Enlist India for Freedom!

To

the Memory of

C. F. ANDREWS

and of our quarter-century of

unbroken friendship

“The real truth is that the public mind cannot be brought to attend to an Indian subject.”

— The Duke of Wellington, December 21, 1805.“The truth is, my dear Malcolm, that the great ones of this country are not interested in India.”

— The same to Sir John Malcolm, 1817.“Lord Ellenborough said he was aware of the little interest felt in that House upon any subject connected with the affairs of India, and he knew therefore that it would be irksome both to him and to them to address them at any length on such a subject.”

— Hansard, 23, p. 476: the date March 5, 1834. Lord Ellenborough was President of the Board of Control, precursor of our India Office; he was addressing the House of Lords.“Indian history has never been made interesting to English readers, except by rhetoric.”

— The Times, February 25, 1892.“The mere mention of the word India is enough to empty the smallest lecture-hall in the City.”

— Oxford saying, circa 1925.“India? India! But what’s wrong about India? There’s no reason to think about India!”

— A Member of the House of Commons to the author of this book, who was trying to point out that we ought to think about India sometimes—date, May, 1940.

Preface

On September 3, 1939, England declared war on Nazi Germany.

On October 21, the Indian National Congress, which formed the Government in eight of India’s eleven Provinces, withdrew its Ministries and India went back under the rule of British officials responsible only to the India Office in Whitehall, not to the Indian People. The deadlock continues to this day.

What is the National Congress? What were its Ministries? Why were they withdrawn? What is the Muslim League which we hear of as inflexibly opposed to Congress and representing a solid block of some seventy million Moslems? What is the present situation in India? Why did our own Government consider it wise, or at any rate unavoidable, to use India’s resources and man-power in a gigantic war without having asked India’s consent and while India can speak to us only through British or British-supported officials and a few yesmen? Was this course wise? Or unavoidable?

This book tries to answer these questions.

Contents

Part I — The Background of the Present Deadlock

- India Today

- How Is India Governed?

- The National Congress and the Moslem League

- Congress and British Foreign Policy

- India Is Declared a Belligerent. Congress Issues a Statement and Enquiry

- The Viceroy’s Answer

Part II — Problems of Self-Government in India

- The Moslems

- The Princes

- The Other Minorities

- The Punjab: Bengal: the Marathas

- Is India Fit for Self-Government?

- Can Britain and India Co-operate?

Part III — The Lines of a Solution

- The Cards which Congress Holds

- What Does India Want?

- Can We Retrieve a Lost Chance?

- What Should Be Done Now?

- Postscript. The Viceroy’s Latest Offer

Part One — The Background

Chapter I

India Today

If this war were being fought in 1890, the man in the street, the ordinary English-speaking citizen of the Empire, could perhaps continue to regard India as a complicated and distasteful but (thank God!) distant problem which was fortunately in the hands of trained officials competent to handle it. He could leave the incomprehensible East alone and get on with the war in the West.

But this is 1940.

We take the tightening-up of world communications for granted. We know that the old ‘time-lag’ which eased the speed of the travel of news from one country to another has utterly disappeared: that airways can carry men and mail in a few days to countries that only a few years ago were months apart. We know that, quite apart from improved literacy and means of getting information from the written word (cheaper books and more widely-distributed newspapers), the whole world now has the film and the radio and the opportunities they give for the distribution of information—and misinformation.

We accept the intense industrial modernisation of (Eastern) Japan and are inclined to regard her as a more formidable partner of Hitler’s Axis than (Western) Italy. We have heard with sympathy of the slower, more patient modernisation of China—its grasp of modern methods as applied to agriculture, its adoption of the more gracious aspects of our cities and universities.

But how much do we know of Modern India?

Is India still a distasteful problem to us? Do we still instinctively turn away from it? If we do, are not we, in this case, the Guilty Men? If there is no large body of informed opinion to encourage intelligent forward moves on our Government’s part, to check retrograde movements, are not we—the ordinary men and women of the Empire—to blame?

Either this war is a war for freedom—either the Empire is indivisible—its central islands, its Dominions, its colonies, rallying to a war of free peoples against a powerful—and hitherto successful—destroyer of freedom—or it is a thing of shreds and patches—bright shreds, dark patches.

Why should we not integrate the whole? Why should not the call that has integrated the rest of the Empire bring in India—an India divided between two honest loyalties—her passionate loyalty to the cause of world freedom that is now threatened by the dictators, and her steadfast loyalty to the ideal of her own freedom? Why can we not say to India, “Be one of us! And free”?

We are not at liberty to say this merely because the words sound like words we should like to say. We can only say this if we are prepared to implement the promise of freedom.

Can we do this? Is it wise or possible? What sort of freedom do we mean? When can it be given? Can we, who are ordinary people with little power, have any opinions worth having on this question?

We must have, unless Democracy is an open and discovered sham. Our Parliament is the ultimate source of power and appeal in all that affects India. We elect that Parliament. In that case, if Democracy is to be allowed to rule empires, we must be intelligent about India Today.

Many questions that have been in abeyance for centuries, or at any rate not ripe for the settling—questions of the first importance for the future of mankind—are being asked by the Time-Spirit now, and he will have an answer. One question is this: Can Democracy and ‘Empire’ co-exist? Another is: Must East and West always live apart?

I have been reading a book by a lady traveller recently returned from India. It is of a type that has flourished long and steadily, but should now, surely, die.

It is a bird’s-eye view—the view of a gay bird, flitting from one Government House to another and from one Prince’s guesthouse to another, skimming over the lovely Indian landscape, listening to what The Best People in India are saying about India Today. One sentence put the whole book into immediate focus. In it the writer prettily expressed surprise at the mechanical skill of her Indian chauffeur. She told us that even in the Ancient East one could find men who knew how to handle cars!

I was reminded of a lecture on China given by an American fellow-traveller on shipboard some ten years ago. The main point of the ‘lecture’ (given in a beautiful scarlet kimono) was that, though you would never think it, there were some very large shops in Shanghai. “Big stores, quite like those in America!”

Wake up, Westerners!

In India hundreds of thousands can manipulate machinery. In India is an immense reserve of men who would make good pilots, as already they make excellent car drivers. Indians are naturally better at flying than the Japanese, who have an anti-flying idiosyncrasy which in spite of their bravery makes them second-rate pilots. In India (though I am not one of those who rejoice in this) industries are being developed in all parts of the country. Millions travel, not only by train but by country motor buses. From India many thousands have travelled to Europe and America, have taken university degrees or special technical training courses, and have either returned to India to business or the professions or have remained to practise in the professions of foreign lands. In India are scientists, artists, writers known wherever there are people who care for civilisation, and many more who should be known better than they are. Many Indians have the latest European books and periodicals, not only in English but in French and German. These men and women are conversant with modern art, painting, ballet. They get at the present time a wide range and variety of radio news from many countries.

I happened to visit India last October, at a time of extreme tension. The Viceroy had replied to the manifesto of the Congress Working Committee and Congress had withdrawn its Ministries, sullen and humiliated.

I was invited to meet the Congress Working Committee, the day after the decision to withdraw the Ministries. We sat in Eastern fashion on low cushions, our shoes of course outside; only one of us, the Moslem who is now President of the Congress, sat on a chair. All this was ‘Oriental’, in the word’s conventional sense.

But their first question set me straight back in my own world. It ignored the stormy waters of controversy, and concerned—not world politics, not Indian politics, but—the kind of English used by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

His Grace was reported to have said that “on the whole Congress” during its term of office “had not been unduly unfair to the minorities”. These ‘Orientals’ alleged that this remark shed a floodlight on what they were pleased to consider the English ecclesiastical mind. “Does this mean that the English think unfairness right and ethical—so long as it does not become undue unfairness?”

What could an Englishman answer? I took refuge in the Common Law, by which no man can be held responsible for any nonsense except his own. They dismissed this as evasion.

