Call the Next Witness

(Philip Mason)

To

E. A. M.

‘Call the next witness’, said the King. And he added in an undertone to the Queen, ‘Really, my dear, you must cross-examine the next witness. It quite makes my forehead ache!’

The People in the Story

- Pyárí, or Pyáran, the Flame of the Forest

- Gopál Singh, her husband

- Kalyán Singh, Gopál’s father

- Nannhe Singh, a leader of the Congress party

- Hukm Singh, a leader of the supporters of Government

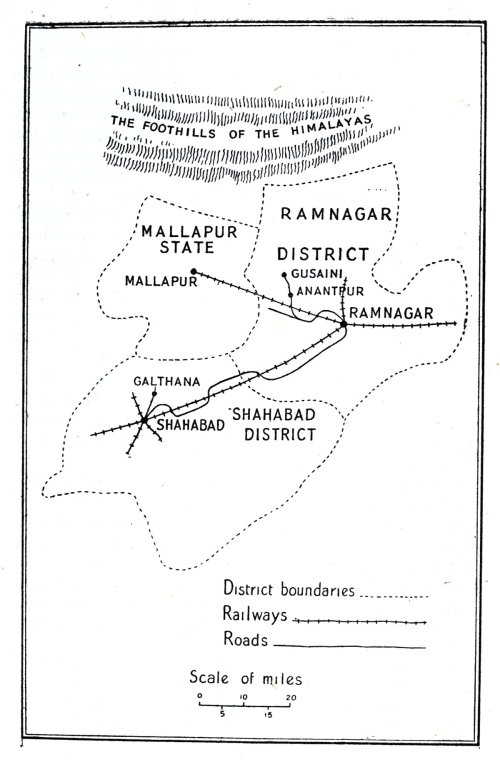

All these four are landholders of Anantpúr in Rámnagar District.

The following come from Galthána in Sháhábád District:

- Sáhib Singh, Pyáran’s father

- The Thákuráni, Pyáran’s mother

- Bitiya, Pyáran’s sister

- Bhola Náth Singh, Bitiya’s husband

- Rám Kallán Singh, a servant of Sáhib Singh

- Jeháran, a Bráhmani, Pyárí’s old nurse. The First Witness

- Rúp Singh, Constable, of Gosaini police station, near Anantpúr

- Sheo Dat Parshád, a Bráhman of Anantpúr

- Prem Ráj, a servant of Kalyán Singh

- Ghulám Husain, Sub-Inspector, of Gosaini

- Mohammad ‘Isháq, Inspector of Police, of the circle containing Gosaini

- Salámatullah, Sub-Inspector of Police in Rámnagar city, Mohammad ‘Isháq’s nephew

- Christopher Tregard, District Magistrate of Rámnagar

- Khán Bahádur Mohammad Altáf Khán, a leader of the followers of Government in the neighbourhood of Anantpúr and Gosaini

- Phúlmati, a bania’s wife

- Mathura Dás, her husband, a bania, of Purán Kalán, near Anantpúr

- Jhammu Nat, a gypsy engaged in an intrigue with Phúlmati. The Second Witness against Gopál

- Chabbli Parshád, a hillman, said to have sold pease to Jeháran. The Third Witness

- Hanuman Singh, a hanger-on of the Anantpúr family

- Prem Badri Náth, a Bráhman of Sháhábád, said to have bought Jeháran’s ticket. The Fourth Witness

- Dost Mohammad, a bus driver of Sháhábád, said to have taken Jeháran to Galtháná. The Fifth Witness

- Ahmadi Ján, his wife

- Babban Sáhib, Ahmadi Ján’s former employer

Introduction

This story was written in 1935, and for various reasons put away and forgotten until now. A picture of village life in Northern India in the time between the two wars may seem strange reading in 1944, but India is one of the problems to be faced after the war, and there are people both in England and America who are concerned that the political revolution which is being carried out in India shall be a success. Some of them may be interested in the private affairs of Indians and in the methods of local administration.

The tale could not be told in the familiar shape of the detective story because the police in India are faced with quite a different problem from the police of fiction. It does not usually take long to find out who their man is, but their work lies in getting proof and in getting their witnesses to court. In this case, the private affairs of each witness and the pressure brought to bear on him decide whether or not he will give evidence; and so the personal story of each witness has to be told as a story within the main story.

Almost every incident is similar in skeleton to one that has actually happened, but the flesh and skin, the characters of the people concerned and their reasoning and motives, are wholly imaginary. They must be, because only the skeleton of a story can be known by a foreigner.

I have tried as far as possible to avoid Indian words, but names are inevitable and are confusing to a reader unused to India. For the pronunciation, it is enough to say that the vowels are pronounced as in Italian, except the short a which has the sound of u in the English word butter. For the first few times that a name occurs, I have marked the long vowels with an acute accent. Thus Pyárí is Pyahree, Rámnagar is Rahmnugger, and Anantpúr is Unnuntpoor. But as the word becomes familiar, I omit accents which are tiresome to English eyes. [Accents retained in this version.]

Since the story is fairly complicated, it will be of help to consult frequently the list of people at the beginning of the book, and to bear in mind the chapter headings. There is a list of the principal events with their timings at the end of the book.

Part One

Flame of the Forest

Her Marriage and Death

On the last day of her life, Pyárí sat at her spinning in the veranda before her bedroom. The house was a large one, straggling out in lopsided additions and annexes that had been built on at one time or another by ancestors, and her room was on the first floor, a kind of summer-house set by an afterthought on the roof of an older and larger building. The room itself was very small. There was just sufficient space for the two wide string cots where she and her husband slept, for a few tin trunks piled on top of each other, and for the oddments of gear lying untidily here and there --- her husband’s English gun and a box of cartridges, an old red skirt that must have belonged to one of the servants and which no one had moved for months, a brass pot, and a photograph of some young men at Agra University. To English ideas the room would have been small for a bathroom.

In front was the veranda where Pyári now sat spinning. It was really another room, with three arches instead of a wall on one side. The arches had been shaped very crudely into the escalloped flounces which the Moghuls loved, and tho’ it was light here compared with the bedroom, anyone outside on the roof would have seemed to himself to be peering into a dark cave. In front of the veranda was a stretch of roof, as big perhaps as the room and the veranda together, fenced with a low wall against which stood some old kerosene tins cut in half and filled with earth; a few herbs and spices were growing in the this and some weedy marigolds. Out there, the sun was a bright intensity.

If you stood on the space before the veranda you saw below you a tumbled huddle of flat roofs and sloped thatch, the mud huts of the labourers gathered together in the skinners’ quarter, the sweepers’ quarter, the potters’ quarter, rising thro’ the sunbaked brick of the better class of small cultivator, and a few new red houses of fire-baked brick built by shopkeepers, to the group of large houses at the top of the ridge where for generations had lived the little group of connected Rájput families who owned most of the land in the neighbourhood. Thákurs they were called, the old title of the head of the Rájput family, the caste of kings and warriors and feudal nobles. It was a long time since any of the Anantpúr Thákurs had done much fighting, but they were still given the respect due to rulers and soldiers. They were still the chief landowners and their houses still dominated the village.

Beyond the huddled roofs the level plain stretched for seventy miles. There were little squares of wheat and barley in the vivid blue-green of their first youth, squares of brown earth where the autumn crops had stood, sugar cane in its close-packed cluster of lances, and here and there bright fields of mustard rejoicing in the sun. Islands rose from the variegated cultivation, dark glossy groves of mangoes, and villages standing up on mud-coloured beaches; but there was no rise in the ground until the details of the plain were lost in the blue mist of the foothills, from which soared suddenly the high snows whose gleaming summits seemed to hang in the air, a vision at once gracious and majestic. The blue from which they rose was only a darker shade of the blue they pierced with airy pinnacles, that were as delicate as breath on frosted glass, but as hard as diamond.

