The Wild Sweet Witch

For Mary

Foreword

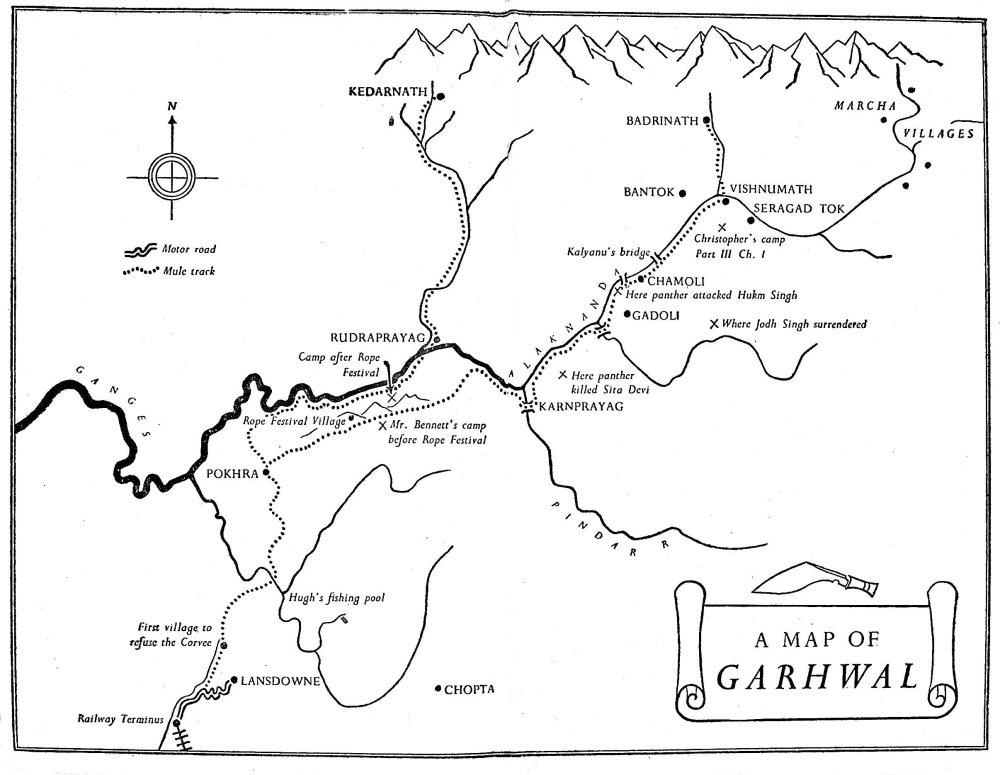

Garhwal is a real district, whose hills and people, so far as they come into this story, I have described as well as I can. Since the district is quite different from any other in India, it would be silly to try to hide it under a changed name and most of the places are drawn just as I remember them; but the story itself is fiction. None of the characters are drawn direct from any single living person, although Mr. Bennett unites in himself some of the characteristics of three Deputy Commissioners in the nineteenth century whose names are still remembered.

Readers of recent fiction about India may think that my pictures of Mr. Bennett and his successors are too kind, but one can only write from one’s own experience. Perhaps I have been lucky in the people I have known and the visitors who write books after a six months’ stay have been unlucky.

The incidents which make up the story come, more directly from experience than the characters, but they are usually based on tales heard from villagers which have been worn by time from their original shape, like pebbles in a stream, and they have been further modified to suit the main purpose. For instance, all I know about the forced labour is that there was an agitation against it after the war of 1914-18, and it was abolished. I have no idea what the Deputy Commissioner of that day thought about it nor what course the agitation took. There was certainly no Jodh Singh. Again, there really was a panther who killed human beings once or twice a week for some years; the villagers did think he was a man by day, who turned into a panther at night; and the Deputy Commissioner of the day did take a man into protective custody to prove he was not the panther. But my knowledge is based on hearsay; the true story of this panther is, I believe, being written by Major Jim Corbett, the author of Man-eaters of Kumaon, who eventually shot him.

The word I have translated ‘warlock’ really means a person who may turn into either a panther or a bear and some of the stories I have heard seem to indicate that the same person may turn into either and does not even know which form he is going to take when he starts his spell or incantation.

I have never cared for what Peter Fleming calls the ‘nullah’ school of writing, and expect other people to dislike Indian words they do not understand as much as I do the ‘m’bongos’ and ‘b’wanas’ in books about Africa. I think there are only three Indian words in this story: kukri, the heavy Nepalese chopping knife, which has been made familiar by the doings of Gurkha and Garhwali troops in two wars; tahsildar, a magistrate and revenue officer, who in the hills is a police officer as well; and patwari, a junior revenue official. He too in the hills is also a policeman.

Names, however, cannot be avoided, and the easiest way of explaining the pronunciation is to say that vowels are as in Italian, except the short a which has the sound of u in the English word butter. Thus Kalyanu is pronounced Kull-yah-noo, the first syllable rhyming with hull. ‘Garhwal’ is very difficult to pronounce well, but for all practical purposes the first syllable rhymes with ‘her’, and the second with ‘marl’. By the same rough standard, ‘Jodh’ may be taken to rhyme with ‘goad’.

I have a clear conscience about crops, states of the moon, and seasons; but the feast of lights mentioned in Part Three would really have come a few weeks earlier in relation to other events, and I suspect that the rope festival really took place in the spring, in order to fertilize the millet and maize crop. But it fitted this story to relate it to the winter crop of barley and I doubt whether anyone can say this is wrong, because there is no one living who has seen it.

Part One

The Uprooting, 1875

Every one in the hills knows that when the snow has melted and the flowers are in their first glory, the scent in the high pastures is so strong that it makes a man drunk and he is likely to do strange things and wake with a headache. Kalyanu knew the feeling well, for it was his custom every year to climb many thousands of feet to the summer alps and to stay there with the sheep and goats for the lambing. But now he was in the fields below the forest where the homestead stood; and yet it was the same constriction of the throat and lightness in the head, the same impulse of wild unreason, that rose and choked him as he stood looking at his field of ruined millet.

As soon as he had come down from the pastures, he had been round the fields to see how his brothers had managed while he was away. It was a hard life they led, here between the mountains and the river, and they had not much reserve if a crop failed them. The autumn millet fed them for most of the year, and they added to it any barley they were lucky enough to get if there was good snow or rain in the winter. But the millet was their life, and here were the best fields ruined by a bear. Rage filled him; it swelled in his chest and head, a drunkenness of rage as suffocating as that other drunkenness of height.

As the worst of it passed and he became conscious of more than blind fury, he spoke aloud:

‘The bear must be killed,’ he said.

He looked at the sun. It would soon be behind the mountains to the west; daylight is short in the high steep valleys. The bear would come again when the sun had gone and he must quickly get his brothers together for the fight. No one could be certain that the bear would come to the same field, but there was a chance. He looked at the damage, and the drunkenness rose in him again when he saw how the beast had rolled in the crop after eating its fill. But he fought it down and looked for tracks in the moist soil which was never wholly dried by the brief warmth of midday. It was one bear, only one. It would be an old strong male. It would come again, that night or the next or the one after; they must wait every night till it came and then they would kill it. He went quickly down the hill to fetch his brothers, planning as he went.

His problem was not an easy one. Weapons were his first thought. There was not much iron in the upper hills of the Himalayas in the year 1875, because every ounce had to be carried up from the plains on the buyer’s back and the journey took twelve days. As the buyer had to take his own food for the journey too, the less iron he carried the better. What there was, soft untempered stuff, would not take an edge and was most of it beaten into short blunt sickles or trowels. Wood and stone were the two materials of which there was plenty and they were used for almost every purpose. The only arms Kalyanu possessed were one degenerate kukri used for beheading goats, one axe, and several heavy wooden poles. The kukri was really quite unsuitable for a fight with a bear. It was small and involved coming to very close quarters before it could be used. The axe was better and would be invaluable in the last stage, but it was short and clumsy. Kalyanu had decided before he found the first of his brothers that they must stun the bear with poles and then use the axe to fhish him off.