So I pointed out, first, that the Head of the Church of England is a Scot and therefore could not be expected to understand the meaning of English words. (I have an inherited esteem for all Scots and deep interest in their ways—my ancestors lived in Cumberland, the county which for centuries had the job of keeping Scotland in order.) I explained further that no doubt His Grace was thinking in his own inherited fashion, along the lines of the Anglican attitude towards Nonconformists (being a Nonconformist, I knew all about this too), and his mind had been functioning back in the Tudor era. A sensitive speaker responds to his audience; and His Grace was addressing the House of Lords.

Finally, I referred the Working Committee to The Oxford History of India, which observes that after the storm of Bharatpur (January, 1826), “The glory of the achievement was dimmed by the excessive rapacity for prize-money displayed by Lord Combermere” (the Commander-in-Chief; I pointed out that he was a Welshman): i.e. Rapacity is right and normal in a Commander-in-Chief, but should not be ‘excessive’.

The Court grudgingly allowed ‘the English’ a clean bill, for this time only, and we got down to other business.

How many such gatherings could be collected in Britain—of men so conversant with the language of another country that they could take a native of that country to task for idiomatic misuse of it? Men who, confronted with a crisis in their land’s history, could meet it with such abundance of good humour and absence of resentment against another country which they well knew did not understand them, never had understood them, and would never take the trouble to understand them?

All over India there are such groups of civilised interesting men and women of the world. You get superb talk in India, but the best of it is when you are with the best Indians, for their minds traffic in two oceans, the thought of both East and West.

And in the villages? In the villages and the poorer quarters of the large cities of India there are millions of men and women who see modern films and news reels. And there are villages where men and women hear the radio—often a communal wireless set in the centre of the village, but still—a radio.

English villages are full of folk to whom the wireless is a godsend. Walk down any village street on a summer evening when the windows are open and the six o’clock news is on. You get the impression of brushing the surface of a great organism as complicated as the human body. There, behind those thin walls of brick, are the delicate capillaries of a blood-stream that pulses not only through a nation but through an Empire or, rather, through a world.

And, though as yet sluggishly, that blood-stream courses through India, too. India is a part of this modern world, of our Modern Empire. Bring her in more fully, as she longs to be brought in, to the full stream of the world’s life.

Chapter II

How Is India Governed?

British India is about 860,000 square miles in area, and Native India, which the Princes rule, 711,000. At the next Census (1941) it will probably be found that British India contains about 285 million people or even more, and Native India 90 million.

British India is divided into eleven Provinces, and a few oddments that are small special areas. Native India is divided up into very large, medium-sized, and small, sometimes very small, States. The British India and the Other India bits of all shapes and sizes fit in and out of the gigantic patchwork that forms the map of India.

British India, by the Government of India Act (1935), now has a Central Parliament with two Chambers, the Council of State and the Assembly. The Central Government has New Delhi for its winter seat and Simla for its summer one.

Each of the eleven Provinces was last October under a Governor and a Ministry whose Members were all Indians responsible to elected Legislatures (six have two chambers). These Provinces enjoyed self-government as regards those subjects relegated to the Provinces. The Punjab, Bengal, and Sind still function in this manner. But the North-West Frontier Province, the United Provinces, the Central Provinces, Bihar, Assam, Orissa, Madras, Bombay are now all of them back under autocratic rule and are run by the Governors and officials of the Indian Civil Service. These are the eight Provinces where Congress withdrew its Ministries.

The Evolution of Indian Self-Government

We may distinguish seven stages in the last hundred years:

1. A century ago, All India was under a Governor-General whose seat was Calcutta. Until 1834 he had a Council of three Members to assist him. In that year the celebrated Thomas Babington Macaulay was sent out as the first Law Member. Macaulay was sent to help in legislation only, and had no right to be present when executive business was discussed.

In 1834, there were also two Provinces, or, as they were called, Presidencies: Madras and Bombay. They were under Governors and Councils. They had enjoyed powers of legislation, which in 1833 were taken away from them (but restored later, though not in the former fulness). The Governor-General’s Council in 1834 legislated for All India.

In 1835, a third Province was added, under a Lieutenant-Governor: Agra or the North-Western Provinces,1 which today is part of the United Provinces.

In 1833, every position under the East India Company was declared open to all, whatever their race or creed. The same declaration was repeated in Queen Victoria’s Proclamation in 1858, which moved Miss Mayo to exclaim in her Mother India: “a bomb, indeed, to drop into caste-ridden, feud-filled, tyrant-crushed India!”

It would have been indeed a bomb if anyone had taken it seriously. Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India, twenty years later in a confidential letter to the Secretary of State for India, Lord Cranbrook, wrote:

“We all know that these claims and expectations never can or will be fulfilled. We had the choice between prohibiting them2 and cheating them, and we have chosen the least straightforward course. . . . I do not hesitate to say that both the Government of England and of India appear to me up to the present moment unable to answer satisfactorily the charge of having taken every means in their power of breaking to the heart the words of promise they have uttered to the ear”.

2. In 1853, the Law Member became a full Member of Council. The Governor-General, who had had a casting vote, was given a definite veto on his Council’s decisions. Right up to the present day one principle has been kept in Indian affairs—that an absolute power should rest somewhere—at first in the Home Government, then in the Governor-General as that Government’s representative in India.

Legislative Councils were set up accidentally, without any intention of doing this. In 1853, a definite Legislative Council at the Central Government began to grow up; six ‘Added Members’ were appointed to the Governor-General’s Council, two being judges and four representing the four Provinces then existing (Bombay, Madras, the North-Western Provinces, and Bengal, which was now created a separate Province).

3. 1861 was a time of general overhauling; the Mutiny had recently ended.

The judges were dropped from the Governor-General’s Council, and he was allowed to appoint up to another twelve added Members. Two Indians were nominated for the first time.

The former Added Members had got into bad ways. They had sometimes tried to ask questions about administration and executive policy, and even to criticise. This was now forbidden. They must devote their attention to legislation.

Legislative arrangements continued chaotic. The Provinces had limited powers of legislation, but for some subjects must get previous consent from the Governor-General (who now becomes called also the Viceroy), who could veto their legislation as well as with his own Council legislate for the Provinces.

Only Madras, Bombay, and Bengal were allowed Legislative Councils.

The Provinces were gradually growing in number. Assam was put under a Chief Commissioner, 1874. The North-Western Provinces were united with Oudh, 1877, and received their modern name of the United Provinces. Other shufflings and reshufflings took place in 1905 and 1911.

The United Provinces received a Legislative Council in 1886, Burma and the Punjab received theirs in 1897. At various times small Executive Councils came into being, the Punjab receiving one in 1920, up to which time its Lieutenant-Governor was in sole charge of administration. There were so many changes that I cannot note them all. The point is, some Provinces, notably the Presidencies of Bombay and Madras, have a much longer tradition of some degree of independence, whereas the Punjab has slowly and unwillingly come over to the idea of representative government. These facts are not without importance.

4. In 1892 came Lord Cross’s Indian Councils Act. This added a few more Members, and the Viceroy’s Council might now contain as many as sixteen Additional Members. The Provinces too had their own tiny Councils, and here there was a jump to twenty Additional Members, of whom eleven were to be non-officials. “The elective principle now cautiously raised its head”.3 Municipalities, University Senates, commercial organisations, were allowed to nominate members. Members were allowed the right of ‘interpellation’; that is, they might ask the Executive Councillors questions about acts of the Administration. But their work was not administration, it was legislation.

5. The Morley-Minto Reforms, 1909. The Central Legislative Assembly was enlarged from twenty-one to sixty. The Provincial Councils were doubled.

The ‘communal’ principle was introduced. Certain minorities, notably the Moslems, were reserved a certain definite representation.

These Reforms were hailed by Indians with delight. They are a very patient race. In their own legends it is quite usual for a god or even a human hero to wait for a thousand years.

6. In 1921, the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms came into operation.

The Provincial Legislative Councils were again enlarged, and in some of them officials were now in a minority. The Imperial Government was given a second chamber, the Council of State (sixty Members, of which thirty-three were elected).

The franchise embraced about three per cent of the total Indian population. The most important feature of these Reforms was ‘dyarchy’, division of rule. Certain subjects were transferred to the Provincial Legislative Councils and were put under Indian Ministers responsible to these Councils.

