Crusader’s Coast

With

Illustrations from Sketches

by

C. E. HUGHES

Dedication

Mount Scopus

While the sun, amid blood-red skies, on the Prophet’s Height

Sank from our sight,

Or on Moab Hills the moon rose globed and large,

Like a giant’s targe—

Where the Roman camped, when the darkening heavens grew loud

With the rushing crowd

Of the vulture host that flocked, foul, hard, without pity,

Round the dying city;

Where now grew the fruited vines, and Olivet’s spurs,

With a young wood of firs

Green-fledged, low-murmured as with sough of the sea

And, with rosemary

Sweet-coppiced, scented the evening air as with spice

Out of Paradise;

How have we two, in the fragrant, wonderful hour

When Night, like a flower,

Opened about us, watched the fireflies flitting

Around us sitting,

And laughed at Athene’s owl, all staring-eyed

And ruffled in pride,

As he leaned from his perch in the almond-bush, each horn

As sharp as a thorn!

Preface

I justify this book to myself by saying that it shows what will not be seen again, the Holy Land as it was when the War ended, before progress had laid hands on it. But I know this is not my underlying thought in attempting to give cohesion to what were scattered enthusiasms. That thought is the desire, before too late, to remind any who will read me that Palestine has other than economic values, and that more than one race has rights in it. We hear a great deal of “the poetry of machinery.” Unlike other poetry, this is a kind that man can create at any time and in any quantity. Reading books exultant over the prospect of Gennesareth artificially deepened by many feet and the Dead Sea yielding a hundred tons of nitrates daily, I feel these improvements poor compensation for the loss of the world’s most astounding gulf of fire, the very desolation of savagery. If there can be an Oxford Preservation Trust, whose views are willingly considered by business men proud of their great industrial town, why should there not be a Palestine Preservation Trust, in which even the most fervid Zionist might see a friend and not a foe to his people’s advancement?

Four chapters tell of 1927, not of the War period. I include the story of the Dog River caves after hesitation, hoping that the story may even yet be continued, in which case subsequent explorers’ chance of success will lie in husbanding every ounce of effort and avoiding our mistakes. So here is the record of the men who have tried hitherto.