The four brothers were all working in the fields near the homestead and it did not take long to find them nor to collect their heavy poles and the axe and kukri. They started at once on the climb back to the damaged field. The path was one they had made themselves in their goings and comings to their fields, and to the forest above the fields where the women went to cut grass and collect sticks, and where they drove the cattle to graze. The way led first through the home fields, little shelves of ploughed land a few yards in width, with a slanting scramble after each shelf up a bank, about the height of a man, faced sometimes with stone, sometimes with the natural turf. The twisted triple ears of the green millet near the farm, like the plaited tails of tiny shire horses, were beginning to turn yellow for the harvest; farther up the patches of red millet were already a deep madder, ear and leaf and stalk alike. The air was moist with the fruitfulness of autumn and the scent of vegetation was heavy.

The path left the fields and struck up slanting across a long hillside too steep for cultivation, deep in grass which the women would cut before it was buried by the snow. But it was easy walking because the feet of themselves and their goats and their ancestors for generations had worn a firm ledge, seldom as much as six inches wide, but not difficult for anyone who did not think of the depth below. For the almost precipitous grassy side gave way farther down to a sheer rocky scarp, which fell away in cliff on cliff to the river, boiling in ice-fed spate in its narrow channel. The steady roar of tormented water and rolling boulders made a background to every other sound that Kalyanu and his brothers heard, although the river was thousands of feet below them.

The way led below a sheer rock face with a spring at the foot and then turned to zigzag directly upwards to the less extreme slopes which lay at the top of the cliff. Here the labour of their fathers and grandfathers and themselves had driven back the pines and gradually cleared a patch of snaky terraced fields, sloping outwards between rocky walls, fields a few feet wide that nothing could have ploughed but the little mountain bullocks as high as a man’s waist, and that no one but a hillman would have thought worth the heart-breaking labour. But on this side of the river there were only two patches of ground where the slope was not so steep as to forbid even this hard-won cultivation, one near the homestead and the second up here, where the bear had rolled in the millet.

The sun was already behind the mountains as the brothers climbed the hill, but there would be reflected light from the sky for some time. The fight had to be very carefully planned, because one man with a pole is no match for a bear and if the bear was able to attack one of the brothers alone, that one would probably be killed. Kalyanu was thinking hard as he climbed. If all the brothers were close together from the start, hiding behind one rock, the bear would probably get away. A bear can move fast for a short distance and it would not stay to fight five men if it saw them all close together in a group. But if the brothers surrounded the field and were too far apart, one of them might be left to face the bear alone. It must eventually make away up hill, towards the forest, for there was a sheer drop on the lower side. A subtle plan was needed, based on the lie of the ground.

The three fields that were damaged were at the top of the patch of ploughed land and from Kalyanu’s point of view at present they were well placed, for there was only one natural line for a retreat to the forest above, and that was fairly narrow. On one side was a bluff with a rock cliff fifty feet high, up which not even a goat could go, and on the other the debris of some fall of rock in forgotten times, huge fragments as big as a cottage, over which a bear could scramble, but which he would not willingly choose as his path. His natural line would be between the bluff and the fall of rock. He could, of course, go down and traverse below either of these obstacles, but he would not do this unless he realized that he had something formidable to face. And this was unlikely, for firearms were almost unknown and as a rule the men of the hills feared a bear more than the bear feared them. Once the bear was committed to the way between the cliff and the fall of rock, he would not easily be deflected. The plan must, therefore, be to make him start on that path, and then to take him in the narrow place, all arriving there at the same moment.

Kalyanu did not formulate this reasoning even to himself. He certainly could not have put it in words, but by a swift subconscious appreciation of the nature of the ground and the mentality of his enemy, he saw that it was the best course to take. And since his brothers gave him unquestioning obedience, he did not need to explain his reasoning to them. He hid two of them among the rocks to the east of the narrow place and two in the bushes in the thick shadow below the cliff on the west. He himself would be farther down, below where he thought the bear would be, and it would be his first task to make it move towards the narrow place. He explained to his brothers what they had to do. They were to lie still, even when they heard him shout. He would not show himself when he first shouted, but would try to make the bear think it had more than one man to deal with, so that it would start for the narrow place, but it must not be frightened, it must be slow and unhurried. Only when Kalyanu showed himself and shouted a definite word of command—‘Strike’—were they to leap out from their hiding places and rush upon the enemy. And then they must make sure to arrive all at the same moment. They must not lose their heads in the excitement and rush in without thought. He made each of them repeat what he had to do.

The waxing moon rose early, but it was some time before it cleared the eastern hills and shone on the fields and rocks of Kalyanu’s upper farm. The forest above the ploughed ledges was of blue pine; the trees nearest to the fields glistened with little points of light, but the mass of the forest made a black menacing shadow. Inky black were the shadows below the rocks and among the thick bushes at the foot of the cliff. The silvery light on the narrow fields seemed clear as day by contrast, but it was deceptive. You could not distinguish detail, and it was the shadow rather than the object that could be seen. Black and silver, forest and cliff and rock, the stage was set.

Kalyanu waited with fast-beating heart, a sick feeling in the stomach. He strained his eyes to see their enemy. Surely that shadow had not been there before. It was just the shape of a bear. It was very still. No, it was moving; a tiny movement. It looked different; it had moved as he blinked his eyes. It was the bear. Wait and see which way it goes. Wait. Wait. No, it has been still too long. No, it is nothing, a rock. Things look so different in the moonlight. Quiet, more waiting, and then again the heart pounds, the breath comes quick, the palms of the hands are wet on the polished wood of the staff, at a stone rolling down from above; the bear must have dislodged it. Wait again; wait and see; no, it was nothing.

Disaster might have overtaken the brothers if they had missed the bear that night and had tried a second night with senses dulled by lack of sleep and the boredom of waiting. But they were lucky. The bear came early, while they were still keen and alert, keyed and poised by Kalyanu’s talk, their eyes bright, their bowels still conscious of the nearness of danger. The black bulk rolled forward in the moonlight, black as a moving shadow. Kalyanu waited till it was well into the field and then he yelled. He did not show himself, but shouted and moved from one bush to another and shouted again; he beat the bushes, threw stones at other bushes, and rolled boulders down the hill. The bear stood still suspiciously; then slowly it began to move uphill towards the narrow place. Still Kalyanu did not show himself; he waited, watching, forgetting to breathe, judging his moment; then he shouted: ‘Strike!’ and ran with all his strength and fire for the narrow place. The four brothers sprang from their tense muscles and dashed forward, hurling insults at the bear.

It was perfectly timed. The four younger brothers reached the centre of the narrow place a fraction of a second before the bear; Kalyanu was close behind, in a position of great danger if it should turn. But it did not turn; it swung clumsily but with incredible quickness to its left towards the cliff, meaning to pass between the two brothers coming from that side and to maul both as it passed. But the men it had to deal with were not trying to get away as it had expected; their stout poles swung high above their shoulders and came down with all their force, almost in the same second as those of the two on the right. Three blows fell on the head and neck and the fourth, that of the brother on the bear’s extreme right, on the backbone. And at the same moment Kalyanu flung aside his pole and made his axe bite deep into the back above the root of the tail. Such a volley of blows, all at once like a clap of thunder, stopped the bear for the blink of an eyelid, but he shook his head and rose on his hind legs to strike right and left with the curved claws of his forepaws. But again that shattering volley of four blows fell on head and shoulders and a second time Kalyanu struck with his axe and this time the axe reached the backbone. The bear fell; at once all five were on him, yelling wildly, striking again and again till their poles were splintered and broken. The bear lay stunned and battered; with all his strength Kalyanu swung the axe and split its skull. He drew the kukri and cut its throat.

‘He’s dead,’ they said.

‘He’s dead!’

They could not believe it. They were silent, looking at each other and panting. Then they all began to talk at once.

‘Did you see how I hit him the moment he turned our way?’

‘Well, he’s dead now, and he won’t roll in our crops again.’

