The Rise and Fulfilment of British Rule in India

Edward Thompson & G. T. Garratt

‘Indian history has never been made interesting to English readers, except by rhetoric.’

— The Times, February 25, 1892‘The real truth is that the public mind cannot be brought to attend to an Indian subject.’

— The Duke of Wellington, December 21, 1805

Preface

A history of modern India presents in the writing certain technical difficulties, which are mentioned, not to excuse the shortcomings of this work, but to suggest deficiencies which the reader must supply by further study and examination.

-

Without making the book a mere ‘charnel-house of facts’, it would be impossible to describe the internal history of the many semi-autonomous States, and of the Provinces, which have also developed their own characteristics. Burma, in particular, requires separate treatment. In this history the States and Provinces can only be considered in relation to the Central Government, or to India’s life as a whole. Exigencies of space, as well as a desire for unity, have enforced this limitation. Similarly, though we have tried to remind the reader continually that in British India there was an increasingly vigorous intellectual and religious life, influenced profoundly by English administration and literature, yet it was impossible to treat this with adequacy in a book whose range continually tended to make it too bulky for any but a specialist public.

-

The available sources for the period under consideration are predominantly British. Many important official documents and some recent histories were written, consciously or unconsciously, with an eye to certain criticisms which have been made in India and abroad. The growth of Indian nationalism has accentuated a bias which is often unfavourable to Indians, individually and collectively. The point is illustrated in the Bibliographical Note. It has been taken by the authors to justify a much greater use of contemporary quotation in the earlier part of this work.

-

The historian’s task has been made more difficult by the animosities which have distracted the world during the last twenty years, and by their repercussions, official and unofficial. The mischievous tendency to make historical truth subservient to administrative expediency has been increased by changes in legal practice and procedure, which operate as an effective censorship. An author may be asked to substantiate statements of fact by direct evidence, which would frequently entail collecting Indian witnesses, often illiterate, bringing them to England, and producing them before a court in which their testimony would be discounted. The freedom with which the Mutiny was discussed during the subsequent two decades would have led, under present conditions, to innumerable causes célèbres involving the financial ruin of many concerned. The authors believe that it is as necessary and no more difficult to write objectively about recent events than about those of the last century. But official secretiveness, of which there was little before the Mutiny, combined with this informal censorship, makes it almost impossible to supply the ‘penetration, accuracy, and colouring’ which Dr. Johnson demanded of the historian.

-

In the spelling of Indian proper names and names of places, and in the anglicizing of Indian words, the system in general use among scholars of all countries has been adopted. We have, however, left certain names and words in the forms familiar to those who have lived in India, and used them constantly. Thus Cawnpore is used instead of Khanpur, ryot instead of raiyat, Punjab instead of Panjab. We have eschewed marks of quantity, as we have written not for Sanscritists and Arabists but for the student of history. An arbitrary line has to be taken between consistency and pedantry.

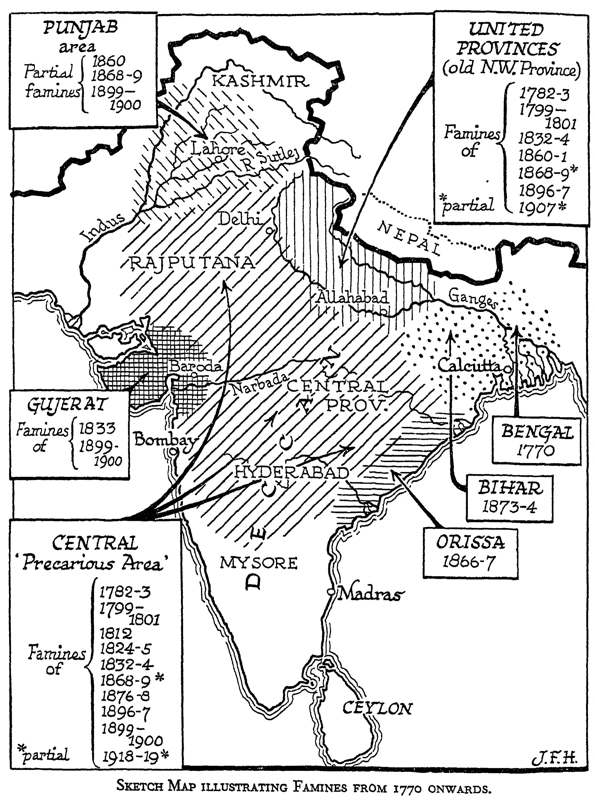

We should like to thank Mr. J. F. Horrabin for his valuable sketch map illustrating the famines.

Note to Second Edition

This book received a generous welcome, and brought many private communications and suggestions, both from India and England. Sir William Foster, C.I.E., Sir Algernon Law, K.C.M.G., C.B., Sir Verney Lovett, K.C.S.I., Mr. S. K. Ratcliffe, Mr. K. M. Panikkar, Mr. P. C. Lyon, C.S.I. Mr. Philip Morrell, Mr. G. E. Harvey, I.C.S., Mr. H. G. Rawlinson, C.I.E., Mr. E. F. Oaten, Sir T. S. Macpherson, C.I.E., Rao Saheb Sardesai, Mr. G. C. Dutt, and Sir Richard Burn, C.S.I. are among those who provided definite criticism of fact or opinion.

Special apologies are due to Mr. B. C. Allen, C.S.I. who in 1907 was shot in the back, when District Magistrate at Dacca, an attack we called fatal. We are delighted that Mr. Allen was himself able to point out our error.

Book I

The Time of Trading. 1599-1740

‘The life of man is so precious, that it ought not lightly to be exposed to dangers. And yet we know, that the whole course of our life is nothing but a passage unto Death; wherein one can neither stay nor slack his pace, but all men run in one manner, and in one celerity. The shorter liver runs his course no faster than the long, both have a like passage of time; howbeit, the first not so far to run as the later.’

— A Discourse of Trade from England unto the East Indies; answering to diverse Objections which are usually made against the same. By ‘T. M.’; 1621.

Chronological Table

1571. Battle of Lepanto.

1579. Drake’s Circumnavigation of the Globe (1577-80). Foundation of the English Turkey Company.

1580. Portugal becomes a Spanish dependency.

1583. Sailing of the Tyger.

1588. Defeat of the Armada.

1599. Foundation of the East India Company.

1603. Death of Elizabeth.

1612. Captain Best defeats the Portuguese off Swally, Western India. East India Company’s first factory established at Surat.

1615. Sir Thomas Roe sent as ambassador to the Mogul Court.

1620. Defeat of the Portuguese by Persia and the East India Company. Capture of Ormuz.

1623. Massacre of Amboyna.

1627. Shah Jahan becomes Emperor.

1630. Indian Great Famine. Further defeats of Portuguese off Swally.

1633. William Methwold President at Surat.

1635. East India Company and Portuguese establish a truce. Charles I gives charter to Courteen’s Company.

1640. Portugal recovers independence of Spain.

1641. Foundation of Fort St. George (Madras).

1642. Permanent peace between East India Company and Portuguese. Civil War breaks out in England.

1649. Execution of Charles I.

1652-54. First Dutch War.

1657. Amalgamation of East India Company and Courteen’s Company. A new Charter granted.

1662. Sir George Oxinden President at Surat. Bombay ceded to Charles II.

1665. Bombay handed over to British.

1665-67. Second Dutch War.

1668. Bombay handed over to East India Company. Foundation of French East India Company.

1669. Gerald Aungier President at Surat.

1674. Sivaji the Maratha proclaims himself an independent king.

1680. Death of Sivaji.

1683. Keigwin’s rebellion, Bombay.

1686. War between East India Company and Mogul Empire. Temporary ruin of English factories in Bengal.

1687. Madras made a municipality under a mayor. Bombay supersedes Surat as chief Company trading station in Western India.