There are many objections to dyarchy, and it is rarely given a good word. It was defended as an attempt to train Indians by degrees for full self-government later, and although as a result of India’s help in the War much more had been expected the Reforms would not have worked so badly if it had not been for the Jalianwalabagh massacre, of April, 1919, when General Dyer shot down close on 2,000 people (379 dead and about 1,200 wounded were the official figures) in a few minutes. I am not going to enter on this controversy here, beyond remarking that for Indian opinion this incident and the way it was received by influential bodies of British opinion have divided British-Indian history into two epochs as distinctly as the Mutiny has divided it for us. General Dyer’s action was condemned by both the Indian and Home Governments, and by the highest military authority. Unfortunately, his admirers in India and Britain presented him with a sword of honour and £26,000, and the House of Lords exonerated him; and in both Houses of Parliament were debates in which many members clearly expressed their view that Indian lives counted for far less than British lives.

All this made the worst possible beginning for the new Constitution.

Dyarchy was for the Provinces only. It did not affect the Central Government, which since 1911 had been in Delhi. This Government could still overrule all other Governments, even in the transferred subjects.

Dyarchy did better than is generally admitted. But the National Congress, the most powerful political party in the country, refused to co-operate, and was joined by the majority of the Moslems, who had their own additional cause for anger, in the post-war treatment of Turkey, a Moslem country.

7. The Government of India Act, 1935.

This was the result of the Round Table Conferences. There was to be a Federation, into which the Princes agreed to enter, nominating their representatives to the Central Legislature. This Legislature was to have, as before, two Chambers: the Council of State with 260 seats (104 for the Princes) and the Assembly with 375 seats (125 for the Princes). There were to be eleven Provinces (Burma being separated from India), with Cabinets of Indian Ministers.

The Viceroy still kept his own Executive Council, now consisting of himself, the Commander-in-Chief, three other British Members, and two Indian Members. (This Council is often called a Cabinet, but this is incorrect.) Four departments—Defence, Foreign Affairs, Ecclesiastical Affairs, and Excluded Areas (small pockets of separately administrated territory scattered over India)—were under the Viceroy alone. Relations with the Princes remained with the Viceroy.

The whole scheme is riddled from top to bottom with ‘safeguards’, some of them in the Viceroy’s hands, some in those of the Secretary of State in London (who kept the sole power of appointment to the Police and Civil Service), and the Central Legislative Chambers are so composed that whatever else may be heard there it will not be the voice of the people. It is so difficult to keep patience while considering it—if you have any sense of fairness—that I will dismiss a distasteful subject with the words of Professor Berriedale Keith:4

“For the federal scheme it is difficult to feel any satisfaction. The units of which it is composed are too disparate to be joined suitably together, and it is too obvious that on the British side the scheme is favoured in order to provide an element of pure conservatism in order to combat any dangerous elements of democracy contributed by British India. On the side of the rulers5 it is patent that their essential preoccupation is with the effort to secure immunity from pressure in regard to the improvement of the internal administration of their states. Particularly unsatisfactory is the effort made to obtain a definition of paramountcy which would acknowledge the right of the ruler to misgovern his state, assured of British support to put down any resistance to his régime. It is difficult to deny the justice of the contention in India that federation was largely evoked by the desire to evade the issue of extending responsible government to the central government of British India. Moreover, the withholding of defence and external affairs from federal control, inevitable as the course is, renders the alleged concession of responsibility all but meaningless.”

The Princes have not yet come in, so Federation has been postponed.

What did India gain from the Round Table Conferences and the Government of India Act?

This, chiefly: that the principle of majority rule (subject to ‘weightage’ or representation in excess of a minority’s numerical proportion) was accepted. That principle is now being challenged and is in danger of being lost.

They gained also self-government—inside a limited sphere and with great stringency of funds—in the Provinces.

In the last stages (1933) of the Joint Select Committee (as the final sessions of the Round Table Conference were styled) a Joint Memorandum of over a hundred points was put up, covering concessions and changes which would make the Committee’s coming decisions acceptable to Indian opinion. This Memorandum was signed by all the Indian groups, not merely the Liberals or Moderates, but by the Moslems’ and Untouchables’ representatives and by Sir Hubert Carr, who was the leader of the European business men, and by Sir Henry Gidney, who represented the Anglo-Indian or ‘domiciled’—largely Eurasian—community. The memorandum was brushed aside entirely.

The Round Table Conference left bitterness and small sense of obligation for the new Constitution. Congress contested the elections in 1937, and won them, with absolute majorities in six Provinces (which became seven when a non-Congress group joined Congress in another) and as the largest single party in two more Provinces. For some months they refused to form Ministries, and ‘caretaker’ Ministries conducted a phantom unhappy existence. After negotiation concerning the Governors’ use of their powers of veto, eight Congress Ministries were formed.

These were the Ministries that resigned last October.

Chapter III

The National Congress and the Moslem League

The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885, largely by the efforts of some sympathetic British officials (with considerable encouragement from the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin) who thought that there should be some sounding-board for enlightened Indian opinion, some means by which that opinion could express itself.

The Moslem (or Muslim) League was founded in 1906, twenty years later, when the first considerable step forward towards self-government (that afterwards known as The Morley-Minto Reforms) was being discussed behind the scenes. This discussion was no secret; in India everything is known (including a good deal that does not exist)—it was an Eastern book, which once had considerable vogue, that reminds us that whatever you say in private will be talked over that same evening by the women on their flat housetops.

Congress membership is obtained by an annual payment of four annas (sixpence). The Moslem League now has a membership based on a two annas payment. The Congress membership is about four-and-a-half millions; the Moslem League strength does not seem to be published. Both these bodies have had large recent accessions, a reflection of the universal desire to “get on to the band-wagon”. Many whose political interest had not been very noticeable hastened to join the Congress when it won its overwhelming victories three years ago. Membership was clearly the way to ministerial office.

This zest to get on the band-wagon has had its funny side. In the old days, applicants for jobs used to send chits that proved their utter ‘loyalty’, even sycophancy. When Congress became H.M. Government, chits came in showing that the petitioner had been for years thoroughly unsound from the former Government point of view—had been in prison or ought to have been in prison. Often the man who had sent in the former kind of certificate forgot this and sent in the kind he supposed was now in favour; and the Congress Minister concerned found a grim pleasure in comparing both sorts side by side in the same dossier.

Mr. Gandhi’s recent efforts have been largely devoted to shaking off these new enthusiasts and trying to get down to basic strength, in case he has to launch Civil Disobedience again (that strategist Gideon, it will be remembered, similarly shed all but a handful of completely trustworthy followers, on the eve of his battle with the hosts of Midian).

The Moslem League has gained in the same fashion as Congress, since it became the Government practice to treat its President, Mr. Jinnah, as a kind of Moslem Mahatma. It is convenient to fine essential discussion down to two or three ‘key’ men. There are, nevertheless, strong Moslem groups (as we shall see) who reject Mr. Jinnah’s leadership, just as Congress (often assumed to be synonymous with Hinduism) in recent days is opposed by the Hindu Mahasabha with even more bitterness than the Moslem League. The Congress leaders are considered to be bad Hindus, as some of them certainly are.

Leadership filters down through groups of varying size, but is concentrated at the top in what is styled a ‘Working Committee’, often referred to as ‘the Higher Command’ (of Congress or Moslem League). Other groups besides Congress and the Moslem League have these Working Committees. The Congress Working Committee consists of a dozen to perhaps a dozen and a half members; the Moslem League’s Working Committee is rather smaller. The Working Committee is chosen by the President, as the British Cabinet by the Prime Minister.

The annual meetings of Congress have been held in important cities all over India, to familiarise Indians with its work. These meetings used to be held in Christmas week or the week following, but latterly have been held earlier or later in the cold weather.

Emergency meetings of Moslem or Congress Working Committees are often held in Delhi, since this is only a few miles away from New Delhi, the seat of the Central Government, which is very likely in negotiation with these bodies. But many Congress Working Committee meetings have been at Wardha, which is almost exactly in the centre of India and close to Mr. Gandhi’s home at Segaon.