‘That was a fine blow Kalyanu caught him with the axe!’ And so on. At last Kalyanu stilled the chatter and said:

‘Let us drag this sod of a bear out of our field into the forest and leave him to the vultures. Then we will go home and eat. We will kill the home-fed sheep. And we will eat raw game. And when we have eaten we will dance. We will dance Baklitawar Wins.’

They did certain things to the corpse and then they dragged it out of the field and they went back down the little twisty path to the homestead. The moon silvered the grass on the steep side below the bluff, as the wind sighed over it in a long ripple, like a caress on the skin of a panther. The wind sighed again and the blue pines breathed deep in reply. The roar of the torrent below rose to them faintly and the wind sighed in the pines, the five men chattered of their triumph, but behind all trivial sound, behind the roar of the torrent, was the deep positive silence of the mountains, the silence, and the silver of the moonlight.

The chatter broke out in a fresh spurt of excitement when they came to the little cluster of houses where they lived, a stone-paved terrace with circular paved pits for treading out the corn, and round the terrace little stone cabins on three sides of a square, some for men and some for beasts. The women heaped up the fire and they dragged out the home-fed sheep. It has been in the dark and fed on grain for six months. The grain made it fat; it was kept in the dark so that the sun should not melt its fat. Its feet had grown so that they curved up before it like fantastic medieval slippers. Autaru, the second brother, led it up to Kalyanu. There was no Brahman in the little community of Bantok, but Kalyanu was priest of the godling they propitiated from time to time, a power who had ruled over this hillside before the Hindus came up from the plains. The godling lived in a tiny stone house at the foot of a cedar tree. They led the sheep before him and marked its forehead with a daub of colour and a few grains of barley. Then Autaru seized the sheep by the horns and leaned back, stretching the neck while another brother held the hind-quarters. Kalyanu struck once with the kukri and Autaru staggered one pace back with the head in his hands. A spurt of blood fell on him and he laughed, and they all laughed at him. They cut the sheep to pieces without skinning it, and singed the raw meat in the flames. Then they ate it with handfuls of salt. The liver they did not even singe in the fire but rolled little pieces of it in salt and red pepper and ate it. This is ‘raw game’; for in Garhwal all meat is called ‘game’.

They piled up the fires higher and stuck torches of pinewood round the paved courtyard. Then they began to dance the dance of Bakhtawar Wins. There was a family of aboriginals, the dark-faced Doms, who lived farther down towards the river and worked as the serfs of Kalyanu and his brothers. One of the children had gone to fetch them as soon as the triumphant party returned. They had brought the drums, one a great vessel of copper shaped like an egg with the top cut off, the severed end bound over with stout buffalo skin, the other smaller, with a narrow waist, a percussion surface at either end, bound with thinner goatskin. The drums were beaten with a curved and polished stick held in the right hand; the second man played also with his fingers and the butt of his left palm on the reverse end of his small tenor drum. There was no other instrument but the drums, and so no tune, only the cadence of the voice singing a ballad and the odd exciting syncopated rhythm of the drums, quickening and quickening to intolerable broken speed, dropping again to a slower throb, throbbing and pulsing in slow broken rhythm, quickening again, pulsing faster and faster at a climax in the story.

There was silence and silver moonlight on the cliffs and the hanging bulk of the hills, but in the paved yard before the houses the flicker and waver of torches and the broken pulse of the drums and a man’s voice singing. The figures moving in a circle were short and square, the woollen blankets that they wore looped round their bodies and over their shoulders like a plaid, accenting the angle of the shoulder. They stamped and bowed in the dance, their arms rose and gesticulated, as they circled between the torches. The little circle of fire and human joy was as small as one star among the myriads of heaven.

The ballad to which they danced was the story of a king from over the passes in Tibet who crossed the high range and came down with his slant-eyed men into the valleys of Garhwal. They came with their felt boots, their barbarous furs, round copper shields studded with turquoise and silver, with spears and swords and bows, and they were very many. But Bakhtawar called together the people of the valleys and led them against the invaders. When they told him that the odds were against him, for the men of Garhwal were few and poorly armed, he told them that this was a land beloved of the gods, where the sacred Ganges rose, and where the gods had played and journeyed when the world was young; the gods will help us, he said. And sure enough, when they came close to the armies from across the mountains, the gods sent on the Tibetans a madness, that drunkenness that comes in the high pastures when the flowers are in bloom. They ate stones and grass and snow and turned their weapons upon each other; and the people of Garhwal fell upon them and killed many of them and drove the rest back over the passes. So to this day they dance the dance of Bakhtawar Wins to celebrate victory.

The dancers are first the people of Garhwal, marching up the narrow valleys to unequal battle; and then in turn they are the Tibetans on whom the madness has fallen. They become possessed by the gods and the drums quicken and quicken again, till it seems beyond belief that nerve and muscle can keep up the speed, and each dancer twirls away in a wild pas seul, twirling and spinning till he falls breathless and dizzy. Then on hands and knees he fills his mouth with grass or stones, and foaming and champing joins the dance again, till at last the rhythm drops and all sink exhausted to the ground. Then again the steady throbbing approach of Bakhtawar’s army, and again the drums quicken to the climax of action and victory and defeat.

The drums died, the torches burnt low, the serfs went back to their hovels below and the people of the homestead turned to sleep. Kalyanu was happy. Like Bakhtawar, he had triumphed over impossible strength. He had earned his rest. The little homestead clung to the cliff’s edge and there was only the silver moonshine, the roar of the torrent below, the sigh of the wind in the pines and the deep silence of the mountains.

II

The mood in which Kalyanu and his brothers danced and feasted after killing the bear lasted for some days. They had indeed done something worthy of note. As a rule the people of the high valleys looked on the damage done by wild beasts as an act of the gods, something against which it was little use to fight. They took some precautions, just as they went through certain ceremonies to avert calamity, but with no very fervent belief that anything would come of it. They put up scarecrows and primitive booby-traps and, if things got too bad, would build themselves a little hut raised high above the ground on poles and in this would watch all night with the object not of killing but of scaring the marauder; but that was as far as they usually went. Gun-licences were rare and were usually given to pensioners from the army or to the descendants of the barons who had ruled the land for the Rajas in the days before the Gurkhas swept over the hills and conquered the country. And if Kalyanu had asked for a gun-licence, which he was not so presumptuous as to do, he would certainly have been told that he was not the most important person in his village, no account being taken of the fact that the rest of the village was on the other side of the river and the nearest bridge was thirty miles down stream. The bow was forgotten, though it had been the weapon of the heroes of Hindu story and ballad. And for some strange reason the pit-fall was not used. The truth was that the hill folk were not a hunting people and knew little of the ways of beasts.

So it was a great thing to have killed a bear with clubs and an axe. Kalyanu woke next day with something of the exaltation of a young man successful in his first love affair. He regarded the world with the same feeling of confidence in himself and mastery over external incident; he could shape events as he wished them and make others dance to his piping. And just as the happy youth feels himself irresistible to all women, so Kalyanu believed that he had nothing more to fear from wild beasts. Bears were easy.

This confidence and self-satisfaction were still with him a week later when he decided to climb to the upper patch of ploughland and see how the crops were ripening. In the fields round the homestead, his brothers and the women were all at work, getting in the yellow millet. Men and women alike moved stooping through the crops, reaching out the left hand to gather together a bunch of stalks, cutting with a stroke of the blunt sickle in the right hand; there was none of the orderly division of labour that went with the work on an English farm at the same period, no sweeping line of scythes with the women picking up. Each worker drove his own path into the crop and collected the fallen corn when there was a load he or she could conveniently manage; each carried it on his own back to the homestead. Kalyanu regarded their activities with satisfaction and thought of the work still to be done. The snow had already fallen on the high pastures in a light powdering that would melt by day. Up there the ground would freeze hard every night and the clefts and corries where no sun came would gradually fill with snow; but it would be two months yet with any luck before it would lie on the upper fields. There would be time to fhish the harvest in the lower fields, then to get in the millet from the higher; then to plough into some of the upper fields the rotted bracken that had been stored during the summer and sow the barley before the snow covered it. Next would come the ploughing and sowing of the lower fields. It was a great convenience that everything on the upper farm was so much slower; one could cut later and sow earlier up there; the labour force at Kalyanu’s disposal would not have been enough to deal with the same acreage if the land had been all at one level and the crops had all ripened at the same time.