But in spite of the wide expanse before him, anyone who had stood on the roof in front of Pyárí’s room would have been in a world of his own. The village had probably been built originally on a slight natural rise in the plain, perhaps where the changing course of some primeval river had piled the debris of its spate, and the continued activity of man, building his foundations on the ruins of his parents, had in successive generations inevitably raised the level of the site by a few feet, as a coral insect raises a reef. Thus the village stood out above the plain, and this house stood at the highest point of the village, perhaps as much as thirty feet above the level of the cultivated fields; and it was one of the very few houses with two storeys. The roof was a kind of eyrie, too high for observation from below, and this was one reason why Pyárí loved it. She liked to stand there above the village, whether in the early morning when only the tops of the mango groves showed above the white mist, in the limpid clarity of the first sunlight, or in the evening when the blue smoke was smoothed in level lines against the orchards, or now, at midday, when the village was hushed in the blinding light, and the few that were not in the fields sat indoors, spinning or sewing or cooking or grinding the corn.

But to-day the roof did not seem to Pyárí so pleasant a place as usual, for as her fingers followed the distaff her thoughts dwelt on her husband, and on all he had failed to be. She had always known the kind of husband she would like. Even as a child she had never had any doubt about what she wanted, and she had never hesitated to declare her wants. She was like her mother in that: a masterful woman, the old Thákuráni! No one who had not known her would have believed that a woman who hardly ever left her house and never showed her face to strangers could have dominated a community as completely as she dominated the village of Galthána, where Pyárí was born. Sáhib Singh, her father, had always been her mother’s slave. He was the chief landowner in the place, not, as here in Anantpúr her husband was, one of a group each of whom owned parts of a dozen villages, but sole owner of the village in which he lived. His grandfather would have thought Pyárí was making rather a poor match, but lately they had had to sell some of the land outside Galthána, while the Anantpúr Thákurs had been buying. But in spite of his sales, Sáhib Singh was still supreme in Galthána, partly because he was the landlord, and partly because everyone liked him. He was a slow pottering old man, but kindly disposed and singularly free from ambition or the love of intrigue. By virtue of his lands he was chairman of the village pancháyat, the court which could try the smallest local offences, but he did not use the position for his own ends, and he had no desire whatever to be a member of the district board, or to change anyone else’s way of living. It was the Thákuráni who managed the estate and very largely the pancháyat as well.

Pyárí was like her mother, but her younger sister, Bitiya, took after their father. She had the same dwambling gait and confused way of speech, and she had none of Pyárí’s fierce beauty, like a Rájput queen in the old stories, a fit bride for Indra, the antelope, the fire-god. Bitiya was as slow in her thoughts as in her speech, and she had always followed Pyárí’s lead so naturally that the elder sister fell into an easy and unconscious habit of despising her and leaving her out of account. But Bitiya was conscious of this if Pyárí was not, and, one day, long after Pyárí had forgotten some hasty saying she had never intended as a slight, but which had filled her little sister with bitter resentment, Bitiya said from her deep brooding: ‘You deserve to have a husband as ugly as a water buffalo!’ She pictured him to herself, the dark hairy skin, the heavy moustache, curling up like the buffalo’s horns, the sullen mouth and stupid eye. She laughed aloud. Pyárí stared at her in amazement. ‘Yes, and as cruel as Ráwan’, went on Bitiya, thinking how the demon king who carried away Ráma’s bride would have tamed her fiery sister till her beauty was spoiled with crying. She laughed again.

‘You little stupid’, said Pyárí, too much amused to be annoyed. ‘Of course, I shall have a husband as handsome as Krishna, and he’ll always be kind. It’s you that’ll get the ugly husband, ’cause you’re so ugly yourself’

Bitiya began to cry, and Pyárí at once ran to comfort her; which she soon succeeded in doing, for they were fond of each other at intervals, in a sisterly way. But afterwards Pyárí found it necessary to tell people, what she had always before imagined they must know, that her husband would be as handsome as Krishna, the god of youth and love and laughter and music, whose pipes brought with them beauty, like the breath of Dionysus. She used to dream of him, sometimes clear and pale of skin, sometimes flushed with youth and passion, with the proud Rájput features, the nose straight and the nostril delicately arched, the brow low and broad, with the full lips of the Greek, tall and straight of limb, swift of body and mind and scornful as herself of all who could not follow. That had been her dream, and she had never doubted that it would come true until it did.

The house at Galthána was a much less piecemeal affair than that at Anantpúr. It had all been built at one time to one plan. It was built of old bricks mellowed to a pleasant warmth; they were very small and flat, which gave the building a queer air of detail and intimacy. It looked as though much work had been spent on it and many lives lived inside it. It stood about a big central yard, and the high walls were blank on the outer sides.

You entered from the village street by a gate big enough to take a fully loaded cart, through a kind of tunnel in the house itself, to the yard, which was generally in some disorder. There were always pigeons cooing and fluttering about the roofs, and a rich smell of sugar filled the air. The cane was pressed in the fields where it was cut, but the molasses was brought to the house before being sent into Sháhábád, the nearest big town. There was usually a cart and a yoke of oxen standing there.

Her childhood at Galthána had been a happy one. All had been happiness and trust. Her father was a good landlord of the old-fashioned kind, who looked after his tenants in their troubles, sickness or lawsuits or failures of crop, and for whom in return they felt an affectionate respect. Perhaps because there was no son, but also because Pyáran shared the old Thákuráni’s adventurous spirit, she was treated when she was small much more as a boy is usually treated, and was allowed a freedom rare for girl children. She loved to go with her father, and he loved to have her with him, so go she did.

She even went with him on shooting expeditions, not long ones, for Sáhib Singh had neither the keenness nor the bodily vigour for a really tiring day, but excursions all the more pleasant to her for that. They went after quail in the cool of early morning in the spring-time, when the light was clear and gentle, in the tight land near the river. The men walked up to their knees in the low crops of wheat and peas, mixed in one field in an inextricable tangle, starred with the white flowers of the peas, still fresh with dew, until the sun rose higher, the dew dried, and the light hardened, and they would turn into a sandy track between the fields, and make for home, everyone talking at the same time about what he had shot. They went after snipe at midday in the winter, when the air was dry and invigorating and the sun a pleasant warmth, Sáhib Singh and his friends wading in the shallow mud and water, while Pyáran followed on the bank of the bog, watching the black and white magpie kingfisher hovering and fishing, and the long-legged water-fowl rising at each shot, crying and turning. Sometimes they went for longer days after hare and partridge, in the crops along the edge of cultivation, and in the sandy country by the river where nothing grew but clumps of tamarisk and little patches of coarse grass. They walked through the sea of crops or tamarisk, Pyáran following in a bullock-cart, the beaters whacking with their sticks at the tamarisk bushes, and shouting to put up the birds. When the sun was getting high, Sáhib Singh would call a halt and would find in the cart food for all the beaters, bread and curried vegetable and a lump of solid brown molasses. He would give it out with a word and a joke for everyone.

‘Here’s something for Loki; he needs a good meal, his wife had twins last month; a man as strong as he is must keep up his strength. Where’s Mannu got to? Always behindhand! Come along! . . .’ and so on.

But it was not only on shooting expeditions that Pyáran was allowed to go with the old man. Sometimes she would go with him to a neighbouring village where he had land, where he would sit and talk to the tenants and to the village record-keeper, and drink a glass of milk or sugar-cane juice with the village headman. Sometimes he would take her with him in the evening, when he went down to the fields to one of the many sugar-cane presses, to ask how the work was going on. The cane was brought in from the fields as it was cut, and there fed into a press worked by bullocks which squeezed out the juice. The juice was cooked on the spot, in flat iron pans, arranged over a mud-walled furnace. The pans were arranged like the steps in a staircase, the largest at the top, where the heat was less. As the juice cooked, a thick scum formed on top of it, and from time to time someone ladled this rich sugary scum into a smaller and hotter pan below, until in the smallest and hottest of all it was of the colour and consistency of hot caramel toffee. The furnace was fed by the dried pulp of the sugar-cane; and in the cold evenings of January the mouth of the furnace was a cheerful glow of light, always surrounded by a circle of cultivators and workers at the press who met at the one really warm place in the village. The warm, treacly smell of cooking sugar added to the feeling of companionship; and often when her father was not coming down Pyáran would slip away by herself and creep quietly up to the circle round the furnace-mouth, to listen to the slow bubble of the hookahs and the tales and the talk.

