valued service to the community, and another with the gift to make an empire of friends through telling the story of the romance and sorrows of their lives. John had told his part of the story in his own way. Susan Tweedsmuir in John Buchan by his Wife and Friends, published in 1947, revealed what sharing in that life and joining the family meant. Anna told how the story began, and revealed the sources of the family’s strength, and the firmness of the bonds that held them together through the years unimpaired by great changes, tragedy and success.

The day after I had read the copy of Unforgettable, Unforgotten she had sent me, I said to her, “That invalid girl in the Glasgow slum was right. Your life is a fairy tale come true.”

Anna smiled. Her eyes shone. The years seemed to fall from her. I could see she was reliving some wonderful part of the fairy tale. I did not disturb her reverie which she broke with a sigh. “Yes,” she said simply, “I have so much to be thankful for.” I felt then that for her, though the sorrows had been severe the joys outweighed the sorrows; the darkness and the mystery had been redeemed by romance and gladness. Her thankfulness to the Creator of all things was as genuine as her frank and simple faith that the Christian verities were central to human life.

Anna Buchan was a Christian. Worship was the clue to living, so she was constant in attendance at Divine Service. On first coming to Peebles she had worshipped at the Church in Eastgate and, later, when union took place, at the Old Parish Church which nobly flanks the west end of High Street. Every Sunday morning as the bells pealed out a familiar air, Anna crossed the roadway to mount the flight of steps to the sanctuary.

All the letters welcoming the autobiography were cheerfully answered. Another happiness was the safe return of her three nephews from the war.

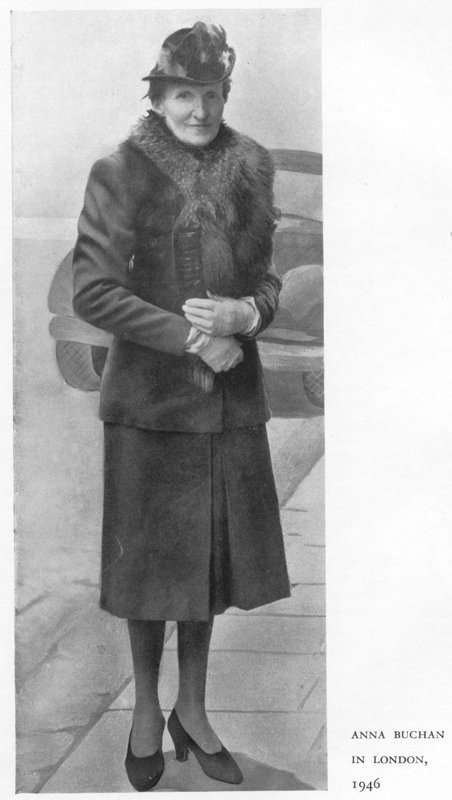

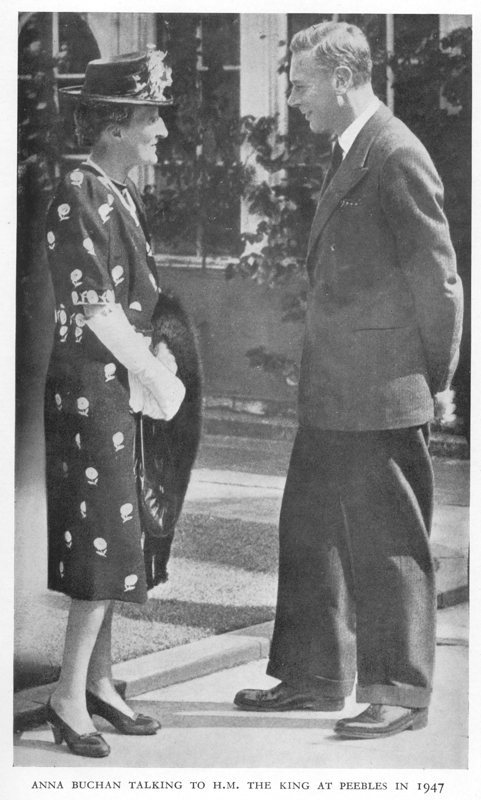

In the summer of 1947 the Borders were stirred by a visit from their Majesties, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by Princess Elizabeth, Princess Margaret and the Duke of Edinburgh, then Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten. This visit was the occasion of an impressive demonstration of Border loyalty to the throne. Peebles, no less than the other Border towns and villages, welcomed their Majesties with thunderous cheers. Anna and her brother had tea with the King and Queen and other members of the Royal Family. A picture taken by a press photographer of the King engaged in conversation with Anna shows her exactly as she was in her last years.