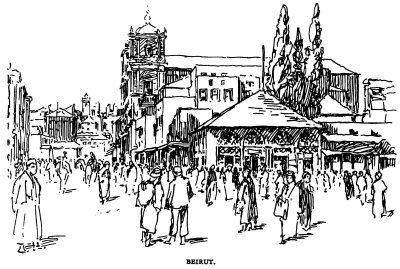

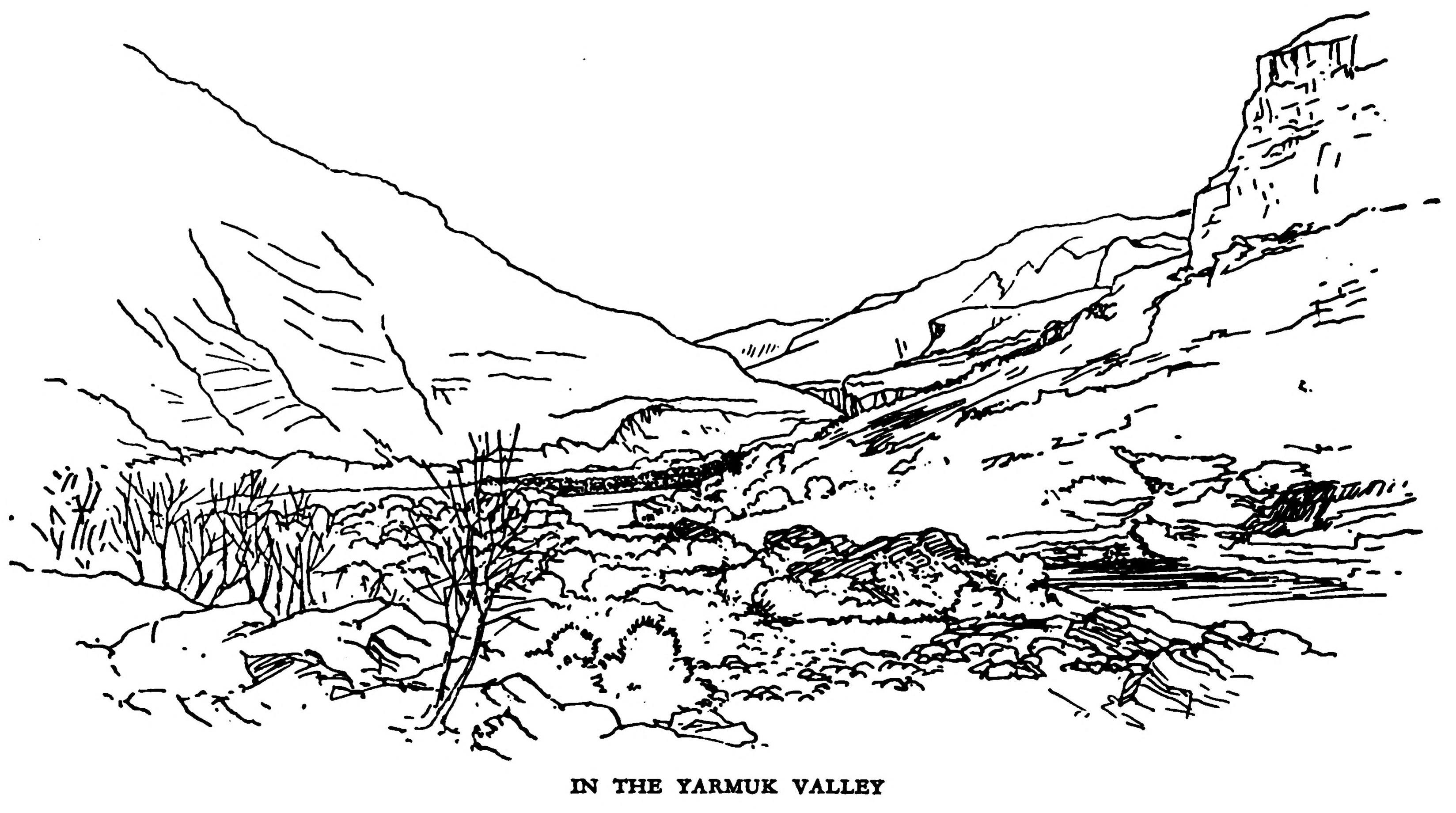

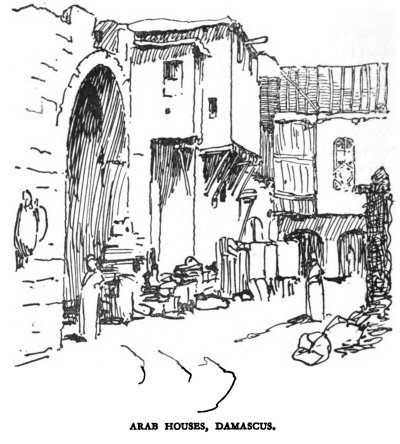

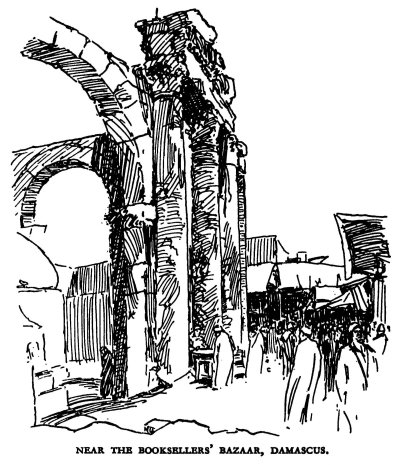

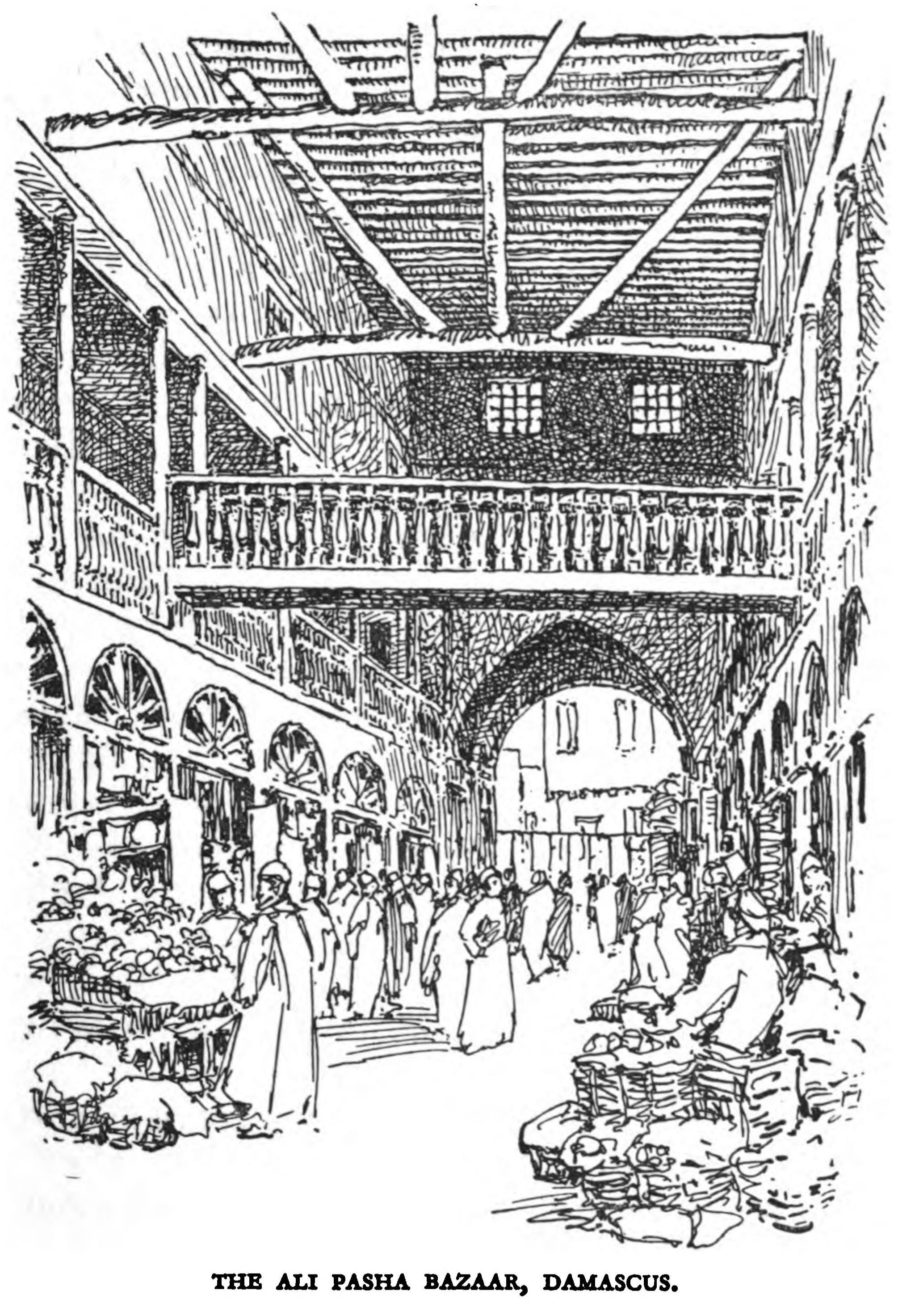

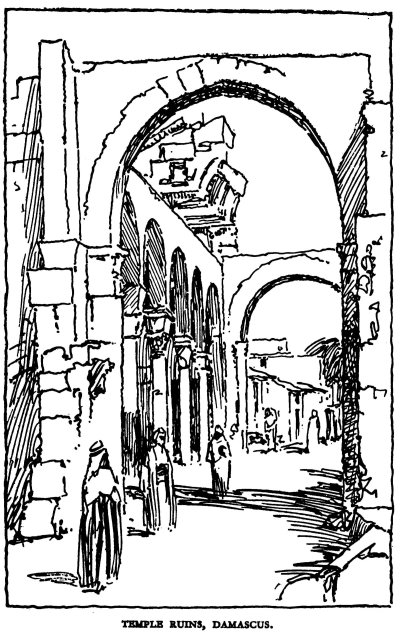

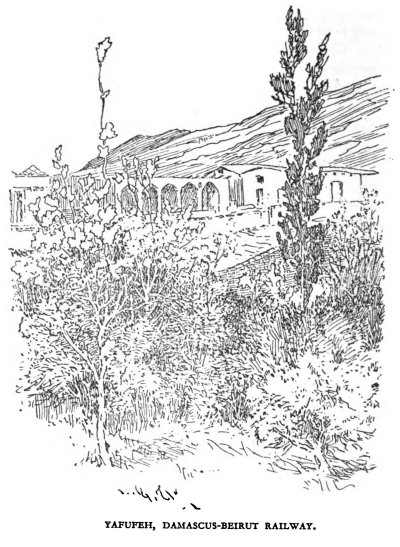

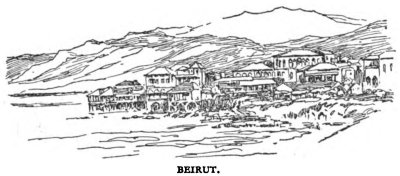

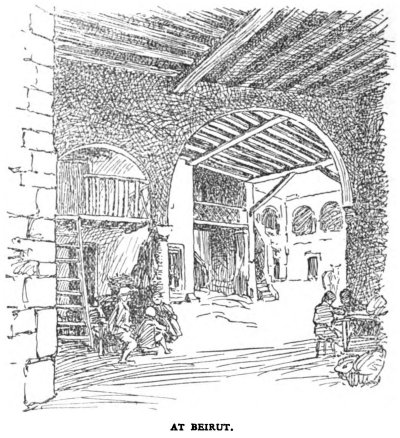

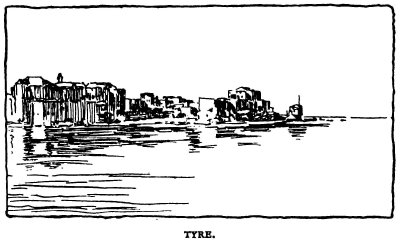

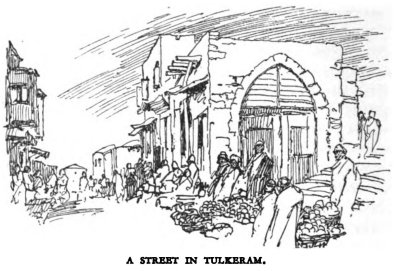

When this book was in Messrs. Benn’s office it was read by one of the directors, Mr. C. E. Hughes. Mr. Hughes showed me his notebooks filled with sketches he had made during a tour in December, 1918, as Intelligence Officer of the East Indies and Egypt Sea Plane Squadron stationed at Port Said. It would be in every sense of the word an impertinence for me to praise these sketches, which his generosity has allowed me to include. But I cannot forbear expressing my admiration for the way in which he has set down both the haunting desolation of the Palestine desert scene and its ruined towns and the vivid and variegated life of that brief period when so many nations commingled in the streets and bazaars of Damascus and Beirut. It is a great loss to me that Mr. Hughes’ experience did not take him over the whole of my ground, but I have accepted with both hands all he could provide, though I knew that the unillustrated tracts of my book must suffer by contrast.

Part of the book’s material has appeared in The Times, Spectator, Sphere, Manchester Guardian, and other papers. Essays on the Jordan Valley and Gilead I have not included.

Oxford, 1929.

I. War Memories

Kantara

They are gathering round

Out of the twilight; over the grey-blue sand,

Shoals of low-jargoning men drift inward to the sound—

The jangle and throb of a piano . . . tum-ti-tum . . .

Drawn by a lamp, they come

Out of the glimmering lines of their tents, over the shuffling sand.O sing us the songs, the songs of our own land,

You warbling ladies in white.

Dimness conceals the hunger in our faces,

This wall of faces risen out of the night,

These eyes that keep their memories of the places

So long beyond their sight.Jaded and gay, the ladies sing; and the chap in brown

Tilts his grey hat; jaunty and lean and pale,

He rattles the keys . . . some actor-bloke from town. . . .

God send you home; and then A long, long trail; I hear you calling me; and Dixieland . . .

Sing slowly . . . now the chorus . . . one by one

We hear them, drink them; till the concert’s done.

Silent, I watch the shadowy mass of soldiers stand.

Silent, they drift away, over the glimmering sand.

The picture is Siegfried Sassoon’s; and of Kantara in April, 1918. The singers and actors were Lena Ashwell’s Party; to whom we owed a great deal in those dead days.

Kantara had an evil reputation. Like the other bases of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, it was reported to harbour a crowd of embusqués. But most of its population was a shifting one, in which every gradation of wretchedness could be studied. Men waited, eternally waited; waited to go up the line, waited for leave or demobilisation. Around were the spreading sands, on whose face this city of tents had arisen. A handful of Olympians lived aloof, the administrative staff who flung orders at us from a distance, while we miserable ones were pitchforked together into huge, amorphous messes. Food was execrable, and was consumed with savage haste, for another horde was waiting; amusements were not, save such an occasional gaff as Sassoon’s verses describe.

At Kantara you caught the faint reverberations of the storm intermittently raging amid Judaean hills, and changed for up the line. You arrived, from England or Salonika or Mespot; you descended at the station, where lorries pounced on your kit and then raced along the dark road with it, scattering their loads at dumps. If you were swift and watchful, and the desert gods had a favour to you, you saw your kit again. Otherwise, you might spend the night, as I did, tramping that stretch of half a dozen miles, not once but repeatedly, raking each dump over piecemeal.

What did they do at Kantara in the Great War? A few played tennis; as a rule, these were residents. For the others, in this unnatural city of the wilderness, life dragged by somehow. New “thinning-out parades” were ever being arranged, and their presence might be called for up the line. Some cultivated castor-oil plants, a congruous garden; except for this useful but unexhilarating shrub, the camp had no green. We cursed the innumerable flies, scrummaged for meals, slept.

Once a group debated those pathetic lines:

The roses round the door

Make me love Mother more.

Why did the poet ascribe this quality to the roses? And one, having been a teacher, quoted Blake’s not less mysterious couplet:

The caterpillar on the leaf

Reminds thee of thy Mother’s grief.

Here, too, was a close connection between human emotion and a vegetable environment; we were referred to an old jest, “What is worse than finding a caterpillar on your plate? Answer: Finding half a caterpillar.” This experience had befallen the mother of the person Blake addressed, and ever after a caterpillar on a lettuce recalled a time of domestic upheaval. Might not this line of approach solve the problem of why the door-clustering roses intensified filial love? But we had a very learned man, who thought otherwise, referring Blake’s “musical and sphinx-like couplet”1 back to old superstition, citing an Anglo-Saxon author who relates how a demon, asked why he had entered a woman, replied with a voice of grievance: “I was sitting on a lettuce, when she bit me.” It was no fault of his; he was but sunning himself on a leaf when his victim swallowed him. At this point heat and boredom closed down the discussion.

After the Armistice Kantara became increasingly a pot of simmering, seething rebellion. Finally it boiled over. In the late spring of 1919 the impossible happened: the British soldier reached the point of mutiny. Meetings took place, where (so people said) the chief orators were not those whose wrong was greatest. Officers were sympathetic, but aloof. Allenby himself had to come and promise that we should be got away more speedily.

I saw Kantara a year later, on my way to India. (I have often seen it since.) This place I had hated more than any I had known. It had changed. Miles of stores, hay, wire, beams, tools still littered the canal banks and the desert. But all that forest of tents had shrunk to scattered groves, and even these were falling before some invisible axe. There had been conflagration, there was waste. Of all that crowded human ant-hill, restless, angry, discontented, only a handful of Indian soldiers remained. Kantara was, Kantara is not. This city in the sands, glaring, unshaded, had played its brief part and belonged to history. The novelist may recreate its unhappy life, but those who wasted dreary days and sleepless nights there will forget it.

In the reed-beds opposite the ruins fires had broken out, now glowing, withdrawn into deep, sullen heart, now towering savagely aloft. Destruction was weaving a dance of death on this body of desolation; Kali, flame-tongued and zoned with darting serpents, as her worshippers picture her in dreadful revel on the prostrate form of Siva, was exulting over man’s departure from her realm.