But usually it was in the central courtyard of the old house that Pyáran met the tenants. They used it as a camping-place if any business brought them into Galthána for the night---dealings with the police, the hospital, or with their landlord. They brought in their bullock-carts, lighted fires and cooked their meals, and their chatter was always there, as much a part of the place as the house itself. There was always work going on here too, for the solid molasses made in the fields at the little presses and furnaces was brought into the house and there refined into sugar by a simple centrifugal machine. Three influences pervaded the courtyard---the smell of sugar, the shrill voice of the Thákuráni Sáhiba scolding and commanding, and the physical presence of Rám Kallán Singh, the big Thákur who acted as watch-dog, sergeant-at-arms, and rent-collector.

Pyárí had been on one of the verandas of the court when her father had come in with a letter from the post office, a little further down the street, and told her that he had arranged her wedding. She was wildly excited and asked at once to see a photo of her bridegroom. The Thákuráni scolded her father for the way he had broken the news, but she was too pleased to be cross for long. Her plans had come about as she had meant, and she was almost as excited as her daughter, whom she took away at once to see a photo. There were two, neither of them very good. One showed him in a crowd of other young men, when he was at the University at Agra, and all she could tell was that he was tall, like the Krishna of her dream. The other, taken by a professional photographer, showed him grinning self-consciously in his best clothes. Pyárí studied them for hours, and decided that he could not possibly be like that.

It was not till she was married and had gone to his father’s house at Anantpúr that she came to know her husband Gopál Singh. At the very first, she had been a little disappointed; all the details of her Rájput hero were there, but there was something lacking in the total effect. There was the broad low brow, the arch of the nostril, the flashing white teeth, but there was a weakness in the round chin, a lack of fire in the eye and of pride in the carriage of his tall body that made her think he fell sadly short of Krishna. But it was a feeling that did not last long. He was the first lover she had known; except for her father and the servants and the labourers, he was the first man. He stirred her mind by talk of a world she had never even heard of, and soon he stirred her body too. He was a skilful and an ardent lover, and when in the first moments of delight she felt the smooth roundness of his arm and the supple muscles of his back, she believed that she had found the god of whom she had dreamed. She began to love him as she had always known she would love her Krishna, with an adoration near to devotion.

His education was imperfect, for he had no real taste for scholarship and had only been a short time at Agra, but it was sufficient to make him turn sometimes from the conventional images of oriental love poetry and seek for a comparison that he could invest with his own meaning. He had imagination, and one day when passion was spent, in a mood of tenderness for the lovely bride that fate had sent him, it struck him as inappropriate to compare this fierce bright beauty with the pale and fragile lotus blossom. He told her so, and sought in his mind for a flower more suitable. ‘Flame of the forest!’ he cried joyfully. ‘That is what you are like.’ Pyárí was delighted. She really was more like the flame of the forest than the lotus, and it was a flower she dearly loved. Neither scarlet nor orange, it is the true colour of flame, not the sullen glowing ember but the living, leaping tongue of fire, fit garment for the bride of Indra! She had always loved to go with her father to see the jungle in April, bright with these burning trees, laden with blossom without a leaf showing; and she had loved to take the flower in her hand, to feel its glowing velvet and admire the two butterfly wings and the rich tongue between. She was enchanted with this name for herself, and demanded a flame-coloured dress from Benares for her next present. Gopál saw that he had pleased her and he took to calling her Phuliya --- little flower ---in remembrance. He soon came to use the name to appease her when she was in one of her moods of temper --- and she flew into such tempers!

They had no honeymoon in the Western fashion, but went straight to Anantpúr, and it was there, living in her father-in-law’s house, that she first knew the delight of being loved and first fell in love with Gopál Singh. But if that happiness had not been there to sustain her, she would have hated the first months after her marriage. She had lived all her life in one house with her own family, and she was suddenly transplanted to a new world where all the values were changed. It was a rambling, untidy house, built like her own at Galthána about a central court, but without plan or order. There were odd little staircases running up outside to the roof or to little sets of rooms built on to the roof. All the roofs were of different levels. There were odd little rooms tucked away in comers, where you would suddenly find people whispering who broke off at your approach; what was worse, there were odd little doors going to other houses, the houses of distant cousins and uncles, and there was a continual coming and going by those doors of closed and secret lips.

At Anantpúr no one could have got a cart into the central court. So many additions had been built to the original house and so many new houses as the family budded and branched that you could not even approach the house except by tortuous passages between high brick walls. The court had grown smaller with successive improvements, until now it was dark because the sun only reached it at midday. The farming was done by tenants, or at little temporary houses in the fields where servants worked; and there was no honest smell of sugar and straw and cattle, and no murmurous cooing and rustling of pigeons. It was a house of whispers and intrigue.

Pyárí’s mother was a managing woman, and feared by all the neighbourhood, but she was affectionate and honest. She loved Pyárí, and if she scolded and flew into a temper, all was forgiven in half an hour. Now instead of her mother she had two mothers-in-law: Gopál Singh’s mother was dead, and Kalyán Singh had two later wives, both childless. One nagged and the other sulked. But a Hindu girl seldom expects much kindness from her mother-in-law, and Pyárí could have borne this if she had felt more at home in the house. She could never understand the continual family and political intrigue.

Kalyán Singh was nominally the head of the family group of Thákurs who lived at Anantpúr. There were perhaps a dozen families, cousins, second cousins and third cousins, and Kalyán not only represented the senior branch but was himself the oldest and wealthiest. But he had less influence than he should have had, because he stood for no fixed principle but the acquisition of money. He was not exactly a miser, but while he liked money and had got into the habit of hunting it, he had no direct interest in politics; and yet as things stood he was not strong enough to keep out of politics entirely. His cousin Nannhe Singh was gradually taking his place as leader of the clan, just because Nannhe Singh did take an interest in politics and knew exactly what he wanted.

Nannhe Singh was a hater. It was written in his face, which was neither a healthy brown nor the clear pale colour that sometimes yellow. It was a bitter face, but full of purpose, and the purpose was hatred. He had a sufficiency of enemies outside the family group, but they were not enough for him when ambition drove him to politics. He became a nationalist; he was bound to. It was the paying side in district politics, at least for a Hindu; it gave him something to hate; and it was based also on a genuine desire to see his country entirely in the hands of his countrymen. But although Nannhe Singh became a nationalist, he was no unconditional supporter of the Congress party, for the Congress party had uttered some ominous remarks about the tenure of land. He did not mind wearing cloth woven in India, because it was cheaper, and he was no Musulman to dress up in fine clothes; but he had no intention of giving up the rents he collected on hundreds of acres he never ploughed. So he was a nationalist, with reservations, and he became a member of the district board; and except for Kalyán Singh and one other, the Anantpúr Thákurs followed him.

While most of the landlords carefully made themselves friends with both the Government and the nationalists, and while Nannhe Singh’s little group of Thákurs were unreservedly for the nationalists, one man in Anantpúr was unreservedly for the Government. This was Hukm Singh, a second cousin of Nannhe and Kalyán. He had originally less landed property than the others, and since he was extravagant and a bad manager, his financial affairs became extremely involved, and indeed he continued from year to year with an expenditure larger than his income, by a process that was mysterious to everyone who knew him. He had not much to lose either way, and with a gambler’s instinct he had thrown himself into the part of the friend of Government. His enemies --- among whom he counted all his relations --- sneered that his visits to the District Magistrate and his attention to the Tehsildar and to the police were entirely obsequious time-serving; but it would have been equally true --- or untrue --- to say that Nannhe Singh’s nationalism was wholly selfish. Hukm Singh found that an Englishman usually received him with courtesy and with rather more than the respect due to his family. For several among the District Officers he had known he formed a real affection; so that behind his conviction that it would pay in the end to be the friend of power lay a vein of personal loyalty. It was pleasant to be chairman of the village pancháyat instead of Nannhe Singh or Kalyán Singh; it was pleasant to have a licence for a revolver and to enjoy the consequence its possession gave him, though he knew the District Magistrate did not really believe his story that Nannhe Singh would have him murdered in his bed without it; and it was pleasant to be allowed a little extra time in which to pay his Land Revenue; but these things were not really anything to do with his pleasure in talking to an Englishman, his pride when an Englishman came to his house, or his firm belief that chaos and anarchy would result if the English were not there to govern.