Walter’s health grew worse, and Anna’s concern for her brother naturally increased. Then at Christmas, 1947, her own health for the first time became troublesome. Indisposition continued and worsened. The following May she went to Edinburgh for an operation. Complications followed which taxed her strength. Anna faced these ordeals bravely, but when weakness continued, she wanted to return home. Instinctively, she wished to end her course beside the river she and her people had loved so much for so long.

Walter decided to retire from his public positions in the town and county. Public recognition was made of the services he had given, for forty-two years to the community. Peebles knew it had been fortunate in retaining all these years the devoted service of such a brilliant man. Anna was unable to accompany him to the dinner given to him by the Town Council. So Walter went alone. He only of the Buchans survived to voice a public farewell. He referred with justifiable pride to the fact that his forty-two years completed over a century of service by his family to the town.

Through the summer into the autumn, when Anna’s town is perhaps at its best, she grew weaker. But she was still a bright and cheerful spirit; and she still wrote letters. These wonderful last notes of encouragement and help said little about herself, and those who received them will cherish them. Only the last weakness could keep Anna from writing.

The inevitable hour approached. The door was closed against the world. Only Walter and Susan shared the closing chapters.

November was a month in which Anna rejoiced to pile the logs on the fire and draw the curtains. On the forenoon of the 24th November, 1948, her heart fluttered and failed, and the final curtain was drawn.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

A vast crowd filled the Old Parish Church for the Memorial Service. All the people of Peebles lamented Anna Buchan’s passing and found it difficult to believe that they would never again see her walk their bright High Street and return her greeting. They had the feeling that, though Anna had lived a long life, her death seemed premature, because they had always known her to be so gay of heart, and so in love with living.

“Is life a boon?

If so, it must befal

That Death, whene’er he call,

Must call too soon.”

Anna shared that sentiment, but through a persistent devotion, through her happy books and her ministry of comfort, she had nurtured for herself and many others the Blessed Hope that from the dust of this earthly existence there blossomed a richer, fairer Life.

Susan Tweedsmuir

It is very hard to write about someone you have dearly loved and whose death has left you with an infinite sense of loss and desolation.

Many of the things which Anna and I most deeply shared are too intimate to be written about, and Anna was the very soul of reticence. She would not, I know, wish that anything should be written about her which would have violated her fastidious reserve, so that my task, as I say, is not an easy one.

A great deal has been written about the love of sisters through the ages, even aunts have had pages to themselves in memoirs, but am I mistaken in thinking that the sister-in-law relationship has often been the target of scorn? And yet sisters-in-law can be very happy together, and Anna and I were very happy always in each other’s company. Our relationship had the warmth of sisterhood with the sparkle and fun and difference of outlook which sprang from our diverse upbringings.

I had been engaged for a short time to John when I first met Anna. He had brought his mother and her to London and installed them at Brown’s Hotel. Anna was very charming to look at with her bright hair and blue eyes and her pretty soft colouring. When we first met it was surprising that we understood each other at all; we literally spoke different languages. I had spent a good deal of time abroad, having been two winters in Egypt with an uncle and aunt, and I had also lived for months both in Germany and Italy. Anna had been abroad with John on mountaineering expeditions and had proved herself a bold and reliable climber, and once for a short trip to the Loire, but otherwise she had never left her native shores, so that any sophisticated remarks I made went completely wide. (This was soon partly evened out by Anna going to India to stay with her brother Willie, from which expedition she returned with her always receptive mind broadened and fertilised.)

I knew little or nothing of Scotland. True I had had a glimpse of that country by staying in several large country houses, amongst parties of people assembled for shooting and fishing, but I was completely ignorant of rural Scotland, industrial Scotland, and the life of a town like Peebles and Kirkcaldy.

My mode of life was completely foreign to Anna. I lived with my mother and sister in a big house in Upper Grosvenor Street. My mother was the centre of a complicated group of relations who were mainly landowners in a large or small way who moved to and from the country. Anna was not much interested in my life, and I felt that it was up to me to understand hers. Where we both showed wisdom was in concentrating on our likenesses rather than our unlikenesses. We both loved books and the theatre and we both laughed at the same jokes, and we left it at that.

I was soon fascinated by some aspects of my new family. They possessed the power of telling stories in a remarkable degree, and had what amounted to genius in recounting any incident old and new. It was always such fun to go for a drive with Anna and her mother. My mother-in-law could tell us something about the inhabitants of each little Peeblesshire farm. She excelled in terse comments, and I remember her saying once of a woman on a farm “she was the kind that would let a fire go out when she was sitting in the room all the time.”