Crusader’s Coast

We had come from Mesopotamia; three days in Canal sand, at Ismailia, had followed. Then, on the last day of March, 1918, we steamed through fragrant leagues of orange groves and into Ludd Station.

Even without the foil of Mesopotamian memory, initiation into our new campaign had been delightful. The roads were olive-shaded, ditches crammed with English flowers were below the prickly-pear hedges. Though sand, our ancient and hated foe, was not far away and covered the station approaches, its hillocks were planted with figs and black mulberries. We had begun with a long Canal march, wretched with blinding wind and stinging sand. Entrained at last, we noted at dawn a beginning of flowers—yellow broomrape, mats of dwarf stock, tiny white marguerites. And my mind retains a sleepy glimpse of breakers in moonlight at El Arish.

This drowsy, glamorous entry, and the fresh, rain-sprinkled, emerald setting which we reached at Ludd suited the War. The struggles for Gaza and the inchmeal wresting of pass and mountain from the Turk had finished. We were conscious of a slackening of strain, even at the Base. When Maude struck at Kut there was such a tense secrecy over operations that you listened to rumours from the other side of Tigris almost as if afraid of being detected in conspiracy, and you discussed operations little. Here every one spoke freely, as citizen soldiers of Athens might have done. We steamed into Ludd, to find “Fritz” hovering above to inspect us on arrival; but it was a peaceful Fritz, who neither bombed nor spotted for his artillery, but presently sheered off, like a kestrel who has passed a hillside as empty of mice. At the Front we were to find (instead of trenches, with all their apparatus of bays, sap-heads, communication lines) isolated strong points. On some parts of it, if the enemy were unsporting enough to shell us as we lay at ease on our flowery blanket, we dived into ancient tombs.

Every one in the 52nd Division, from whom we took over, impressed upon us, with the air of men anxious to pass on a vital discovery, that the best “Guide” to the country was the Bible, “especially the Old Testament. The whole army is reading it.” “Where does this road lead?” I asked a subaltern on a knoll by the Aujeh. He looked down benevolently and said: “To Jiljilieh. The biblical Gilgal. From the top you can just see Nebi Samwil. The biblical Mizpeh.”

Three days we camped on the Ludd hills, which were still beautiful with the spring flowers. Anemone was finished, tulip was fading. But there were lupins, blue, white, and yellow, a small pink stock, birdsfoot trefoil, mignonettes, mauve vetches, borage, ragged robin and other campions, red clover, cranesbills, germander speedwell, grape-hyacinth, blue iris, aliums of many kinds, Bethlehem stars, marguerites, marigolds, pink bindweed, toadflax, poppies, yellow scabious, sun-rose, an occasional cistus. In dry ditches and open places a tall, many-branched asphodel was common. The Moslem cemetery beside the tower at Ramleh—clustered about with so many crusading memories—was crowded with white spikes of lesser asphodel, the flower of immortality. The ruins of the tower were covered with henbane, whose yellow flowers muffled the arrow-slits and swarmed over the crumbling mortar. The alien cactus made a home for gnarled, grotesque lizards, and a shelter for buttercups, fumitory, campions and campanulas. Bryony sprawled over bush and quarry, broom was ablaze. Of the still richer—far richer—abundance of the hills by Arsuf, a Leicestershire later observed to me: “Here you have every flower that grows in a poor man’s garden at home.” There were other home reminders than the flowers. Larks were singing hard. In the trenches of the fighting just over martins were nesting. The skies were English skies that spluttered with rain. Guns thundered steadily to northward, but we put all thought of them from us till our time came.

That came on April 3rd, when we tramped to Sarona, three miles the other side of Jaffa. This was all artificial country; the roads went between hedges and were bordered with ash, cypress, sycamore, eucalyptus. It stirred no enthusiasm, though it was good to see the groves of lemon and orange and to breathe so fragrant an air. Bethlehem stars grew in myriads, and at a halt the wayside was gold-flecked with a tall sorrel (oxalis cernua). The day was one of tense discomfort, greater than need have been in my case, because of the fact that during the disorder of departure women who had entered our Ludd camp on pretence of selling oranges had salvaged my water-bottle and haversack, the latter containing things of no value to them, but of much to me. Next day I had to retrace my steps as far as Jaffa to purchase substitutes, at Jaffa prices. The villagers round Ludd never paused from marauding, for which later came the terrible but by no means unprovoked punishment of Surafend. As I hope the reader does not know why the Jaffa Surafend became notorious in Palestine, I do not propose to tell him.

To the world Palestine is the land of the Hebrews, but this Sharon coast, except at Jaffa, is a country where they failed to get footing. Its memories are almost all of Phoenician, Greek and Roman, of Crusader and Briton. We were forbidden to call ourselves Crusaders, but many of us were haunted by an older age, and a phantom human tide seemed to be beating southward over these gracious downs. Not ten miles beyond Jaffa is the Nahr el-Aujeh, which may almost be called the Crusader’s River. The tiny scale of Palestine things appears in this fact, that the Jaffa Aujeh, next to Jordan the largest stream in the land, is hardly sixteen miles long. The other chief river of the coast, the Kishon, is twenty-three. The Aujeh is the Old Testament Waters of Raqquon, Geoffrey de Vinsauf’s River of Arsur. After Richard’s defeat of Saladin by Arsuf (Arsur), the Saracens tried to hold the crossing. The story was repeated seven centuries later, with this change, that it was the northern bank that was carried. Where tide and stream have heaped sand and made a ford at the mouth, a stone column even in my time recorded how the Lowland Division (the 52nd) crossed under fire on a dark December night in 1917. Fighting continued till the dominating height of Sheikh Muannis was taken. There was much heroic work preceding the crossing, of swimmers reconnoitring in darkness for fords. Old shell-cases, sunken in lush grass, littered our rugger pitch. I have reason to remember them. After the colonel was sent into hospital I had to supply his place at full back in the match “Officers versus N.C.O.’s.”

We held the line at Arsuf, about three miles north of the Aujeh. The river flows through lovely pastoral country, meadows of campanulas, pink and blue flax, gladiolus, larkspur, lavatera, and scabious. It is a deep stream, with yellow lilies (nymphaea lutea) and, especially at its source, clumps of Syrian papyrus. The only genuinely wild pines in Palestine dot the higher banks of its upper course. Mills and farms of prosperous German pre-War settlements further tamed this wealthy stream, which resembles a larger Cuckmere; just as the Danish dragons could swim with the tide up that Sussex ditch, so here sailing vessels can make their way some miles inland. We were forbidden to bathe in it, for it was reputed to be a haunt of “Bill Harris” (the bilharziosis worm). But we had the sea.

My own brigade spent much time on the Aujeh, as our share of the big push in contemplation was to “seize the fords” of the next river, the Nahr el-Falik. I saw these fords exactly a year later; they averaged 6 inches in depth, and were spanned by a regular service of stepping-stones. The “road” forded the Falik where it had hardly begun to flow; its source was in a thicket of flags, whose drier edges disappeared into massed wildness of brambles, loosestrife, and willowherb. But the sight of our solemn, bearded Sikhs being towed across the Aujeh, sixteen to a raft, and of solitary voyageurs with immense gravity paddling coracles made on the Tigris model is one that I am glad I did not miss.

On April 8th we held our last ford-seizing parade. The push began on the 9th, in the Battle of Tireh. Standing on knolls, we watched the hills which end the Shephelah smoke and thunder and thrust our own preparations on. But the Germans also had a push on in Flanders. So ours, which had gone none too well, was wound up. Troops were drafted rapidly to Europe, the army was “Indianised,” and we settled down to gentlemanly warfare for the summer, with our lines 1,500 yards apart. It will seem strange, but the very casualness of this strife had its trials, and there was truth in a Seaforth’s complaint, that there were “not enough shells to get used to them.” The cliffs were crowned by sand-blown links,2 where men toiled in ones and twos, since they were under observation. Unexploded bombs littered the top of the cliffs, and a superstitious Stokes mortar private, who used to pick them up and throw them over his left shoulder (“for luck”), heedless of whether other men were following him on the ladder-precipitous path from the beach, became unpopular. Inland were glorious stretches of meadow. There was a well, muffled with fig and cactus, which always seemed to hold out offer of a haven—till the guns started. Edmund Candler used to tell of the hatred of war which seized him in Mesopotamia, at the Jebel Hamrin disaster, when he saw men dying, not on the foul, blotched dust, but—for once—among lilies and young green grass. At Arsuf the Seaforths’ colonel spoke to me of the silliness of having to go through “so fair a land in this pagan fashion.” The Arsuf hills—the finish of those Shephelah uplands which are the buttress of Samaria—the first, bright beginnings of Sharon—were clothed with thyme, a perpetual incense in the warm sun, with burnet and cistus, thymelasa, and a thousand flowers. With dusk swift, silent nightjars flushed at your coming, and quails settling for sleep. Brilliant lizards wound through the scrub, snakes were in great number, chameleons and tortoises crawled. The cliffs were narcissus-sprinkled (it was not in flower), and their crest was golden with the profuse blossoms of the recumbent evening primrose (anothera drummondii). Wide patches shone with yellow cup (onosma), and were sweet with a dwarf mignonette, whose chocolate-brown flowers, unlike those of other wild mignonettes, were deliciously fragrant. The campions and clovers were thickened and made succulent by the salt air. Even at the very edge, grass-roots generally fastened the sand together and made a pasture.

Arsuf is one of several places where pagan imagination placed the exposure of Andromeda; M. Clermont-Ganneau derives Arsuf from Reseph, the Phoenician deity whom he identifies with Perseus. The myth travelled to Lydda (Ludd), where Perseus became St. George; and from Ludd, mainly by the Lionheart’s influence, Perseus and his dragon walked on to English coins. Marble columns cumbered the pebbles of Arsuf’s ruined harbour, that had been Phoenician first, and glimmered under clear, green water. A curve of the lofty coast sheltered bathers from all but a preternaturally lucky hit. Nevertheless, the enemy gunners used to try to catch our bathing parties—a shabby trick, since we could not retaliate against troops who did not bathe. But the long perfect beaches and the sun would have tempted us successfully had the danger been many times greater. In earlier days authority had occasionally held out the menace of sharks. There was a time when the Worcestershire Yeomanry, expectant of relief after weeks of warfare before Gaza, heard the mess-tent telephone bell, and the officers rushed up in a body to be in at the news. It was this: “It is reported that sharks have been seen off the coast. The greatest care will be exercised by all units when bathing.” The reply was indignant and extempore: “It is reported that rhinoceroses have been seen in the long grass of the Wadi Ghuzzeh. The greatest care will be exercised by all units when going to draw rations.” Nevertheless, though I have been anchored for days off Muscat and know well the seas between Rangoon and Suez, the only living shark I have ever seen was basking on the surface just outside Alexandria Harbour.