Kalyán Singh could not make up his mind to throw in his lot with either Hukm Singh or Nannhe. He had no ambition and he did not want to offend the District Magistrate; on the other hand, there was a good deal in what Nannhe Singh said, and he certainly could not afford to quarrel with all the rest of the Anantpúr group. So he went to visit the District Magistrate, but not very often; he voted for Nannhe Singh in the District Board election, and he subscribed as little as he decently could both to the King-Emperor’s Loyal Fund for Training Village Midwives, and to Mahatma Gandhi’s appeal for distilling salt (strictly against the law) from the sacred urine of the cow.

It was this indecision that Pyárí found so difficult to understand; she had no idea what either side meant, but, if she had had to take part at all, she would have been vehemently on one side or the other. Kalyán Singh himself she liked; only this bonelessness, as it seemed to her, filled her with irritation. She began to argue with her husband, but they could not understand each other, and she gave it up. A more serious trouble came between them over Jeháran, Pyárí’s old nurse, who had come with her to live at Anantpúr. Jeháran was a Bráhmaní, as one of the servants in a large house often is; for a Bráhman is the only Hindu who can cook food which every other Hindu can eat. She had been widowed before Pyárí was born, and she had no children of her own. All her life since had been given to looking after the two children, cooking and sewing for them, slapping, scolding and doctoring. A good deal of slapping and scolding there had been too, but the old Thákuráni never let her go. She knew that behind Jeháran’s bad temper was a genuine love, all the deeper because no one but the children had a place in it. For the rest of the world she had only bitterness and contempt; her master Sáhib Singh had her tolerance and her mistress her respect; but she loved Bitiya, and Pyárí she adored.

It was natural that when Pyárí was sent into this strange new world she should take her old nurse to live with her, at any rate until she found herself more at home. In the house of any well-to-do Indian, but particularly of the semi-feudal landowner, there are any number of hangers-on. Some are actually called servants, and are paid a nominal wage of a few shillings twice a year, besides receiving clothes and food. Others merely attend at mealtimes and depart from time to time on mysterious errands. Others will perhaps come for a meal once a week, or will stay for a few days at a time. Some are tenants come to pay rent, others are purely parasitic; but all owe a kind of shadowy allegiance to the head of the house, and they are understood to be his men in time of any emergency, whether an election, the coercion of a tenant, a big shooting party or a communal riot. Among these dependants, Jeháran was unpopular from the first. She had a sharp tongue, which she never hesitated to use, and she never lost a chance of expressing her contempt for Rámnagar district, Anantpúr and the household of Kalyán Singh.

‘Out of my way, first cousin of a flying-fox!’ she would say, expressing the relationship with an exactitude only possible in a language which has a word for every different kind of cousin, aunt or uncle. And if the victim was rash enough to answer, she would put her hands on her hips and set about him till he flew.

To Pyárí, however, she was a great comfort. They could talk for hours together, when Gopál Singh was away from home, of Galthána, the people there, and their superiority, for although Jeháran had never had a good word for man or beast about the place while she was there, now they seemed almost divine. And Jeháran at least was always ready to comfort Pyárí and understand her, after one of the mothers-in-law had been more than usually unkind. It was this that had led to the first big quarrel about Jeháran.

There had been from the start a certain amount of nagging.

‘There are too many people to be fed in this house!’

‘Useless mouths! And particularly when they belong to sulky bitches that do nothing but snarl and bite!’

And so on. But one day, over a difference that had nothing to do with Jeháran, Pyárí lost her temper. She felt it swelling up inside her till she must burst; red patches danced before her eyes; she could hardly breathe.

‘Dirty old monkeys!’ she suddenly screamed, ‘sitting here all day and biting and scratching! Too old and ugly to have children!’

Everything she could think of that would hurt she spat at them. The room was like a box of wild cats advertised by jays. All three screamed as loudly as they could. When they had finished all the abuse they could think of, they simply screamed without words. The elder mother-in-law slapped Pyárí’s face, and at that Pyárí ceased to be human: she was more than a match for the two together; she bit and scratched and tore until they were rescued by Kalyán and Gopál. Pyárí was taken upstairs and padlocked into her bedroom, still hysterical with rage.

But quite soon Jeháran found her way upstairs, and from outside it was quite easy to remove the padlock without a key.

For the moment, Pyárí was ready to kill either herself or her mothers-in-law. She had only to think of them for that dreadful feeling to swell again in her breast until she choked with fury. She really was ready to kill herself if it would make them sorry, and assert her own importance. If Gopál had come to see her while she was still in that mood of hysteria, and if he had spoken a word of blame or unkindness, she would have thrown herself from the roof.

But it was Jeháran who came and who agreed with everything she said and made her talk about Galthána, and at last suggested she should write home and ask to come back. Jeháran knew perfectly well that the old Thákuráni would be much too sensible to take any notice, but it would give Pyárí something to do at once and something to think about till an answer came.

Pyárí could not write much, but she could write all she wanted to say now: her little note was badly-spelt and dirty and crumpled and rather damp, but it left no doubt of what she wanted at the moment.

Jeháran slipped away with it to the post-box, where there was a collection every third day. But by the worst of luck, the Kahár who was the chief house-servant had felt the rough side of her tongue that morning, and he saw her come down from the roof. He followed her till she left the house; and he ran into the men’s sitting-room where Kalyán and Gopál were still wagging their heads over the unchanciness of women. Gopál was just in time to catch her at the post-box, but he had to run.

‘What’s that?’ he asked, out of breath.

‘A letter.’

‘Who to?’

‘It’s no business of yours. It’s my letter!’

‘You can’t write.’

‘Yes I can. I’ve just learnt.’

He snatched the letter from her and read it as he went back.

From that hour there was always war about Jeháran. The whole household except Pyárí united in saying that she was a spy and had no place at Anantpúr. But unless Pyárí agreed they could not send her back, because that would have meant a definite breach with old Thákur Sáhib Singh at Galthána. This they feared, because there were no sons and Sáhib Singh could dispose of the property between his two sons-in-law very much as he liked. They combined then in trying to force Pyárí herself to send Jeháran back.

In spite of the quarrel about Jeháran, Pyárí continued to be in love with her husband. But gradually she began to find him out. The first fault she found with him was physical laziness, a thing she hated and could not understand. She would have given all that was dearest to her to go about the fields as she had done when she was a child, but though Gopál enjoyed both riding and shooting when he went, he was never eager to go out, and for hours together he would sit idle, or he yawning on his bed. Then she would flare up at him like fire in the forest, and he would turn sulky until something she said hurt his pride, and he would lose his temper as quickly as she did; the same mastering passion would boil up in his veins, and she had to be very quick to avoid being hurt. For with him she had never blazed in fury as complete as she had known against the old women. She enjoyed taunting him, and she always contrived to keep near the door; by the time he had followed her downstairs his passion had disappeared in sulkiness.

His lack of character she realized more slowly than his laziness, but gradually she came to see that behind a superficial cleverness and imagination there was nothing solid except self-love. He was weak in quite a different way from her father, who was naturally kind-hearted and wanted to be friends with people, and who, being mentally slow, never realized he was being driven into a silly act till it was too late. And there were some things her father could never be made to do, because he would at once know them to be wrong or cruel. But Gopál was quick of mind; he would see at once where he was being taken, and along some roads you would never drive him, because his own interest and pleasure would suffer if he went. If he did anything silly, it was pure laziness that led him to it. And he was like a child with sweets; he could never say no to pleasure. His laziness was such that he had never controlled himself or directed his own life, but had been blown where his immediate wants had led him.

As Pyárí gradually saw through him, her love for him changed, but it continued. She no longer thought of him as Krishna; that was a childishness at which she smiled. But while of much of his character she thought fondly as a mother proudly recounts the naughtiness of her child, there was something in his utter selfishness and lack of moral standards that fascinated her and rather frightened her. He had, too, imagination and sudden spurts of originality, tempered by the laziness that prevented him from executing his ideas. And his body still held her; she never lost a little thrill of excitement at the sight of his tall figure; the turn of his head and his smile still seemed to her the comeliest in the world.