He turned from the busy scene in the fields round the homestead and set his face to the path leading to the upper farm. He climbed easily and quickly; indeed it was hardly climbing to him, for his muscles were so attuned to rough paths on the hill face that they would have been more quickly tired on the level. But he had never walked on the level.

Kalyanu had no ears for the roar of the river below, no eyes for the scene he knew so well. His thoughts were on practical matters, the harvesting of crops and the work he should set his brothers to do. To an observer on the hillside beyond the river he would have seemed a minute dark point moving steadily across the grass slope below the bluff. Even the ploughed land below him made only a tiny patch of colour against the immensity of the hillside. Its snaky terraces, the crimson of the red millet, the yellow of the green millet, the brilliant orange of the drying heads of maize, were touches with the point of the brush, hardly to be picked up by the eye in the vastness of rock face, grass slope and forest. Grass clothed the hill where it was not sheer rock; forest poured into every corrie, glen or hollow where a tree could stand. Below the homestead were long-leaved pines, the light sparkling on their dancing upturned needle-points, their airy glitter interspersed with the darker masses of cedar or contorted oak scrub; higher, the blue pine turned its closer darker fingers to the sky with the same exultation. Even where the trees could grow, the line of the ground was nearer the vertical than the horizontal; it was a landscape crazily tip tilted out of the plane familiar to the world of men and the tiny evidence of man s presence could hardly be distinguished against those impending precipitous masses.

When Kalyanu reached the first field he plucked an ear of millet and rubbed it between his fingers to see how it was forming. He was pleased at the progress it had made. It should be possible to start cutting this patch from the bottom upwards as soon as the work below was ended. He climbed up from terrace to terrace, appraising the crop in each narrow shelf. Half-way up he stopped and stood, gazing at the ruins of one field where a bear had again eaten its fill and rolled.

The anger he felt this time was quite different from that of a week ago. This was no surging of uncontrollable fury, because he no longer felt helpless. He knew how to deal with a bear. He would show the swine. He went quickly over the remaining fields, to see the extent of the damage, and he looked at the footprints. Not so large a beast as last time. Probably a female. His confidence needed no strengthening but his contempt was increased. He followed the tracks up through the crops to the narrow place at the top, where the first bear had been killed. This was where the female too had come in from the forest. Then he turned to go back and fetch his brothers.

It was a pity that Kalyanu did not examine the tracks more carefully or apply his mind more thoroughly to the problem. Had he done this, he would have seen that the tracks did not return to the forest by the narrow place, as they had come in. He had hunted heel, following the tracks back in the direction from which they had come; but though they came in by the narrow place, they went right through the crops, going on, not back. After eating and rolling, the bear had wandered downwards and westwards, passing out of the cultivated patch below the cliff that formed one flank of the narrow place. If he had noticed this, Kalyanu might have remembered the thicket of wild raspberries that lay beyond the plough on that western side. If he had troubled to think how a bear lived, it would have occurred to him that it must find much other food besides his crops and an occasional goat or bullock. He might then have reflected that this beast must have enjoyed the wild raspberries and that where a bear has gone once, it may go again; and had he thought thus, the story of his life, his son’s, and his grandson’s, might have been changed. But the Himalayan peasant is unobservant of the ways of beasts and birds except as they affect him directly. He does not even know of the strange habits of the cuckoo, whose word of fear rings through his hills in May and June just as it does in England. Kalyanu assumed that this bear would come in by the narrow place and could be made to go out by the same way, just as the first bear had done a week ago. He did not hesitate but went at once to fetch his brothers.

The five men stopped work in the fields, leaving it to the women to go on till dark, and climbed up the hillside once more to the ambush. But they did not come as they had a week before, full of wonder at their own daring, breathless, with a queer empty feeling in the bowels. They were only a little keyed up by the thought of what they had to do. They could joke among themselves quite naturally, for they knew now that bears were easy.

Kalyanu arranged them just as he had done before and they took up their stations. The moon had not yet risen, so that waiting should have been more nervous work than last time. But the tension that had made the heart pound at every moving stone and crackling leaf had gone when victory was achieved and, far from being on edge, as the night wore on, the younger brothers were inclined to doze. Kalyanu being separate from the others did not know this, but Autaru, the second brother, had to speak several times to his companion, the youngest, to keep him awake. They had all worked a long day in the fields.

No bear came that night and it was a weary and dispirited party who came back to the homestead in the dawn. They worked badly in the fields that day and when Kalyanu told them they were to watch for the bear again, Autaru was the only one who did not grumble. But there was no question of disobedience and they hid once more in the appointed places, Kalyanu agreeing, however, at Autaru’s suggestion, that one of each pair of brothers should sleep.

The moon had risen and her silvery light made long inky shadows below rocks and terrace walls, when, an hour after this watch began, Kalyanu rose carefully to his feet, taking care to make no sound. He glanced over his shoulder to the east and saw the pines on the next ridge cut out in rigid black silhouette against the growing radiance; then turned again to look at the fields before him. As he looked, he stiffened in sudden attention. There it was. Yes, there was no doubt. There was the bear, right in the middle of the crops. That shadow had not been there before; it was moving slowly, very slowly, but undoubtedly, moving, as the beast nosed here and there, making up its mind where to begin.

For about ten heart-beats Kalyanu was flustered. The bear was below him. How had it got there without his knowledge’ Had it crept past him in the dark? It seemed now to be moving upwards; was it already retreating? But the moment of indecision passed. However the bear had got there, whatever irrelevancies it had introduced, the original plan must stand. It was moving upwards. He would wait till it was level with him and then he would hurl rocks and shout, and it would make upwards for the narrow place.

The bear moved very slowly and Kalyanu’s patience began to wear thin. He was very short of sleep; and all the time this sod of a bear was spoiling his crops. He did not stick to his decision to wait till it was level with him. The bear was still on a terrace lower than his own when he let out his first yell and began to throw stones at the bushes and send them crashing down the hillside.

The bear raised her head at this sudden commotion and began to move away, slow and unhurried, for she was disturbed, not frightened. But she did not go towards the narrow place as Kalyanu had expected. She went back the way she had come, towards the wild raspberries, downwards and westwards. Kalyanu sprang to his feet.

‘Strike!’ he shouted at the top of his voice, and ran after the bear in a frenzy lest she should escape and the hours of waiting be wasted. He sprang down from the top of a terrace-wall into the field across which the bear was moving with rolling unhurried gait. He swung his pole and brought it down with all his strength on the hairy black hindquarters. The bear turned with incredible speed; Kalyanu struck again with his shortened staff as she came at him on all fours, but quite ineffectively; the bear’s quick lunge with mouth and paw went home. Her right paw broke his left leg below the knee; her teeth crunched deep in his right thigh.

As Kalyanu fell back at the foot of the terrace wall, Autaru arrived at the top with a yell and struck downwards with his staff at the beast below. It was a blow into which he could put no strength, for she was too far below him, and in a blind red fighting lust he sprang down beside her. His blow had been just enough to distract the bear from Kalyanu and to infuriate her. She rose on her hindquarters and struck with both forepaws a fraction of a second quicker than he could. Her left stripped the flesh from the side of his face and glanced off his shoulder; but before he could feel the agony her right fell with its full force on his head, crushing the skull and breaking his neck.