Four hundred yards back from Arsuf Harbour was a small hamlet, Haram Ali, which the Turk plastered regularly. It owns a patron saint, in his lifetime remarkable for skill in catching cannonballs. His ghost had opportunity for plenty of practice now. Another point greatly vexed by our enemies was Bedouin’s Knoll, beyond Arsuf. At first this was scrapped for nightly, since it gave observation during the day. (The enemy captured our best three-quarter in one of these little tussles.) Then it passed into our permanent possession. These points of divided occupation were a feature of the Holy Land war. Before Gaza there were “post offices,” ours by day, the Turk’s by night. Here we left newspapers and especially photographs of Turkish prisoners selected for their fatness and posed behind tables loaded with food. Our leaders attached great importance to these photographs as a means of winning the War; men had to crawl up to the enemy wire to leave them there.

There was many a bloody scuffle in the marguerites and poppies before both sides settled down for the summer. Two savage little affairs in June secured Brown Ridge and the Sisters, undulations which gave us all the ground observation and (an essential and carefully thought-out part of the scheme) pushed the Turk into the malaria belt of the Falik swamps. The earlier battle was made picturesque by little mobs of Turks rushing without direction through the nullahs, shouting “Allah!” This was understood to be a counter-attack, but it came somewhat late.

Our assault was so complete a surprise that the enemy signallers in their forward dug-outs pretended to be asleep. “Shall I stick them?” asked a Leicestershire private of his second-lieutenant. The answer was a nod. Prisoners’ bread was analysed by the Leicestershires’ doctor, who reported that the rolls were made of straw, with mud as the binding material. One prisoner was so absurdly like a renowned company commander that he was kept back after his fellows had been sent down to the Base, that all his double’s friends might have a chance of seeing him.

The habit of raiding grew on our troops, and the Sikhs were particularly adept at it. When in the autumn Allenby broke through, the enemy had become very wretched. One terrible mishap marred the triumphant race north, when the Seaforths were thrown, without artillery support, at Beit Lidd, a steep slope crowned with a cactus-ringed village and set in terraces. As this was the end of the War, no less than six M.C.’s came to the battalion, one—contrary to the M.C. rule—a posthumous one. The first fortnight of October saw the Leicestershires swinging through Beirut, just as they had marched through Baghdad, nearly a twelvemonth before, when leaving Mesopotamia. While the populace showered garlands on them and cheered madly what most supposed was the British National Anthem, the short, stocky figures chanted the lovely chorus:

Roly-poly, treacle duff!

Roly-poly, that’s the stuff

Oh, when I think abaht it it makes my tummy ache!

Oh, lor lumme, I want my mummy, the pudden she useter make!

Arsuf, after its brief and partial emergence into the upper light of history, has sunk back to its pastoral obscurity. Yet tourist and archeologist, wandering through even this land, so wealthy in sites, cannot altogether neglect a place where sea and shore hold so many relics, from so many times and peoples. There is the tiny harbour, used by Tyrian and Briton so diversely. The masonry is studded with arsurines, green and blue stones, and great quantities of coloured glass, melted in some conflagration or abandoned from what was perhaps an ancient glass factory. Recumbent pillars are set in the steps which lead up the cliff. Pottery in abundance strews the earth, some of it glazed, and much of it very old. At the cliff top are ruins—the castle which repulsed Raymond of Toulouse and Godfrey himself in the First Crusade, and later was a bulwark against the Moslem surge, when Christian lords held this coast and Islam was wresting the last strongholds one by one back. Vaults and masonry, that served us for makeshift trenches, are overgrown with datura and scrub; when I last went over them, in 1919, a wild cat leapt out. Will the archaeologist of later ages, examining pillars and tumbled castle, think of us who burrowed in rock-tombs and hid in caves at the cliff root while the 5.9’s rapped on the flowery pastures overhead? Or see, in his rekindled vision of the past, not only Phoenician trader and Roman galley and Frankish war-sloop seeking this mimic haven, but our vanished sojourn also? See the colonel and second-in-command of a famous regiment whiling away afternoons of little employment by gathering against each other cowries, dug out of the sands? Figures walking over the breakwater, stunning fish with rifle-shots? Stealthy patrols scattering in the dusk? Jubilant crowds exultant in the surf and laughing when a chance shell screamed far out to sea, bouncing up a column of spray? For this, too, is now history and will one day be ancient.

Yellow Sorrel

When we marched out of Jaffa, the way

Was bordered with sorrel

(Tall, long-stalked, beautiful, gold-flowered sorrel),

Which made the land gay.

But we raised no Te Deum,

Because of the day,

Which was hot, as we trudged

And dustily drudged,

While the weight of our packs

Sent the sweat down our backs.Two miles out of town,

At the halt, we flung down,

And oranges sucked

And listlessly chucked

The peel at the view;

Then went on through the sorrel,

The marvellous sorrel.The colonel described

That patch at our side;

He liked flowers, and knew

Quite a little about them,

But the glance that he threw

Said, “I’ll manage without them.”

And Irishman Mac

Held, unseeing, the track

Past fields that would stock

The whole world with shamrock.

And Keely displayed

No great joy, I’m afraid.

And I dare bet G. A.

Didn’t know what was there.

And Mason and Thorp

Gave never a stare.

On our brows the beads glistened,

As we lifelessly listened

To the guns that we neared;

So we washed out the sorrel.

For Jacko, we feared

(With whom we’d a quarrel),

Cared nix for the sorrel,

Just nix for the sorrel,

The gold-flowered, beautiful, tall, drooping sorrel.

Jerusalem: War Memories

For me Jerusalem has such a spell that, though I head this essay with its name, I hesitate to begin on the theme, but wander round its walls, and would stand where the hills have a less august story and memories less austere. There are its approaches, the defiles of Samson’s country, through which you pass from Ramleh to the Holy City; stony heights, shagged with coarse grass and scrub and, above all, with thymes and thistles. No land has a greater abundance and variety of thistles and thymes and mints than Palestine, and their tribes flower all the year round. The deep Judaean wadis, no less than Carmel and Tabor, are coppiced with oak, carob, terebinth, lentisk, arbutus, bay, styrax, hawthorn, broom, cistus, salvia. Honeysuckle grows in the ravines round Nebi Samwil. But the summits and slopes are bare.

Partridges bring off large broods in the dry bottoms. Till recent days the hunting leopard laired in some of the limestone caves. Hares, gazelles, hyenas, foxes, wolves—all find shelter amid the rocks and screes. Porcupines have their holes in the hillside. They were sufficiently common, a little farther south, in the time of our warfare before Gaza, for some to find them a pleasant change of diet. A friend3 had an adventure with one near Ludd, when Authority, learning that his life had been spent in digging (he was an archaeologist), put him in charge of road-making. Surface material being bad, he entered a rock-tomb to see if there were better stone beneath. Crawling out through the narrow opening he heard his Greek foreman shout, then laugh loudly; the light was blocked, and a body dashed into him. This newcomer, failing to get past, tried to reverse, hurting horribly; failing in this also, it rushed forward again, and by its rival’s accommodation got through, and ran over a pile of rubble into a hole at the back of the tomb. Engelbach came out and found his shoulder bleeding, full of quills.

Overlooking Jerusalem is Nebi Samwil, Mizpeh, the Crusaders’ Mont-Joie, from which they first saw Jerusalem. From this peak our own men, whom, by special and often-repeated routine orders, it was forbidden to call Crusaders, saw the Holy City through terrific days when shells hurtled to and fro from Mizpeh and Olivet. Jerusalem herself, so often sacked and ruined, escaped the ravage of battle, “her warfare accomplished” at last. But her incomings and outgoings suffered. The Ophthalmic Hospital and the pine woods of the German colony, on the road from Bethlehem to the Jaffa Gate, bore marks of shell and bullet. On Nebi Samwil the hostile lines were in places not 40 yards apart, and there was bitter clashing. The mosque of Samuel’s tomb was shattered, and behind stone walls and sangars swiftly hurled together remained signs of those hard days, tins and rotting clothing.

Bittir, Bethel, Ai, Gibeon, and a host more—of these let the commentators speak. We of the Expeditionary Force were there as pilgrims and sojourners in the land, expecting till the autumn push came. We dwelt in camps and billets, or in the two hotels, one of which, the Fast, found fame in the pages of Punch by the legend after its name, “Visitors must bring their own rations.” We made our multitude of roads for military traffic, with side-tracks bearing where they diverged from the main way the tactfully-worded notice: “Horses, mules, camels, donkeys, civilians.” Corps occupied the German hospice on Olivet, famed for its singular mural and roof decorations, the Kaiser as King David and that other of the Kaiserin receiving from her lord a model of the building—“Here’s a Noah’s Ark for Little Willie.” We had our cricket on Olivet, matting on a good true pitch, but an execrable outfield, a chaos of boulders and thistles. Here many world-renowned players performed. Afterwards Corps would entertain the teams, and there would be a “gaff” to follow.

Bethlehem, to those who care to see, gives a notion of what even this stony land has been. The hillsides are wooded with olive and pomegranate, a pleasant front of verdure. Looking down on the Shepherds’ Fields, and across to the mountains of Moab, you feel the fascination of the contours of these gaunt highlands. The land is naked and old, but not yet haggard.4 When the moonlight floods them, the hills are lovelier than an angel’s dream. David’s Well is fern-fringed. Wherever there is a crack which rigidly excludes the sun’s rays, maidenhair grows; alike at the lip of David’s Well, and in the Kedron tomb-caves and on shelves in the limestone beside the way from Gethsemane to the Damascus Gate.