1690. Foundation of Calcutta. Foundation of Fort St. David (Cuddalore).

1698. Rival Company established in England.

1702. Accommodation come to between two rival Companies.

1707. Death of Aurangzeb. The Calcutta settlement is made independent of Madras.

1714. Surman’s embassy to the Mogul Court.

1726. Mayor’s courts established in all three Presidencies.

1727. Establishment of Peshwa’s power. Rise of Maratha chieftains.

1739. Maratha conquest of Malwa. Nadir Shah of Persia invades India and sacks Delhi.

Chapter I

Foundation of the East India Company

Early trade of East and West: first English attempts to gain share of Eastern trade: Thomas Stevens: sailing of the ‘Tyger’: Ralph Fitch: foundation of East India Company and Captain Lancaster’s first voyage: Edward Monox, William Adams, Richard Cocks: Captain Henry Middleton: Best defeats Portuguese off Swally: pirates: Sir Thomas Roe’s embassy: Roe on the Dutch and their policy: Roe’s overtures to the Portuguese Viceroy at Goa: Captain Shilling’s victories and death: capture of Ormuz: Dutch insolence and hostility: Massacre of Amboyna.

The commerce of East and West for millenniums moved by the Persian Gulf, across Syria, or up the Red Sea, through Egypt; in the Middle Ages Venice controlled its Western outgoings until the Turks overspread the Levant and taxed and pillaged much of the traffic out of existence. Spain at Lepanto (1571) mastered the Turkish fleet. But as the sixteenth century drew to its close, events continued to push the Eastern trade away from its immemorial routes, and increasingly into one main channel, the perilous but possible sea-way which Vasco da Gama had opened up, rounding the Cape to India (1499). Portugal had succeeded to the primacy of Venice in navigation; and when Spain annexed Portugal (1580), the Dutch, who were in rebellion against Philip II, could no longer buy through Lisbon the spices and the rich stuffs their painters have made so familiar to posterity, and the ancient if loose alliance of England and Portugal finished. Spain considered it her business to be the hammer of all heretics, an ambition which brought her to grief when Holland managed to turn ‘her despairing land-revolt into a triumphant oceanic war’.*

Between Elizabeth’s accession (1558) and Cromwell’s death (1658) a fiercely mercantile England hunted for markets, when necessary fighting for them. In 1579, Drake, circumnavigating the globe, reached the veritable Spice Islands, and set up rights of prior discovery which the East India Company, a generation later, were to try vainly to uphold against the monopolising Dutch. He was believed to have entered into treaty engagements with the King of Ternate; and his voyage was the most conspicuous of many exploits that shook his countrymen free of insularity. When he captured the San Filippe (1587), he secured papers which fired imagination with their witness to the wealth that lay in commerce with the Indies.

The year of Drake’s reaching Ternate was also the year when the first Englishman set foot in India proper. This was Thomas Stevens, the Jesuit missionary, whose letters from Goa to his father are supposed to have done much to arouse English eagerness for the eastward attempt. Stevens relates the gravity and pomp with which the fleets of Portugal went out:

‘The setting forth from the port, I need not tell how solemn it is, with trumpets and shooting of ordnance. You may easily imagine it, considering that they go in the manner of war.’

His own voyage in one of these ships of Lisbon he thought a good one, since out of a hundred and fifty sick only twenty-seven died.

But the English were to encounter even greater odds, held trespassers by Spain and Portugal, who claimed to hold the East in fee from the Pope, and in the Spice Islands persecuted to death by the Dutch, their nominal allies. Their ships were of slighter tonnage, in smaller groups; they were learners and alone, where their predecessors had stations and helpers along the route and an accumulation of knowledge:

‘The English ships, though Weatherly and heavily gunned, were small; if food and water failed, as they often did when they kept the sea for any length of time, it was chance work replenishing them; every port was armed and hostile; every ship they met was an enemy and had to be fought or run from (but the English seldom ran); to reach India was to sail into a nest of wasps; they sailed as poachers and pirates and so were without the Law, and the navigation was all sheer guess-work.’*

The right of trade with the Levant had been obtained from Sultan Amurath (Murad) II, in 1579, and a Turkey Company had been formed in England. In 1583 a ship called the Tyger was sent to endeavour to open up commerce further east still, with India. How keenly men’s eyes were straining abroad we can see from Shakespeare’s reference, twenty years later (one which his audience, aware of that sailing’s significance, took as easily as we should take an allusion to any contemporary long-distance flight or an Everest expedition to-day):

‘“Aroint thee, witch!” the rump-fed ronyon cries.

Her husband’s to Aleppo gone, master of the Tyger.’*

The Tyger took her merchants as near Aleppo as the sea permitted. Then five of them—John Eldred, John Newbery, Ralph Fitch, William Leeds and James Story—entered on the overland route to India, which was beset with ‘defrauding Turks, blackmailing Arabs or stealthily obstructing Venetians’. Eldred,

‘halted between Basra and Baghdad, was to be, as it were, the shaft of the spear, the other four its head thrusting forward into India. Though shaft and head came apart the thrust did in fact go home’.*

Portugal had locks at Basra and the Gulf’s entry; at Ormuz, Newbery, Fitch, Leeds and Story were arrested, and reached India as prisoners. Here their countryman Stevens befriended them—a generous deed, seeing that he himself, if in England, would have been liable to a traitor’s death. Leeds, whose craft of jeweller made him useful to decorate the numerous churches that Portuguese missionaries were building, became a monk. The other three, with a Dutch merchant’s assistance, escaped: the painter Story entered Mogul service; Newbery got to Lahore and with ‘sheer insolent courage’ set off home across Persia, and we do not know what became of him; Fitch wandered over North India and Burma, and to Ceylon, ‘walking serenely into traps and out again’,* reappearing in London in 1591. He and Eldred were present when eighty City merchants met in Founders’ Hall, September 24, 1599, to establish the East India Company; the Company’s Court Minutes contain the note (December 31, 1606):

‘Letters to be obtained from King James to the King of Cambaya, governors of Aden, etc. . . . their titles to be enquired of Ralph Fitch.’

In shadow of the imposing fabric of the British Raj these foundations appear sordid. We went honourably, thinking it no shame to be merchants. But we are attacked as a folk who came as suppliants seeking leave to trade, and by devious ways of treachery became rulers of a distracted, peace-loving, helpless land. Yet the miracle is not that commerce ultimately expanded into empire, but that for such a vast of time we were traders and nothing else. Of all the European interloping nations we were the last and most reluctant to draw the sword, even in defence. Nor was the name of merchant synonymous, as seems to be suggested, with huckster. Our merchants walked and sailed through deaths Ulysses never knew, and did it with cool good-humour.

The Tyger bore Elizabeth’s letter “To the most invincible and most mighty Prince, Lord Zelabdim Echebar, King of Cambaia’, stating frankly that trade was the aim. But no Company was formed until in 1599 the Dutch put up the price of pepper from three to six and eight shillings a pound. Even more than for gold, men were ready to risk their lives for spices:

‘The Elizabethans lived on salt meat from autumn to spring; their fresh meat was of poor quality in general; for the good of the fishermen the Law compelled them to eat fish more often than they cared about, and with all this insipid food their craving for pungent flavourings was probably and naturally much stronger than ours. They liked heavily spiced drinks, moreover, for they had no tea.’*

The East India Company was formed to traffic in the luxuries of the rich, in spices, silks, gems, bezoar stones, camphor, indigo, sulphur. Two centuries later, its wealth came through the amenities of the middle classes; tea had supplanted pepper, cookery books now contained recipes for rice. A resolution was passed ‘not to employ any gentleman in any place of charge’; and the Company requested to be

‘allowed to sort their business with men of their own quality, lest the suspicion of the employment of gentlemen being taken hold upon by the generality, do drive a great number of the adventurers to withdraw their contributions’.

There was suspicion of aristocratic disinterestedness and ability alike; and, although members of the nobility adventured capital in the Company, the influx from what used to be considered the higher classes did not become considerable until Wellesley’s time.

The first voyages were hardly towards ‘India’ at all (as we understand the term), but further eastward. A commission was granted to Captain Lancaster, January 24, 1601, to voyage for the Company ‘at their own adventures Costs and chardges as well as for the honour of this Our Realme of Englande’. The Realm’s honour was to prove a long- continuing hindrance. In accordance with the doctrine that to export specie impoverished a country, Elizabeth gave leave to take only £30,000, of which £6,000 must carry her arms and effigy,* tokens so valueless that the Company petitioned her successor James for permission to take only £20,000, with no ‘English’ coins at all. Protests to Elizabeth that her name was unknown in the Orient had been opposed with the very proper reply that for this very reason these coins must be used, to the end that her greatness might be blazed abroad.