Mr. Gandhi is not a Member of the Congress Working Committee, he is not even a four-anna member of Congress. He is one of the world’s very few hundred-per-cent pacifists (only one member of the Working Committee is this) and he resigned because he did not feel that the Congress atmosphere was really hundred-per-cent ‘non-violent’. But it does not in the least matter what Mr. Gandhi calls himself. He has co-opted himself a life member of all Congress gatherings, and when his inner voice tells him he should be present he is present.

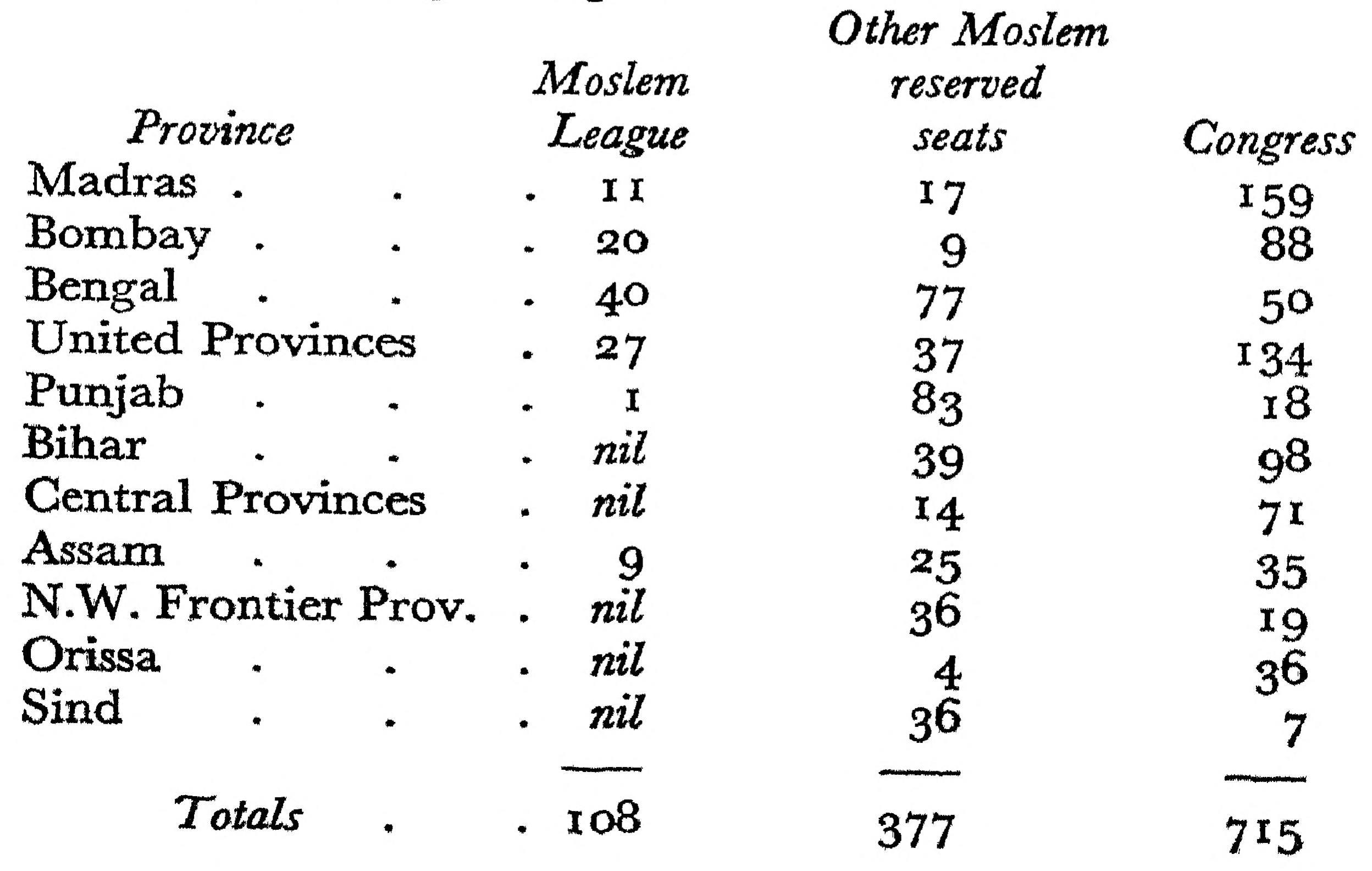

At the provincial elections (1937) these parties emerged with the following strength:

Other categories bring the total of all seats in these Legislatures up to 1585. It must be remembered that only 657 were ‘general seats’, open without reservation to all parties. India’s electoral arrangements make her Parliaments rather resemble a series of Mappin Terraces, where each species has its assigned habitat.

Both Congress and Moslem League gained some strength by post-election accessions, when the work of Cabinet-making was in progress. These made them the largest single parties in Bengal and the N.W.F.P. respectively, where a Coalition Government under a Moslem League (ex-Congress) Premier and a Moslem Congress Government were formed.

Mr. Jinnah’s first and most stressed demand before there can be a settlement is that the Moslem League shall be recognised, not by Government only but also by Congress, as speaking for all Moslems. This demand Congress refuses, on two grounds: (1) that it would throw over not only the Moslems who are in the Congress but other groups which are often in friendly alignment with it; (2) that it would accept the label which it has steadily refused, of being a Hindu body. The Mahasabha, not Congress, is the Hindu sectional organisation.

Chapter IV

Congress and British Foreign Policy

When the first seven Congress Ministries were formed, if Congress had been willing to form Coalition Governments (one was formed later in Assam) two Provinces, Sind and Bengal, which are now non-Congress, would also have been Congress Provinces. The present Moslem Premier of Bengal was then a Congressman and was willing to serve in a Congress Ministry. In Sind the Moslem League had been routed and was in opposition, and the Ministry was a Moslem Ministry on friendly terms with the Congress Members of the Legislature; at the annual celebration last January of what is styled Independence Day, the Moslem Premier of Sind led the Congress procession.

We have known, since the Khaki Election of the Boer War, some sweeping electoral victories in Britain. But no British political party has ever approached the success of the Congress in the Indian elections, despite the system by which numerous minority groups, racial or religious, have seats reserved for them alone.

Even when we formed our first National Government in Britain, in 1931, there were groups who were not sure that it quite represented their feelings and opinions. But we always insist on 100 per cent unanimity in India. If you sweep the horizon with field glasses you can always find some dissidents somewhere—the last Secretary of State, for example, when he printed last autumn the Congress manifesto as a white paper managed to find a statement by Indians who disagreed with it—and a very interesting catch he made! It is queer that we—who have perhaps more individuals and even eccentrics than any other nation—seem to think there ought not to be any in India!

The answer to the question, Why did Congress pull out its Ministries? is to be found in India’s profound dislike and distrust of our foreign policy over a period of years. On this point, at any rate, Congress spoke for India.

Do you think the Moslems liked what happened in Abyssinia or Albania? Or the stress laid in some British circles on the Catholic and Christian character of the aggressors in Abyssinia and Spain? Even now, our spokesmen talk far too much and unwisely about the present war being a Christian Crusade. It is something greater and nobler than the Crusades ever were.

Ever since Japan began the aggression business, at its annual meetings Congress has passed resolutions of increasing stringency deploring our foreign policy, pointing out its perils, and affirming India’s refusal to be involved in war without her consent.

The wording of these resolutions carried the sign-manual of the vigorous internationalism and sturdy ethical principles of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, whose Autobiography has made him hardly less famous in the outside world than Gandhi himself. His views were practically indistinguishable from those held and trenchantly expressed by our own Prime Minister, Mr. Winston Churchill, by many Conservatives in this country, and by most of the Liberal and Labour Parties.

These years of deepening disaster, to many of us of all political parties, have seemed to be no mystery as they were passing; it has been like reading off a blackboard or (to change the metaphor, to one used to me by Alexander Korda, six months before Munich) like waiting on a station for a collision and crash which you knew was certainly coming. If at any time during the past six years Mr. Winston Churchill, Mr. Franklin Roosevelt, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had found themselves in the same room discussing foreign affairs and Britain’s foreign policy, they would have found themselves in complete agreement. The Indian had this added misery, of knowing that his own country was throughout a tool and puppet—that she could do nothing except utter protests which no one heard, and that when the crash came she would be dragged along the line with it.