Further afield is Hebron, noted yet for its grapes; noted, too, for the fanaticism of its Moslem inhabitants, in this particular second only to those of Nablus. The mosque over the Patriarchs’ tombs, in pre-War days opened to only a handful of exalted Christians, during the War was entered by a fair number, under permit from the Military Governor. But Jews were not permitted even to the door. They could go to a certain step, where there is a crack in the wall, through which his despised descendants precipitated letters to Father Abraham, in whose honour his children’s enemies kept this shrine.

At Hebron is the pool where David hanged the murderers of Ishbosheth, a brown, sinister tank. At Hebron, also, is the noble oak named of Mamre. The Hebron country has other fine oaks, and an abundance of shrubs that, if goats could be kept off them, would soon change the face of the district. On the Judaean hills, even round Jerusalem, wild roses grow; but it would be hard to prove that they ever flower. They are like the Epping Forest lilies of the valley. But near Hebron I found, in early April, 1919, a bank which was one riot of wild roses.

Where tradition puts the Baptist’s home is Ain-Karim, four miles out from Jerusalem, in a delightful vale, fed by a spring of plentiful water. I remember an amusing half-hour here, on an evening of quiet, clear sunlight, when I watched a fox fooling a village dog. The hillside was stone-terraced for vines. The fox would wait till his clumsy pursuer, barking and jumping heavily along, almost reached him, then he would slide down the wall into the next field. The dog would go round noisily to the lower allotment, not being able to slip down the wall. The fox would behave as before. This game went on for a considerable time, till the dog gave it up and trotted away, the fox looking after him.

Evening and the throng round Ain-Karim fountain, the good temper and the flashing, musical waters, the sunlight and gentle green of the pennywort springing from the stone walls, the fringe of colour trailed alone the hedgerows, of poppies and fumitory, mallows, cranesbills, henbane, ranunculus, wild garlics—“ver’ ordinar’ flowers,” as a Syrian observed to me on Carmel, weeds of no great note, but such as the good God scatters everywhere on the waste ground; all this was a sight calculated to make a man love his kind. And above were the hills, so stony and with so many bare patches, yet with such an appealing loveliness when the mind has dwelt with them—a heath of aromatic scrub, shot with radiance in spring, and even in the heats of summer keeping gold of flax and thistles and the varied purples and reds of the wild mints. In October, the heart of the mountains blossoms. Who could have guessed what tenderness had slept the summer through, folded deep under parched soil and hidden in clefts of rock? With the first gentle rains blue squills appear, and saffron crocus; cyclamens thrust up their leaves, whose underside is so lovely in its veined purple that we can well wait for the flowers. The true crocuses follow, blue and white. Then in a great wave spring overspreads the hills, even these hills of Judaea. By May the tide has ebbed, and of the lilies only yellow asphodeline remains. But mints and thymes and thistles continue. In July, Mr. Dinsmore, of the American Colony, took me to a hillside just outside Jerusalem, and showed me a little enclave made by the moor-gods, a fairy corrie where grew rosa canina, though so dwarf and trailing as to be overlooked except by careful search, styrax, wild olive, oak, terebinth, and a dozen thymes in flower.

The hillsides, to complete their picture, need this addition, that, scattered widely, a shrub or tree rises; carob as big as an apple tree, struggling oak no taller than a privet, or hawthorn cowering close to the wind-swept slope like a humpbacked dwarf.

I suppose one should speak of Bethany. But that huddle of houses beside the dust-tormented road interested me most because I found the words of Karshish true:

Blue-flowering borage, the Aleppo sort,

Aboundeth, very nitrous.

Borage is no rarity. It carpets Olivet; and the stones of the Temple courtyard are one tangle of it in many places, especially under the great olives.

After Allenby’s entry Jerusalem was at peace. The city was too sacred for hostile aeroplanes even to appear over it. But the War was at her borders, and the guns could still be heard. The fields to the north, on the Nablus road, were strewn with relics of conflict. At Ramallah a boy was brought before the Military Governor, charged with bomb-throwing. His defence was that he found lots of these round things, and once, when his sheep were loitering, he threw one at them, with splendid result. It made a big noise, and they hustled home. Since then, he had searched diligently for these crackers, and whenever his sheep were laggard encouraged them with a grenade. This pleasing yarn suggests a rewriting of Southey’s “Battle of Blenheim,” with Peterkin bringing duds to the appalled veteran:

He came to ask what he had found That was so large, and smooth, and round.

The City

The many bad books on Jerusalem have confused men’s minds with weariness of a place which its praisers have nowise helped others to see. I need not say that I do not write thus of Sir George Adam Smith’s two noble volumes, my daily companions as I searched the walls and streets, the pools above and the “waters that are under the earth”—a large part, these last, of the city’s life and story. There is always something fresh to see in Jerusalem. Yet, as the place sinks deep into imagination and grips the heart, it becomes ever harder to speak or write convincingly concerning it.

Of the Holy Sepulchre every traveller’s book speaks. But it is only with residence that you learn how varied an appeal lies in each yard of its neglected environs. There can be no other place where you so feel what Father Tyrrell rejoiced to know, the welling up of the sap in your veins from the hidden roots of the tree of humanity. For example, take a spot within 100 yards of the Sepulchre, visible from shops in Christian Street—“Hezekiah’s Pool,” the Κολνμβήφρα Ἀμυγδαλόν, the “Bathing-Place of the Almond Trees”5 of Josephus. From this shrunken puddle came light on an experience in Egypt. At Assuan, my dragoman always spoke of the ruined Roman baths in the Nile as “Queen Kolubetra’s Baths.” Kolubetra seemed obviously Cleopatra. But when I wished to find out if perchance the native pronunciation of the name of the “serpent of old Nile” had been Kolubetra (since the Arab makes our “p” into “b”),6 all he would say was, as before, they were Kolubetra’s Baths, always had been. Other names he pronounced as the books had taught him—in the main. In Jerusalem, the puzzle cleared itself, as I was looking out from the tailor’s shop on the “ Bath of the Almond Trees.” Kolubetra was Κολνμβήφρα and “Queen Kolubetra’s Baths” were really “Queen Bath’s Baths.” So here to-day in Upper Egypt a Greek term had survived the centuries, helped by sound-confusion with Cleopatra, and was extant in the patter of a dragoman.

Jerusalem’s countless visitors carried away the pleasantest impressions, as a rule, not from the Sepulchre but from the Haram and the Church of the Ecce Homo. The latter, a recent church, scarcely half a century old, had everything in exquisite simplicity. The Sisters of Zion, who have the charge of it, are unwearied in their courtesy to the never-ceasing parties of visitors. Their church, in addition to the side-arch about which it is built, contains a tribunal, and part of the scarp of Bezetha, the New Town, here cut down for the moat of the castle of Antonia. In the same buildings are another tribunal; and one of the most moving sights in Jerusalem, the old pavement. Here are squares and circles, scratched by Roman soldiers for their games of chance, while tedious business was proceeding within the Prastorium—trial of a prisoner or the handling of an excited deputation. In the same darkened vault and on the same pavement are stones roughened for passage of horses, and pious hands have placed a Figure staggering under a cross.

The War gave these Sisters an opportunity to attempt what has been done so often, to deflect the stream of tradition. The first Station of the Cross had been in the Turkish barracks opposite. As these were closed, the Sisters insisted that the first Station should be here. Their attempt was made in good faith and with more show of reason than most such attempts have had. But they had formidable competitors in the Greek hospice next door. Here are great underground dungeons, rock-hewn chambers, indescribably miserable, a nightmare to enter even as free men. The chambers have peepholes for the sentries, and some have stocks cut in the stone. Imagination is oppressed as it visualises the deeds done here, and one “hopes there is a Hell.” It may have been here that Barabbas sat, with expectation of no other escape than to the death of the cross. Within are pits crammed with human bones.7

The Haram brings the mind closer to our Lord’s life than any other site in Jerusalem. Not least, it lies open to the free wind and sun, and you can understand how it was that He was able to look up into a cloudless heaven and the face of a Father. All is friendly here, from the circling pigeons to the grass which knits the flags. In the lower courtyard are the kindly grey trees, old olives with their arms crowded with mistletoe. No tree, not even the apple, carries more mistletoe than the olive—the groves in the Kedron valley are prolific of it. Here, in the Temple court-yard, the olives have their feet tangled in grass and thistles and borage. So it must have been in Christ’s time, and the flowers and wealthy bushes spake of His Father’s business and His, to bring life abundantly, while men destroyed. That flower of Jerusalem walls, the snapdragon, is rooted here in the battlements. I never saw it without remembering Newman’s walls at Oriel. And there is the caperbush, the “hyssop that springeth out of the wall,” brightening the stones with its white, spraying blossoms. And there are the tall cypresses. And, opposite, the tombs and spaces of Olivet. Here He walked when Galilee was a memory, resolutely flung behind Him, and storms were gathering for the finish. Under the olives and among the thronging crowds He found His Father, and left what we should call the Temple to formalist and bigot.

The Aksa mosque, where two of the murderers of Thomas à Becket are buried, has a place where the guides and Moslem guardians tell you that Zacharias, the father of the Baptist, “prayed”— or, rather, “brayed.” See the genuine tradition here of another Zacharias, “the son of Barachias,” whom they “slew between the temple (walls) and the altar.” To this place Christ pointed, and emphasised His warning of destruction at hand.

The Haram area is a museum of architectural styles. In the Dome of the Rock are things beyond all praise, such as the glorious roof and the ironwork left by the Crusaders. At this place through millenniums worship has been made, history has been enacted. Primitive animism, Araunah’s threshing floor, Solomon’s glory, centuries of bloody sacrifice, sacrilege of Antiochus and Pompey, patronage of Herod, the terror and horror of the Roman siege, the agony of the Crusaders’ storm, ritual of pagan and Jew and Christian and Moslem—these are but a few of the associations of this bare rock, assuredly a hallowed place, if human passion and devotion can hallow any place. Yet, for all that, for those who follow “the Lord of all good life,” the deepest sanctity of the Temple area is away from the rock, in the courts outside. “Without the city wall” are spots more sacred still. Somewhere on these limestone hills He died; in that stony torrent-bed He passed nights darkened and in solitude of spirit, but assuredly, if one may so lift a pagan’s gay egoism to loftier purport, non sine dis.