Captain Lancaster sailed to Achin, in Sumatra, and returned, November 5, 1603, with cloves, cinnamon, lac; and 1,030,000 lbs. of pepper, whose sale was forbidden until King James’s own large private stocks* were disposed of. Alarmed and exasperated, the Company pointed out that they could not pay their mariners or risk a second voyage; and if they did not send another expedition, their factors* left with Eastern princes as hostages might be put to death. With their pepper unsold, they could not even discharge their customs dues to His Majesty. A compromise was arranged, by payment to influential persons. Captain Lancaster was knighted, and a second expedition set out under Henry Middleton, March 3, 1604. Between 1601 and 1618 nine voyages were made, mainly (at first exclusively) to the East Indies, not to India.

The exigencies of a commercial organisation working within a wide range of hazard required frankness of both employer and employed. The Company’s correspondence is of unsurpassable interest and individuality. The irascibility of the Directors’ sharp comments to their Bantam factors (March 11, 1607)—‘at which ignorance of you, to buy such spices, we conceive the Indians do rejoice’—can be matched by the criticism of their agent at Jask (Persian Gulf), in December 1617:

‘Touching the pieces and petronels you sent, you were much abused in them, for they were nothing near worth the money you paid for them per invoice. It seems also they took wet in bringing aboard, for many of them were so rusty that we were forced to work off all the damasking to make them clean.’*

After Japan was added to the Company’s far-flung bazaar (in response to a letter* from that remarkable man William Adams, sent October 23, 1611, to ‘his unknown friends and countrymen’ and to ‘the Worshipful Company’ in particular), Richard Cocks wrote from that land (1617) that he was amid a people unable to appreciate good things:

‘They esteem a painted sheet of paper with a horse, ship or a bird more than they do such a rich picture. Neither will anyone give sixpence for that fair picture of the Conversion of St. Paul.’*

The heathen’s natural recalcitrance was perhaps heightened by the fact that Japan was passing through a great artistic period.

The Company started with separate voyages, changed to a modified joint stock (three voyages being covered by one subscription, in place of new subscriptions for every voyage) in 1614, and a permanent one, 1657. In 1609 their charter was renewed and the monopoly of Eastern trade made theirs in perpetuity. More of the nobility risked capital. Profits, ‘though irregular, had been large’.* The Company on the whole were ‘gentle masters’, and their servants in return were zealous and honest in collecting and collating information. Strict cleanliness on shipboard, in which the Dutch were held up as far superior, was enjoined repeatedly, and all were warned to be watchful: ‘still expecting and fearing evil, though there be no cause’; ‘suspect all, how friendly soever they seem’.

Captain Lancaster had sold iron, tin, lead, and exchanged specie for spices; the woollen goods for which England was so anxious to find a vent, now and later, proved almost unsaleable in a tropical climate, and wasted away in godowns. In 1608 the Company’s factors in Bantam and the Moluccas wrote pointing out that the people there were big purchasers of Indian calicoes. To obtain these, to exchange for specie, a trading post in India was essential. Permission was obtained from the Emperor Jahangir, 1608, to settle at Surat, the chief port of Western India; the Portuguese, however, were still too powerful for the leave to become effectual until 1612. Sir Henry Middleton attempted to open up a Red Sea trade; was received with apparent friendliness, but enticed ashore, where his company were taken prisoners (after several had been killed). He himself and a few others presently escaped to their ships, and blockaded Mocha, whose governor received such missives as this (May 18, 1611), in reply to his efforts to placate Middleton and persuade him to sail away without recovering the rest of his men:

‘. . . If you advise the Basha, as you say you will, what is that to me? I am no subject of the Basha’s but a servant to the King of England, besides whom I will not be commanded by any king under heaven. And for the referring of matters to the hearing of our betters, as you say, at Constantinople, I know my cause so good that I hope to have remedy against you, but you dare never show your face there. You sent me by the bearer, Nahuda Mahomet, a foolish paper, what it is I know not, nor care not. In God is my trust, and therefore respect not what the devil or you can do with your charms.

At present I cease and rest

As you shall deserve

Henry Middleton.‘This is all interpreted to the bearer right as it is written.’*

England does not yet know the quality of the seamen who in the discouraging days of James carried on the Elizabethan tradition. The Company was superbly served. Middleton revenged both his own Arabian imprisonment and the unwillingness of the Surat authorities to allow the factory for which Jahangir had given consent, by holding up traffic between Gujarat and the Red Sea in 1611. Next year Captain Best gave the Portuguese the first of several sound drubbings off Swally, close to Surat. The Mogul Empire, helpless at sea, took note of the new naval power hopefully, willing to think it a match for the Portuguese, against whom it had many grievances. The factory was established that year. In 1614 and 1615, Nicholas Downton* won yet greater victories off Swally, announcing his success in a despatch as honourable to its writer as its news:

‘The Guzerats ready to embrace a peace upon a parley with the Portugals, doubting of our success; for the force of the Portugals was great, insomuch that it would not have gone well with us if God had favoured their cause. I never see men fight with greater resolution than the Portugals; therefore not to be taxed with cowardice as some have done. . . . If the Portugals had not fallen into an error at the first they might have destroyed the Hope, and by likelihood the rest hastening so to her aid. They renew their strength again within ten days; we feared new dangers and prepared accordingly. They set upon us by fireworks. The Portugals with all their power departed from us and went before the bar of Surat. We were afraid they would set up their rest against the town; but they were wiser. Much quicksilver lost for want of good packing. The ships’ muskets break like glass; the cocks and hammers of snaphances evilly made. The false making of sold pieces hath disgraced them. The axletrees of your great ordnance made of brittle wood. The tracks must be turned when the timber is seasoned. Match too scanty. Want of iron chains to lay upon our cables to keep them from cutting. Defect in our flesh; our oil most part run out; our meal also spoiled by green casks; so of our pease and oatmeal. No scales nor weights. Much of our beer cast overboard, being put into bad casks.’*

The wrath against ‘interlopers’*—which persisted long after the Company’s solely trading days—was justified in the seventeenth century. Efforts in isolation would have been doomed, in seas swarming with enemies. Moreover, the Company were naturally held responsible for the acts of all Englishmen,* in a period when piracy was the crime commonest in these distant waters. England abounded in skilful seamen, trained in the prolonged wars with Spain and now “out of a job’, thanks to the peace King James was resolute to keep. Sir Thomas Roe, the Company’s first ambassador at the Mogul Court, warns his employers (February 14, 1618):*

‘That these seas begin to be full of rovers, for whose faults we may be engaged. Sir Robert Rich and one Philip Barnardoe set out two ships to take pirates, which is grown a common pretence of being pirates. They missed their entrance into the Red Sea (which was their design) and came for India, gave chase to the Queen Mother’s junk, and, but that God sent in our fleet, had taken and rifled her. If they had prospered in their ends, either at Mocha or here, your goods and our persons had answered it. I ordered the seizure of the ships, prizes and goods, and converted them to your use; and must now tell you, if you be not round in some course with these men, you will have the seas full and your trade in India is utterly lost and our lives exposed to pledge in the hands of Moors. I am loath to lie in irons for any man’s fault but mine own. I love Sir Robert Rich well, and you may be pleased to do him any courtesy in restitution, because he was abused; but I must say, if you give way, you give encouragement. I had rather make him any present in love than restore anything in right.’

Rich (afterwards Earl of Warwick) was too powerful an offender to be easily penalised. The seizure of his ships led to prolonged dispute; his claim to £20,000 compensation was finally referred to arbitration.

But the Company, though looking austerely on piracy they had not authorised, themselves picked up quick profits by ‘rummaging’ ships to which their Portuguese rivals had given passes; and we have seen that in their difference with the Governor of Mocha they held up ships from India.