Here are a few quotations:

“This Congress sends its warmest greetings to the people of China and its assurances of full sympathy with them in their fight for emancipation and records its condemnation of the action of the Indian Government in refusing passports to the Medical Mission which the All India Congress Committee wanted to send to China. . . . The Congress declares that the people of India . . . desire to live at peace . . . and asserts their right to determine whether or not they will take part in any war”. (December, 1927).

“Since the last session of the Congress the crisis has deepened and Fascist aggression has increased, the Fascist Powers forming alliances and grouping themselves together for war with the intention of dominating Europe and the world and crushing political and social freedom. The Congress is fully conscious of the necessity of facing this world menace in co-operation with the progressive nations and peoples of the world, and especially with those peoples who are dominated over and exploited by Imperialism and Fascism. In the event of such a world war taking place there is grave danger of Indian man-power and resources being utilised for the purposes of British Imperialism, and it is therefore necessary for the Congress to warn the country again against this and prepare it to resist such exploitation of India and her people. No credits must be voted for such a war and voluntary subscriptions and war loans must not be supported and all other war preparations resisted”. (December, 1936).

“Fascist aggression has increased and unabashed defiance of international obligations has become the avowed policy of Fascist Powers. British foreign policy, in spite of its evasions and indecisions, has consistently supported the Fascist Powers in Germany, Spain and the Far East, and must therefore largely shoulder the responsibility for the progressive deterioration of the world situation. That policy still seeks an arrangement with Nazi Germany and has developed closer relations with Rebel Spain. It is helping in the drift to imperialist war.

“India can be no party to such an imperialist war and will not permit her man-power and resources to be exploited in the interests of British Imperialism. Nor can India join any war without the express consent of her people”. (February, 1938).

Munich: And After

India’s destiny and her relations with Britain seem to have been handed over by Providence to Harrovians: Lord Baldwin, Lord Zetland, Sir Samuel Hoare, Mr. Winston Churchill, Mr. L. S. Amery, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. They fall neatly into two groups, of appeasers and anti-Fascists.

Nehru keeps, with half-rueful amusement, his photograph in O.T.C. uniform, and he likes Byron’s poetry much better than he should, because (he admits the reason) Byron was at Harrow, where after the first bleakness which we all experience at a public school Nehru was happy and liked. In the National Congress they twit him with his ‘Anglo-Saxon’ ways. When I entered the room where the Working Committee were, last October, Rajagopalachari, the Madras Premier, responded to my greeting with an outstretched hand, and then apologised. “It is his Anglo-Saxonism” (with a wave towards Jawaharlal) “that gets us into these bad ways.” It is usual to say that Nehru thinks “like an Englishman.” “Talk that over with Jawaharlal,” said Gandhi to me, some years ago. “He thinks like your people.” This does not prevent his being as strong a patriot as you can find anywhere. Too much stress is laid on his “Englishness”.

At any rate, during the pre-Munich crisis he wrote all like an Englishman. He was in Prague through much of that summer when Lord Runciman was helping the Czechs to settle their troubles and wrote me letters of which not one comma needs to be changed today. Since his judgments went back to India and spread far through his own people, I am going to show how he thought and felt:

“Czechoslovakia is not a place to cheer one up just at present. I have just returned from the Sudeten German areas. It was a profitable visit and I learnt much. The majority of the Henleinites are past reason and live in an emotional state of exaltation expecting the millennium, in the shape of Hitler, to come at any moment and unloose their hands to take vengeance on their opponents. I believe careful records and even pictures of many of their local opponents are kept for the purpose. A minority of Henlein’s party is in it through sheer terror. After the collapse of Austria it seemed that the fate of Czechoslovakia was sealed and it was natural for them to take refuge in Henlein’s party. Apart from this the principal reason for the growth of Henlein’s party has been the collapse of the glass industry, throwing large numbers into unemployment.

“The German Social Democrats in the Sudeten areas are depressed but are bearing up fairly well. They know well the fate in store for them if Hitler comes. The Czechs are behaving well, though occasionally perhaps a little chauvinistically. Long years of suppression and the past months of continued insult and aggression from across the frontiers have put their backs up, and they have come to the conclusion that they will have to fight for their existence. They keep in readiness for this and believe that they can give a good account of themselves, though they have no illusions about the power of their opponents and the terrible nature of this strength. Having come to this conclusion they are singularly calm and ready for all eventualities. . . .6

“But something that has astounded me enormously is the attitude of our too per cent pacifists. . . . I find it nauseating that——7 should go backwards and forwards . . . and do all the dirty work of Hitler—and all in the sacred name of peace. Why does he not transfer his energies to the Trentino where Germans are really being oppressed by Mussolini?

“What a tremendous responsibility the British Government has to shoulder today, for ultimately it is its policy that will lead to peace or war in Central Europe! And that policy is leading to war today!” (August 15, 1938).

This is how he felt when he left Europe:

“I am on my way to India, and as I go I see that Lindsay has been defeated. . . .8 One expected that end, yet I did not think the majority would be quite so big. Personally I think that the reaction from all this madness will come soon. But where is the leader for this? I do not see him anywhere in England”. (October 29, 1938).

We can guess how Nehru felt after Munich, and how India felt. At the next annual meeting, at Tripuri (March, 1939), as simultaneously Hitler seized Czechoslovakia and Mr. Chamberlain gave our pledge to Poland, Congress couched its annual warning in terms of desperation:

“The Congress records its entire disapproval of British Foreign Policy culminating in the Munich Pact, the Anglo-Italian Agreement and the recognition of Rebel Spain. This policy has been one of deliberate betrayal of democracy, repeated breach of pledges, the ending of the system of collective security, and cooperation with governments which are avowed enemies of democracy and freedom. As a result of this policy, the world is being reduced to a state of international anarchy where brute violence triumphs and flourishes unchecked, and in the name of peace stupendous preparations are being made for the most terrible wars. International morality has sunk so low in Central and South-western Europe that the world has witnessed with horror the organised terrorism of the Nazi Government against people of the Jewish race and the continuous bombing from the air by rebel forces of cities and civilian inhabitants and helpless refugees.

“The Congress dissociates itself entirely from British Foreign Policy which has consistently aided the Fascist Powers and helped in the destruction of democratic countries. The Congress is opposed to Imperialism and Fascism alike and is convinced that world peace and progress require the ending of both of these. In the opinion of the Congress, it is urgently necessary for India to direct her own foreign policy as an independent nation, thereby keeping aloof from both Imperialism and Fascism, and pursuing her path of peace and freedom.”

Chapter V

India Is Declared a Belligerent. Congress Issues a Statement and Enquiry

The rest followed automatically.

In the summer an Amending Act to the Government of India Act pulled back into the Viceroy’s hands in case of war the very considerable powers of self-government enjoyed by the eleven Provinces, “the very Constitution which brings the Provincial Assemblies into existence”, thereby underlining

“the very subordinate position which the liberties of the Indian people occupy in the counsels of Britain and the ease and facility with which those liberties can be touched and frustrated, while whenever there is a question of enlarging them all imaginable difficulties and obstacles are put forward”.9

The British Parliament meant no special insult; it was preoccupied with other affairs and hardly noticed what it had done.

In September, India was declared a belligerent, without the formality of consulting either her Central Assembly or the Provincial Assemblies. Eire, Britain’s closest neighbour, stayed neutral: South Africa hesitated: Iraq, Egypt, the Indian Princes, spoke for themselves.