The youngest brother had been sharing the watch with Autaru in the bushes below the cliff and had been asleep when Kalyanu first shouted. He was only a few yards behind when he saw his brother drop lifeless, but he was fully awake by now and he acted with sense and courage. He did not leap down at once to the bear’s level, to drop almost into her arms as Autaru had done, but moved off a few paces, dropped to her level and approached her warily, poised on his toes, ready for flight or fight. The bear had hardly noticed him, for she was still wholly unafraid, and was actually sniffing at Autaru and considering his possibilities as a meal, when he struck. Her lunge towards him with curved left forepaw was made almost as one might brush away a fly; she returned to her interest in Autaru. But her hooked blow had done all that was necessary; the youngest brother had sprung back and had dropped his staff as a guard, but the bear’s strength and quickness were such that the staff was torn from his hands and broke his shin-bone where it struck him. He pulled himself away from the enemy with his hands, trailing his useless leg.

The third and fourth brothers arrived as the youngest fell. They had run as fast as they could and were wildly excited. They too would have flung themselves at the bear, no doubt with the same result, if Kalyanu had not spoken. But lying there sick with pain, he still knew what was happening and from the shadow below the terrace wall had seen the fate of his two brothers. He heard the others shout as they came up and called up all his strength to cry:

‘No! Do not fight! You must look after us. Do not fight!’ Then he fainted.

The two remaining brothers pulled up at Kalyanu’s voice. For a second they hesitated, but they were used to obeying Kalyanu, and once they paused a strong natural inclination came to the aid of his instructions. They shouted abuse and threw stones but kept their distance. The bear paused, grunted, then slowly made off towards the wild raspberries. The two brothers returned to pick up their wounded and take home the dead.

The youngest brother had a cracked shin-bone which needed nothing but rest. Kalyanu’s case was more serious. His left leg required to be set before nature could begin the work of healing; and more serious still was his mangled thigh, with multiple wounds from the bear’s teeth. He and his brothers knew well enough that a wound can go septic, but their only means of preventing this was to apply cow-dung to exclude the air and in this method they had, rightly enough, no great faith. Kalyanu lay tossing in agony while the two brothers who were still whole debated with the women of Bantok what they should do. No one really had any plan, until one of the outcast Doms mentioned that the day before he had met another Dom from ten miles down the river who had come their way in search of a stray goat. He had heard that the Deputy Commissioner would soon be coming to camp on the other side of the river, near the bridge thirty miles down stream which was their only link with the outside world. Everyone’s face lightened; they were not used to responsibility but to doing what Kalyanu told them, and here was someone else on whom the responsibility could be placed.

‘We will take him to the District Sahib,’ they said. Kalyanu was lying on a bed, made of tough oak roughly shaped with the axe and strung with hemp string they had twisted themselves, but it was too wide for the paths they would have to follow. They must make a litter hardly wider than their own shoulders or it would catch on the cliff walls and throw them all over the edge. The women set to work quickly to make a hammock which could be slung from one stout pole, whilst the two brothers worked feverishly to get in what they could of the millet and to leave the farm in such trim that the women could manage without them. Ten or twelve miles on a hill path is a good day’s stage for a loaded man, but they could not afford to take three days to reach the bridge. They must hurry, because they had to get back to see to the harvest and because if they were to save Kalyanu he must be in better hands than theirs as soon as possible. And before they went they had to burn Autaru.

It was not till the morning of the second day after the disaster that they started, taking with them food for three days only. They could get more on the other side of the bridge and they took with them some of their precious store of silver, a hoard into which they usually dipped twice a year to pay their few rupees of land revenue; once every year or two when one of them went across the river and down towards the plains to Chamoli to buy salt and iron; a few times in a generation to buy a bride. They started very early, after a drink of milk and no more, meaning to get as far as they could before they stopped for food. The women watched them move away, their reddish-brown legs naked to the thigh, their sturdy bodies square in the dark homespun blankets draped across the shoulders, Kalyanu swinging in his hammock between them. Then the women turned to get on with the work of the farm, the feeding of the children, the animals, and Darshanu the youngest brother, and the harvesting of the millet, their life-blood for the winter.

The path the brothers had to take followed the river and, since the river for most of its course ran in a precipitous rocky gorge, it was not an easy path. It went down to the river for an easy crossing of a tributary torrent where there were stepping stones, renewed every year after the autumn spates, and then across the shingly debris brought down from the hills in the course of years. The roar of the river here was deafening. You had to put your mouth to a man’s ear and shout to make yourself heard. The water was milky-green with the ice-ground dust of glaciers and melted snow; it swept and churned and stormed, spouting high where it dashed against a bastion of the cliff, breaking with the shattering weight of Atlantic rollers over a rock in midstream, rolling and grinding the boulders in its bed, a stream of ceaseless, furious energy, seeking the centre of the earth with swifter force, but the same remorseless purpose, as the upthrusting green of trees and grass and corn.

Then the path went up, zigzagging up a narrow edge between two arms of the tributary torrent, then out on to the face of the sheer rock cliff over the main river, following a crack that led up and up for two thousand feet; then on to a long grass face, so steep that if one stretched out a hand to the bole of a pine below the path, the fingers touched a point twice the height of a man from the roots. Across this face the tiny track made by the feet of goats and men lay like a single hair. Down again, to a tributary crossing and a stretch of shingle; up, to go over another bluff with an impassable face; a long, long, tiring journey in which the mind after some miles could not disentangle the steady succession of cliff and torrent, corrie and grass slope, rock and pine.

The brothers kept going all day, except for a halt in the middle of the morning to eat. They had fresh water to drink at every torrent, ice-cold, and they were in hard condition, but they were very tired by the evening, for they had covered twenty miles, a long march over such country and with such a load. They gave Kalyanu water; he wanted nothing else; they put him by their side on a bed of leaves in the shelter of an overhanging rock, much used by goats and shepherds, where they rolled themselves up in the blankets that had covered their shoulders by day.

They reached the bridge at midday on the third day after the disaster. Near this point on the northern bank, there was a village, not an isolated homestead, for a larger tributary had made a valley in which there were slopes that could be terraced and ploughed. Here the banks of the river approached each other in two leaning cliffs, on each of which there was a convenient ledge on which a man could stand. From each side had been thrust out three pine trunks lashed together, the butts firmly wedged in hollows carved deep in the cliff face, the angle of the ledge pushing them steeply up, so that the space between the tips could be bridged by a pair of lashed trunks. The drop from the bridge was two hundred feet to the frenzy of the milky torrent below. It was not easy to walk over the two pine trunks with such a burden as Kalyanu in his hammock, but the two brothers did it. Fortunately Kalyanu was conscious at that point and they made him understand that he must lie quite still, for a sudden movement would destroy them all.

When they got him over, they looked at each other and grinned.

‘That was worse than the bear,’ said Amru, the elder.

They went on to the first village and began to ask questions. It was true. The Deputy Commissioner’s camp was only five miles away up the hillside. In two more hours, his tents were in sight, but their hearts sank. They would have to talk and explain, to superior people, who would laugh at them because their hair was long and their speech barbarous. But their luck had turned. They met the District Sahib himself as he was coming back to camp and he stopped to ask them questions.

At first they were speechless, shifting from one leg to another. Then Amru said:

‘Lord, it is our brother. It was a bear. We have brought him to you.’

And after more questioning at last the strange man understood them. His face was strange, sharp and light coloured, but kindly; still more strange was his speech; but he had understood. He would look after Kalyanu. They could go back to the farm.

III

Mr. Bennett, the Deputy Commissioner of Garhwal in 1875, was an amateur surgeon and physician of some repute. His methods were simple and usually drastic but they suited the people with whom he had to deal. Castor oil was the basis of his physic, warm water and carbolic of his surgery.1 With a people who did not wash much and lived in highly insanitary villages, the moderate degree of surgical cleanliness he was able to achieve worked wonders, for, when it was released from the great majority of the foes it was accustomed to deal with, the injured flesh flourished and clove together with startling rapidity.

It did not need great skill to see that Kalyanu’s left shin-bone would have to be set and Mr. Bennett set it and bound it to a splint of oak, an unshaped branch that happened to be the right shape and size. The bitten thigh was more difficult. The bone did not seem to be broken but was probably bruised; the flesh was terribly lacerated. There was really nothing to do but to clean up the oil and cow-dung which the people of Bantok had applied, wash the wounds generously with hot water and carbolic and tie them up again, continue the treatment, and hope for the best.