The disadvantages of being represented solely by merchants (a profession which the Mogul Court despised) grew grievous. The Company’s first envoys to the Central Government at Agra were unable to stand against the constant objection of the Portuguese that they and their employers were men of lowly rank. The prejudice against gentlemen was reconsidered; in 1615 Sir Thomas Roe, courtier, sent as the Company’s and King James’s ambassador, entered on four years’ magnificent service at the capital of a monarch casual and drunken and on occasion indescribably cruel, who had one question only, what presents he brought or could procure in the future. Roe’s solemn, stiff demeanour invited impish treatment, such as the Empress’s prank when she sent to his bed at midnight a female slave who had offended, ‘a grave woeman of 40 years’. Jahangir when liberally inclined would send a male malefactor or a wild boar (tusks to be returned); in June 1616, Roe (whom his employers expected to be liberally rewarded by imperial munificence) noted that his accessions from this source had been ‘hoggs flesh, deare, a theefe, and a whore’.* But the Court learnt that ‘the English were not all obsequious merchants or rough sailors’. He failed to obtain the explicit contracts he worked for, a treaty on Western lines being ‘an idea utterly alien to the political system of the Moguls’;* but his chaplain, Edward Terry, claimed not unfairly, that he was ‘a Joseph in the court of Pharaoh, for whose sake all his nation seemed to fare the better’, despite the Company’s meanness:

‘frugality prescribed his allowances, his retinue, and even the present to the Mogul, with little conformity to the sumptuous prejudices of the most magnificent court in the universe’.*

He was heedless of safety, comfort or esteem, of spirit nobly disdainful as Doughty’s when he wandered poor and unfriended among Bedouins.

Roe’s Journal and correspondence show up not only his integrity but his far-sightedness. The Company were extraordinarily lucky in such a representative. He could write with high controlled indignation to the Emperor himself or his favourite son (afterwards Shah Jahan). His letter of October 19, 1615, to the Governor of Surat, is eloquent of his cruel perplexities and his character and courage:

‘The injuries you have offered me, contrary to the faith given by your King, to all civility and law of nations, being a free Ambassador, and contrary to your own honour and promise, forceth me to send you word I am resolved not to endure it. I come hither not to beg, nor do nor suffer injury. I serve a King that is able to revenge whatsoever is dared to be done against his subjects. . . . I am sorry for nothing but that ever I vouchsafed to send you any remembrance of me, of whom in love you might have received anything, but by this course, of me, nor my nation, I am resolved you shall never get one pice; assuring you I am better resolved to die upon an enemy than to flatter him, and for such I give you notice to take me until your master hath done me justice.’

He saw through the imposing facade of Mogul pomp, saying of Jahangir, in often-quoted words:

‘His greatness substantially is not in itself, but in the weakness of his neighbours, whom like an overgrown pike he feeds on as fry. Pride, pleasure, and riches are their best description. Honesty and truth, discipline, civility, they have none, or very little.’

Not least of Roe’s perplexities was his knowledge that all his proud carriage was bluff. Behind the English Company was only the cowardly foreign policy of James I.

Every year it became clearer that the Company’s destiny was restriction eastward and expansion westward. The trade with Japan amounted to very little; soon that country relapsed into savage xenophobia. The English were to be driven bloodily and ignominiously from the Spice Islands by the Dutch, whose whole Republic

‘was virtually an association for the purposes of navigation and trade; the Dutch companies were connected organically with the constitution of the States General. And since in Holland the people at large were merchants and mariners, their commercial policy was stronger, more stiffly resolute, and better supported than that of States ruled by a Court and a landed aristocracy whose aims and interests were diverse and conflicting.’*

Roe noted their errors, as viewed from his own employers’ rigid standpoint of merchants:

‘A war and traffic are incompatible. By my consent, you shall no way engage yourselves but at sea, where you are like to gain as often as to lose. It is the beggaring of the Portugal, notwithstanding his many rich residences and territories, that he keeps soldiers that spends it; yet his garrisons are mean. He never profited by the Indies, since he defended them. Observe this well. It hath been also the error of the Dutch, who seek plantation here by the sword. They turn a wonderful stock, they prowl in all places, they possess some of the best; yet their dead pays consume all the gain. Let this be received as a rule that, if you will profit, seek it at sea, and in quiet trade; for without controversy it is an error to affect garrisons and land wars in India.’

The Dutch were too strong for their nominal allies, whom they pressed steadily and ruthlessly out of Far Eastern seas. The English Company had no choice but to withdraw from a struggle for which they were not yet ready. Meanwhile, it was with the Portuguese, whose waning power Roe contemptuously and accurately assessed,* that they first came to grips, both off India and in the Persian Gulf.

European nations kept no peace east of Egypt. But (especially when he began to plan a Spanish marriage for his son), King James’s policy was peace, and at any price. Roe, under instructions from him, on October 20, 1615, sent the Portuguese Viceroy at Goa a missive which he seems to have considered conciliatory. It reminded the recipient of the repeated thrashings his people had experienced in Elizabeth’s time, and warned him that worse would come if they did not eagerly promise to amend their ways now. It was signed ‘Your friend or enemy at your own choice, Tho. Roe’; and was unacknowledged and unanswered. The year following this menacing overture, Roe persuaded the Company to open up trade in the Gulf. This involved the extirpation of the Portuguese from these regions, a task begun by Captain Shilling, another of the fine seamen England had available for exploits which the historic muse scarcely noted even in their doing. He won victories off Jask, December 16 and 28, 1620, dying of his wounds, January 6, after lingering ‘very godly and patient’;

‘Here lies buried one Captain Shilling, unfortunately slain by the insulting Portugall: but that his bones want sense and expression, they would tell you the earth is not worthy his receptacle, and that the people are blockish, rude, treacherous and indomitable.’*

The Portuguese, seeking to prevent English entry of the Gulf, had begun the actual fighting. Furthermore, the Shah made an alliance with the Company against Portugal a condition of permitting trade, and demanded naval assistance in reducing Ormuz, the island which locks the Gulf. This was provided with deep misgivings. Ralegh’s execution was a recent memory to make men wish to proceed cautiously in hostility to Spain, whose Infanta was being wooed by the Prince of Wales. It is amazing that the expedition was ever undertaken; hardly less amazing that it was carried through with impunity. The Indian factors, grumbling and disgruntled men, had some reason for their complaint:

‘Indeed (to speak truth) that enterprise was not well entertained on our parts, except upon more certain grounds and better conditions to have enjoyed the command thereof, and not to dispossess Christianity (although our enemies) to place in faithless Moors, which cannot but be much displeasing to Almighty God.’

However, Ormuz was taken, mainly thanks to the Company’s naval assistance; in one of the subsidiary actions, the capture of Kishm, the Arctic explorer William Baffin was slain:

‘Master Baffin went on shore with his Geometrical Instruments, for the taking the height and distance of the Castle wall, for the better levelling of his Piece to make his shot; but as he was about the same, he received a small shot from the Castle into his belly, wherewith he gave three leaps (by report) and died immediately.’*

Persia broke her engagements, the English foolishly handing over the fort; the partial exception in a general dishonouring of engagements was the Shah’s promise of half the customs of Gombroon (Bandar Abbas), a concession more evaded than fulfilled, causing constant friction for half a century to come, and dissatisfaction after that. The Dutch, following swiftly into the place of the dispossessed Portuguese, flatly refused to pay duties bringing benefit to their English rivals. The campaign’s profits were illusory for the Company, which had acted as the Shah’s catspaw; yet Ormuz, still a glittering name when Milton wrote a generation later, had a sheen which cost it dear, for Buckingham, Lord High Admiral, and King James (‘Did I deliver you from the complaint of the Spaniard, and do you return me nothing!’) each took £10,000 as their tenth of a mythical £100,000 loot. Moreover, this defeat, with the justifiable resentment it engendered, roused the Portuguese as the Swally skirmishes had not done. De Andrade Ruy Freire, their commander taken at Ormuz, escaped in India; he was a seaman of ability, and his exploits, during ten years of peril and not infrequent defeat, were a powerful means of turning the Company’s mind towards an enduring peace.

Nevertheless, England’s long and honourable record in the Gulf, ‘the most unselfish page in history’,* had begun.

Roe took his duties seriously, as representative of a mercantile company as well as of the King. To avoid draining specie out of England, he urged the capture of the Red Sea traffic (‘you must eat the Guzerats out of that trade’); then specie could be obtained from Egyptian merchants in exchange for spices and assorted English and Indian goods. The specie would purchase calicoes in India, which sold readily in the Indies whence spices came, and were already growing popular in England. In fine, he acted much as many think modern consuls should, as trade adviser.

This led to trouble immediately. By buying up the Gujarat calicoes the Company spoiled Surat’s Red Sea traffic; by bringing in Red Sea coral, an importation forbidden to foreigners and kept as a monopoly of Indian traders, they struck it again. This whole Middle Eastern trade was the theme of exceedingly irascible passages between Roe and the Mogul authorities, spreading prejudice in the mind of the Emperor, and still more of his son who was to succeed him as Shah Jahan. It was nevertheless persisted in, being far too valuable to be dropped.