But though she loved him, Gopál could hardly be said to love Pyárí. His was a nature that could be swayed by desire or passion, and to a very limited extent by affection, but the two were never fused into love. He had accepted without objection his father’s decision that he should marry, since it never occurred to him to give up the amusements with which he had satisfied himself before. And he had been delighted when fate sent him a bride of such beauty. She pleased him so much that for a long time he was faithful to her, merely because he saw no prospect of an amusement more enticing. With the satisfaction of his desire, there grew in him a kind of affection, but it was little more than the affection of association, the kind of feeling a dog knows for the servant who brings his dinner. More than this it was difficult for him to feel, mainly because his nature was too shallow, but partly because he and Pyárí had not chosen each other, and no consideration of whether they had any thoughts or feelings in common had entered the choice. She found a love for him because of his good looks and because he was Ferdinand to her Miranda. He was all she knew. But he had known many others, and it was only her body that drew him.

They had been married nearly a year when something happened to change everything. As is the custom, she went home to her family to stay for a month, taking with her Jeháran: and Gopál Singh came to take her away. It was at first a friendly family party, with no hint of trouble. The Thákuráni had heard the story of Jeháran, and the quarrel about the letter, but she realized that there must always be some feeling between a daughter and mother-in-law, and particularly so when the mother-in-law is a childless second wife. She knew the difficulty of the first year of marriage added to the difficulty of absorption in a new family, and in her wisdom she decided to forget all she had been told. She was kind to Gopál, and showed him all she valued most, as an affectionate mother might be expected to do with a son-in-law of whom she thoroughly approved.

Bitiya was married now, but as she had married a younger son and Sáhib Singh was getting too old and too kindly to go round collecting rents, Bitiya and her husband Bhola Náth Singh had come to live with her parents in the house at Galthána. Bhola Náth collected the rents, and Bitiya was supposed to help her mother, but she was never allowed to do very much. Pyárí envied them this, but she did her best not to show it and told them how much better everything was managed at Anantpúr. But she told her mother the truth.

When Gopál came Bitiya remembered the water buffalo and began to giggle, which annoyed him and nearly earned Bitiya a slapping from her sister, who knew what she was thinking about. Gopál, however, was on his best behaviour and at such times he could be charming. On the second day of the visit he surprised everyone by suggesting quite casually that Sáhib Singh should come with him on a pilgrimage to Hardwár. Pyárí was more surprised than anyone, for she had heard nothing of this, and she knew better than anyone that Gopál Singh had no interest in paying his respects to Mother Ganges. She supposed, though, that he wanted an excuse for a journey and perhaps planned to meet some old companions at Hardwár, but she could not imagine why he should take Sáhib Singh.

The old man was delighted. He thought it would be a pleasant change and a holiday. He was proud that this handsome young son-in-law wanted him and at the same time he would be doing his duty and washing away his sins.

‘When shall we start?’ he asked excitedly, like a child.

‘As soon as you like’, Gopál told him.

Pyárí was pleased because it gave her longer at Galthána. They were to come back there after the pilgrimage and then Gopál would take her away. Two days later they got into a bus and drove to the headquarters of the district, the city of Sháhábád, to catch the train for Hardwár.

The station was crowded, as stations in India always are. This is because no one but an Englishman leaves till the last minute so important a matter as catching a train, and the ordinary person prefers to come two or three hours before the train is due. The trains are always quite full, and thus there is at least a trainload of people waiting on every platform.

Sáhib Singh looked at them with pleasure. He loved the adventure of a train journey as much as the simplest peasant did. Most of the people who sat there waiting were cultivators. The men wore clothes of heavy but very coarse white cotton cloth, of about the consistency of meal sacks. They wore a loin-cloth of finer cotton, a kind of shirt, a pair of unlaced slippers curving up like a canoe at the toe and the heel, a turban, and a large sheet which they wound over their shoulders, like a shepherd’s plaid, but as big as the sheet of a double bed. Most of them squatted on the ground, muffled to the eyes, but a few lay stretched on the platform sound asleep, wound from head to foot in their sheets so that they looked like corpses. A month earlier in the year, when it was really cold at night, every villager would have brought his quilt and would have sat muffled to the eyes in that.

The women wore gay colours. Of the peasants, the most part had a kind of bodice, or waistcoat buttoning down the front, and a very full skirt which made them a sufficient garment without underclothes. When it is spread out on the ground to dry, this skirt is so full that it makes a circle seven feet across, with a small hole in the middle, and even then the hem will not he flat. In movement it is beautiful, frothing like the crest of a wave above the ankle to reveal the curve of the heavy silver anklet and the bare foot. The favourite colour was a dark red with a broad black border at the bottom, but apple-green and canary-yellow shone there too, since everyone had put on her best to come to the city.

The richer women wore the sári, most graceful and becoming of garments, which winds round the whole body and over the head. All but the Musulman women wore as much jewellery as they could, heavy anklets and bracelets of debased silver, nose-pendants and necklets and long pendants from the ear. Musulman women of all but the lowest class moved like sheeted ghosts in the burqa, a kind of walking white tent, with a cowl for head-piece and netted eye-holes.

But the delight of the station lay in its variety. There were sweetmeat sellers whose wares looked as greasy and sordid as themselves, boys languidly trying to sell clay dolls or walking sticks, men raucously trying to sell nuts, or calling in a long wail: ‘Hot tea!’ ‘Ho-o-ot te-e-e-ea! Musulman te-e-e-ea!’; while a rival bawled as loudly: ‘Hindu te-e-e-ea!’ There was a band on its way to a wedding, the men worn out with having played continuously for three days and nights at their last engagement? They lay fast asleep on the platform, each man with his head pillowed on his precious instrument. Fakirs, their bare bodies smeared with ashes to disguise a chubbiness never seen among the villagers who fed them, eyed their next dupes with arrogance. There were coils of false hair on their heads, smears of paint on their faces, and their looks were lustful and beastly. Priests were there in long saffron robes telling their peach-stone rosaries, their shaven faces blind to this world; banias reckoning the day’s gains; a group of swaggering young soldiers on their way back from leave; three or four clerks talking English, and a Pathán moneylender by himself, his wild face framed in his long black locks, glistening with oil.

Scraps of conversation drift up:

‘Our pleader was a good one; he asked a great many questions. . . .’

‘I shall have a new pleader next time, the Deputy Sáhib was very angry with this one. . . .’

‘He is only a very ordinary man, a bania, and his father had a shop in the village. You cannot expect the Sáhib to be impressed with a man like that. . . .’

‘I gave the Court Reader twenty annas. Everyone knows that is what a Court Reader always takes, but he said it was not enough....’

‘They were asking nine pice for a brass pot only so big. . . .’

‘I know he will never pay me, but his land is mortgaged and he will have to sell me the land. It is good land and will take Coimbatore cane. I shall put in tenants and . . . ‘

And this in English, of which Sáhib Singh could not understand a word and Gopál only a little.

‘Yess, yess; if he pass, well and good; but until and unless he pass what for he put on airs?’

There was a gargantuan clanging and whistling; the rails gleamed in long silver lines; jewelled lights sparkled ruby-red and emerald-green.

Suddenly all was confusion; coolies rushed here and there among piles of luggage; hawkers redoubled their efforts; every bell in the station seemed to be ringing; far away the searchlight of the engine swung slowly round towards them, grew and grew and grew into intolerable intensity, while the thunder-muffled clank of its oncome swelled to a tremendous crescendo and died in a harsh grinding and hiss of escaping steam.

Sáhib Singh and Gopál climbed into their train and were borne swiftly away to Hardwár.

Hardwár stands where the Ganges breaks out from the hills, and so it is doubly holy. For to the Hindu, the soil of Hindustan is only less sacred than its rivers, of which Mother Ganga, the Ganges, stands first; and the hills are sacred too, for they are the birthplace of the rivers, and the high snows are the homes of the gods. So Hardwár, which is the gateway of Hindustan, and the threshold of the hills, is the marriage-place of that remote wild holiness that dwells in peak and glacier and forest, and of the warm and comfortable godlings of the plains, who bless the plough and the firestone, the hearth and the bed, and give the water that means life.