So Kalyanu’s pole and hammock joined the considerable assemblage that moved round with Mr. Bennett’s camp. Rest in one place would of course have been much better, but the business of the district could not be held up for one man and Mr. Bennett could not trust anyone but himself to look after the patient. The addition of a load that was now usually carried by four men made little difference to his arrangements, because his tents and bedding and gear and that of his many servants were carried by the people of each village to the next halting-place. This was an ancient feudal service due to the Rajas which had been continued by the Commissioners of Kumaon because there was no other way of getting about. Kalyanu was moved every two or three days and the journeys were not pleasant, but then he was not used to anything pleasant and he was being looked after better than ever before in his life. Mr. Bennett’s orderlies were charged with the duty of feeding him at Mr. Bennett’s expense and, being hill-peasants only one degree less unsophisticated than Kalyanu himself, they did as they were told. It never entered their heads to underfeed him for their own benefit, or to overcharge their master. Once a day Mr. Bennett himself came and took off the bandages and washed the wounds. After the first day or two, as he began to mend and his mind grew clearer, Kalyanu tried to struggle to his feet when this strange ruler came to see him but it was made clear to him that this was forbidden. His first feeling of surprise and fear at being waited on by someone who was practically a king was gradually replaced by veneration and a deep devotion. If it is love to wish ardently for an opportunity to serve and be near the object of one’s devotion, then Kalyanu loved Mr. Bennett.

Mr. Bennett in his turn felt an increasing liking for the man who grew to health under his care. For a generous nature, there is a natural inclination towards affection for anyone to whom a kindness has been done; and to this was gradually added an interest in Kalyanu himself. It was difficult at first to get him to talk. ‘Yes, lord,’ and ‘No, lord,’ and ‘It was a bear, lord,’ were the most that could be got from him, but gradually he told more and more of the story. His dialect was difficult to follow, for speech differs from village to village in Garhwal; but Mr. Bennett had been ten years in the hills, and he had applied himself seriously to the dialects when he first came. And Kalyanu himself gradually acquired a rather more sophisticated vocabulary. When his story had been fully explained, an impression was left of courage and initiative that was enhanced by his cheerfulness in pain and his obvious gratitude.

Mr. Bennett was not ambitious for an outwardly successful career ending in high office and many decorations, but he was by no means an ordinary man. He was a solitary, a poet, and a mountaineer. Had he been ambitious in the conventional sense, he would not have exerted himself in his early days to get on the Kumaon Commission, which could lead to no great post; had his recreations been those of most men, he would have preferred to his present loneliness the life of the plains, where there would be polo, pigsticking and racing, and brandy and soda at the club. But he loved the hills. He would perhaps never be the kind of mountaineer who writes books, or of whom books are written, but his love for mountains had guided his life. His long vacations in Oxford days had been spent in Switzerland, and it was to Switzerland he went on his first leave. He taught himself to climb in the Alps without a guide and he then began to experiment in the Himalayas, not with any object of making a name for himself or of achieving what had not been done before, but because the silence of the snows in high places raised his clear spirit to a wordless delight which nothing else could equal. As for poetry, every mountaineer is a poet at heart, though few have been poets in execution. Mr. Bennett might have been called a poet by virtue only of his pleasure in singing water, rock and cliff and flower and icy peak, but he was also a lover of the English poets, and of a most catholic taste. He read them all, and not the old masters only, for he had a standing order with his booksellers in Oxford for the latest works of his contemporaries. He might perhaps have been called uncritical, for he did not take sides in the controversies of his day, but found a stimulating pleasure in wrestling with Browning or Coventry Patmore and yet turned with an equal anticipation of happiness to the smooth melodies of Tennyson and Matthew Arnold. But this argued wide interests, not lack of standards; for he burnt his own efforts remorselessly.

Mr. Bennett did a good deal of reading in his lonely evenings in camp but he was conscientious in allowing himself only a limited amount of time for his other recreation of mountaineering. His duties as Deputy Commissioner of Garhwal need not have been exacting, for although he was judge, policeman and chief executive officer in one, the admhistration could really have been suspended for a few months without anyone noticing much difference. Crimes against property were unknown, murder and assault were rare. There were so few Muslims that communal trouble was not even thought of. The only local official of whom the villager had any knowledge was the patwari, who with the help of one servant collected the land revenue—almost a token rent—and admhistered criminal justice for some sixty to a hundred villages, with no sanction but the authority of the Government and the possession of a shotgun. There was not even much scope to the patwari for rapacity, for every villager paid him annually a gift of grain which was a fixed proportion of his crop. Although this amounted to ten times the trivial wages paid him by government, neither the patwari nor anyone else regarded the practice as dishonest, as indeed it was not, for, since everyone paid regularly, he was on the whole as fair as his intellect and training permitted him to be.

For Mr. Bennett, therefore, the constant effort to prevent extortion which in those days made up most of the life of his colleagues in the plains hardly existed. His checks of the work of minor officials were little more than a formality. He could have spent his winters shooting tigers where the hills break down into the plains, his spring and autumn fishing, and his summer mountaineering, without anyone being actively the worse. Indeed, this was just what some of his predecessors had done. But he was a man with an essential goodness of heart who believed with no shadow of doubt that he was where he was for the good of the people he ruled. He made no attempt to change their way of life beyond putting an end so far as he could to certain practices which were repugnant to Christian morality and which orthodox Hinduism would have disowned. But he did think deeply about the welfare and the admhistration of his people and he came to the conclusion that, since most of the troubles which came to him were disputes about the ownership of land, the most beneficent boon that good government could bestow would be maps of the fields and a record of every man’s rights.

After some months of correspondence he managed to convince his government that this was so and a survey expert was sent to make experimental maps. The expert made an accurate trigonometrical survey of one village and took two months to do it. His maps showed every terrace and every field. But he calculated that to cover the whole district would absorb four times the annual revenue received from the district for ten years. Government shook its heavy head.

So Mr. Bennett invented an ingenious form of survey of his own, which could be carried out with no equipment but a few ropes for measuring distances and which concerned itself with no trigonometrical pedantry. By this means he could make sketch-maps that would serve his purpose in one-eighth of the time taken by the expert and at one-thirtieth of the cost. And to this, after more months of correspondence, his government did agree; and so Mr. Bennett camped in every village of the district, worked ten hours a day to make his maps, and was happy.

When Kalyanu was well enough to walk, he felt no desire to go back to Bantok. Life there would not be the same without Autaru, and they seemed to be getting on fairly well without him, for Amru had developed unsuspected powers of leadership. Also, Kalyanu had tasted something of a more varied and on the whole rather less arduous fife. But behind these superficial reasons was a warm positive desire to be near the man who had saved his life, and for whom he felt a real devotion and affection. He could not formulate these wishes to himself, much less tell them to anyone else. He hung about the camp, trying to bring himself to go to the District Sahib and ask to be allowed to serve him; but he was too shy to come to the point.

He was brought to the point, however, by external circumstance. And this happened at the one moment most opportune for himself. Had it happened on any other day, Mr. Bennett would have told him he had no place vacant and advised him to go back to Bantok; and Kalyanu and his son and grandson would have lived out their lives in the yearly struggle to harvest enough grain to feed the homestead for another year. But the chances of this one day were to lead to the uprooting of himself and his family from Bantok and to the complex revenge which his grandson Jodh Singh was to take on society for uprooting him.

There were three threads of chance that twisted together into a pattern and altered Kalyanu’s life. The first was that Mr. Bennett changed the plans for his march without warning, a thing he did from time to time to make sure that he saw what was normal and not something specially prepared for the occasion; the second was that having varied his plan he made a further variation within it because he was a mountaineer and felt he deserved a holiday; and the third was that Keshar Singh, one of his orderlies, had a friend in the village of Marora.