“How very galling it is to us that we should not have any say even in those matters of vital importance which are of intimate concern to everyone amongst us. We are asked to fight, not because we choose to fight but because England wants us to fight. Small colonies which started life only yesterday and which have hardly two or three per cent of our population are free to make their own choice for peace or for war. It is open to Eire to remain neutral if it so chooses. It is open to the Union of South Africa to keep aloof if it so chooses. As you are doubtless aware, the Prime Minister of that state, General Hertzog, was defeated by only a small majority when he sponsored a resolution for neutrality in war. Canada and Australia have decided for themselves. They were consulted at every stage in the course of the present crisis. . . . None of the provincial governments was ever shown the courtesy of being consulted in this matter or in any matters pertaining to the war. Even that nominally representative body, the Central Assembly, was not consulted. Is our position no better than that of a vassal or of a serf or a galley slave, whose life is at the disposal of his master? He cannot say whether he will enter the lists or not. He must when he is asked to. . . . Mr. Chamberlain said that the new order would be based on mutual confidence and mutual trust. This is the trust that has been reposed in us.”10

Since foreign policy, which of course includes the right of declaring war, was a reserved subject, in the Viceroy’s hands, this action was technically correct and legal, by the Constitution Britain had bestowed on India. But whenever there arises a conflict of legal with moral right, the latter will sweep the board. In the American Revolution this country had a case against the rebels (as historians now admit), but because the revolutionaries focused the quarrel on their claim that “taxation without representation is tyranny” our own conscience and the judgment of the world and historians gave the case against us.

The National Congress focused their quarrel on the claim that no country has the right to commit another to a war without its consent. “India,” a distinguished soldier said to me, “has a strong moral case”. He added, however, with emphasis in his tones, “No one is going to ask India to suffer any casualties”.

You see, last autumn it was ‘a phoney war’; all we had to do was to enforce as much blockade as we could and make cheerful speeches and Germany would crack from within.

The Congress Working Committee had appointed a War Emergency Committee of three,11 who drew up a manifesto which was sent out, September 14, asking what were the British Government’s war aims and if the war were really one for freedom and democracy and how these aims would be applied to India. As this document is destined to take a permanent place in the literature of freedom, I make no apology for giving it nearly all. It deals with much more than the immediate issues.

“The Working Committee have given their earnest consideration to the grave crisis that has developed owing to the declaration of war in Europe. The principles which should guide the nation in the event of war have been repeatedly laid down by the Congress, and only a month ago this Committee reiterated them and expressed their displeasure at the flouting of Indian opinion by the British Government in India. As a first step to dissociate themselves from this policy of the British Government, the Committee called upon the Congress members of the Central Legislative Assembly to refrain from attending the next session. Since then the British Government have declared India as a belligerent country, promulgated Ordinances, passed the Government of India Act Amending Bill, and taken other far-reaching measures which affect the Indian people vitally, and circumscribe and limit the powers and activities of the provincial governments. This has been done without the consent of the Indian people whose declared wishes in such matters have been deliberately ignored by the British Government. The Working Committee must take the gravest view of these developments.

“The Congress has repeatedly declared its entire disapproval of the ideology and practice of Fascism and Nazism and their glorification of war and violence and the suppression of the human spirit. It . . . must therefore unhesitatingly condemn the latest aggression of the Nazi Government in Germany against Poland and sympathise with those who resist it.

“The Congress has further laid down that the issue of war and peace for India must be decided by the Indian people, and no outside authority can impose this decision upon them, nor can the Indian people permit their resources to be exploited for Imperialist ends. Any imposed decision, or attempt to use India’s resources for purposes not approved by them, will necessarily have to be opposed by them. If co-operation is desired in a worthy cause this cannot be obtained by compulsion and imposition, and the Committee cannot agree to the carrying out by the Indian people of orders issued by external authority. Co-operation must be between equals by mutual consent for a cause which both consider to be worthy. . . . But India cannot associate herself in a war said to be for democratic freedom when that very freedom is denied to her and such limited freedom as she possesses taken away from her. . . .

“Again it is asserted that democracy is in danger and must be defended and with this statement the Committee are in entire agreement. The Committee believe that the peoples of the West are moved by this ideal and objective and for these they are prepared to make sacrifices. But again and again the ideals and sentiments of the people and of those who have sacrificed themselves in the struggle have been ignored and faith has not been kept.

“If the War is to defend the ‘status quo’, imperialist possessions, colonies, vested interests and privilege, then India can have nothing to do with it. If, however, the issue is democracy and a world order based on democracy, then India is intensely interested in it. The Committee are convinced that the interests of Indian democracy do not conflict with the interests of British democracy or of world democracy. But there is an inherent and ineradicable conflict between democracy for India or elsewhere and Imperialism and Fascism. If Great Britain fights for the maintenance and extension of democracy, then she must necessarily end imperialism in her own possessions, establish full democracy in India, and the Indian people must have the right of self-determination by framing their own constitution through a Constituent Assembly without external interference, and must guide their own policy. A free democratic India will gladly associate herself with other free nations for mutual defence against aggression and for economic co-operation. She will work for the establishment of a real world order based on freedom and democracy, utilising the world’s knowledge and resources for the progress and advancement of humanity.

“The crisis that has overtaken Europe is not of Europe only but of humanity and will not pass like other crises or wars leaving the essential structure of the present day world intact. It is likely to refashion the world for good or ill, politically, socially and economically. This crisis is the inevitable consequence of the social and political conflicts and contradictions which have grown alarmingly since the last Great War, and it will not be finally resolved till these conflicts and contradictions are removed and a new equilibrium established. That equilibrium can only be based on the ending of the domination and exploitation of one country by another, and on a reorganisation of economic relations on a juster basis for the common good of all. India is the crux of the problem, for India has been the outstanding example of modern imperialism and no refashioning of the world can succeed which ignores this vital problem. With her vast resources she must play an important part in any scheme of world reorganisation. But she can only do so as a free nation whose energies have been released to work for this great end. Freedom today is indivisible and every attempt to retain imperialist domination in any part of the world will lead inevitably to fresh disaster.

“The Working Committee have noted that many Rulers of Indian States have offered their services and resources and expressed their desire to support the cause of democracy in Europe. If they must make their professions in favour of democracy abroad, the Committee would suggest that their first concern should be the introduction of democracy within their own States in which today undiluted autocracy reigns supreme. The British Government in India is more responsible for this autocracy than even the Rulers themselves, as has been made painfully evident during the past year. This policy is the very negation of democracy and of the new world order for which Great Britain claims to be fighting in Europe.

“As the Working Committee view past events in Europe, Africa and Asia, and more particularly past and present occurrences in India, they fail to find any attempt to advance the cause of democracy or self-determination or any evidence that the present war declarations of the British Government are being, or are going to be, acted upon. The true measure of democracy is the ending of Imperialism and Fascism alike and the aggression that has accompanied them in the past and the present. Only on that basis can a new order be built up. In the struggle for that new world order, the Committee are eager and desirous to help in every way. But the Committee cannot associate themselves or offer any co-operation in a war which is conducted on imperialist lines and which is meant to consolidate imperialism in India and elsewhere.

“In view, however, of the gravity of the occasion and the fact that the pace of events during the last few days has often been swifter than the working of men’s minds, the Committee desire to take no final decision at the stage, so as to allow for the full elucidation of the issues at stake, the real objectives aimed at, and the position of India in the present and in the future. But the decision cannot long be delayed as India is being committed from day to day to a policy to which she is not a party and of which she disapproves.

“The Working Committee therefore invite the British Government to declare in unequivocal terms what their war aims are in regard to democracy and imperialism and the new order that is envisaged, in particular how these aims are going to apply to India and to be given effect to in the present. Do they include the elimination of imperialism and the treatment of India as a free nation whose policy will be guided in accordance with the wishes of her people? A clear declaration about the future, pledging the Government to the ending of Imperialism and Fascism alike, will be welcomed by the people of all countries, but it is far more important to give immediate effect to it, to the largest possible extent, for only this will convince the people that the declaration is meant to be honoured. The real test of any declaration is its application in the present, for it is the present that will govern action today and give shape,to the future. . . .

“The Committee earnestly appeal to the Indian people to end all internal conflict and controversy and, in this grave hour of peril, to keep in readiness and hold together as a united nation, calm of purpose and determined to achieve the freedom of India within the larger freedom of the world”.