It is by Hardwár that the Hindu starts upon the most arduous of his pilgrimages, to the many sources of the Ganges; and all the way his feet are set on sacred ground. For the hillman invests all his surroundings with some of the attributes of the gods. By an instinct that is surely older than any formulated religion a peak is often named for a goddess, while on the highest point of a day’s march, on the summit of an isolated hill, or on any bold outpost thrown out as an eyrie above the gulf, stands a little shrine of stone, or a flutter of votive rags tied to a thorn bush. Inside the shrine is perhaps a wooden doll called by the name of a god of the Hindu pantheon, but the place was holy before the gods were named. For in the hills man is paradoxically struggling with nature, yet grateful for every favour wrung from the harshness that surrounds him, and always in the presence of a vastness he may love or fear but cannot hate. He is at strife with the power he worships, and he must give thanks for his life, for his food and for his rest. So when he comes to these high places he stands for a moment and awaits a blessing and he leaves his thanks for a sign.

Though it stands at the foot of the mountains, Hardwár does not belong altogether to the plains. The last outposts of the Himalayas are little pointed hills that guard the sacred place on either side. To the North is the great gash where the river splits the forest-clad foothills. They rise three thousand feet in a dark swoop of foliage and the summit breaks in a line of tawny cliffs. Behind is another range twice as high, of bare shoulders and pine-clad slopes, too far for any detail to be seen; and beyond are the high snows.

The streets of the holy town are steep and twisted; they are paved with cobbles like the by-ways of a country town in Yorkshire. They are full of people of every kind, for this is not only a place of pilgrimage but a trade outlet for the hill tracts of Tehri and Garhwál, and it is near the borders of the Punjáb. Where there is a shifting population of pilgrims it is easy for a criminal to hide himself, and Hardwár is a famous centre for the traffic in women. ‘A bride from the East and a groom from the West’ runs the proverb, but since the ordinary folk never arrange a marriage far afield, there is no legal means by which the surplus women of Oudh can go to the surplus men of the Punjáb. There are heavy penalties, but it does sometimes happen that a woman is kidnapped from the parts where she is an incubus and taken to the West where she has a market value. ‘I will sell you into the Punjáb’ a father threatens his disobedient daughter. And if a woman is travelling unwillingly, what could be more convenient than to take her in purdah in a closed palanquin to wash away her sins at Hardwár, and there hand her over to one of the Punjábis of whom the place is full?

Sometimes, too, a hill-girl disappears and a rich man in the plains acquires a wife of rare beauty --- once she is washed, for it is too cold to wash much in the hills. And nowhere could be more suitable than Hardwár for the transfer, for there is nowhere else where the hills and the plains jostle each other so closely, where meeting is so easy and where questions are so few.

Wickedness clings to the skirt of holiness, for what is holy becomes lost in superstition, and at once those arise who are eager to make a profit. There are charlatans among the priests, there are evil eyed fakirs, and there is every kind of impostor among the hundreds of beggars. And it is because the place is holy and blessed by nature that it is also the home of pimps and panders, smugglers of the intoxicating hemp drugs, vendors of cocaine, cattle-thieves, kidnappers and gamblers. That was why Gopál had brought Sáhib Singh to Hardwár; in an atmosphere so exciting and so strange to all the old man was used to in his home, he could most easily be brought to do Gopál’s will.

It was still early when they left the station, and the snows were poised in a silver perfection more delicate than the mists of noon or the shell-pink of evening. There was a cold and stony light in the cobbled streets, some reflection of that bridal of stone and running water which is strange to the man of the plains, used only to dust and baked mud and stagnant ponds of water weed, and this clarity in the air helped to fill Sáhib Singh with the feeling of holiday and adventure.

As they wound through the narrow bazaar Gopál had difficulty in getting the old man along. He wanted to stop at every shop and buy clay images of the gods, necklaces for his daughters, bottles of Ganges water, or tiny models of the temples; but it was not part of Gopál’s game that any money should be wasted on rubbish of that kind and he earned the dislike of many eager shopkeepers by his firm hold on his father-in-law’s elbow. They came at last to a narrow gate of stone into a paved courtyard, in the centre of which rose a square pyramid of steps leading to the house where a black bull of polished basalt knelt in adoration before the god who became flesh in the bull’s own form.

When they had done what is prescribed they went to the steps leading down to that pool of the Ganges which of all the holy rivers is most holy. This is the famous Har-Ki-Pairi, the steps of heaven, where the ashes of the most pious of the Hindus are returned to the gods. The wide shallow steps form an angle, against which the water flows, and a bridge crosses to a long pier built in mid-stream so that the pilgrims can bathe on both sides of the pool. The near bank is lined with many-storied palaces, where the Princes of India live when they come to wash away their sins, but the other bank, far away, is only a low line of sand and trees. Here in the pool great fish fight for the food the pilgrims throw them. When a man throws in bread, the water seems alive with dark lashing bodies, three or four feet long, while shadowy forms glide round the fighting tangle, silent and evil. Since the ashes of so many great ones are poured into the pool, there is sometimes to be found on the bottom the fused gold of a ring or a gem that was too hard for the fire, and there are men who stand all day waist-deep in water thoughtfully feeling with their toes among the fragments of calcined bone and the heavier ash, for a find that might mean a pension for life.

Standing on the pier in mid-stream, you are at the very heart of Hardwár. Stone is married to running water, emitting a freshness that is as much scent as sight, and from the wide expanse of glittering river, the sky itself seems to take an added light. There is light everywhere; it is a bath of light, which seems in its liquid diffusion to penetrate and soak through matter, so that even the under side of the bridge is patterned with shifting silver. When the sun is hidden in cloud there is a peculiar cold brightness like the brightness that fills a room after a fall of snow, and at all times there is a feeling of space, of limitless extension in every direction, that disregards both the buildings and the towering hills.

When they had bathed and fed the fishes, which delighted and fascinated Sáhib Singh, they went to the dharm-shála where they were to spend the night. A dharm-shála is something between an hotel, an almshouse and a monastery. It is built as an act of charity by a rich man who is afraid his account with God is written in red like an overdraft in a pass-book; and the manager or warden is to some extent a cleric; there is a faint smack of sanctity about him. Unless they are destitute, visitors are given only accommodation; they buy their own food and cook it themselves, and if they are men of means they are expected to contribute something to the upkeep of the building. The dharm-shála Gopál chose was built about a large square court in the form of a narrow two-storied cloister, but the cloister was divided into cubicles or stalls, one behind each arch. The rooms on the lower floor were about ten feet square, with one open wall giving to the yard. Above, they were not so deep because a passage ran along the front to give access to them. A building that might have been pleasant to the eye, though simple, was spoilt by the grass mats and screens which had been hung in front of many of the arches by pilgrims who had brought wives and children. By the pillar between every arch was a little blackened hearth, for two bricks will make a fireplace in India, and from most of them rose a wisp of blue smoke. The air was full of the sharp scent of wood smoke and burning cow-dung, and the warm rich scent of cattle, for many of the guests were villagers from nearby who had come in the ox-drawn carts which take their families to fairs and weddings, their grain to the threshing-floor and their sugar-cane to the press.

There were many others besides villagers from the neighbour-hood. Tall Játs from Delhi and Agra and the Punjáb; sly little Mahrattas in turbans strange to Northern eyes; sleek Mewári banias come to atone for a life of profit and loss --- but not much loss; respectable Bengalis with slippers, spectacles and umbrellas; and hillmen of many kinds --- Garhwális, crinkled about the eyes from gazing at the snows, Kumáonis, and Dogras clad in shapeless coats and trousers made from home-spun woollen blanket, and here and there the boyish Mongolian face of a Nepáli or the slant eyes and red cheeks of Tibetans, with long hair like a medieval page, and a wealth of strange gear - brass-bound instruments for mixing tea and butter, hooped cradles and copper-studded guitars set with turquoise.