This is how to secure the most wonderful and interest-crammed hour the whole world can give you. From the Jaffa Gate, where the early markets and shop-booths are, pass down the Hebron road. Above you are the massive buttresses, surnamed of David, supposed of Herod—his tower of Phasaelus. Swifts are flying in the afternoon brightness, the crowding life of the desert is entering in through the gate. Forget all later memories—the Turkish gallowstree, the Prussian warlord’s pomp, our own troops and their leader. You are to plunge into the far past. As you descend, Zion, the false Zion of tradition, rises high on your left. Here the earliest Church had its home, here the Virgin Mother died. Where the first descent has finished, and the road levels ere it rises, is the pool called the Birket es-Sultan. Yes, there was always an embankment there. Remember how clearly George Adam Smith brings out Jerusalem’s persistent efforts to draw all waters within herself, and to slay her foes with drought. You turn to the left, down the Wadi er-Rababi, the Valley of Hinnom. At its beginning notice the well-grown hawthorn. Below you are others. Spring by spring they flower, but their beauty is grimed and dim, for there is always a dust cloud dancing on that busy road which you have just left. A short ravine, dark with olives and the shadow of steep hills, brings you to where the valleys of Hinnom and Jehosaphat meet. About this region cluster the sinister memories of Jerusalem. Here were children passed through the fire to Moloch, here King Ahaz, shrinking before the menace of Assyria, sacrificed his son. By that ruined well, Job’s Well to-day (En-Rogel of the Old Testament), Isaiah, within sight of the place of that dreadful immolation, met the faintheart king with the great Messianic prophecy. To En-Rogel Joab brought Adonijah for coronation. Down on En-Rogel Aceldama looks. Beyond En-Rogel, Hinnom and Jehosaphat continue in the Wadi en-Nar, the Valley of Fire, a burnt ravine running down to the Dead Sea. In Moslem legend, the Valley of Fire is the home of Asrael, Angel of Death.

At Hinnom’s end, you turn sharply to the left. You pass upward by a very gradual ascent. Opposite is the Hill of Offence, traditionally the scene of Solomon’s idolatries. On its lower slopes are the houses of Siloam, whose inhabitants are troglodytes, with their homes built against caves and rock-tombs. Below are the King’s Gardens, the gardens of Siloam, fed by “the waters of Shiloah that go softly,”

Siloa’s brook, that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God.

From your left the Tyropoean Valley enters, almost filled up with rubbish. In its mouth grows an old black mulberry, the traditional site of Isaiah’s martyrdom. Fifty yards up the Tyropoean is the Pool of Siloam, a minaret above it. The Pool has been narrowly circumscribed by Herod’s and later masonry, and is a shallow, leech-infested water. Into it Hezekiah’s conduit, a dark gallery cut through the shoulder of the hill, brings a racing stream when the Virgin’s Spring flushes.

Continue up the Valley of Jehosaphat, climbing over the rubbish of ages. Flocks of goldfinches rise, as you push through the thistles; a gnarled, thorn-hued chameleon crawls away. The tombs begin. Presently, both sides of the valley are one vast burial ground. From the tombs, and indeed everywhere, till the hillside is one bulbous outgrowth, spring the lilies that lift the tall white spikes, urginea maritima. Josephus, describing the agony of the siege of Jerusalem, tells us how ravenous mobs in the dead of night crept into this valley to gather roots. The Romans set ambushes for them, and crucified those they caught. If some returned safely, often the city guards robbed them of their wretched food. These lilies, I think, were the roots they sought.

Here is the Virgin’s Spring, Gihon of the Old Testament. Steps lead down to it. The water floods from a siphon-spring in the rock into this channel. Once the overflow went into the valley, but Hezekiah “stopped the brook that ran through the midst of the land, saying, Why should the kings of Assyria come, and find much water?” On the tongue of rock above stood the primitive hamlet of the Jebusites, with a shaft sunk through to this channel (whose beginning is older than the rest). This was where David was mocked by the too confident defenders, till Joab stormed it, by way of “the gutter” (whatever that was). On this ridge probably stood the Akra, whose alien garrison so long defied the Maccabees. They had access to the one perennial spring of Jerusalem, and below them were the rich gardens of Siloam, inhabited by a population unfriendly to the Jews. To this eyrie food could be smuggled from the valley; and from this vantage they could harass the Temple worshippers. There, above you, is the Temple area, with the jutting point from which tradition says James the Just was hurled. From this ravine, polluted through all ages, where once the loathsome worm that died not crawled on the festering remains of criminals, and where the smouldering fires in never-consumed garbage were not quenched, Dives in the Parable looked up at Lazarus in Abraham’s Bosom. There is hardly any herbage here; only the thistles and the lily of desolation and the squirting cucumber, whose useless fruit bursts in the hand. You cross the valley to the opposite ascent. The path passes beneath rock-tombs, almost certainly here in Christ’s time. That queer building, with a great hole in it and a heap of pebbles round its base, is known as Absalom’s Tomb, at which Jews cast their stones. The path climbs between stone walls, where tall mulleins stand up like many-branched golden candlesticks; and you are on the Jericho road. A short distance brings you to the Virgin’s Tomb—also grave of the scandalous Queen Millicent. Beside this fine Crusader church, which is now far below the level of the ground, is the Grotto of the Agony, a cave whose simplicity is welcome. The Franciscans’ Gethsemane is 100 yards to your right, where you may see the old olives and be given a handful of flowers and sprigs of rosemary, “for remembrance.” Rosemary abounds on Olivet.

The road turns sharply to the left, crosses the dry Kedron, and turns right again by the shelter erected in honour of St. Stephen. Here a steep climb begins. But first, notice these rough relics of steps cut in the limestone. For a marvel, no Church has appropriated them or defaced them with a shrine. Yet it is hardly doubtful that by these steps Jesus descended from the Temple to the olive-groves.8 Here are large zizyphs, the tree from which tradition makes the Crown of Thorns. These yawning cracks by the wayside are lined with luxuriant maidenhair. Near the top of the slope a short path between banks of rubbish and cactus hedges leads to St. Stephen’s Gate. Inside is the old Crusader Church of St. Anne, which Saladin made a Moslem theological school and which covers the supposed Pool of Bethesda, now being excavated. You will find a Roman pillar there, with a floriated capital, and a notice “Piscine Probatique.”9 But return to the main road. It turns to left again, and runs directly beneath the noble walls. Nowhere do the walls show to more impressive advantage. In five minutes you reach Herod’s Gate. It was near this spot that Godfrey of Boulogne mounted his ladder, and first of the Crusaders entered the city. These banks, which only half cover the remains of Herod’s wall, are a great place for glow-worms. In this part of the city took place that memorable streaming-away, when from sunrise to sunset the poor escaped through the postern of St. Lazarus, permitted by Saladin, after the fall of Jerusalem, to depart without ransom.

A short distance further, and you pass the huge grottoes named Jeremiah’s, and the eyeless sockets in the limestone hillock which Conder and General Gordon thought was “the Place of a Skull.” Certainly here tradition sets the common place of execution, and the earliest tradition puts the death of Stephen near by. Almost opposite are the far-stretching caves beneath the city, called Solomon’s Quarries. A little further, and you are at the Damascus Gate, where you may see the arch of Herod Agrippa’s second wall. Here the street El-Wad runs into the heart of the city, over the course of the Tyropoean Valley. This, if followed, will bring you to the Via Dolorosa, and the old Cotton Merchants’ Market, ten years ago a deserted vaulted bazaar. The economic centre of Jerusalem had moved to the Jaffa Gate and the west. The British occupation so cleansed the city’s foulness that few would believe how unspeakable this once crowded mart had become. Streets entering El-Wad lead in a few minutes to the Haram, the Praetorium sites, or the Holy Sepulchre. How widely we have travelled in an hour!

Her visitors are conscious enough of how bigotry and cynicism have soiled the noblest city of the world; and her sordid greed is open to view. But I would forget all this, and would remember, as I close, only her gracious story, and the hills which girdle her, the lights of heaven which make her glorious. I would see again the wonderful contours of the bare heights, or look down from Olivet on Jordan, the perpetual haze of heat and damp in which our soldiers endured days never borne before. Who that has seen can forget the fascination of that view? The battlemented crags beyond, the seething trench, the darker green of Jordan’s rankness—“the Pride” or “Swelling of Jordan,”—the black tongues of the river’s delta, the steel-blue of that sunken sea? I remember the groves of fig and olive in Kedron’s upper cleft, where Athene’s owls sat in glaring sunlight or flitted into shadow of the rock-tombs. There lies Olivet, with its dense growth of thistles, the golden and the larger purple, its yellow flax and restharrow, its borage, and in autumn its grace of tender lilies. Midway to the pinewoods and vineyards of Scopus lies the cemetery made for our valiant dead, whom shell and bullet or fever or the serpents by Jordan slew. Yellow flax made this patch its home, and spread “a light of laughing flowers” over the like a benediction. I remember evening, and a crescent moon set in a sky green with the afterglow of summer sunset. Then there was the first coming of the rains, the first autumnal eve. First, the red shadow of sunset on Olivet’s upper slopes, and vast cloud-crags in heaven. Following, a sky of silver-grey blue dimness, over grey olives, grey boulders, grey tombstones. Last of all, a most magical moon, full and glowing, the deepest orange. It is with night that Jerusalem wakes to her full loveliness, and remembers how kings desired her and the thoughts of all nations have turned to her. Nights have I known of moonlight flooding the walls and the long valley of Siloam, when I have wandered round the glorious city, and looked far down the ravine. Surely nowhere else is such an impression of distance given by so short a space! When our camps were tense with knowledge of the war awakening, and of Allenby’s forward move at hand, I have watched the Australians on their tired horses filing up the last stages of the terrible trek from Jericho, man after man in that ghostly quiet, past Gethsemane, past the shadows of hill and olives. I have looked with an awful pity flooding the mind, with thought of their ordeal at hand, and the gallant hearts that a sword would pierce. From Olivet I have seen the city, a veritable New Jerusalem, with a power and appeal unknown by day. No words can describe a “sight so touching in its majesty.” Neither can words convey—no, not even dimly or afar off—the effect of the full, burning moon rising from the desert, over the hills of Moab. And there were hours of darkness, in the olive groves of Kedron, the fireflies glancing, the glow-worms lighting the stones. And memory casting its effulgent cloud about the spirit. “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning!”