Having demonstrated their naval importance, the Company were able to sell passes, a primitive form of insurance. This system, a source of profit to Portuguese and Dutch also, led to natural irritation when Powers warring among themselves molested shipping which had been granted passes by their rivals.

While India’s western approaches were year by year being opened up to their vessels, the Company was losing ground in the Spice Islands, their original market and aim. So long as Spain remained a menace, the Dutch needed British support. But as Spain grew pitifully helpless, the Hollanders, whose mariners were skilled and brave and whose ships were in greater force than the English, chased and sank their allies whenever they could. No doubt the English have earned their reputation for ‘imperialism’; but for imperialism at its most ruthless we must go to the Indies and the Dutch record. They beat down native chiefs into granting trade monopolies, and strove to set in force a monopoly whether a grant had been made or not; and

‘by fortifying themselves in the place wherever they settle, and then standing upon their guard, put a kind of force upon the natives to sell them their commodities’.*

Friction came to war (1618-20) so open and embarrassing that both home governments had at last to take note of it. Roe warned his employers (1618) that the Dutch

‘wrong you in all parts and grow to insufferable insolencies. If we fall foul here, the common enemy will laugh and reap the fruit of our contention. There must a course be taken at home, which, by His Majesty’s displeasure signified, were not difficult, if he knew how they traduce his name and royal authority, rob in English colours to scandal his subjects, and use us worse than any brave enemy would, or any other but unthankful drunkards that we have relieved from cheese and cabbage, or rather, from a chain with bread and water. You must speedily look to this maggot; else we talk of the Portugal, but these will eat a worm in your sides’.

The scorn and detestation manifest in these words was no mere jingoism, but throughout the seventeenth century was felt fiercely by some of the noblest Englishmen. Holland was the only enemy that stirred the magnanimous spirit of Andrew Marvell to anger.

James Mill strives to set out the imaginable justification of the crowning brutality, when in 1623 ten Englishmen and nine Japanese were arrested, tortured into alleged confession of conspiracy to seize the Dutch fort of Amboyna and assassinate the Governor, and executed with insult and cruelty. The justification amounts to nothing at all; the plot was a figment of savage imbecility and cowardice:

‘there were only twenty Englishmen all told on the island, and they unarmed civilians, while of the Dutch there were from four to five hundred, and half of them soldiers in garrison, besides eight large ships in the roadstead’.*

No redress could be hoped for under the Stuarts, but wrath smouldered until Cromwell in 1654 obtained under arbitration some belated pecuniary compensation. The outrage, coming as the culmination of years of mounting treachery and enmity, made official war inevitable whenever England found less pusillanimous rulers; as surely as any single deed ever did, it precipitated the clash of nations.

This date, 1623, serves conveniently to indicate the ousting of the English from all but precarious footing in the East Indies, and the sinking of the Portuguese star. The Mogul Empire, too, was decaying and had entered on the century and a half of gradual disintegration which was ultimately to bring English, French, and Marathas face to face as contestants for India’s sovereignty. The Company, aware of defeat eastward and with victory of doubtful value won in Persia, held in India six trading stations: Agra, Ahmadabad, Burhanpur in Khandesh, Broach, Masulipatam, Surat. Though they clung still to Malaya, with a factory established at Bantam (Java), their face was now turned to India’s mainland and away from the islands. They had won a place by the tenacity and valour of their seamen and great ambassador, and had shown the individuality and open fearless dealing which have been the strength of the English in India. Ten years of eclipse were to follow, under nerveless and hesitant men; but the virtue which had gone to their establishment was sufficient to endure until in William Methwold another man arose who could conserve what remained and rebuild the impaired foundations.

Chapter II

Era of Portuguese and Dutch Rivalry

Company’s weakness and difficulties: interference with Indian Red Sea traffic: famine in India: further victories at Swally: Dutch pressure on Portuguese: William Methwold: negotiations with Viceroy at Goa: deterioration of internal polity of Mogul Empire: civil war in England: pirates in Eastern waters: Methwold’s courage: Courteen’s Association: ‘Golden Farman’ from King of Golconda: changes in character of trade: Malabar pirates: attempts to get footing in Bengal: coffee and tea: opening up of China trade: internal discipline of Company settlements: Company begins to fortify, at Masulipatam amd Madras: foundation of Fort St, George: miseries due to English civil war: execution of Charles I and resulting embarrassments: war with Dutch: quarrels with Mir Jumla.

The factors, who had never relished either Roe’s social superiority or his stiff self-esteem, crabbed his achievement. But his insistence that to seek territory or fortify was to imitate the uneconomic methods of Portuguese and Dutch was remembered; the Company remained for over a century essentially a trading concern. Yet the seeds of inconsistency lay dormant in his other advice, that even merchants could not succeed unless respected because they could enforce respect. ‘Assure you’, he told his employers, ‘I know these people are best treated with the sword in one hand and caducean in the other’. Exercised in the naval hand, the sword entailed the minimum of expense and entanglement. He wrote (same date: February 14, 1618) to Captain Pring: ‘Until we show ourselves a little rough and busy, they will not be sensible’.

It may seem incredible that after Amboyna the English Company should have continued in ‘alliance’ with the Dutch, their executioners. Yet they did. They were so inferior that the alliance was ludicrously unequal. The factors, petty bickering men, merely grumbled; and sought to hide their loss of prestige in such consolation as the report that the Tanjore Raja

‘having heard the English to be a peaceable nation that seek not to incroach on other men’s territories, was earnest with him’—one Johnson—‘to move into us the favourable opinion he had of our nation and great desire that we should trade in his dominions. . . . The Dutch have been earnest suitors to the Naik to fortify in his country, and begun a fort at Tinegapatam; but the Naik refuseth to have them live in his country, and hath demolished what they had begun, saying he hath heard how they incroached upon other princes’ dominions and countries, and therefore should not live in his’.

So wrote President and Council from Batavia, where they had to abide under the black shadow of Dutch vigour and insolency.

It was true; the Dutch were fortifying—they were exercising all the prerogatives of sovereign power. In their Coromandel station at Masulipatam they even enforced Christian morality, beheading both parties to any irregular union of European and native. The English Company remained sojourners seeking trade alone; they frowned on factors who sought to imitate Dutch pomp and official extravagance; not until 1618 would they extend to even their representative at Surat the Dutch title of ‘President’.

The decade following Ormuz and Amboyna was one of poverty and waxing difficulty. Local governors grew more rapacious and faithless, and weaker as protectors. In 1630 came almost unprecedented famine, which did not materially lighten for nearly two years. Both from Indian and European sources comes abundant evidence of its severity:

‘an universal dearth over all this continent, of whose like in these parts no former age hath record; the country being wholly dismantled by drought, and to those that were not formerly provided no grain for either man or beast to be purchased for money, though at sevenfold the price of former times accustomed; the poor mechaniques, weavers, washers, dyers, etc., abandoning their habitacions in multitudes, and instead of relief elsewhere have perished in the fields for want of food to sustain them. . . . This direful time of dearth and the King’s continued wars with the Deccans disjointed all trade out of frame; the former calamity having filled the ways with desperate multitudes, who, setting their lives at nought, care not what they enterprise so they may but purchase means for feeding, and will not dispense with the nakedest passenger, not so much as our poor pattamars with letters, who, if not murthered on the way, do seldom escape unrifled, and thereby our advices often miscarried on the other side’.*

‘In these parts there may not be any trade expected this three years. No man can go in the streets but must resolve to give great alms or be in danger of being murdered, for the poor people cry with a loud voice: “Give us sustenance or kill us”.’*

Dutch and Portuguese were at war; but not English and Portuguese, except in the irregular fashion of the Indies. This fashion, in October 1630, resulted in a completion of the sea-victories by a land triumph behind Swally. The English pretended to disperse, ‘and marcht about the sandhills’; suddenly uniting, they attacked the Portuguese in imagined safety with their ships close inshore:

‘But ours very providently perceiving that but three of their prows could offend them, and these also so ill plied as, for fear of their own, they could not well damnify our people, they fiercely entered amongst them and in the very face of their vessels pursued them into the water chin deep; where with admirable resolution they so prosecuted their fury that even to the frigates’ sides they continued the slaughter; and having massacred the greater part, whereof many by small shot and others at handy blows with their swords and musket stocks, returned with a glorious victory and 27 Portingals brought off alive their prisoners.’