Mr. Bennett was moving eastwards along the south side of a steep ridge which varied between nine and ten thousand feet in height. There was a well-established route along the south side about three thousand feet below the crest of the ridge, with regular halting-places. If you went three days’ march along it, everyone assumed you would take the next step and go on to the fourth halt. It was for this very reason that Mr. Bennett decided that he would leave it and go over the ridge to look at some map-making which was going on among the lower villages on the north side of the ridge. The locals shook their heads when he told them he was going to cross the ridge.

‘There is no path suitable for your Honour,’ they said.

‘But there is a way?’ persisted Mr. Bennett.

‘There is a way that goats and shepherds take,’ they admitted, ‘but it is not a suitable path and there will be snow.’

Mr. Bennett pointed out that there was not much snow yet, only a sprinkling, and that where a shepherd could go, so could he. He gave orders that next morning his camp should cross the ridge by the goat-path.

They had packed the first loads and the first porters were moving off when he started next morning. He came out of his tent and stamped his feet and clapped his hands for warmth in the diamond sunshine. The breaths of men and mules came in puffs of steam. There was still frost in the shadows of the bushes and behind the tent. To the south, the hillside was cultivated right down to the stream; every arm and root running downwards and outwards was wrinkled by the terraced fields like the skin of some very ancient and scaly beast. Looking down on them from above they were as regular and orderly as the rings in the stump of a great tree, or the scales on a butterfly’s wing. They were ploughed and sown for the winter crops.

Mr. Bennett turned and looked up to the north. From about the level of his camp to the crest, there was thick forest, from which, here and there along the ridge, peaks of rock or grass-clad domes stood out, sprinkled with the first powdering of snow. There was no wind and the smoke from the village to the east hung in a blue mist over the pines and oak scrub, sparkling with refracted light. A frosty, sparkling, diamond morning, thought Mr. Bennett, and his spirit rejoiced at the thought that he would see the snows of the main range when he reached the crest.

His three orderlies approached, Amar Singh, the senior, with his square competent face serious, his black pillbox hat tilted over one eye as he had pushed it when considering some problem about the loading of a tent; Keshar Singh, humorous, his crinkled brown face waiting to widen to a grin at the first excuse; Bharat Singh like a small boy unexpectedly grown up, with his ears standing straight out from his head, and his terrier air of wanting to be taken for a walk. No one had ever got more than ‘Yes, lord’ and ‘No, lord’ out of Bharat Singh, Mr. Bennett reflected. He smiled at them all with affection.

‘Who is coming with me to-day?’ he asked.

‘Keshar Singh, lord,’ replied Amar Singh. ‘Bharat Singh is going on ahead as quickly as he can, and I shall see the last loads off and come with the coolies to see they do not rest too much.’

Mr. Bennett nodded and turned to go. The path at first, was not difficult, for it was the way to one of the main village grazing grounds and led on to another village. It ran through patches of pine forest, where the reddish boles of the long-leaved pine stood up like the straight limbs of prehistoric animals, coated in plates of scaly bark, and the sun lighted the brown floor of needles; then through patches of evergreen oak scrub and rhododendron; and then began to climb, the long-leaved pine giving way to the blue pine and a few deciduous trees appearing. In one glade, Mr. Bennett stopped for a moment entranced. Through a tangle of rusty bracken and patches of bright couch-grass ran a little brown stream, tinkling happily over a dozen tiny falls. Alone in the glade stood one chestnut-tree, naked against the wintry blue of the sky, in a pool of its ruddy fan-shaped leaves. There was an autumn smell of dying leaves and frost and moisture. It was home, the English autumn, the English woodland. Mr. Bennett shook his head and went on.

Keshar Singh had enlisted a local man to show the way, whom he now led forward to introduce. He pointed out with his usual crinkly grin that here they must leave the main path and begin to climb. It was not easy going, overgrown with trees and scrub and extremely steep. All three men had to use their hands to pull themselves up and there was no more walking. After about two hours of this, they were on the saddle. The ground was comparatively level for a few yards and then began to descend. The path, if it could be called a path, for it needed some skill to see where it ran, led straight on, and by that road the porters and the camp would go. But Mr. Bennett wanted to see about him and on the saddle he was still among trees which obscured his view. He had noticed before starting that to the west of the saddle there was a sharply pointed peak, which seemed to be about ten thousand feet or rather more, with a rock face which might have possibilities; and he felt he owed himself some recreation, for there were no Sundays in camp. So he turned sharply westward.

In another hour he was out of the trees and only a few hundred feet below the little peak. It would be possible to walk to the summit if one kept on the north side but Mr. Bennett wanted some exercise on rock to keep him from getting rusty. He sent Keshar Singh and the local man by the easy route and himself spent a happy half-hour clinging by toes and fingers to the rocky southern face. There was a refinement of pleasure in this, because as he climbed he could not see the snows of the main range. He saved them up, like a child with sweets, until they burst upon him when he reached the summit. There they were, icy dome and snowy cliff, fluted ridge and needle, blue and white and silver, clear and hard in the diamond air, calm in the gay sunshine. Mr. Bennett held his breath in wonder and happiness, as he had done the first time he saw them, as he would do the last. Keshar Singh and the local man also sat and gazed.

After eating some sandwiches, Mr. Bennett began to discuss the way down. Keshar Singh and the local man wanted to go back to the saddle as they had come and follow the goat-track. It was the obvious route and Keshar Singh was particularly anxious to get into camp early because he had a friend in Marora village, an old comrade who had served with him in the 3rd Gurkha Rifles.2 But Mr. Bennett disliked doing the obvious, partly from temperament and partly because if he went by the obvious route everyone he met was expecting him. He favoured following a spur which ran due northward and reckoned that once they got down from that spur to the level of their camp they would find a lateral path that would take them the right way. Keshar Singh argued that the spur would end in precipice and the local man backed him, but had to admit he had never been on it and did not know the villages below it. Mr. Bennett was not to be persuaded and they started along the spur.

It was fairly easy going at first, through open country rather like a Westmorland fell, except for the forest immediately below them on all sides. But where the spur broke its smooth line, at the first knobbly knee, Keshar Singh and the local man both registered expressions which plainly said: ‘I told you so.’ For ahead to the north was sheer rocky cliff, and to the east, the side to which they wanted to turn, was a grassy slope on which none of the three would have trusted themselves. The only way down was to the west, and this they took.

The slope of the ground brought them into a side glen with cultivation among the trees. There was the smoke of a village up the glen to their left. They found a path leading downwards and out of the glen to the north and hurried along it, hoping for a more frequented path that would take them eastwards. Their path was little used and they met no one till they turned a corner and saw a small figure weeping in an utter abandonment of grief, one arm raised to lean against a boulder the size of a cottage, her forehead bowed on that raised arm, her whole body shaking with her sobs. She wore the uncomely blanket dress of the hills, which conceals the figure, and of her head nothing could be seen but matted dark hair, bleached here and there to auburn.

Mr. Bennett approached her gently. It would be very difficult to find out what her trouble was. If Amar Singh had been with him, he would have deputed him to find out, but Keshar Singh, who was kept on as an orderly mainly for his humorous expression, was unreliable. He was in a hurry, and if he were left to find out the truth, he would put words into her mouth and report them as though her sobs had confirmed them. Mr. Bennett must talk to her himself and try not to frighten her. He sat down on the ground, not too close, not too far away.

‘What is the matter, daughter?’ he asked.

There was no answer, and he repeated the question gently.

‘She is only a Dom, lord,’ said Keshar Singh. Mr. Bennett told him to be quiet, and repeated his question.

‘My master,’ she sobbed. She meant her husband, and Mr. Bennett felt it was going to be more difficult than ever. But for once Keshar Singh was helpful.

‘He has been beating her,’ he said with a grin, in a voice which might just pass as an aside to the local man.

‘No, no,’ sobbed the girl, raising her head and showing a smooth round chin and a snub nose that would have been attractive in a face less disfigured by tears. She was young, almost a child. ‘They are going to kill him.’

‘Why are they going to kill him?’ Mr. Bennett asked gently.

‘The rope festival,’ she wept, her head falling again on her raised arm.

‘When will it be?’ Mr. Bennett asked still more gently. He was very near something important, and he silenced Keshar Singh with his hand.