Bush and Bird

As down the Kedron Valley I was riding,

Where olives veil the rock-cut tombs I saw

An owl, who neither for myself had awe

Nor of that glaring hour had thought save scorn,

But ruffed his wings and perked each feathered horn,

In anger that I came; but I was glad.

For why? You ask, as chiding

A mind so lightly stirred.

Know then, this joy I had

For sunlight on gray leaf and ragged stone;

But most to see, vouchsafed to me alone,

There, on Athene’s bush, Athene’s bird.

Sharon: Wreckage of Coast and Shore

It was a good thing that the completeness of Allenby’s victory gave us a clear run to Haifa, for from Caesarea northward a rocky rib projects, in antiquity a defence against the military peoples of the plain with their chariots and cavalry. Scarcely ever 50 feet high, it cuts off from observation of those travelling up Sharon the beach and a tiny strip of hinterland adjacent—a territory where you find Roman pillars rolled against the flint-man’s cave (still in use). The ridge is a thicket of lentisk, carob, genista, wild olive, which once covered the foreshore also. The Third Crusade from Haifa southward

“moved forward with more than wonted caution, impeded by the covert and tall and luxuriant herbage, which struck them about the face, especially the foot-soldiers. In these maritime parts were also numbers of wild beasts, which leapt from between their feet from the long grass and dense copse; many were caught, not by design but coming in their way by chance,”10

like the miscellaneous prey—jackals, a wild cat, partridges—with which the beaters at an Indian shoot emerge at the machans. A perfect trap of commingled rock and thorn, the ridge helped the Crusaders in their despairing limpet-clinging to the last strip of dominion, and made amends for the earlier suffering it caused them. It is fortunate that the Turkish machine-gunners never had their nests in it. A Crusader castle crowns the rough Carmel-facing slope at Kefr Lam, three corners intact. Petra Incisa, the road hewn through the rock rampart, is in front of Athlit, and above the precipice, commanding this narrow slit whose gates perished long ago, are traces of Détroits, the outer defences of Château Pèlerin (Athlit). In 1291, after even Acre had fallen, Athlit was the last fort to be wrested from the Christians. Its banqueting hall stands in part, with two human faces, one a bearded countenance in excellent clearness. Its moat is a red, rotting water, evil-looking, evil-smelling; a wide marsh abuts upon it, swampy fields where sandpipers race and herons fish. The defences on both sides run into the sea.

A tribe of earlier sea lords gripped this ridge, the handle to Palestine. Phoenician havens, tiny harbours of the Arsuf kind, dot the coast. “While the cruelty of many another wild coast is known by the wrecks of ships, the Syrian coast south of Carmel is strewn with the fiercer wreckage of harbours.”11 For example, at Tantura (Phoenician Dor) are rock-shelves for beaching galleys, and remains of a pier. Roman masonry, rubble piles, broken pottery, winejars, Samian ware, porphyry, lie everywhere. The cliff-top has remains of a Crusader tower, with winding staircase.

Over Caesarea, shadow of a great name, sands have drifted, forming dunes where only rushes and lentisk will grow, with, on the firmer ground, thymelsea, a few carobs and fewer oaks. From here to Zummorin the country is the loveliest for wooded verdure left in Palestine. Sharon means “Forest”; it was “the Forest” for Strabo and Josephus, was Tasso’s “Enchanted Forest” and Napoleon’s “Forest of Miski.” When war broke out groves straggled south from the still extensive woods north of Caesarea, the ragged fringes of a tattered robe. But there was wreckage here also; the Turk left behind his battle-line a trail of stumps. They are planting trees in Palestine again, especially in Galilee. But to those who have seen the native woodland plantations of fir and eucalyptus, even Balfour Forest, can bring small comfort.

At all hours of the day and most of the night cars fly over the sickle-curve of hard sands between Haifa and Acre. Two famous rivers cross it—Kishon, a noble stream flowing through a region of sand mounds and tamarisks, Kishon destined to provide boating, fishing and shooting; and Belus, which has its niche in history because the Phoenicians are said to have learnt how to make glass by the accident of lighting a fire on its sands. Both end amid palm groves, an unusual Palestine sight. Acre fort, which saw almost the last fighting of the Crusades, and has been through so many struggles, has become the home of countless lesser kestrels, which fly unrestingly round its walls.

Carmel

Sharon can be fair enough, but Carmel is the real beginning of that luxuriance which makes so striking a distinction between Judaea and Galilee. We jested about the place of our campaigning being “a land of milk and honey.” Yet, when the tide of success carried men out of the miserable desert-plains, they began to see with wonder how many features of beauty remained; and few can have reached Galilee or Lebanon without finding they had learned to love a country so richly and variously attractive. “Gad, but this is pretty country, this is,” said a brigadier as we came in sight of the approaches to Haifa. “I’d like to go over it with a gun.”

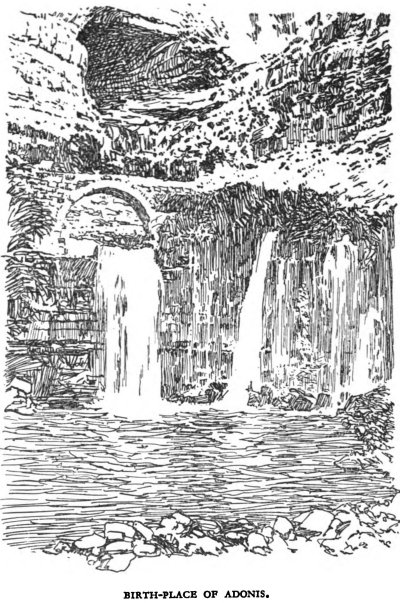

Sir George Adam Smith writes of riding over the ridges of Gilead, “where the oak branches rustled and their shadows swung to and fro over the cool paths.” He did what no living man will do again. Coppice remains in Gilead, but hardly a tree; the woods went to feed the Maan Railway. The hills which run up into the country’s heart, through Samaria and by Nablus, when the War finished had the appearance of a shaven sheep’s back, so cleanly had the trees been cut away almost to the crest. Lebanon was stripped, and Anti-Lebanon, and it was only in some of the western valleys that thickets of ilex and myrtle reminded that it was here that the young world’s imagination wandered, that Adonis died and Kypris ran wailing. Syrian coppice is perhaps the loveliest on earth. But the Syrian makes a sheer sweep of it, that he may then terrace up the hillside for vineyards.

But Tabor remained, and Carmel. Turkish axes had been busy on both, yet both remained, lovelier than description can convey. I went into the heart of Carmel early in April, 1919. I had seen it a month earlier, in its burst of wild lilies, when the Austrian Hospice had bowls filled with great velvet, all-but-black irises, and the slopes were lit with yellow asphodeline. It was glorious in Esdraelon then, at Carmel’s foot, with anemones, white, blue, and scarlet, and with the small gold iris. But in April the spring had ripened. For a dozen miles I went on till I reached the traditional scene of Elijah’s contest with the priests of Baal, when he strove with a people “halting on the threshold.” Carmel’s long summit, a plateau with rugged edges, glens dipping down to sea or Kisnon and wooded still, was one face of flowers.

The Mediterranean front had been ruined before the War by the German colony of Haifa; for the native woodland they had planted eucalyptus and pines. Among these pines were our G.H.Q. huts. We were making a second Kantara here, cutting down the pines, to make way for long wooden sheds. When the work of devastation had gone moderately far, plans were changed, and it was decided to make Carmel the summer home, not of G.H.Q., but of Corps. It mattered little. The Muses were unrepresented on either, and the wood-gods got short shrift from both. Corps or G.H.Q.—they recognised that it was “ pretty country,” good to go over with a gun.

So I struck inland. The copse had been slashed and broken up, but the flowery carpet remained. There were miles of cistus, both white and pink, a shrubbery in themselves, rough, dwarf bushes, covered with multitudes of daintiest blossoms. From the clefts hollyhocks sprang, and cyclamen, not yet finished flowering. Where cornfields had usurped the forest’s place, yellow marigold and gladiolus grew. Both of these are “of the cornfields” (chrysanthemum segetum and gladiolus segetum). Under the rock-roses crept their tiny kinsflower, the sun-rose (helianthemum); blue cornflowers were everywhere. Lilies were over, except for gladiolus, garlics, and omithogalum; but red ranunculus was out, following on the heels of red anemone, which had reigned during March. Marguerites, and those most ubiquitous of Palestine wild flowers, pink flax and cream-coloured scabious, were in their prime. Other flowers that I noticed were bur-marigold, pink campion, campanulas of several sorts, including one tall enough and with bells enough to be a wand for Silenus, the silvan deities’ jester; buplevrum, negella, knapweeds, thyme—carpets of thyme—thistles, pink bindweed, poppy, adonis (“tears of Christ”), yellow saxifrage, white clover, dwarf yellow trefoil. But the copse was Carmel’s greatest glory. A stray pine had seeded itself here and there, from those abominable Teuton groves. Yet, where the axe of war had spared it, the woodland kept its fresh, native sweetness. Styrax, a very showy plant, was in flower, hung with white tassels; arbutus, wild bay (laurus nobilis), and holm-oak (quercus pseudo-coccifera) were all blossoming. These, with hawthorn, no longer in flower, butcher’s broom, terebinth, and carob, made up the thicket—a thicket, as I have said, lovelier to my mind than great forests of magnificent trees. Cistus filled up the interstices and made a purfled fringe; red-berried burnet and coarse, pungent lentisk added a rough jungle of their own. Two sorts of broom were flowering, genista sphacelata and calycotome villosa. Blue salvia is almost a shrub, and was abundant; thymelaea (which looks somewhat like young box) is certainly one, but this was rare. By El-Moukraqa, the place of Elijah’s sacrifice, the wildest part of all this lovely region, I found a cephalanthera in the arbutus thicket—tall, waxen spikes of virginal whiteness.

From Carmel the pilgrim looks down to Homer’s wine-dark sea, and on the story of uncounted centuries. The old high place remains, muffled in with ilex and knee-holly. Vespasian, marching to stamp out Jewry, halted to consult the oracle of this god Carmel. To north that ancient river, the river Kishon, runs past the mound where tradition says the priests of Baal died. Beyond Kishon is Acre; north-east of Acre, Hermon stands, heaven-exalted, looking towards the Patmos sunsets. Southward you see Athlit, Castella peregrinorum, sea-engirdled on its promontory. You look on Sharon, and here, to the southeast, is Esdraelon, where Sisera fled and good Josiah died. Above Esdraelon is the sickle-sweep of Gilboa, where Saul and Jonathan perished. Against Gilboa is Tabor. Nazareth is in the hills. Never was such a background for man’s prosperity as this mountain doomed to become a fashionable residential quarter, a second Malabar Hill to the Bombay which will be built at Haifa.