English naval prowess was known already; but this was a notable military conquest, achieved with the loss of one very fat man who died of his exertions and of some wounded who recovered—achieved, moreover,

‘in the sight of divers Moguls and other these country people, who, in admiration of so strange a manner of fight, have dispersed their letters both to the court and several parts of this kingdom, and were pleased to aver the like battle to have never been seen, heard of, or ever read of in stories’.*

These were unhappy times for the Portuguese. The Dutch were ejecting them from the East Indies, Malacca, Ceylon. Shah Jahan, the first Emperor rootedly unfriendly to aliens, succeeded Jahangir.* He began hostilities, 1631; and after three months’ siege captured their settlement at Hugli, Bengal. More than 4000 prisoners were put to death (refusing the alternative of changing their faith) with Mogul barbarity. Distracted and terrified, Portugal looked about to effect some diminution in the number of her assailants; and remembered her ancient alliance with England, from which she had been warped by annexation to Spain.

In November 1633, after years of fumbling and nerveless administration, the East India Company’s affairs again passed under a man of genuine greatness of mind and spirit, William Methwold, the greatest Englishman in India before Clive. He sounded the Jesuits, who had frequent occasion to pass through the English settlement, and they acted as intermediaries. In March, 1634, the Portuguese Viceroy at Goa replied frankly that the recently concluded Treaty of Madrid did not (he thought) apply to the Indies, but suggested an armistice pending word from Europe; should that prove unfavourable, there might be a longish interval before hostilities were resumed. Methwold then led an embassy, which was received at New Goa with gratifying courtesy, and at Goa by the Viceroy himself. Common dislike and dread of the Netherlanders had wrought to bring the belligerents together.

The truce thus made (1635), after Portugal regained her independance (1640), passed into official peace secured by treaty (1642). The new Viceroy who came in 1635 did not love the English, but explained to his master King Philip that one enemy was preferable to two. Neither truce nor peace was ever really broken; despite rubs and grievances good relations were set up. The English obtained the use of Portuguese roadsteads; the Portuguese could now transport wares not infrequently to Macao and Malacca in English ships, which were normally less liable to stoppage and search by the Dutch.

Though the Portuguese wars were over, other shadows were falling across the Company’s course. Shah Jahan, fiercely hostile to the Portuguese, was displeased at this cessation of Anglo-Portuguese bickering; the Shah, too, disapproved. Both these monarchs preferred to wage their quarrels by proxy. The Mogul Empire’s internal administration was steadily deteriorating. Company caravans were looted; Company agents were murdered without hope of redress, the reply that the robbers were rebels or Rajputs being deemed adequate defence, whether they were or not. Private trading, always persistent, was now luxuriant. When many employees served for paltry pay or none at all, irregular pickings and the excitement of the possibility of these were the main part of life. Disciplinary action was strongly and openly resented, especially by the seamen.

The Company was doing a considerable carrying trade—doubtfully sanctioned by the Committees, since it enabled Indian merchants to compete, using the Company as wings for transport and protection. When, in June, 1631, a native merchant’s goods are found marked with the Company’s name, we seem to find ourselves peering into Clive’s age. Of course traders wishing to pass their wares under foreign colour would bribe local factors or supervisors to wink at the sleight.

More disturbing yet, Charles and his Parliament were drawing into the long vortex leading to the Niagara of civil war. The King, aware that much of his opponents’ strength was in these upstart London merchants, was unfriendly to the Company. Two vessels, the Roebuck and the grimly misnamed Samaritan, in April, 1635, sailed eastward with his privateering commission. They plundered Surat Indian ships that had Company passes, and a Portuguese ship similarly insured, torturing the captain and crew of the latter to make them reveal their treasure. The French were making their first appearance (as pirates) in Red Sea and East African waters, so that when this news reached India Methwold hoped that the report of his own countrymen’s responsibility would prove false. With characteristic courage he went immediately (April 6, 1636) to the Governor of Surat, whom he found in actual durbar with the chief sufferers:*

‘I found a sad assembly of dejected merchants, some looking through me with eyes sparkling with indignation, others half dead in the sense of their losses; and so I sat a small time with a general silence, until the Governor brake it by enquiring what ships were lately arrived and from whence, what ships of ours were yet abroad and where, and what was become in our opinion of that one ship which we had so many months since reported to expect out of England.’

Methwold’s reply betrayed his ignorance; the Governor

‘told me what had happened about Aden, and instantly produced volumes of letters which did all bear witness that an English ship or pinnace had taken the Tofakee belonging to this port of Surat and more particularly to Merza Mahmud, a known friend to our nation, as also the Mahmudee of Diu. So that now the whole company (which had all this while bit in their anger) mouthed at once a general invective against me and the whole English nation; which continued some time with such a confusion as I knew not to whom to address myself unto to give a reply, until they had run themselves out of breath’.

He and his companion were imprisoned for eight weeks, broken by an interval under surveillance in his own house. The Roebuck was caught by a Company’s ship at the Comoro Islands, July 1636, but handled delicately because of her King’s commission: only part of her booty was recovered.

Charles further gave a charter to a rival group of London merchants, Sir William Courteen’s Association, in 1635. They asserted that this involved no interference with the existing Company’s trade, and that they would not settle where the latter had factories already, a promise which was very casually observed. The inconvenience and loss of prestige to the Company were immense. ‘Squire Courteen’s’ people, ignorant of the rules of the game, did things that incensed the Portuguese afresh; only Methwold’s tact and unfailing courtesy* smoothed the trouble over. It was not until 1657 that the mischievous competition was ended by a union.

Bantam in 1630 lost its primacy to Surat, but for some time longer retained control of the struggling and ill-supported stations on the Coromandel coast. These the Company sought to strengthen. In 1634 they obtained from the King of Golconda the famous ‘Golden Farman’, so named from

‘its bearing “the King’s great seal, impressed upon a leaf of gold”—possibly also with reference to the valuable nature of its contents’*

(though these were summarised by the Bantam President and Council, May 8, 1635, as ‘worthless privileges’ and their agent censured for his extravagance and pomp, ‘two flags and many pikes with pendants, and needless horses, etc.’). The Golconda monarch, ‘of his great love to the valiant and honourable Captain Joyce and all the English’, freely gave ‘that under the shadow of me the King they shall set down at rest and in safety’, an assurance repeated in 1639. Unfortunately, this was not easy to accomplish. A good deal was rotten in the state of Golconda; a typical complaint is this:

‘The loss we have sustained by these Bramons, by unrecoverable debtors fled to their protection, monies exacted from ourselves and servants, and cloth violently taken from our washers, will amount to little less than four thousand pagodas. And all the remedy our often solicitings at court and elsewhere hath procured is a firman lately come down from His Majesty, wherein the chief Kindlers of all these injuries are appointed judges of our cause: the event thereof may easily be conjectured.’*

In 1636, Aurangzeb, a boy of eighteen already deeply hostile to all foreigners, and especially Christians, became Viceroy of the Deccan, and the Mogul Empire’s steady pressure southward began. His siege of Golconda, 1656, failed, but its extinction was achieved in 1687. Farmans from Central Indian kingdoms became worthless.

Bantam was made independent of Surat, 1633, but retained control of the chief Coromandel factory, Masulipatam—where the English, doubly influenced by the Dutch (in its connection with Java, and by the Dutch Company’s presence at Masulipatam and Pulicat), were grossly extravagant and imitated the Hollanders’ overbearing manners. Fortified by instructions from home. Methwold took Coromandel under his own authority, 1636; the East India Company’s affairs in the Malayan Islands become henceforward separate from the purpose of this book.