Next day (September 15, 1939) Mr. Gandhi issued his own separate comment, in course of which he said:

“The author of the statement is an artist. Though he cannot be surpassed in his implacable opposition to Imperialism in any shape or form, he is a friend of the English people. Indeed, he is more English than Indian in his thoughts and make-up. He is often more at home with Englishmen than with his own countrymen. And he is a humanitarian in the sense that he reacts to every wrong, no matter where perpetrated. Though, therefore, he is an ardent nationalist his nationalism is enriched by his fine internationalism. Hence the statement is a manifesto addressed not only to his own countrymen, but it is addressed also to the nations of the world, including those that are exploited like India. He has compelled India, through the Working Committee, to think not merely of her own freedom, but of the freedom of all the exploited nations of the world”.

Gandhi’s testimony concerning Nehru—who in Britain is commonly supposed to be ‘a Red’ or ‘an Extremist’—is strictly accurate. He was, and is now, the man in India who is best informed and whose thought is most rigidly realist about all international affairs. The half playful charge against him in his own country is that he is too much of an internationalist and not enough of a nationalist. Not only was he in Prague through the Sudeten crisis; he spent much time in Barcelona and last October, when he had returned from a month in Chungking (which the Japanese bombed several times daily) as the Chinese Government’s guest, brought by a plane spared from the few they possess, he remarked to me: “I think I know more about being bombed than anyone else in India, British or Indian”. One day it will be possible to tell of the quite extraordinary attempts made by both Mussolini and Hitler to win him over to co-operation with them. I am going to risk it, and to tell a small part of this story now. After five years in prison, in 1935 Nehru was released, to spend the last days with his dying wife. After she had died in Switzerland, in the spring of 1936 he returned to India by air. The Duce, whose previous overtures had been put by courteously—by a man who did not forget, and never will consent to forget, Abyssinia and the stifling of liberty in Italy itself—learnt that Nehru was on the plane and when it reached Rome an official of the Italian Foreign Office was waiting at the hotel, to tell Nehru that the Duce had set aside time to see him at 6 p.m. Nehru was polite and correct: expressed his sense of the honour: but flatly refused to accept the distinction. The official remained and argued. No one, he said, in any country in the world would turn down an offer such as this, from the Master of Italy—distinguished visitors from America and Europe intrigued and pressed to be allowed to speak with him, even just to look at him. He had put off a Cabinet meeting and he would be waiting. Of course Nehru must keep the appointment; it was nonsense to take this line! He himself could not afford to accept a refusal!

Nehru listened patiently, said his say quietly, and finally drew the official’s attention to the fact that the minute hand of the clock was nearing 6 p.m. Was it wise to let the Duce in for disappointment? The official in a passion flew to the ’phone and poured out a torrent of terrified speech. Next morning Nehru, who a year earlier had been in the British prison where he had wasted the best years of his prime, went on his way to India.

How many Englishmen—how many Americans—would have stood out against what was offered as an outstanding distinction? If only from curiosity and to be able to say that Mussolini had asked us to see him, and to be able to report what he looked like and said, would we not have blanketed down our convictions and conscience and gone to see him? It is only since June of this year that it has been quite the thing in Britain to say what we thought of the Duce,12 with whom we had a gentleman’s agreement.

The Duce bore no malice and for a great while refused to give up his hopes of the Indian National Congress and of Nehru in particular.

Nehru would be a happier man if he did not “react to every wrong, no matter where perpetrated”. He is one of those of whom Keats writes:

‘to whom the miseries of the world

Are misery, and will not let them rest’.

He does not consider any country “a far-off country of which we know nothing”: he feels as personal suffering all the suffering now so abundant everywhere. He was wretched after a visit to the Rhondda Valley. “It has given me a new picture of your people. I always thought that, however poor, the English could not be crushed, that they kept their independence, that they were not like us. But I have seen men being roughly treated by the police, men broken and despairing”. He has been watching the present war, in the hope that it would change from being “an imperialist war”, into a “people’s war”, and that its end would be a nobler happier Britain and a happier India.

This is why up to date there has been no Civil Disobedience. If the crisis of last year had occurred six years ago, Civil Disobedience would have followed almost as one and the same event.

India Last Autumn

A complete fog of war had fallen between Britain and India when I arrived at Allahabad by air, October 13, 1939. For example, even Inglis, The Times Special Correspondent in New Delhi, had not seen on October 20 any copy of The Times later than the September 21 issue, whereas I had seen The Times and The New Statesman of October 7; the latter contained a provocative letter by Mr. Bernard Shaw, from which excerpts had been cabled.

I had, therefore, no difficulty in seeing anyone I wanted to see; people thought I might know something about the mysterious war in Europe. The radio was telling little. One night, for example: “It is semi-officially reported from Paris that what are described as far-reaching strategic plans are believed to have been discussed at the last meeting of the French Higher Command”. Very satisfactory, to those who had hitherto supposed that what generals when they meet together commonly discuss is film stars and ballet-dancers!

But the fog seemed to go back even further. Two things in the Congress Working Committee’s statement roused in British circles an amount of questioning that for some time I could not bring myself to believe was genuine. When did H.M. Government declare that it was in favour of the League of Nations? And when had we said we were fighting for ‘democracy’?

In reply to the first question one was able to cite Sir Samuel Hoare’s too-famous speech before the League Assembly, saying that the British Government stood, and always had stood, four-square for the fulfilment of the Covenant in all its entirety. “I clean forgot about Hoare’s speech”, admitted a Member of the Viceroy’s Council. As to ‘democracy’, I could remember only that when I left England we seemed to be always hearing the word whenever Cabinet Ministers broadcast, but I could not quote verbatim. All I could say was: “Well, if we once let it be known that we are not fighting for democracy it is good-bye to all chance of help from America”. “Then you think we ought to acquiesce in a falsehood—for the sake of getting American help!”

Nine months later (August, 1940) I am beginning to wonder which of us was right.

Chapter VI

The Viceroy’s Answer

One thing that makes Indian affairs always a more or less permanent deadlock is what I must style racial segregation. Last October, not one European Member of the Viceroy’s Council knew either Gandhi or Nehru, who are known to countless people in every civilised land. I could name many other high officials in the same case. A Governor who is both able and democratic in outlook told me: “I hate the fact that I must leave India without having met either Gandhi or Nehru. I admire them greatly”.

As regards Gandhi, this is partly understandable. Gandhi (like the tiger) is royal game. Anyone under the Viceroy might justifiably fear that he was poaching if he met him, and no one would believe that a Governor’s visit to Gandhi was mere social intercourse.

A somewhat similar line of defence might be put up as regards British officials and Indians. Now that the Provinces were self-governing, the ordinary official might feel that—on the analogy of British Cabinet Ministers and the King—he should be careful to leave Indian Ministers to talk only to the Governor to whom they were constitutionally responsible. There certainly is something in this, in a land so bureaucratically run as India.

But things are far worse than they ever were before, at any rate in my lifetime. The truth is, British officialdom now knows no one. Even so staunch a friend of ours as Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru told me that social relations between British and Indians had never been less than they are now.

There was no Indian in the Viceroy’s personal secretariat, although the personal secretariat of at least some Governors had been Indianised.

There is a difficulty inherent also—in a land where social precedence counts for so much—in the vast social gulf between Viceroys and their own servants. This has been felt ever since the time of Lord Wellesley, who wrote of himself (1803), “I stalk about like a Royal Tiger, without even a friendly jackal to soothe the severity of my thoughts”. A Viceroy is usually sent from the very highest, or next to the very highest of British social and political circles.

The final touch of racial segregation is afforded by the Government’s composition, both in Whitehall and New Delhi. Last November the Secretary of State for India, the Permanent Under-Secretary, the Viceroy, the Commander-in-Chief, were all Scots: there was not a single Englishman or Welshman on the Viceroy’s Council: seven of the eleven Governors were Scots, and one an Ulster Scot: the leader of the Europeans in the Central Legislature and even The Times Correspondent at New Delhi were Scots. (The Governor of Burma also was of course a Scot).

This tradition goes a long way back. In the late eighteenth century Henry Dundas’s

“Indian and Scottish policies dovetailed very nicely into each other. He managed the Scottish vote at Westminster by the distribution of Government patronage among Scots. As a result, Scotland lost all control of its own destinies, but British India enjoyed this priceless boon of government by Scots”.13

The stock joke in the exhilarating controversial literature of that age was that unless your name was Campbell or began with Mac you had no hope of success in India.