Gopál Singh did not waste very much time over settling down for the night. He had not come here to spend his time in a dharm-shála. When the old man had eaten and had taken a handful of cardamom-seeds and some pán, Gopál suggested that they should go out and see the life of the city. It was dark now, and the shops in the bazaar were even more enticing than they had been by day. There were smoking paraffin flares, guttering over the goods spread out to catch the eye, and often the craftsman himself sat at his work behind the goods. There was a whole street of silver workers, hammering with delicate tools over tiny furnaces of baked clay; sweetmeat sellers behind pyramids of sticky gold, and piles of almond balls delicately browned and dusted with meal; shops clamorous with brass from Benares and Moradabad, and shops where sáris of cloth-of-gold were spread by the side of kingly purple, dark as blood; silver, palest blue, and apple green; scarlet, black, and flame-colour. The cloth-merchants spread out the bales, but Gopál did not stop to buy a flame-coloured dress for Pyárí. He hurried on through the murky garish streets, but with as much consideration for Sáhib Singh as he could manage. He did not pluck at his sleeve so impatiently now, for he wanted him to be happy and complaisant.

At last they reached their destination. It was a kind of bar, which aimed at a richer class of clientele than the ordinary grog shop; but though it was licensed, the two Thákurs were admitted only after a good deal of whispered conversation, for gambling was against the law, though drinking was not. Gambling is not a vice of the Hindu upper classes unless they have learnt it from Europeans; and any of Sáhib Singh’s friends would have scorned to play the games with dice on which grooms will throw away a month’s pay or hill coolies the earnings of a season. There were unshaded electric lights, and the walls, distempered an ugly blue-green, were decorated with tinselled pictures of Hindu gods with blue faces in red and yellow clothes. Hanuman’s tail curved proudly over his monkey-mask, and Krishna piped to his milkmaids, but no one took any notice. Four or five young men in neat white cotton jodhpurs and coats cut in the English style were smoking cigarettes and playing a card game on which they betted heavily, with a great deal of shouting and peals of screaming falsetto laughter; and several more of the same type were watching and drinking.

Sáhib Singh had never been in such a place in his life before, and to his simple mind it was a scene of the wildest dissipation. But Gopál had calculated well; all the novelties of the day had upset his moral balance, and he was ready for new experiences. He tried to pretend he took it all as a matter of course.

This was so grand a place and so much in the European style that there were chairs, and, what was more, you could buy whisky as well as the country spirit which is made from sugar, a kind of rum without much body, but very heady and exciting. Sáhib Singh hardly ever touched liquor, tho’ of course he knew the country spirit, and he had never tasted whisky. Gopál wisely avoided whisky and gave him a glass of the rum. He brought him to the table where play was going on and introduced him to someone he knew. He was most considerate and polite. He explained the game and after a little he made a small bet himself. He went on betting, in very small amounts that would not shock the old man too much; he kept talking about the game, but as he talked and as the rum went down, he contrived to suggest in a way that would have been irritating if it had not been so deferential, that of course a simple old countryman would never dream of betting. Sáhib Singh became more and more intrigued, until at last he was really eager to bet, but he was too shy to suggest it himself.

After a few minutes:

‘Care to share this bet with me? Oh, no, of course, you wouldn’t.’

The old man’s face fell. Gopál won. Sáhib Singh was bitterly disappointed.

‘Well, why not? Share this with me!’

Of course he did, and he was so immersed in the game that he never noticed when his glass was filled. It was filled more than once, and when at last Gopál Singh took him away he was in just the condition his son-in-law desired. Gopál had had no intention of fleecing him in the gambling-den; he had only meant to lead him on till he was too much interested in other things, in the loud laughter and the shouting and the fellowship, to notice how drunk he was getting.

And he was not dead drunk? Gopál was too wise for that. He was extremely cheerful; he was ready to find the most ordinary things uproariously funny, and he was convinced that everyone was as full of goodwill as he was himself. What nonsense old people talked about these educated young men! They were charming, friendly, full of courtesy for an old man who was ready to share their amusements, excellent fellows all of them. And what an excellent fellow he was himself! Not many men of his age could spend the evening like that and enter into all the fun that was going. Old Kalyán Singh could never have done it; he wasn’t man enough and it was really quite surprising that he should have begotten such a pleasant young dog as Gopál.

To all this self-flattery Gopál added as much, and then with a little thrill of excitement he introduced the crucial question of his brother-in-law, Bitiya’s husband.

That Bhola Náth Singh’, he said. ‘He’s not a cheerful man. He couldn’t have made all those young fellows laugh like you did.’

No, no, of course not. Sáhib Singh laughed loud at the idea. Bhola Náth Singh was so small and prim! Not a fine roystering fellow who could spend the night drinking and gambling!

‘And I don't think the tenants like him as much as they like you.’ Of course they didn’t.

‘They have absolutely no respect for him. Now you, you frighten them.’

Yes, he did, it was true; it was only his wife who said he was too soft with them. He was really a tiger!

‘I expect he knows they don’t respect him. I expect he’s afraid you’ll find him out. He’s sure to be frightened of you.’

Of course he was!

‘I’m sometimes a little afraid --- I’m not sure if I ought to mention it. . . .’

‘Of course, come on! Out with it!’

‘Well, I’m sometimes afraid he might play a trick on you and get you to do something that would tie you to leaving the land to him. You see he would never think for a moment of your good name and your family’s and it would be rather a come-down if Galthána, that’s been in your family so long, went from a man like you, with a fine presence, who’s been so much the leader of the neighbourhood, to a man like Bhola Náth Singh --- so small and melancholy!’

It would, it would. Sáhib Singh had never really drought of it before. ‘And I might easily be tricked,’ he said, ‘for I’m a generous, confiding man. I’ve always been trustful and loving and it’s a shame I should be wronged in my old age.’ He began to cry.

This was splendid.

‘It’s all right, Thákur Sáhib. Cheer up. Don’t cry. I’ve thought of a way of saving you from this trickster.’

‘No, no, no. I can’t be saved, I can’t, I can’t.’

‘But listen, Thákur Sáhib; do listen. I’m sure if you try you can think of a way; you’re so clever. Remember how you made those young men laugh this evening --- people who’ve been to Universities and been all over India. You’re not going to be tricked by a fellow like Bhola Náth. He couldn’t have made them laugh!’

‘No, he couldn’t, could he?’ He sat up, suddenly pleased. ‘What shall I do?’

‘Well, Pyárí would look after the land well. She’s a fine girl --- everyone admires her. She always gets her way. Just like you she is!’

Yes, yes, there was something in that.

‘Then don’t you think you should leave it to Pyárí now --- in my name of course --- and be safe from Bhola Náth’ And of course Pyárí would always see that Bitiya was properly,looked after.’

‘Yes, yes, well perhaps. We’ll see. We’ll see later.’ The old man was getting sleepy.

‘But why not do it now? To be quite safe?

‘Can’t do it now. Can’t do it now. Nothing to write with. And the Tehsildar isn’t here.’

‘We don’t want the Tehsildar. And look, here’s an agreement I’ve drawn up all ready. There’s just a little provision in it about an allowance for Pyárí at once — just to show you’re doing it because you love her and you’re not afraid of Bhola Náth. There, you’ve only to sign there. Sit down. Here’s a desk.’

They had got to the dharm-shála now.

‘Oh, all right, all right, but it’s no good without the Tehsildar. No good. No good at all.’ Two minutes later he was asleep.

Sáhib Singh had never been much of a hand at writing; even when he was sober his writing looked as though he were drunk, and it was not very different to-night.

Two young men whom Gopál had known at Agra had come from the gambling-den to witness the signature. Gopál asked them particularly to note that he had carefully explained the contents of the document and brought no compulsion to bear on the old man, who had discussed it rationally. They did note it and then they went away to bed.

Next morning Sáhib Singh was bitterly ashamed. He felt very ill, of course, for he was quite unused to spirits, but far worse was his feeling of degradation. To a country-bred Indian of the highest castes, drunkenness is a shocking vice, the kind of behaviour one only expects in sweepers, Christians and hill coolies. ‘He drinks spirits’, they will say of a man in final condemnation. And gambling too. Like a Musulman or a groom. It was disgusting. Nothing of the sort had ever happened to him before, and it never, should again. He had been a decent god-fearing man all his days, and he would go back to his simple country life and never leave it. He felt all the dislike of which his nature was capable for Gopál Singh, partly because he knew he had been tricked and partly because Gopál was the only person from his other life who had seen him in that horrible condition. He showed his dislike by sulkiness; but towards evening when he felt a little better, he asked if he might see what he had signed.