The famine of 1630 caused a dearth of cloth, the weavers having nearly all died. Bengal, which had escaped lightly, beckoned as the only possible source of supply. From 1630 onwards, there were persistent attempts to establish factories in Orissa and Bengal, to gather up silks and cottons from this one comparatively unravaged region, and to benefit by the abnormal prices of rice, ghi, sugar. The famine thus brought the Company into the coastal trade, since communication from Surat had to be by sea, in the disturbed state of the interior. This began a new peril, and many of their ships fell to the Arab and Maratha pirates of the western shores. Both the Company and Courteen’s Association suffered losses. Small country-built ships—of which by 1640 the Company had many—were in constant peril. A typical disaster occurred in November, 1638, when the Malabar craft were enabled to draw up by reason of a dead calm,

‘insomuch they perceived our ship could not work any way with her sails, they handed their sails and immediately rew all together on board us and lashed fast, notwithstanding we placed ever shot into them and spoiled many of their people. Being lashed on board, they entered their men in abundance, the which we used all means possible to clear; but finding them so resolutely bent, and still encreasing so abundantly, I resolved to blow up our upper deck, and effected it with the loss of not one of our people, yet some hurt, and divers of theirs (namely, the Malabars) slain and maimed. This seemed little or nothing to diminish or quell their courage; but we still continued to defend the opposing enemy by murthering and wounding each other, they being so resolute that they would not step aside from the muzzle of our ordnance when we fired upon them but immediately, being fired, heave in whole buckets of water; insomuch that in the conclusion we were forced to betake ourselves unto the gundeck, upon which we had but two pieces of ordnance. They then cutting with axes the deck over our heads, and hearing the hideous noise and cry of such a multitude, we thought how to contrive a way to send them to their great adorer Beelzebub, which was by firing all our powder at one blast, as many of us as were left alive leaping into the sea, yet intercepted (some) by those divelish hellhounds. We were at that present English 23 (being all wounded, four excepted), blacks 4, and Javaes 4; slain, English 5, Javaes 3, and blacks 13’.*

The factories at Hariharpur in Orissa and Balasore in Bengal, established in 1633, struggled on, until a friendly Mogul Governor appointed Gabriel Boughton, a ship’s surgeon, his medical attendant in 1645. The tradition that this same Boughton in 1636 healed the Emperor’s daughter Jahanara after she had been burned, though mistaken, is old and respectable, as is the story that he asked no reward except trading rights in Bengal for his people. At any rate, he proved a benefactor to his countrymen, winning prestige which he exercised unselfishly.

Not only was the Company building up local traffic in foodstuffs; in the Gulf and Red Sea it entered the coffee trade, and the factors learnt the excellence of this beverage. In this, as in so many good habits, Oxford led the way; ‘a Jew named Jacob opened a coffee-shop in that city in 1649’,* a Greek following suit in Cornhill three years later. The date of the first notified exportation from India is 1658; in 1659 the Dutch East India Company ‘ordered a consignment of coffee for trial, saying that it was beginning to be in demand, especially in England’. The new drink quickly made its way, till the coffee-houses of Dryden’s age took the place of the Mermaid and other famous taverns of Ben Jonson’s age—

‘the Sun,

The Dog, the Triple Tun’.

Another social change began to cast its coming shadow. Pepys, on September 25, 1660, ‘did send for a cup of tee (a China drink) of which I never had drank before’.

The factories were destined to become entrepôts for Far Eastern commodities as well. Peace with Portugal opened up the attractions of the China trade through Macao; and, since England was usually at least in official amity with Holland, and in any case was far stronger at sea than Portugal, the latter country’s nationals found it convenient to send merchandise on East India Company ships. The English could hardly be expected to convey the goods of others past the Dutch prowling and patrolling Malayan seas, without becoming principals in the commerce themselves. Methwold sent an expedition to Macao (April 9, 1635), to bring back gold, pearls, curios, silk, musk, lignum, aloes, camphor, benzoin; and, if there were room, alum, China roots, porcelain, brass, green ginger, sugar and sugar candy. Since the new trade must be carried on in some manner of partnership with the Portuguese, he gave instructions worth quoting as exemplifying the wisdom and tolerance which marked almost all he did. The merchants would get permission to live on shore at Macao, ‘to which purpose you shall take a house, and cohabit lovingly together’:*

‘And that no scandal may be given or taken in point of religion (wherein that nation is very tender) let your exercises of devotion be constant but private, without singing of psalms, which is nowhere permitted unto our nation in the King of Spain’s dominions, except in embassadors’ houses.’

A Chinese document exists, which notes that in 1636 Tour vessels of barbarians with red hair’ arrived from abroad.* In this description we may identify our own countrymen, new to Macao.

Almost from the first, the heads of the factories kept much state. Company employees lived and ate together; there were daily prayers; the President was supposed to admonish the younger members. It is often stated that no capital jurisdiction was exercised, either over Englishmen or foreign dependants; and it is true that each successive commission limited the scope of such jurisdiction by keeping it as strictly as possible to cases of murder and piracy. But the steady accrual of authority to Surat (after the disastrous decade following on the capture of Ormuz and the disgrace of Amboyna), and especially to Methwold himself, was shown as early as October 1636, when the master of the Mary, rather than take disciplinary action himself, reported an offence alleged against an older seaman with a youth. The President and Council went aboard, a table and bar were set up, a jury empanelled, witnesses examined. The man was convicted, and hanged at the yard-arm.*

It had become obvious that the Company must be able to defend life and goods. In 1641, to secure Masulipatam, its earliest settlement on the eastern coast, though the expense aroused the anger of the Court of Committees, the Dutch and Portuguese example of fortification was at last followed. In September a settlement was made at Madraspatam, and St. George’s Fort begun.

Here for the first time the Company acted as de jure as well as de facto rulers. Almost on their arrival they discovered that two pariahs had killed ‘a common whore for her jewels’, throwing the corpse in a river. The deed came to light nearly miraculously, and the local Raja

‘gave us an express command to do justice upon the homicides according to the laws of England; but if we would not, then he would according to the custom of Karnatte’,*

which we may assume was more unpleasant than even that of England.

He asked reasonably, who would come and trade here if report made it a resort of thieves and murderers?

‘Which being so, and unwilling to give away our power to those who are too ready to take it, we did justice on them, and hanged them on a gibbet’,

where they stayed till the Raja’s overlord visited Madras, when the bodies were thoughtfully removed lest the sight mar his pleasure. Eight months later a Portuguese swashbuckler who landed drank too much, and slew one of two Company’s soldiers sent to rescue a Dane he and companions had wounded in seven places. He was not hanged but shot (‘because he pretended to be a gentleman’), despite his people’s indignation at such severity to a hidalgo’s spirited excesses.

In 1647 the Company had twenty-three Indian stations, with ninety employees whose salaries totalled £4700 annually.

The Company had been eyed askance by the King, brushed aside as irrelevant by Parliament. The Civil War launched them on new miseries; the ship of their fortunes dragged through rocky shallows. Their only comfort was that Squire Courteen’s Association had an even grimmer time. War killed the silk demand, and made the home trade precarious in the extreme. The commander of their best ship, the John, delivered it to the King’s navy, so that Eastern seas saw it no more; it preyed on Commonwealth commerce until wrecked. With the loosening of traditional loyalties in England, Company employees grew untrustworthy everywhere; Bengal, especially, bred roguery, and brought trivial profit and mighty anxiety. Private trade proved inextinguishable. It was found advisable to sanction it—first, in such small articles as diamonds, and later, by striving to limit it. After all, sailors have always reckoned to make something for themselves ‘on the side’. Presently Company’s servants were permitted to send home goods, if shipped openly and a percentage paid for carriage and customs and insurance. These privileges proved merely palliatives in the teeming laxity of the times. Repeatedly, when a factor died it was found that he was deep in debt, either to the Company or to country merchants who claimed reimbursement from his employers.

The Company suffered, as we have seen, from the King’s dislike of the London mercantile community. Presently it suffered on an opposing count: after the ruin of his cause the Commonwealth’s thorough-going sequestrations impoverished its Royalist members. When the ‘assault was intended against the City’ the Company’s guns, meant for its ships, were requisitioned by Parliament for defence.

Both belligerents wanted ready money: and both mulcted the Company. The King, buying up their pepper (practically by compulsion), took over £63,000, not a penny of this price being ever paid. Fifteen years later (1655), a windfall came in £85,000 awarded to them by foreign arbitrators, in settlement of their long-drawn-out account with the Dutch, for Amboyna and other wrongs. They were then pressing Cromwell for a new charter and for restraint of interlopers (who had increased during the civil troubles and were some of them in close friendship with the Lord Protector). When the Company incautiously suggested that the £85,000 should be handed over, they were informed that ‘His Highness hath great occasion at present for money’. He borrowed for twelve months £46,000; the twelve months became eternity.