All foreigners agree that the English are a stupid race. Yet I think they supply a certain elasticity, whereas the Scots seem to me the most obstinate devils on God’s earth. Not one inch will they budge, in battle or in politics, and I have seen them in both.

The Indian Civil Service is the world’s most majestic and coherent trade union; and its tenacity, stiffened throughout its upper reaches by Scots, is like that of the Hindenburg Line. If an occasional Welshman or Englishman were appointed to a Governorship, there would no doubt be a loss of efficiency. But would it not be justifiable on other grounds? For one thing, when we complain that India under self-government would go in for nepotism and racial preferences in jobs and posts, is not the charge at present open to seemingly devastating answer?

The Present Viceroy

The Marquess of Linlithgow cannot be said to have bridged the gulf between the Ruler of India and other Europeans. It is the custom to say that His Excellency is ‘inscrutable’, and that no one knows his mind, “except perhaps Mr. Laithwaite” (his Private Secretary, whose position is often compared to that formerly credited to Sir Horace Wilson here; people speak of “the Linlithwaite Government”).

But I am bound to say that his reputation with Indians was higher. They care nothing about social gifts, but a great deal about integrity. Mr. Gandhi said to me: “I have the highest opinion of his intellect and character. And he will promise nothing that he cannot perform. He is absolutely honest. Though, mind you, we have learnt that the honesty of Englishmen is of a very limited kind.” Gandhi proceeded to give examples of officials who had admitted to him that they could not, consistently with their duty, be rigidly truthful. We all know that this is so, especially in the last few years; we have had a bad slump in honesty. The Viceroy’s integrity, however, is of a striking kind. He has had a difficult job, not only with India but (one guesses) with Whitehall, and he has shown patience.

The Viceroy’s Statement

The Viceroy received the Congress Working Committee’s statement and proceeded to interview leaders of every kind and calibre, some of them important but others coming under the head of what Shelley calls ‘the illustrious obscure’. He knew all this, naturally, but his sense of duty and fairness made him ready to take infinite trouble. He interviewed 52 persons in all, and issued his own statement, October 18.

Mr. Gandhi called the author of the Congress’s statement ‘an artist’. There has been some curiosity as to who was responsible for the document which answered it. This is how it is written:

“I am convinced myself, if I may say so with the utmost emphasis, that, having regard to the extent of agreement which in fact exists in the constitutional field, and on this most difficult and important question of the nature of the arrangements to be made for expediting and facilitating the attainment by India of her full status there is nothing to be gained by phrases which, widely and generally expressed, contemplate a state of things which is unlikely to stand at the present point of political development the test of practical application, or to result in that unified effort by all parties and all communities in India on the basis of which alone India can hope to go forward as one and to occupy the place to which her history and her destinies entitle her.”

There are 136 words in that sentence, and the next sentence contains 88!

It would be cruel to criticise such composition; its breathlessness and lameness; its grotesque imagery, its confusion and mixture of thought. The statement left on readers the savage impression that its ambiguities were a deliberate smokescreen, under cover of which the author meant to get clean away from the point under discussion. In a way, it was a good thing it was so absurd and slovenly. It struck Indian opinion, after the first outburst of sheer exasperation, as very very funny, and the air was cleansed by happy laughter.

The statement contained two offers: (1) The British Government authorised the Viceroy to say that at the end of the war it would be “very willing to enter into consultations” with a number of people “with a view to securing their aid and co-operation in framing such modifications” in the Constitution “as may seem desirable”. (2) As a war measure selected Indians were to be allowed to help in propagandising themselves. “A consultative group . . . over which the Governor-General himself will preside . . . would be summoned at his invitation and would have as its object the association of public opinion in India with the conduct of the war and with questions relating to war activities.”

(1) was taken to envisage another Round Table Conference. The former Conference is a humiliating memory to Indians, who feel that in London they were shown at their worst, amid strange surroundings and all the opportunities of endless intrigue behind the scenes. As to (2), it was superfluous. “Indians are not fools,” said an Indian official to me. “We know all about these consultative groups. I am in one, which has just wasted three days. We have decided to do nothing for three months, after which we are to meet again. These groups are attached to everything.” A telegram can summon anyone from any part of India, and a Viceroy who interviews fifty-two people in succession has his consultative group already.

Nor was there any need to propagandise India. There was an almost passionate desire to help us if terms that preserved self-respect were granted. Mr. Gandhi had expressed himself as anxious to co-operate unconditionally. It was others, who were more troubled by the apparent ‘imperialist’ character of the war, who refused this. Nehru wrote to me: “we are not going to be caught in an unknown and dangerous adventure unless we know what the objective is and unless we can really control our policy. So long as we suspect that the aims of the war are imperialistic we shall keep far away from it, and we shall thus serve not only ourselves but others who want to pull out this war from the old ruts.” But Nehru also said:

“Some Congressmen tell you that it is not possible to make India enthusiastic on your side. But I know that they are wrong—I would guarantee to do it myself. In the last war there was a doubt about your cause, and whenever you had a defeat there was rejoicing in the bazaars. In this war you will no doubt have setbacks, and some of them may be serious,14 and there will be the old temptation to rejoice. But everyone knows your cause is ‘just’.”

The most respected British official in India said to me, “I am convinced that we have lost a tremendous opportunity.”

In Britain some indignation was expressed that there should be ‘bargaining’ at such a time. Indians did not see things that way. War, as Anatole France remarked, is “a serious matter”. It is a very great thing to ask other men to send their bodies to be killed or broken in modern war. War with Germany is an unusually serious matter (although last autumn many did not think so), and every Empire Cabinet engaged must make itself a War Cabinet. India must subordinate her pressing needs to ours.

Indian Reaction

The Viceroy’s statement found fewer friends than perhaps any statement ever issued. It was condemned, not by Congress only, but by the Liberals, the Sikhs, the Indian Christians, by several great Moslem organisations, and by innumerable leading Moslems, including Moslem Leaguers, nor did the Moslem League approve it. Sir Wazir Hassan, former Chief Judge of the Oudh Chief Court, said (October 21):

“My own feelings are of complete despair of British statesmanship, not only in relation to India’s problem of freedom, but also in regard to several international crises which were resolved in favour of aggressors and which have arisen and ended without any protest from the British Government”.

Feeling ran so high that the one Premier who had promised unconditional co-operation in the war, Sir Sikander Hyat Khan, Premier of the Punjab, the man most essential to India’s war effort, first declared (Lahore, October 11), “It is my firm conviction that India will get complete independence after the present war”, and afterwards affirmed more than once that India was sure to get ‘Dominion Status’.

There was no longer any question of even Mr. Gandhi being prepared to offer unconditional co-operation. Congress prepared to launch civil disobedience and, meeting in emergency session at Wardha, on October 21 the Working Committee pulled out its Ministries. It was a time of supreme anxiety for Great Britain, for the American Congress was then deciding whether to lift the embargo or not. What happened in India might very well turn the scale against us. Would American journalists again be cabling back accounts of unarmed men standing in line, to be struck down by the lathis of the police?

When Congress, contrary to expectation, did not launch Civil Disobedience, the relief was tremendous. They did not launch it because they thought something was at stake in this war which transcended India’s claims, and because they believed—as India still believes—in the sense of justice of the British people. They were willing to give their friends a chance to get India’s case across. They were appealing from our proconsuls in New Delhi and Whitehall to Caesar.

You who are reading this book are Caesar.

Part Two — Problems of Self-Government in India

Chapter I

The Moslems

When the government began to say (as the Viceroy did, in November and again in January) that India’s political progress depended on agreement between Congress and the Moslem League there was resentment. “We did not resign on the communal issue”, said Congress leaders. “What has the communal issue to do with the present quarrel?”

During the Round Table Conference there was a rather obvious understanding and alliance between the more intransigent Moslems and certain particularly undemocratic British political circles. That alliance is constantly asserted in India to be the real block to progress.