‘To-morrow, in the afternoon.’

‘And where? Here in this village?’

Between her sobs came a just distinguishable yes.

Mr. Bennett rose to his feet.

‘Do not tell anyone you have seen us,’ he said. Do you understand? If you tell no one at all, I will save your husband. Do you understand?’

She was lost in her sorrow and did not answer. Nothing would save her man. But Mr. Bennett judged she would not be likely to talk, while if he took her with him, the cat would be out of the bag and things might later be unpleasant for her. He left her and pressed on. It was after dark when they found the camp.

The girl by the rock stayed on. She was hardly conscious that they had been there; if she had been asked she could only have said that she had spoken to strangers, without knowing who they were, for there was no room in her heart for anything but her grief. At any other time, she would have been tongue-tied in the presence even of men from another village, but her defences were down, she reacted without resistance. She had given them the one thought in her mind—‘My master’—and then Keshar Singh’s lucky brutality had stung her to protest. For her husband was kind to her. He did not beat her and she loved him dearly.

She stayed there by the rock with her grief till she suddenly realized that she was cold and it was getting dark. She had come out to get sticks and had only collected a few when her sorrow suddenly became more than she could bear. She dabbed at her eyes with her blanket skirt, pushed back her hair, blew her nose with her fingers, picked up her sticks and started for home.

Her husband was in the house and had begun to cook the cakes of millet flour.

‘You are late, Padmini,’ he said.

She did not answer, but turning her face away from him, put a pot of porridge on the side of the fire and squatting down beside him, took over the patting and tossing and roasting of the coarse pancakes.

Sohan Das himself was less disturbed than might have been expected by the thought of the ordeal he had to face to-morrow. It was not true that the villagers had decided to kill him. What they had decided was to hold the rope festival. This had been forbidden by the British Government but they felt sure that no one would come to hear of it. Theirs was a lonely and isolated glen, which the patwari did not often visit. He had been there recently and now he was busy in the villages down by the river where the maps were being made. He would not be in their village again for a month at least. So it would be safe to hold the festival, which was exciting to watch and fun for everyone but the victim, and was besides a sure way of making the fields fertile. Everyone knew that the fields used to be more fertile when the festival was held every year; nobody remembered that there were then fewer people and more land and the fields were left to lie fallow occasionally. So the villagers decided to hold the feast and the young men were sent up to the top of the cliff above the village from which the victim began his descent. They looked at the tree to which the rope had always been tied. It was still quite firm and strong; they fixed a post in the fields below and began to make the rope, two hundred and fifty yards long, and the wooden saddle on which the victim would sit.

It was a form of human sacrifice which combined the pleasures of a simple exercise in geometry with a sporting gamble, a free-for-all rough-and-tumble in which nothing was barred, and a lucky dip. The top of the precipice was about five hundred feet above the level of the fields and the post to which the lower end of the rope was fastened was about the same distance from the foot of the precipice; the rope when tied at both ends therefore made an angle of about forty-five degrees. The victim sat on a piece of wood shaped like an inverted Y, the inner angle of the fork being polished till it was smooth and slippery. He held the upright in his hands and put his legs over the branches of the fork. Stones were tied to his feet and to the lower forks of the saddle so that it should not overturn. There was a simple ritual; his forehead was marked with a splash of colour in which a few grains of rice were stuck. Then he was released. He would shoot down the curving rope with growing speed, and one of three things would happen. The rope might break, which happened seldom; it might catch fire, which happened frequently; or he might reach the lower end with nothing more than a few bruises or a broken leg, which happened less often. If the victim fell, the crowd at the lower end of the rope raced for his body, each man eager to pluck a fragment of his hair or beard, even his clothes, to bury in the fields and bring fertility. If the victim reached the ground alive, there was no race, but there was an added zest in the struggle for fragments of his hair or clothes, partly because there was less that was detachable and partly because the detaching was painful to the victim.

The prospect of being the victim was not one which would have much general appeal, but to Sohan Das it did not seem more unusual or alarming than the birth of her first child seems to a peasant woman. His community, a sub-caste among the aboriginal Doms, had always provided the victim for this festival and they were rewarded at the time of the festival by gifts of grain from all the shareholders in the village. It had hit them hard when the festival had been forbidden and they had been the most eager that it should be held again. They chose the victim on each occasion by lot, but a survivor, like the member of a jury, was exempt from service until there was no one else available. Sohan Das regarded the whole business as part of the course of nature, something which ought to happen and which must happen to him sooner or later. The fact that the festival had not taken place in the last few years seemed to him something impious, an interference with the seasons and the ways of God.

But it was different for Padmini. She was younger, and she came from another village where the festival had stopped earlier. She had only seen it once. She had seen the rope smoke and break into flame; she had seen her father falling, slowly, slowly, it seemed for a protracted second of time, his hands clutching at the air above his head; she could remember the distorted angles of his limbs when the villagers had left him and she followed her mother to what remained. To her, the warm kindly man with whom she shared her life was already broken, stripped and lifeless. She lay down in sorrow and her young face was wet with tears when she fell asleep.

Mr. Bennett, on the other hand, lay down to sleep with a pleasurable anticipation of excitement next day. His only fear was that Keshar Singh or the local man who had been with him might give away the fact that it had been the girl who had told him the secret. The local man, however, lived on the other side of the ridge and he would send him back first thing in the morning. Keshar Singh was more of a problem; either of the other orderlies could be trusted to keep their mouths shut if they were told, but not Keshar Singh. Mr. Bennett wondered whether he should send him back to headquarters and get another man in his place, as he had often wondered before, only to forgive him for his impudence and grin. He fell asleep without making up his mind.

It was next morning that the affairs of Padmini and Sohan Das impinged on those of Kalyanu. The latter shared a tent with the three orderlies, and it was a small tent in which the presence of an extra man was an inconvenience. Nobody minded much as a rule, but on the morning when the rope festival was to be held Keshar Singh had a hangover. As soon as he had been dismissed the night before, he had slipped away to see his friend in Marora and they had sat up over a bottle of spirits till far into the night. He woke up in a bad temper and grumbled at Kalyanu because he was in the way.

‘Why does this son of a bitch live in the tent with us? he said. ‘Who asked him to stay on in this camp for ever?’

‘I have a petition to the District Sahib,’ said Kalyanu, on the defensive, for the same point had been on his conscience for some time.

‘Then why don’t you give him your petition and go?’ Keshar Singh spoke with ill-humour because that was how he felt about everything this morning, but there was confirmation for his point of view in the silence of the other two. Kalyanu saw that he must bring the matter to the touch at once.

The orderlies knew that camp was not to be moved that day, and on a halting day no specific duties were assigned to the man who had gone with Mr. Bennett on the day before. Keshar Singh was therefore justified in assuming that he would have nothing to do that day. Ordinarily, he would have asked Mr. Bennett before he went to see his friend. But to-day he was afraid that if he showed himself the traces of his carousal would be evident; besides, he was very anxious to get back for the opening of the second bottle, which he thought might make him feel better, and he did not want to risk being stopped. He took a chance and slipped away.

Mr. Bennett meanwhile was just ready to start. He calculated that the sooner he got to the village in the glen the better. The girl by the rock had said the afternoon; he would get there by noon, which was as soon as he could without arousing interest by a specially early start, for it was between three and four hours’ march. By that time the situation should not have developed to a stage at which it would be difficult to stop. If he arrived when the victim was decked and on the altar, so to speak, things would be more likely to be awkward. He did not anticipate any difficulty, but it would be as well to take the patwari and two orderlies, instead of the one who usually came with him. It was Bharat Singh’s day, and Bharat Singh presented himself. The patwari was also standing by.

‘I want another orderly,’ said Mr. Bennett. ‘Whose day is it to look after the camp?’

‘Amar Singh’s, lord.’

‘Then call Keshar Singh.’

Bharat Singh looked exactly like a small boy asked to sneak on a pal.

‘He is not here, lord,’ he said.

‘Where is he?’

‘He has gone to the village, lord.’