The Company and their more loyal servants could only draw together cautiously, and wait for the long years of national disunion to end. Even this was hard to accomplish; there was growing testiness among the factors, sharp correspondence, demands and assertions of authority by Surat or Batavia, refusals of obedience by inferior agencies. The civil troubles were sedulously made known by the Dutch, who continued to grow to overwhelming superiority and prestige, the English name sinking ever lower. The Company’s ship Endymion was boarded and robbed of her pepper in 1649; and to remonstrance the Dutch commander

‘fell into high terms and swore all Englishmen were rogues and traitors and that he could not esteem them as he had formerly, they having no king; and withal threatened to do the English all the injuries he could, and for the President and Council, he would kick them up and down if they were in his presence’.*

Even the Spaniards and Portuguese recovered a disrespectful demeanour, the offending Adam which had been whipped out of them returning. The entire abandonment of the Eastern trade was a contingency which came close to thought and resolution repeatedly.

The Company had foreseen that the King’s execution would embarrass them with Oriental monarchs. In especial, they feared the Shah would say that the Gombroon arrangement had lapsed, since made between two kings, of whom one was now dead. There is a story that he heard a traveller relate the event as an eye-witness, whereupon he cried out upon him for a traitor who had watched his lord murdered and clapped him in jail. This may be fable; and it is pleasant to know that as late as 1657 some Persians, at any rate, had not heard of the deed (the Dutch must have been culpably slack with their opportunities), for in that year a Persian merchant desiring passage to Surat in an East India Company vessel gave as his reason for preferring this to a Dutch ship, ‘that he took the English for a nation of ancient date, which a King governed (as he said); the other a bad caste, and, though powerful, yet not good’.

In 1649 the safe arrival of no less than seven ships seemed an occasion meriting a banquet of congratulation. A rhyming coxcomb, Francis Lenton, the notorious self-styled ‘Queen’s Poet’, gratuitously offered his tribute. He was awarded £3, which we can only call hush-money, for with it went the note that

‘the Court did not well relish his conceits, and desired him neither to print them nor proceed any further in making verses upon any occasion which may concern the Company’.*

The British connection with India has notoriously been no favourer of literature; but the Company could hardly be expected to welcome bad verses when their world was going wrong.

At last the English in exasperation struck back, in the Navigation Act of 1651, which forbade the bringing of goods into British territory except in English ships manned by a majority of English sailors; an exception was made when goods were of European origin and brought by the ships of the country producing them. This order meant ruin for the Dutch carrying trade.

The Dutch with a persistency that cannot be too admired had pushed unhaltingly forward towards the empire of the whole Asiatic and African seaboard. They had reduced Portugal to the extremity of distress, wresting from her one valuable hold after another, from the Moluccas to Malabar. They spread up the Gulf. Wherever they came they strained all strength to extirpate all trade but their own. Their goods were better than English goods, their home support was firm, their seamanship and shipboard sanitation were excellent, their policy was without hesitations or ruth. That they were universally detested they sensibly ignored as a small matter.

Their news service made them aware (1653) that war had broken out. Keeping this dark, they surprised the Company’s vessels, and sailed exultantly into Indian and Persian ports, their prizes in tow. They swiftly swept English commerce off the seas. Cromwell’s victories in European waters brought only immaterial compensation to set off material loss. Victory in the Channel was a doubtful tale, whereas English shipping captive in the Gulf or in Swally Roads was plain to see.

Meanwhile, the break-up of the Mogul Empire had begun. Bigotry and xenophobia ran through Aurangzeb’s administration, and foreign merchants (most of all the English, whose prestige had sunk so low) endured a waxing arbitrariness of oppression and pillage. Bribes became heavier and more constant, in addition to levies and customs duties. The harassed English looked about for some nook of refuge where their persecuted shipping might hide under the guns of fortification, and their personnel fly for safety. A name that crops up in discussions of what was clearly now a necessity is Bombay.

1657 saw the Company’s fortunes at perhaps their lowest. All through the Commonwealth years interlopers swarmed; another embarrassment was renewed in the sixties—French pirates whose actions sunk into disrepute the general European name. They were followed in 1668 by a French East India Company trading legitimately.

Interlopers at last saw the folly of ruining the whole commerce. Cromwell granted a fresh charter, and the Company and Courteen’s merchants amalgamated and entered on a surly partnership. The new concern bought up the Guinea Company, thereby obtaining gold from Africa and avoiding the drain of specie from England.

The Restoration, 1660, was hailed as setting the Company free from an equivocal position. They needed all the encouragement they could get; they were in controversy with the powerful Mir Jumla, Nawab of Bengal. Madras factors in 1656 had seized a private junk of his, as security for what was apparently a private claim. In the end the Company paid excessively for the alleged loss thus inflicted; and the interim price of his hostility was very heavy. Some madness (worse than ineptitude) was on the Company’s servants in these years. Several of them in 1660 provided the Deccan King with mortars against the celebrated Sivaji. The military prowess of English (still more, of Dutch) troops, and of gunners especially, was well recognised; warring potentates had begun the practice of demanding aid of European science and personnel, English gunners had been lent to the Shah and had kept Aurangzeb out of Kandahar. But the Maratha chief was not the man to forget or overlook a wanton addition to his enemies. Raiding Rajapur, he took its factors prisoners; they languished in hill dungeons until ransomed some years later. Since their misfortune was brought on them by their own action, their superiors, both in Surat and London, were extremely annoyed, and unwilling to pay for their release.

Ceylon was the scene of another bag of English captives in 1660. A ship’s company were enticed ashore and hospitably treated, and then seized. They too spent years in captivity. These were times when Englishmen were lightly regarded, and treated with contempt and unprovoked cruelty.

Chapter III

Era of Consolidation, 1660-1710

Cession of Bombay: Edward Winter: Sir George Oxinden: Sivaji: Second Dutch War: Henry Gary in Bombay: acquisition of Bombay by Company: Gerald Aungier and fortification of Bombay: Restoration in England and effect of Civil War out East: Treaty of Breda: treaty with Sivaji: death of Sivaji: Sir Josiah Child: growth of Bombay: interlopers: rival companies in England: Keigwin’s rebellion: Child’s war with Mogul Empire: Job Charnock and William Hedges: more interlopers: legends of Charnock: foundation of Calcutta: Hamilton the Indian Herodotus: foundation of Fort St. David: execution of Sambhaji: English and Dutch policies compared: rise of French East India Company: penal practice of English settlements; Elihu Yale: piracy: Thomas Pitt: Sir William Norris: peace between rival Companies: Nawab of Carnatic’s interest in Madras: negotiations with Mogul central government: death of Aurangzeb.

In 1662 Charles II married Catherine of Braganza,

‘an event of deep significance to Europeans in the East, for . . . it threw the shield of English protection over the Portuguese, now hard pressed by the Dutch’.*

Rumour rioted; its was obvious that if the English were to implement their new engagements, some harbour must be given them. For a time it was believed that all Portuguese India, or Goa at least, was to change rulers. Ultimately only Bombay (and Tangier) came as the Princess’s dowry.

The Viceroy, passionately supported by his people, flatly refused to hand Bombay over to Sir Abraham Shipman, sent out as Governor. Shipman settled uneasily on Anjidiv (an island fifty miles south of Goa), where he and most of his men died; it was abandoned in 1665. Charles and his Government at length were stirred to such anger that they threatened to demand the Viceroy’s head, as well as an apology. Peremptory orders came from Lisbon; Bombay became British (1665), the Viceroy giving way with this last protest:

‘I confess at the feet of your Majesty that only the obedience I owe your Majesty, as a vassal, could have forced me to this deed, because I foresee the great troubles that from this neighbourhood will result to the Portuguese; and that India will be lost the same day in which the English nation is settled in Bombay.’*

Very much less than what was understood by ‘Bombay’ was handed over, even as it was. The native population seem to have welcomed the departure of the Portuguese, in an address of convincingly sincere irascibility, which singles out their crowning folly of religious persecution:

‘None could with liberty exercise their Religion, but the Roman Catholique; which is wonderful confining with rigorous precepts.’

Many considerations move sympathy for the Portuguese, especially in an Englishman’s mind. But they deserved their eclipse.

Between 1662 and 1665, Sir Edward Winter was Agent at Fort St. George; an energetic man, as his tomb at Battersea witnesses:

‘Thrice twenty mounted Moors he overthrew

Singly on foot; some wounded, some he slew;

Dispersed the rest. What more cou’d Sampson do?’

In that adventure he received a scar that (perhaps intentionally) disfigured his looks and increased his natural extreme tempestuousness.