Esdraelon and the Pagan Marches

The railway to Damascus skirts the edge of Carmel. To north are wooded hills, in front Esdraelon opens. You cross the Kishon, whose flowery swamps keep you company for some miles. These swamps attain their richest beauty in March, when the anemones rule. Red is arriving, purple is going, white is in its fulness. There are orchises and acres of golden asphodeline and a small gold iris, poppies and massed charlock colour the drier tussocks. Tamarisks stand like giant heaths, hung with pink racemes. But yellow is the prevailing tint. An occasional mimosa, dwarfed by the dampness, scents the air with its pale yellow buttons, spurge and saxifrage pour in their contribution to the general flush of golden bloom. All these flowers, in varying abundance, accompany you to the edge of Jordan Valley.

Far aloft, in pinnacled isolation, towers the Place of Sacrifice. Then you have finished with Carmel, and are in the plain of so many battles. In winter the levels are marshy, and through them trickle the water-streaks which swell the Kishon. In his last sandy miles Kishon has woven about him a many-moated defence of swamps, a refuge to wild swine and gazelles. When Gilboa and Tabor have thrown in their tribute of winter rains, he floods far, into pools long unvisited by any river-god, and Esdraelon is a quag. But through the summer it is dry prairie, formerly given over to thistles and broom-rapes and wild carrot. Plenty of water still lurks in hollows, tufted over with willow-herb or the darker green of rushes. But the terrain looks itself, a vast battle-ground, where through four millenniums of recorded history peoples clashed—Israel with Canaan and Midian and Philistia; Egyptian, Roman, Crusader, Saracen, Frenchman, Briton, Australian, Indian, Turk.

Round the red-roofed houses, Zionist settlements, grow mimosas and castor-oil shrubs in abundance, and a few gum trees. Tabor and Gilboa face each other, a contrast, the former dark with woods, the latter bare from its former luxuriance, as though the curse had been fulfilled, “Ye mountains of Gilboa, let there be no dew, neither rain upon you!” In a cleft to the south is Jenin, where the great surrenders were made in Allenby’s break through. Here, close to the railway, to north of you, is Little Hermon, which hides both Nain and Endor, scenes of two such diverse callings back of the dead.

From Beisan (Bethsan, where the bodies of Saul and Jonathan were exposed, after their death on Gilboa) you look down on the Jordan Valley. You enter territory whose associations are Greek and Roman, rather than Hebrew. Beisan was Scythopolis, a city hostile to the Jews, the most prosperous town of the Decapolis and, as its excavators are now reminding us, a centre of pagan culture.

The railway turns north, and seems to run on an edge, athwart a slope. Overhead are deserted bluffs, which look as if they should be robber-holds. Below is the amazing valley, ever new cause for wonder, though a man should see it a thousand times. The Jordan’s passage is marked by rank green, the beginnings of the Zor. The seasons are already changing, as you dip towards it—from a temperate climate you are moving slowly to a tropical one. The first sign of this, or ever the descent has well begun, is that white anemone, though in its prime on the plain, has almost finished and red is abundant (this is in March). Poppies, marigolds, blue iris, polygonums, flowers which can flourish in any heat, are the characteristic flowers. A fitful and despairing wind, wandering apparently without purpose, ruffles the parched grass in handfuls, as if it were some recumbent faun’s hair. It blows as it lists,

“Curling with unconfirmed intent

Along the mountain-side.”

Still you descend, till the valley is almost at your feet, and those iron heights beyond seem at hand. And now, till you reach the Lake of Galilee, the track is bordered with faded stalks of that lily of desolation, urginea maritima. The line turns half-right, you cross a thin trickle, an arm of Jordan, and presently are over the main river. It has just fallen in heavy cascades, and foams beneath, through black volcanic rocks, into a swirling race. Bushes of oleanders are swaying in the spray- cooled air. The train climbs slightly, running north again. The lake appears, the train swerves into a mimosa avenue, there are red-roofed houses. You have reached Es-Semakh, the scene of the bloodiest little fight in Allenby’s drive.

At the time, the story was of a white flag thrust from an upper window of one of these red-roofed houses, that first one. An Australian officer went upstairs to receive the surrender and was shot dead. A fight without quarter followed. The officer killed was well known, and his name was passed freely through the Force. But I am satisfied, as were most of the men who fought there, that there was no treachery. The 11th Australian Light Horse stumbled on the station and its workshops in the early darkness, when a white flag would not have been seen. What is certain is that the affair was a death-grapple between the Australians and the German artisans, which cost the 11th Light Horse dear.

Sernakh lies on a bare tableland, the beginning of the Jordan trench. A mile to the west, Jordan leaves the Lake, a stripling brook flowing between reeds and oleanders and agnus-castus. Lofty hills rise to east and west. The blue water glimmers in front, also shut with hills, Hermon’s huge mass lifting above all. Before they took in hand its damming, to provide power and lighting, the Lake was very shallow. One October evening, I had waded far out, when a black, suffocating khamsin swooped down on the shining mirror, darkening the tormented waves, blotting out the desolate plateau, maddening man and beast.

Eastward the Yarmuk valley offers a way into the Hauran, and to Damascus. The train leaves the dry plateau, its zizyphs and dead lilies and jaded grass. You enter the Muses’ canyon, a haunt of Baals and silvan deities, fauns and satyrs. Galilee is forgotten in this pagan world. Ever, as you climb towards the Hauran, you are entranced by the sight of shooting waters, of a foam-crowned brook dividing round verdurous islets, of giant ravines. Sprinkled at vast intervals are tiny settlements. I have been fascinated at night here by the glow of one fire, set deep in the solitary hillside, savage with scrub and thorn-tangles. Above was a black sky, with Hesperus lonely, winking over a mighty fell. The valley was in utter darkness, filled with the river’s continuous roar.

Yarmuk seems in perpetual spate. At the valley’s upper end, where the Hauran’s crest is cloven, are lofty waterfalls, and throughout its length the stream is never long without cascades. The slopes are clothed with white broom (Elijah’s “juniper,” retama raetam); far up are small clumps of ilex and carob. Marigolds are the characteristic flower, and sheet the valley from end to end—a golden forest. There is a tropical heat where the river enters the Jordan valley, and palms, plantains and castor-oil plants are cultivated. There is much black, oil-bearing shale.

I have said that this is pagan ground. On its northern hills the Christian armies were routed by the Moslems, A.D. 634, by which battle the Holy Land passed into paynim keeping. But this valley had never been really Christian or Jewish. Not three miles out of Es-Semakh is El-Hamme, the baths, a spa of Roman times and earlier. Gadara was on the hill behind El-Hamme, where its amphitheatre may be seen. The patron-name of the valley is a poet’s, Meleager, the flower-lover who gathered those incomparable blossoms, the Anthology. Amid these rocks he learnt what a light the evening sun casts on lilies, the “laughing lilies” of his verse. Here is iris, here are squills and hyacinths. A short journey will bring you to the Hautan, where “narcissus that loves the rain,” φίλομβρος νάρκισόος—surely never poet gave loveliness a more caressing name!—blows in its thousands.

At El-Hamme the air is sulphur-tainted, and a steam rises from the jungle, as from the primeval world. There is a circular basin, 5 feet deep—glassy-clear, with bubbles rising continually. There are the hot sulphur springs, the Baths of Callirrhoe. The heat is far too severe for a plunge; however cold the day, you lower your body with many gasps. In 1919 the place was never without Indians, some of whom seemed to spend the day sitting in the baths. Not 5 yards away, a chill, fresh spring rises, and the two waters join immediately in a smoking marsh, overgrown with dense, enormous reeds. All around is beautiful jungle. There are large-fruited zizyphs, of extraordinary height and luxuriance in this hothouse air, brambles, willow-herb, pink restharrow, loosestrife, aromatic mints of many sorts. A shallow brook drains the marsh, and almost at once harbours abundant fish. It makes its way rapidly to the larger river close by. Yarmuk is jubilant, a brimming, racing flood, fringed with a forest of brambles and oleanders—especially oleanders, a riot of red blossoms.

First Days in Damascus, 1918

In the first fortnight of October, 1918, when we were sharing a condominium with the chieftain our soldiers called “ Weasel, King of the Hedgehogs,” Damascus was a lively place. Rumour alleged that the residents in the Victoria Hotel each morning looked out on corpses lying in the streets, from the promiscuous slaughter of the night. The facts, though short of this, were sufficiently interesting.

On our way to Damascus my unit passed Deraa, that links the Hauran and Yarmuk, Og’s capital, with its underground, ancient city; it owned a more recent fame, because Turk and Arab had grappled here for the junction of the Hejaz and Palestine railways. From here Lawrence had flown in person to ask for help, and here two of crusader’s coast our ’planes had sent five enemy ones crashing to earth. The station had been bombed to a shell.

After Deraa we seemed to come upon the United Arab Nation on holiday. Over the black-lava-boulder-strewn Hauran mobs of Hejaz troops galloped frantically, sometimes as if they meant to charge the crawling train, more often nowhere in particular. Men in villages beside the track took pot-shots at the train, generally hitting it, for it was a long one and moved slowly. Its carriage-roofs were crowded with Feisal’s picturesquely-clad followers. Every one was happy, and every one seemed to have a rifle and more ammunition than he knew what to do with.

For hours, as we travelled, Hermon shut the western horizon, a vast, far-stretching mass, clouded but without snow. We had expected to see it snow-capped, and its brown bareness disappointed. We crossed Pharpar, beautiful with poplars and flowering blue brooklime, and were in the hollow where Damascus lies, a paradise of flowing streams and verdure. It was evening when we reached it. I climbed on to a station balcony to get my first view of the famous city. An Indian sentry below was showing his revolver to the excited crowd whom he was supposed to overawe. It went off in the hands of a white-bearded gentleman, luckily without hitting any one. The Indian in alarm reclaimed his toy, and scolded the crowd.