Gopál showed him a copy, having wisely sent the original by registered post to Anantpúr. Sáhib Singh read it with a sinking heart. In the agreement he was made to say that he was feeling old, and being no longer able to enjoy the pleasures of life as he had in his youth, he had decided to provide for the happiness of his beloved daughter, while he could still watch her enjoyment. He was to give Pyárí and Gopál three hundred rupees a month as an allowance for the rest of his life; and because of the especial trust and confidence he placed in his son-in-law they were to have all his land when he died. It was worse than he had feared, for three hundred rupees was half his income even in the best years, and in bad times, when rents would not come in but land revenue must go out, he would never be able to meet it and to keep up the house at Galthána.

All the pleasure had gone out of his visit. He went about with a leaden feeling in his belly and a sense of something dreadful to come. Yet though he could not enjoy the freshness of the hill air that blew down from the gap in the lulls, nor the holiday atmosphere of the town, he could not bring himself to go home, because he was more frightened of what his wife would say than of anything he might be made to do. He would far rather pay the money quietly all his life than face the Thákuráni’s anger. Nor was Gopál very anxious for that meeting. He thought of going straight back to Anantpúr, and sending a servant to fetch Pyárí, but he knew that that would never do, because then they would never pay him anything and he would get no benefit from the precious document Kalyán Singh was keeping so carefully at home. He must make up his mind to face it, and so at last he did, and the two climbed into the train in sulky silence.

The old man knew it would be better to tell his wife before Gopál did, but though he tried once or twice he could never do it. He had always a kind of thickness and hesitation in his speech, and when he was nervous this became a stutter. As the Thákuráni never stopped talking herself except when she was asleep, he never really had time to get under way, and so at last he gave up the attempt and left it to Gopál. Gopál also waited nervously, but when after a whole day had passed the storm failed to break he guessed the reason and decided he must speak himself. He chose a time when Sáhib Singh and Pyárí were both there, and said to the Thákuráni, in a voice he meant to be casual, but which succeeded only in being noisy:

‘The Thákur Sáhib has been very kind. He has promised to give Pyárí an allowance --- and to leave her the land.’

The last came out with a jerk.

The old lady sat up.

‘How much?’

‘Oh --- well --- well --- three hundred rupees a month.’

‘Three hundred rupees a month! You must both be mad. As if I would take any notice of nonsense of that sort! Why, we should have nothing left to live on. Are you trying to swindle your parents in their old age? Promised indeed! A pretty sort of promise! What does he mean by making promises of that kind without consulting me! Promised indeed! I’ll soon put an end to that.’

She had hardly begun, but Gopál seized a moment’s drawing of breath to say sulkily:

‘It’s a written agreement. Signed and witnessed and stamped. And sent to the Registrar to be registered.’

The silence that followed was so astonishing that Sáhib Singh thought his wife must be ill, and he was just going to risk his life by stepping forward to comfort her when she said:

‘I have something to see to.’

And before they knew what had happened she was out of the room, and they heard her in the courtyard calling for Rám Kallán Singh, her invariable associate, the big Rájput, who of all the hangers-on about the house was the most permanent and the most reliable. What she told Rám Kallán they did not know till later.

Sáhib Singh vaguely followed her out, and left Pyárí and Gopál Singh alone. Pyárí turned on him with all the fury that Sáhib Singh had expected from her mother.

‘What have you been doing? What have you done to the old man? What wickedness have you been at?’

‘I can’t answer all those questions at once,’ he grumbled, sulkier and sulkier.

‘Will you tell me what you have done to my father?’

‘It was all for your sake, Pyárí,’ he began.

‘Don’t tell me lies! Will you tell me the truth?’

She stamped with such exasperated rage and crouched so like a wild cat over its kill that he thought she would spring at him as she had done once before. She had scratched his face and torn off his turban and he had been afraid for his eyes. But he was not physically afraid of anything she might do; it was the flame in her spirit that daunted him when she was like this. He told her something so like the truth that she was easily able to guess what had really happened.

She flung herself on the ground and sobbed:

‘That I should be married to a wicked man! Wicked and ungrateful! My poor old father!’

Gopál felt wronged and aggrieved and went upstairs to the bedroom. The moment he stepped into it Rám Kallán, who had been hiding in the shadows, snapped home the padlock on the outside.

‘You’ll stay there, my beauty, and you’ll starve!’ he said.

The Thákuráni was indeed a notable woman. She had seen at once that her strongest card was possession of Gopál Singh’s body, and she had gone straight to Rám Kallán with orders that Gopál was not to leave the house and was to be locked up as soon as possible, whether by guile or force. Rám Kallán grinned with delight. His usual occupation was to sit in the yard and order the carters about, but he sometimes went out with a large stick and two assistants to see that the rent came in a little quicker, or to convert someone to a more proper respect for the house of Sáhib Singh. He hated work and he loved a row --- as long as he was winning. And he was too clever to have much experience of a row when he was not. He adored the Thákuráni Sáhiba, who provided him with rows as a mistress provides a dog with walks and bones; and there had never been a wag in his tail for Gopál.

When she had made this arrangement the Thákuráni looked for her husband.

To his great surprise she spoke to him quietly and with an affectionate contempt.

‘Now, you silly old man, what have you been doing? Tell me all about it.’

When she had heard it all, Rám Kallán came and made his report, and she at once sent him to Sháhábád to fetch her cousin who had been to England and was a barrister-at-law. Until he came no one went near Gopál and he had nothing to eat.

The barrister told them that the agreement could not have been registered, because both parties would have had to go before the Registrar and verify their signatures, which Sáhib Singh had not done. This, he said, would tell against the document in court, because the only reason there could be for not registering it was that Sáhib Singh did not want to, which would bear out his story. In short, he thought they would probably be successful in contesting the agreement, but it would cost money, and the Anantpúr people had a longer purse. Everyone was agreed, however, that it must not go to court if it could possibly be avoided, for Sáhib Singh’s only answer would be the truth, which would involve admitting that he had been drunk and would disgrace him in the eyes of all decent Thákurs. That was the cunning of it. And Gopál had probably reckoned that sooner than contest the agreement in court they would be willing to enter into a new agreement, registered before a Registrar and therefore legally binding, for a smaller allowance. The barrister also felt bound to point out that Gopál Singh could bring a perfectly true criminal charge against them for locking him up.

‘Oh, no he couldn’t,’ said the Thákuráni with decision. ‘We should all swear black and blue it never happened and so would everyone else in Galthána. I would bring a thousand witnesses into court if it was necessary.’

The barrister smiled, conceded the point, and went home with a basket of eggs and butter and vegetables.

The Thákuráni decided that she would not be bluffed. They would not pay a penny, and Sáhib Singh should at once make another will which should be properly registered and stamped. Meanwhile, Gopál was to have nothing to eat till he produced the document.

‘But I haven’t got it,’ he objected through the door. ‘My father has.’

‘You can easily write something that will make your father send it, and Rám Kallán shall take the message and bring it back. And the moment you write the message you shall have your food, but not be let out till it comes,’ the old lady explained.

‘Well, I won’t.’ He relapsed into sulkiness.

An Indian can do without food more easily than an Englishman and Gopál was not seriously inconvenienced till the second day. But Pyárí was torn by divided loyalties. This was the only mistake the Thákuráni made; she forgot that she herself did not really belong to the Galthána household, or that if she did, by the same logic Pyárí belonged to Anantpúr. It never occurred to her that Pyárí could be on any side but hers.

And indeed, all Pyárí’s reason was on her mother’s side. Galthána, as a place, as a house and as a family, she loved, while she had as yet no feeling for Anantpúr; though she often quarrelled with her mother, she was fond of both her parents, and she detested what Gopál had done. But she could not forget her husband. All her life she had been taught that she would have a husband she must worship, to whom she owed obedience as her duty before all things, and added to that was her love for him as a man. She would gladly have stabbed him when she heard what he had done, but she would gladly stab herself for him now that he was hungry and alone.

She ran up to his room the third night and opened the door, brought him food and put their things together. They slipped out of the village while it was still dark and stopped the first bus that ran into Sháhábád.